HIGH SIERRA RUBICON ADVENTURE

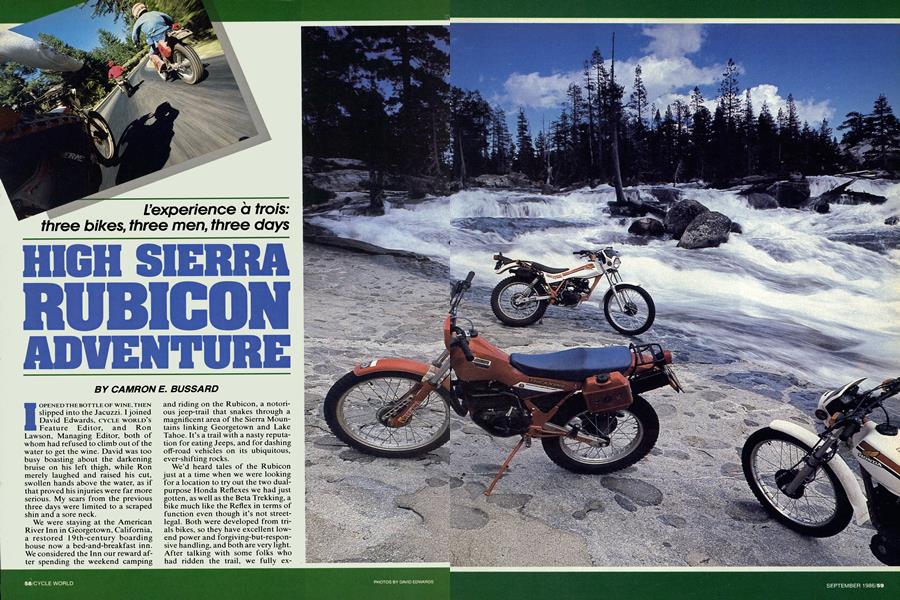

L'experience à trois: three bikes,three men,three days

CAMRON E. BUSSARD

I OPENED THE BOTTLE OF WINE, THEN slipped into the Jacuzzi. I joined David Edwards, CYCLE WORLD'S Feature Editor, and Ron Lawson, Managing Editor, both of whom had refused to climb out of the water to get the wine. David was too busy boasting about the darkening bruise on his left thigh, while Ron merely laughed and raised his cut, swollen hands above the water, as if that proved his injuries were far more serious. My scars from the previous three days were limited to a scraped shin and a sore neck.

We were staying at the American River Inn in Georgetown, California, a restored 19th-century boarding house now a bed-and-breakfast inn. We considered the Inn our reward after spending the weekend camping

and riding on the Rubicon, a notori ous jeep-trail that snakes through a magnificent area of the Sierra Moun tains linking Georgetown and Lake Tahoe. It's a trail with a nasty reputa tion for eating Jeeps, and for dashing off-road vehicles on its ubiquitous, ever-shifting rocks.

We'd he~rd tales of the Rubicon just at a time when we were looking for a location to try out the two dualpurpose Honda Reflexes we had just gotten, as well as the Beta Trekking, a bike much like the Reflex in terms of function even though it's not street legal. Both were developed from tri als bikes, so they have excellent low end power and forgiving-but-respon sive handling, and both are very light. After talking with some folks who had ridden the trail, we fully ex pected the rocky terrain of the Rubicon to be an excellent test for the motorcycles. What we didn’t expect was that the trail would test us as much as it tested the bikes.

Before we began our assault on the Rubicon, I planned a day for us to play around on and get familiar with the bikes. Because the Trekking was virtually unknown to us, we thought it would be a good idea to ride with someone familiar with the machine. So we contacted Scott Head, the current National Trials Champion who won his title on a Beta TR32, the bike that serves as the basis for the Trekking. And because he also happens to live in Placerville, just a few miles from Georgetown, and is familiar with the area, he was a perfect choice.

As we made our way down the first tight, rocky trail on Saturday morning, we were impressed with the Trekking and both Reflexes. They turned out to be decent trailbikes—as long as we stood up. But when we tried to sit down during smooth sections of the trail, the trials-type seating position felt horribly cramped and uncomfortable, especially on the Reflex. The Trekking has a far lessradical seat that has more padding and is longer, but it’s still a feet-high, seat-low bike.

As we were to discover later, about the only way to traverse the rocky Rubicon was by standing on the footpegs, so for our purposes the tiny seats and high pegs were not much of a problem. Of more immediate concern was that our trail suddenly disappeared into a ravine washout, and I thought we would have to turn back. But to a National Trials Champion there is no such thing as turning back. Scott poked around a bit and discovered that a little way up the hill, a tree had fallen across the ravine. It was a 10-foot drop from the tree to the rocks in the bottom of the wash; and when Scott pronounced that we could easily ride across the log over the washout, I knew that the time for fun had ended, and that the time for fear had begun.

As Scott forged a trail through the forest to the fallen tree, I walked out on the decaying log and peered down into the abyss, knowing that one wrong move when riding across would prove disastrous for the bike and painful for its rider. Nonetheless, Scott put his Beta’s front wheel on the tree, opened the throttle and rode to the other side, where he simply jumped his bike off onto the trail. Lawson, not to be outdone, put his Reflex’s front wheel on the log, looked over the edge—and froze. Af-

ter David and I finally pried Ron’s cold, stiff fingers from the handlebar, Scott rode Lawson’s, then David’s, then my bike across.

Things only got worse before we found our way back to the truck. We rode down a dark, mossy creek bed complete with brown slime-covered rocks in an area where it seemed as if vile creatures beneath the surface were attempting to pull us into the slime. We rode nearly a mile in the stream, and the Reflexes proved to be submarines, impervious to water splashings and prolonged dunkings. The Trekking, however, drowned out any time water would gather around the sparkplug cap. By the time we returned to the truck—wet, muddy and tired—it dawned on me that we hadn’t yet experienced the Rubicon, and already we looked like we’d spent the whole day being dragged behind the truck.

For weeks I’d been looking forward to the romance of camping along the trail, of building campfires and telling ghost stories like I had when I was young; but upon reaching the truck, I could convince no one to break out the tents. So we got a room in Placerville. Before Scott left us, we asked him about Placerville’s other name, Hangtown. He told us that the town was called this in honor of the over-enthusiastic townsfolk who, during the gold-rush days, refused to wait for the judge to come into town to conduct court trials. Instead, they felt the most expedient thing was to take anyone of a suspicious or offensive nature and string ’em up. Not wanting to hang around Hangtown too long, we were up early the next morning for the drive to Wentworth Springs, the starting point for our Rubicon trek. We immediately unloaded our gear from the truck and began packing the bikes with tents, sleeping bags, cooking gear, food and clothing. All of us had previous motorcycle-camping experience, but it had been a long time since any of us had strapped tent and sleeping bag to bike.

A short time later we wobbled down the trail, our bikes overloaded and weighted rearward. Five minutes later we stopped to repack everything, a routine repeated several times in the next few miles. None of us, it seemed, could keep our loads from sliding off the bikes on the rocky trail. I finally ignored the Trekking’s tiny luggage rack and strapped the cooking gear to the seat, and my sleeping bag to the front numberplate. David reached a similar solution on his Reflex. Lawson, however, was much more creative. He piled everything—tent, sleeping bag, tennis shoes and jacket—on the Reflex’s seat, and fastened it all down as only an experienced racer can do: with no less than 40 yards of duct tape.

That we had no further load problems is truly remarkable, considering the trail. We’d traveled to the Rubicon with a pretty cavalier attitude; after all, this was supposed to be a jeeptrail, and we were not only on dirt bikes, but on motorcycles descended from championship trials bikes, bikes that had been made for rough, slow rock-climbing. We originally thought we’d cruise to our campsite in an hour, set up camp and play around for the rest of the day. As it turned out, we hadn’t considered the difference between normal miles and Rubicon miles, which are twice as rugged and rocky as any other miles on the planet.

But then, no one goes to the Rubicon because it’s easy. The trail winds its way through the mountains along an active earthquake fault line that molds a terrain as dramatic as it is rugged. The Rubicon’s beauty is not ephemeral like delicate yellow desert flowers, here one day, gone the next; rather, its beauty comes from massive, eternal, dark forgings deep within the earth. The trail wanders for miles under nervous, ragged mountains that ring the valleys, and over huge, white granite mounds that look like gigantic, hand-shaped soup bowls turned upside-down. Then, when you least expect it, the trail folds over into endless miles of polished rocks and jagged boulders ranging from the size of a basketball to the size of a bus. In other places the trail disappears in acres and acres of tortured, chaotic rock.

After four hours and 15 miles on the trail, nearly all of it spent standing up, we decided to camp beside Buck Island Lake, near a spectacular waterfall fed from another lake higher up the mountain. The only catch was that in order to get where we wanted to camp, we had to ride down a sheer granite face, make a sharp turn around a garage-sized boulder, and feel our way through 20 yards of dense ground cover.

We were pleasantly surprised when the bikes proved to be quite easy to ride down, for they got incredible traction on the solid rock. Other than having to deal with the Trekking’s horrible front brake, the only real difficulty was in convincing ourselves that we could actually ride on the rocks, even though we knew the bikes were up to the task. In fact, there was never a situation over the whole trail that the bikes couldn’t negotiate. When the going got tough, we sat down and paddled with our feet, and as long as the throttle was open, the bikes kept going.

After we set up camp, I went fishing. I had been elected supply sergeant for the ride, and had intentionally carried in no meat, simply because I just knew I’d catch a mess of fish and impress Lawson and Edwards with my angling skills and woodsman’s lore. But on the second cast, I snagged my line and broke my rod. Lawson and Edwards immediately began looking like Ethiopian poster children, reminding me that I was responsible for their hunger. Thoughts of the ill-fated Donner party filled my mind, so I suggested that it would be fun to ride the 18 miles into Lake Tahoe, buy some beer and steaks, then ride back in the dark and have a feast. Remarkably, they bought the idea. I found out later, however, that David went along only because he had hopes of enjoying a sumptuous meal and a warm motel in town. In other words, he planned to mutiny.

We were able to make pretty good time on the way to town because the bikes were lighter and handled much better without the camping gear. The Beta has vast amounts of power, but no brakes to speak of, while the Reflexes have pretty good brakes, but not a lot of power; so all in all, the bikes were evenly matched for the race to town. Uphills on the Trekking were a blast, especially one particularly long and nasty hill named Cadillac in honor of an old LaSalle found on it years ago. We could get through the most difficult of sections in second and third gear with the Trekking, while on the Honda we often had to grind up the hill in first. But the Reflex was easier to ride on the rugged downhills because of the compression of its four-stroke engine and its superior brakes.

We had a spectacular ride into Tahoe through some of the most scenic country any human has ever seen. When the glaciers receded at the end of the ice age, they left behind icegreen water that formed the thousands of lakes in the mountains above Tahoe. Pine forests now line the shores, along with occasional patches of white-barked Aspen mirrored in water that looks like the sky turned upside down.

After standing up through 10 miles of rocks, we had to ride about eight miles of paved road. As tired as we were, we got little comfort from sitting on the thinly padded seats; and winds from across Lake Tahoe chilled us through our sweat-soaked garments. But soon, we found ourselves in one of those bright, white, sanitized supermarkets. We were clad in mud-covered dirt-biker’s regalia, and curious people kept asking if we had won the race. We claimed that we tied for first as we gathered enough food to fill our backpacks.

It was dusk before we started the ride back. I can’t say that I’d like to make that ride again in the dark, but it was a rather . . . well, exciting experience. The Reflex’s headlight danced in the darkness like a 55-watt firefly, but the Trekking’s light was so dim I had to stay close behind the Reflexes just to see where I was going. When David stalled on a particularly rocky ledge, I passed him, then stopped in a less-steep section to make sure he made it up. As I turned off the engine and sat in the darkness, I realized for the first time that we were riding on one of the most challenging trails we had ever been on, in the pitch-black. I couldn’t wait to get close to a nice, bright fire.

It was 9 o’clock before we felt our way back down the rock face to our camp. We quickly started a fire, cooked the best steaks of our lives and fell into our tents and sleeping bags. Even the rock-hard ground felt comfortable by then.

The previous night’s adventure notwithstanding, I was up early. And as the sun rose and I watched the shadow of the mountain slip back across the lake, I knew our time on the Rubicon was nearly over. It was chilly as we packed the bikes and began our return trip, riding up and over the steep rocks in the cold, mountain shadows. The dawn air recalled memories of similar crisp, blue, autumn mornings long ago when I was first learning how to ride motorcycles back in the midwest.

But the Rubicon is too demanding, too insistent, leaving no time for bouts of sentimentality or romantic visions of days past. The trail is jealous, and if you fail to give it your undivided attention, it punishes with unexpected hazards.

By the time we reached the truck, I felt like we had been gone for years; and by the time we reached the American River Inn, we were pleased to be among civilized people once again. Or were we? We were, after all, in Georgetown, home of the annual “Thunder Chicken” festival. Once a year, everyone in town arms himself with a toilet plunger and a chicken, and a starting gate is made from mailboxes. When the mailbox doors drop, everybody plunges their chickens out of the boxes. The chicken flying the longest distance on the course wins.

That night, as we soaked in the Jacuzzi, we all were silent for a while, each lost in his own memories of our adventures on the trail. I thought about how well all three motorcycles had dealt with the brutal terrain in spite of being overloaded most of the time. For bikes intended only to be entry-level machines, they had performed remarkably under extreme conditions that could have been imposed only by experienced off-road riders. In more normal circumstances, I reasoned, the Reflex and the Trekking both ought to make offroad riding a piece of cake for relative neophytes. Only when the situation calls for logging much time in their token saddles does either bike come up a bit short.

My contemplation was momentarily interrupted as Ron and David began their litany of injuries. That’s when I climbed out of the Jacuzzi and got the wine, figuring that if I didn’t do it, no one else would. After savoring a glass of that delicious nectar, I sank deeper into the water, knowing I would never forget the difficulty of the Rubicon—but hoping I would never forget its beauty. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

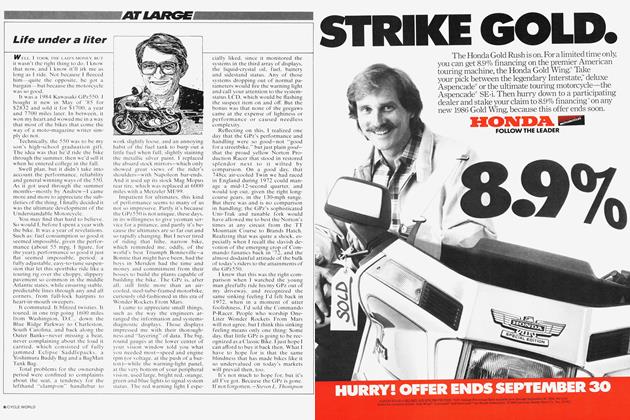

At Large

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

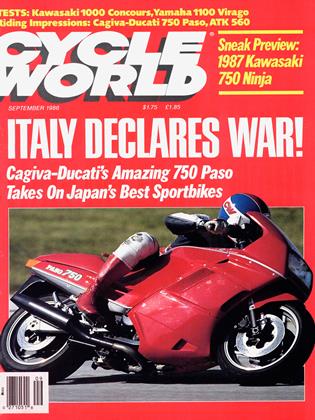

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson