Service bulletins

AT LARGE

SCOOP UP A DOUBLE HANDFUL OF MOtorcycle service guys. Lock them in a restaurant and promise to buy them dinner—on one condition: that they answer as best they can all the questions you can throw at them about their world and their work.

I don’t know what you would ask them, but when I collected 10 such guys, I asked about machine complexity, their own training and general competence, what the manufacturers doing right and wrong, what the dealers are doing ditto, how they feel we (the bozos who break the things they fix) are doing, and on and on, into a very long night.

It happened in August in Monterey, California, and the guys I asked to sing for their dinners were from three Monterey Peninsula bike shops. From Honda/Kawasaki/BMW of Monterey came William Smith, bossman, Dan Kyle, service manager, and technicians AÍ Jesse and Charley Schaefer. Salinas Cycle Center (Suzuki-Kawasaki) sent dealer principal Steve Schaub, service manager Greg Bebee and tech Rob Bothwell. And from Gilroy Motorcycle Center came Clark Winn as chief, Stan Mcbee as service manager and Jim Knappen as the combination parts/service guy.

These were not reluctant speakers. These were guys with a lot to say. Such as:

—On the complexity of today’s bikes. Yeah, things were simpler back in the Sixties. But nobody felt unable to meet the challenge of the new hardware. They didn’t resent the technology; they did resent the styling that made the hardware hard to get to. Case in point, agreed by all as typical: the crashed bike that seems like a write-off but is all cosmetic damage. Underneath the mess is a fully operational motor and cycle. Verdict of the service gang: too much flash. Advice to manufacturers: cut the styling budget.

—On their own competence. Touchy subject. Nobody felt that their training ranked with the Ivy League, and especially didn't like paying for their training themselves. Problems appeared to lie in the area of curricula; one guy trained to fix several marques said he had run into the same course three times, first at his basic motorcycle trade school, then at Brand X and again at Brand Y. Verdict of the gang: They were offered too little training, and what was there was too costly and too shallow. Advice to manufacturers: Get serious about training, support the dealer and consumer by paying for the techs to attend the schools.

—On why service costs so much today. Lots of theories. One was thought to be the manufacturers trying to cut warranty claims by insisting on sometimes possibly redundant or unnecessary work; another was the almost unbelievable parts proliferation. Rhetorical question raised by the gang but not answered: Why does every Japanese bike need a completely different voltage regulator? Customers wonder why a handful of minor tune-up parts costs so much, said one tech, and so does he, when his VW Rabbit’s equivalent parts cost considerably less. Still, everybody agreed that whatever the service charges, nobody in the service bay was getting rich.

—On what the manufacturers ought to be doing. Three major items surfaced. First, they should concentrate on building and aggressively selling entry-level bikes. Second, they should be making good on the “lowmaintenance” promise of the technology available today, and should not build supposedly low/no-maintenance systems (such as hydraulic valves) that in practice do require attention. Third, they should not orphan bikes so quickly. Excedrin Headache Number One for this group seemed to be that about the time they get one model-year figured out, the whole range is obsoleted and replaced with all new hardware.

—On what the riders ought to be doing. First, reading their owner’s manuals. Everybody agreed that the manuals were not very good, but also agreed that their problems would be dramatically reduced if every rider actually read his manual. They estimated that only about a quarter of their customers had any knowledge of what lay between the manual’s covers. Second, the buyer should understand that when he buys a complex piece of machinery, it will inevitably require skilled servicing—and that means money out of pocket. Third, riders educating themselves about riding so that fewer crashed bikes come into the dealership. Fourth, wearing helmets. Fifth, in the case of young riders, not succumbing to peer pressure to buy the most horsepower they can squeeze out of a loan officer.

There was a lot more, of course. Any 10 motorcyclists, given the chance to sound off about what’s wrong and right with the sport, will have plenty to say. But what impressed me most about these guys— all of whom had just come from another long, hot day with their SnapOns—was their sheer enthusiasm. They ranged in age from the mid-20s to the late 40s, yet they all exuded a love of the sport. Asked whether they'd stay in the game, good times or bad (and they’d all been through both), they reacted with amazement: of course they would, was the answer. Everything else was just . . . work. To a man, they admitted they were in the business because it allowed them to stay in constant contact with motorcycles.

There's a lot of talk in the plush corporate offices of the major manufacturers right now about the “future of motorcycling.” As far as I’m concerned, as long as you can assemblemore or less randomly—a bunch of guys like these, who work and live right where the factories’ mistakes meet up with our dumb thumbs, and have them be as besotted with motorcycles and motorcycling as they are, the future of the sport looks just fine. High sales, low sales or no sales, it’s people like these who make our sport what it is. —Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialIdol Speculation

December 1987 By Paul Dean -

Leanings

LeaningsDesmo Fever

December 1987 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1987 -

Roundup

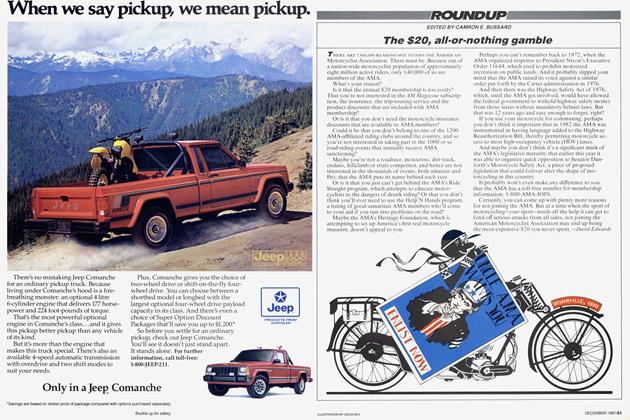

RoundupThe $20, All-Or-Nothing Gamble

December 1987 By David Edwards -

Roundup

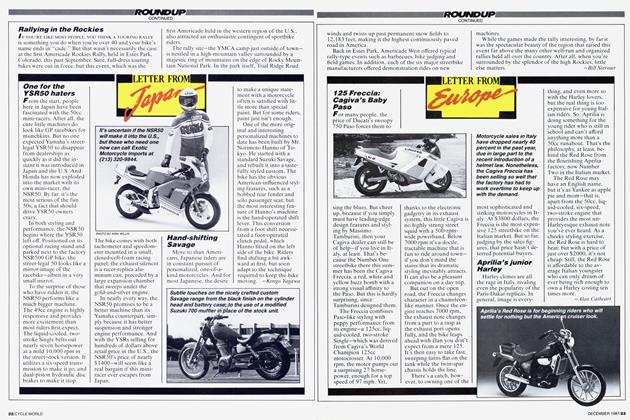

RoundupRallying In the Rockies

December 1987 By Bill Stermer -

Roundup

RoundupOne For the Ysr50 Haters

December 1987