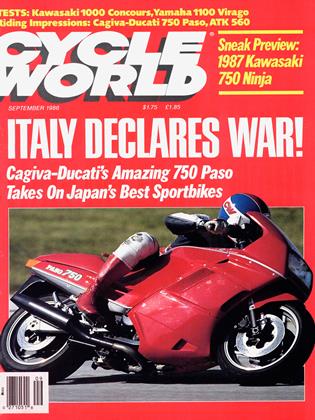

CAGIVA-DUCATI 750 PASO

CYCLE WORLD RIDING IMPRESSION:

From the unlikely marriage of a Duck and an elephant comes one of the world's truly fine sport motorcycles

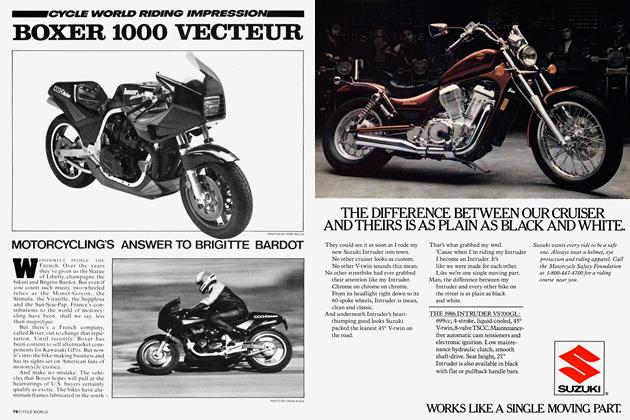

FEW THINGS IN LIFE ARE BETTER THAN A FIRE-ENGINE red Italian sportbike that's right. Sex, maybe, or Häagen-Dazs chocolate chocolate-chip. But not by much. And when an Italian sportbike is as red and as right as Ducati's newest corner-bender, the 750 Paso... well, as the beer commercial says, that's about as good as it gets.

And take our word for it: The Paso is indeed right. We found that out for ourselves by traveling to Italy, where we probed this intriguing machine’s innermost workings, talked to the people responsible for its existence, and became the first journalists anywhere in the world to ride a Paso both on the racetrack and on public roads, racking up more than 500 miles on the very machine you see here. After all that, we can assure you that what you’re looking at is the closest thing to a two-wheeled Ferrari you’re likely to find, a bike that is exciting to look at, thrilling to ride, and just plain fun to be around.

Visually, the Paso’s swoopy, all-enclosing bodywork lavishly coated in positively electric red paint captivates everyone who lays eyes on it. And functionally, it is the most delightful Ducati in eons, combining the tractable power and traditional virtues of Dr. Fabio Taglioni’s beloved V-Twin engine with an ultra-modern chassis that is one of the most magnificent ever to come out of Italy.

In other words, this is not last year’s Ducati dolled up in a new red dress; this Ducati is unlike any other that has gone before it. For one thing, it is the first all-new Ducati produced since the acquisition of that company by Cagiva in 1984. So officially, it is the Cagiva-Ducati 750 Paso. What’s more, the only part of the Paso that has been

designed and developed at the Ducati factory in Bologna is the 750cc engine, which is essentially an upsized and re fined version of the desmodromic-valve, 90-degree V Twin that first saw the light of day in the 500 Pantah back in 1979. The entire remainder of the Paso is the brainchild of Massimo Tamburini and his design team stationed in Rimini, about an hour down the road from Bologna. Chief of design for Cagiva since 1984, Tamburini formerly wasa partner in Bimota, the exotic-bike builders also located in Rimini. So if you think you detect a slight aroma of Bimota wafting through the Paso's chassis, you're probably right.

That may come as a surprise to you, but not to Gianfranco and Claudio Castiglioni, owners of the evergrowing Cagiva empire. Early last year, the brothers Castiglioni charged Tamburini with the design of an entirely new Ducati sportbike, giving him free reign to do whatever he so desired with everything except the V-Twin engine. He responded by designing precisely the sort of machine he’d build for his own enjoyment, even naming it in memory of his longtime friend, the late Renzo “Paso” (pronounced PAW-so) Pasolini, the GP roadrace star killed in a racing accident in 1973. Tamburini loaded his “dreambike,” as he affectionately calls it, with the cost-isno-object stuff of which a motorcycle designer’s fantasies are made: gorgeous aluminum forgings, the highest-quality hardware, and some of the most beautifully machined and flawlessly crafted componentry one could imagine. In fact, the Paso has such a custom-built flavor that some insiders are already calling it a “production-line Bimota.”

Still, for many people, the most memorable aspect of the Paso is its stunning, ultra-modern appearance. When Tamburini was designing the sleek, deeply sculptured bodywork that fully encloses the engine and frame, his main objective was styling; but, since future plans call for the Paso to be liquid-cooled, heat control also was in the back of his mind. And as we found, the full bodywork does a superb job of diverting engine heat away from the rider.

But that pretty much tells the story of the Paso. It’s not just another pretty face; it’s a wonderfully functional motorcycle that flat works. After a full day on the Misano race circuit and another day playing in the rugged mountains to the east of Rimini, we came away thoroughly enchanted with what Tamburini has crafted.

We were most impressed with the handling, which was so crisp, so precise, so confidence-inspiring that we found ourselves charging corners downright aggressively within a few minutes of saddling up the bike for the very first time. The Paso reacts immediately to the rider’s input and is quite eager to change direction, yet it is extremely stable and always feels firmly planted. No matter if it’s speeding along in a straight line or heeled way over in a turn, it feels like it’s on outriggers. And unless the Paso is absolutely at its maximum lean angle—which, as we learned at Misano, is substantial —it allows you not just to change lines in a corner, but literally to “drive around” in the turn at will.

Tamburini’s cantilever-style frame is responsible for much of this handling magnificence. Fabricated of squaresection, chrome-molybdenum steel tubing, it is both light and rigid, and employs the engine as a stressed chassis member. His choice of steering geometry combines the light feel provided by an unusually steep (25-degree) head angle, with the directional stability imparted by an average amount ( 103mm) of trail.

Doing their part for the Paso’s fine handling are highquality suspension components, consisting of a flex-free Marzocchi M 1 R fork up front, and a single Ohlins shock at the rear. The damping-adjustable Ohlins works through a beefy aluminum swingarm and a forged aluminum linkage that uses sealed needle bearings at all pivot points.

Nevertheless, a sizable part of the chassis’ ability to amaze is owed to its extremely low-profile Pirelli MP7S radial tires—the first pure radiais included as original equipment on a production motorcycle. The Pirellis de-

liver an extraordinary amount of feel and feedback, while clinging to the road as though it were sheet metal and they were the world’s biggest refrigerator magnets. The use of 16-inch wheels at both ends, in combination with the exceptionally light weight and unusually small outside diameter of these 60-series, short-sidewall radiais, dramatically reduces the gyroscopic effect of the spinning wheels: thus, the Paso can be flicked over into a turn as abruptly and instantaneously as any full-size streetbike we’ve ever ridden.

Apart from the handling, the tires also contribute immensely to the Paso’s remarkable braking. We were easily able to generate enough force with the Brembo front discs to lift the rear wheel off the pavement at moderate speeds without causing even a hint of front-tire squirm or squeal. Not only that, you can trail the Paso’s brakes while entering—or even while in the midst of—a fast, hard turn, and the bike won't try to sit up and run toward the outside of the turn. To some extent, this is the by-product of intelligent steering geometry and a low center of gravity, but the Pirelli people insist that much of it is due to the design of their radial tires. Whatever the cause, it makes fast cornering almost absurdly easy.

What’s just as impressive is that the Paso offers such fine racetrack/sport-riding behavior without seriously detracting from its all-around streetability—which is, after all, its primary mission. As we found on the streets and highways in and around Rimini, the Paso’s ride is a pleasant compromise—not taut enough to be called harsh, not soft enough to be termed plush. It’s just . . . nice. The seat is contoured to allow serious knee-draggers to act out their finest Lucky Lucchinelli impersonations; but it’s also fairly thick, wellpadded and smartly shaped, and doesn’t turn a long ride on the open road into an exercise in self-abuse. And while the critical seat/bar/peg relationship is configured for competent sport riding, it allows decent long-range comfort, as well. Overall, in fact, there is a certain degree of similarity between the Paso’s ergonomics and those of some Japanese sportbikes, Honda’s VFR750 in particular.

But engine-wise, there are no similarities whatsoever between the Paso’s V-Twin and the multi-cylinder powerhouses found in Japanese sportbikes. The Paso will, however, have the most powerful 750cc Ducati engine that has ever been street-legal in this country. The engine is essentially in the same state of tune as the current 750 F1 motor, but with more-restrictive intake and exhaust systems to meet U.S. regulations. Of course, it retains the desmodromic valve system pioneered by Dr. Taglioni, with the bigger valves, more-radical cams and higher compression ratio that first appeared on the FI this year. The ignition system provides a smooth, gradual advance curve rather than the abrupt, two-step advance used previously, and an improved, dual-circuit oiling system better lubricates the cams and followers while also aiding engine cooling.

Really, the only big news in the engine department is the adoption of a single, automotive-style Weber two-barrel downdraft carburetor in place of the usual pair of sidedraft Dell’Ortos or Bings used on other Ducks. The Weber sits high in the vee of the cylinders atop a long intake manifold, under a large airbox that occupies a hollowed-out area at the front of the Paso’s 4.8-gallon gas tank. Ducati chose this carb for a number of reasons, not the least of which is Weber’s vast store of expertise in the rather knotty area of exhaust emissions.

That may be so, but there was no evidence of anyone’s carburetion expertise on the Paso we rode. It was more than willing to sputter and wheeze on certain occasions, usually when the throttle was whacked open from lower revs. But Taglioni & Co. assured us that they were on top of the problem, and that the Webers on production Pasos would carbúrate as crisply and cleanly as the carbs on current Ducatis, if not more so.

Because of those carburetion glitches—and a badly worn clutch that chattered violently when engaged under full throttle—decent quarter-mile launches were impossible; so our best quarter-mile ET was only 12.9 seconds. Most of the time, though, the Weber carb worked properly, allowing the engine to perform up to par. We clocked a respectable top speed of 131 mph, and we expect that a production Paso will click through the quarter-mile lights somewhere in the mid-12-second area.

Typical of Ducati V-Twins, the engine has a flat-as-aboard, completely usable power curve, with no discernable bumps or dips anywhere between 2000 or 2500 rpm and the 9000-rpm redline. When you want to go faster, you just open the throttle. And that, along with the Paso’s responsive steering and crisp handling, allows a moderately fast ride on a twisty backroad to be about as effortless an affair as you could ask for. Only when you want that ride to be a flat-out, take-no-prisoners assault is it necessary to make full use of the entire rpm range and the fivespeed gearbox. Agreed, the Paso normally is no VFR or GSX-R beater; but on just the right kind of tight backroad, it’ll give either of those 750cc hot-rods all they can handle.

Remember, however, that our impressions were obtained on a prototype motorcycle, so none of this information should be engraved in stone just yet. Not only was the carburetion in the final stages of development, but the bike we rode didn't even have mirrors or turnsignals. We saw a production taillight for the European market that had integrated turnsignals; and Tamburini showed us a prototype fairing that uses knock-off mirrors/turnsignals like those on the BMW K 1OORS. But yet another taillight, one w ith more widely spaced turnsignals, will be needed to gain DOT approval in the U.S.; and Ducati had only just begun the arduous process of meeting the EPA's noise and exhaust emissions requirements while we were in Italy. So at this stage, at least, the Paso still leaves a lot of

questions unanswered. But there is no question whatsoever that Massimo Tamburini has pointed the way to a bright new future for Ducati motorcycles. In style and in handling, his wonderful creation is fully competitive with Japanese machinery; in craftsmanship and in quality, it even promises to exceed anything the Japanese currently offer. And if Cagiva follows through on its intention to sell the bike in this country for about $5800, the Paso even should be fiercely competitive in the showroom—no small accomplishment fora “production-line Bimota.”

All of this is contingent, of course, upon the prototype Paso being faithfully duplicated on the assembly line. But unless Cagiva-Ducati commits a serious blunder somewhere along the way, the Paso is destined to be one of sportbiking’s most exciting performers in a long time. After all, it’s Italian. It's red. Most of all, it's right. Œ

CAGIVA-DUCATI 750 PASO

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson