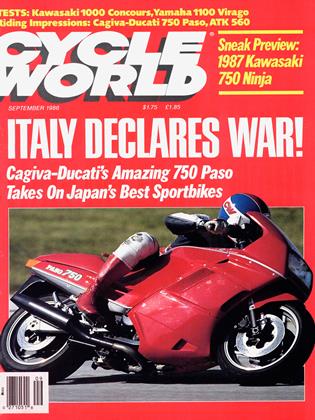

K4WASAKI 1000 CONCOURS

CYCLE WORLD TEST

MORE THAN A NINJA WITH LUGGAGE FOR TWO

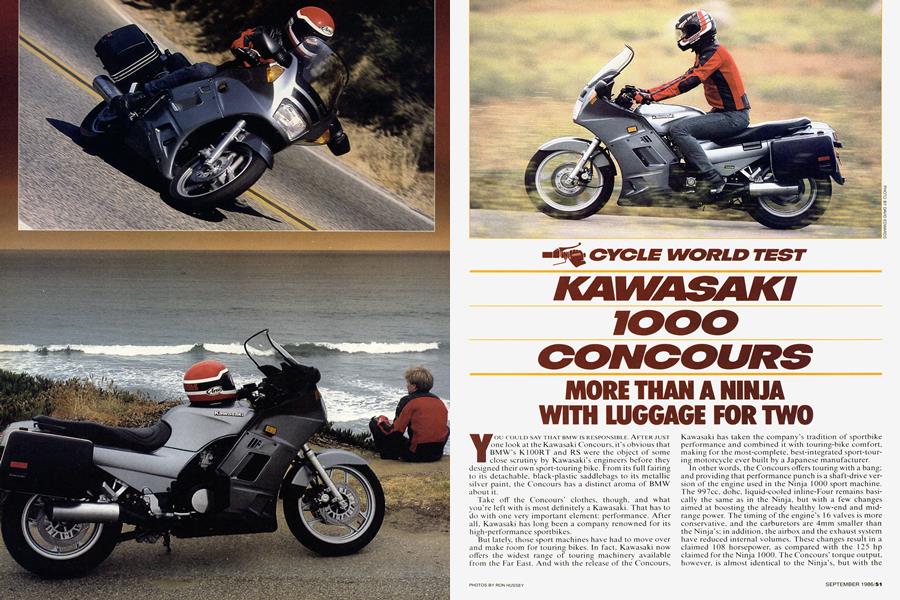

YOU COULD SAY THAT BMW IS RESPONSIBLE. AFTER JUST one look at the Kawasaki Concours, it's obvious that BMW's K100RT and RS were the object of some close scrutiny by Kawasaki's engineers before they designed their own sport-touring bike. From its full fairing to its detachable, black-plastic saddlebags to its metallic silver paint, the Concours has a distinct aroma of BMW about it.

Take off the Concours' clothes, though, and what you're left with is most definitely a Kawasaki. That has to do with one very important element: performance. After all, Kawasaki has long been a company renowned for its high-performance sportbikes.

`i3ui lately, those sport machines have had to move over and make room for touring bikes. In fact, Kawasaki now offers the widest range of touring machinery available from the Far East. And with the release of the Concours, Kawasaki has taken the company's tradition of sportbike performance and combined it with touring-bike comfort, making for the most-complete. best-integrated sport-tour ing motorcycle ever built by a Japanese manufacturer.

nother~vords, the Conc~urs offers touring with a bang; and providing that performance punch is a shaft-drive ver sion of the engine used in the Ninja 1000 sport machine. The 997cc, dohc, liquid-cooled inline-Four remains basi cally the same as in the Ninja, but with a few changes aimed at boosting the already healthy low-end and mid range power. The timing of the engine's 1 6 valves is more conservative, and the carburetors are 4mm smaller than the Ninja's; in addition, the airbox and the exhaust system have reduced internal volumes. These changes result in a claimed 108 horsepower, as compared with the 125 hp claimed for the Ninja 1000. The Concours' torque output, however, is almost identical to the Ninja's, but with the peak located 2000 rpm lower.

That explains why the Concours engine feels stronger than the Ninja’s out in the real world. Unless you let the tach needle fall below 2500 rpm, there is no need to change down a gear or two when you want a quick burst of speed; instead, you merely open the throttle. Even in its rather tall sixth gear, the engine lugs with ease from lower rpm. And in the mid-range, the Concours performs even more impressively. When the throttle is dumped wideopen in the 4000to 8000-rpm range, the power comes on sportbike-hard and builds linearly until flattening out just a little before redline.

Throughout its entire power range, however, the Concours’ engine transmits an often-annoying amount of vibration to the rider and passenger, despite its use of dual gear-driven, internal counterbalancers. On our test bike, we could feel the buzzing through the fuel tank, the footpegs, the handlebar and the seat. These vibrations are more of a tingle, actually, and are at their worst when the engine is revving quickly. The Ninja 1000 we tested back in January didn’t have as much vibration, and other Concours we have ridden seemed to be a bit smoother. Some of that tingliness may be a by-product of the Concours' frame, which uses the engine as a stressed chassis member and so has no rubber-insulated motor mounts. This frame design was lifted from the 900 Ninja rather than from the 1000, although the main frame structure, the swingarm and the bolt-on rear frame section all have been considerably beefed up to handle the additional loads created by this larger motorcycle that has a greater carrying capacity.

And larger the Concours is, despite using the frame from the smaller Ninja. This sport-tourer is tall and wide at the seat, and the fuel tank is one of the widest ever found on a production motorcycle. The tank holds just over 7 gallons of fuel, which, when topped up, positions more than 42 pounds of gasoline high on the bike. You get a graphic sense of the Concours’ size and high center of gravity the first time you have to push it around. The width and height of the seat complicate matters, making it difficult for an averaged-size rider to plant both feet on the ground simultaneously when stopped. Even when moving along at low speed, the bike’s size can be intimidating.

But out on twisty, two-lane roads, the Concours handles remarkably well in spite of its relatively large size. At seven-tenths cornering speeds, the bike requires only a light touch and a low level of rider-effort to get through tight sections of the road gracefully and quickly, feeling more like a chubby Ninja than a massive touring rig. It doesn't squirm or wander off-line when pushed hard through corners, and when braked in mid-turn, the bike has only a mild tendency to sit up and go straight. And until the turns are charged with the kind of gusto associated with sportbikes, the cornering clearance is adequate.

If and when aggressive cornerin'~ does become the order of the day. the Concours' suspension can easily be set up to deal with it. The front fork is air-adjustable. and we found that 11 psi of air allowed it to work competently when cornering hard over a surprising variety of road surfaces. Higher pressures made the front end feel too stiff for most reasonable situations, and lower pressures sacrificed ground clearance.

Likewise, the single rear shock is air-adjustable. but it also features four rebound-damping adjustments. With 28 psi of air and the damping set on the Number 3 position, the rear shock matched the fork in terms of ride and ver satility. After setting both ends, we seldom found a need to change either end.

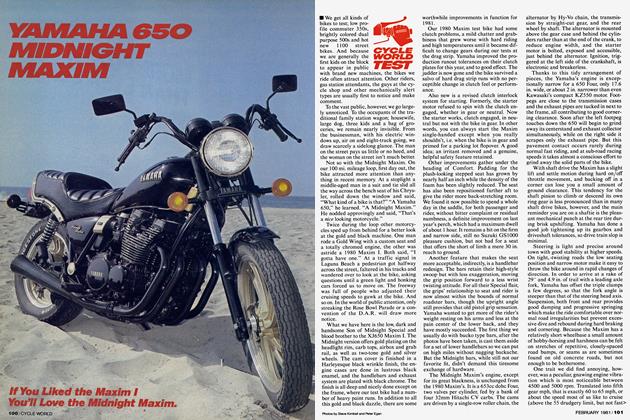

There’s also a lot of versatility built into the Concours' overall seating position, which generally provides an excellent level of comfort. The rider has plenty of room, even though the seat/peg/handlebar layout is biased toward the sporting end of the spectrum rather than being the usual bolt-upright touring position. There’s a slight step in the wide, firm saddle, but it doesn’t prevent the rider from moving back when he wants an alternative place to sit. In fact, about our only complaint about the ergonomics had to do with the individual, forged-aluminum handlebars; most of our riders felt that the bars would be more comfortable if they had a slightly higher rise.

The problem of the lowish handlebars is magnified by the fact that the w indscreen does its job nicely and protects the rider from the wind; and without a blast of air hitting his chest, the rider must support all of his upper-torso weight with his hands and foremarms. Furthermore, the windshield directs the wind across the top of the rider’s head in a way that causes a deafening, crackling sound inside his helmet. At higher speeds, the sound is accompanied by buffeting.

Aside from those two upper-body problems, though, the fairing offers good protection from the elements, shielding the rider from the ankles to the head. The various scoops and vents built into or onto the fairing do a nice job of keeping cool air circulating around the engine so that the rider is not baked on hot days. As long as the bike is moving, the rider feels very little engine heat whatsoever.

Rounding out the Concours’ sport-touring makeup are its two large, removable saddlebags. The mounting system for the bags is typical in that it’s simple and allows almost instantaneous bag removal. But a unique feature of this system is that the mounting brackets detach with the removal of two bolts, and color-matched body panels snap in place, giving the rear section of the motorcycle a clean, finished appearance when the bags are left off. But. as with so many detachable saddlebag systems, the Concours is an extremely wide motorcycle (two inches wider than a Gold Wing) when the bags are mounted, yet various cutouts and indentations inside the bags (to accommodate the mounting hardware) seriously detract from their usable volume.

Nevertheless, all of this adds up to a motorcycle that was meant to be ridden quite quickly and comfortably over relatively long distances. And make no mistake—the Concours is fast. No other touring bike of any kind will keep it in sight for long, and only a BMW K100RT or RS will even stay close to it. And on backroads, the Concours is less tiring on its rider than a K-bike simply because it doesn't have the bothersome front-end dive and shaftdrive reaction of the BMW. But the Concours is similar to the Beemer in that it finds cruising in the fast lane preferable to putting along all day at 55 mph. For that reason, using the Concours as an interstate tourer would be a misappropriation of the bike’s talents, for it doesn't begin to show its mettle until the road turns serpentine and the speeds approach triple-digit figures.

Still, as an interstate-style touring rig, the Concours can perform quite competently; and as a sport-touring bike, it's superior in practically every way to anything on the market. Not only that, the Concours is set apart from other current sport-touring bikes because of its pure-sport bloodlines.

When building the bike, Kawasaki never forgot that fact. When riding it. neither w ill you. 0

KAWASAKI 1000 CONCOURS

$5899

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

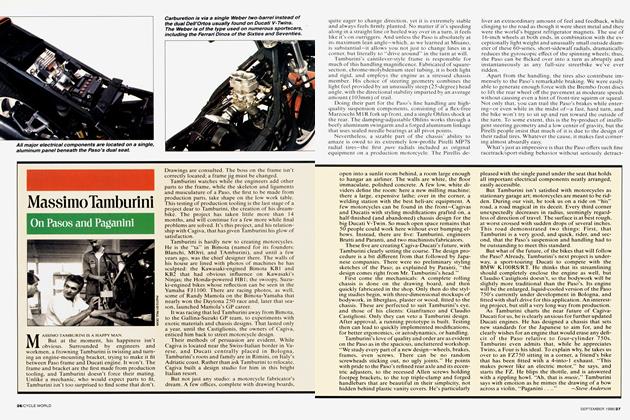

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson