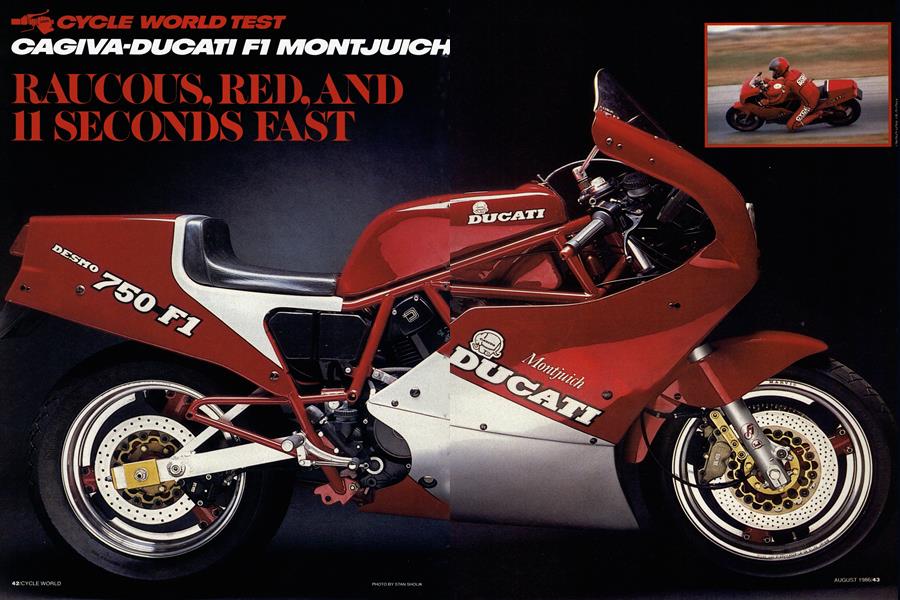

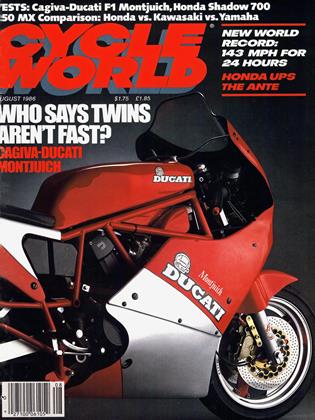

CAGIVA-DUCATI F1 MONTJUICH

CYCLE WORLD TEST

RAUCOUS, RED, AND 11 SECONDS FAST

SOMEWHERE, SOMEPLACE, THERE MUST BE A MAN who has heard only Muzak. Surrounded by its innocuous melodies in elevators and department stores, he may have finding it vaguely pleasant, and thought it as involving as music could be.

Imagine, then, this sheltered man found himself at a Rolling Stones concert. Sitting in a darkened concert hall, he'd he caught by the crowd's hush and anticipation before the start. His heart would begin beating faster. Then a wall of light and sound would overtake him, beat itself upon him. And like it or not, he'd be a million miles from Muzak.

Somewhere, someplace, there also must be people who believe that today's popular sportbikes represent the pinnacle of the motorcycling experience. A single ride on a Ducati Montjuich would shatter that belief as thoroughly as a Stones concert questions Muzak.

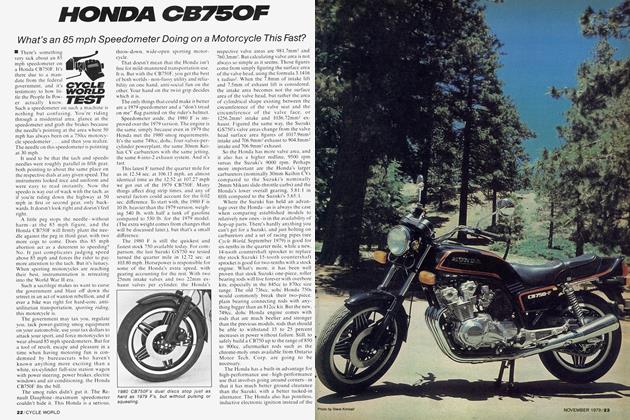

As red as a Ferrari, its filterless velocity stacks all agleam, the Montjuich makes no pretense of subtlety. Even its 1500-rpm idle is as lumpy and nasty as that of a race-cammed, open-piped V-Eight. Click down into first gear and accelerate hard, and the bike lifts its front wheel like a 747 on take-off, but with the thunder of a

NASCAR stocker instead of the whoosh of a jet.

This is a Twin that will cover a quarter-mile in the high elevens, with only a grabby clutch and a short wheelbase preventing it from running a few tenths quicker. This is a Twin that will run with, or even pull slightly, a Suzuki GSX-R750 down the long front straight at Willow Springs. In short, this is the quickest production Twin Cycle World has ever tested.

But such comparisons are not entirely fair. While the Cagiva-Ducati FI Montjuich is a production motorcycle (200 will be produced in 1986. only 10 of which will be sold in the United States), it’s not street-legal here, nor in most other countries. Its exhaust, while meeting competition standards, is simply too loud. Instead. Cagiva has produced a homologation special, a machine with minimal street equipment that can serve as a basis for its racing programs. But unlike some other competition machines, the Montjuich is delivered with lights and an electric starter, and is available from your Cagiva dealer.

Anyone who buys a Montjuich gets, in the steel and alloy of the bike itself, a history of Ducati’s racing milestones over the past few years. Ducati first housed special 600cc Pantah engines in monoshock trellis frames for

Italian championship events (where they trounced GPz550-engined Bimotas), and for international TT2 races (production-based 350cc two-strokes versus 600cc four-strokes). Later, bored and stroked to 748cc, Pantah engines were used in the same frame for TT 1 and endurance races, again with success.

While the Ducati factory was wobbling on its last fiscal legs in 1984, the 750 Fl, a street version of the TT1 racer, was announced. It would use a cooking version of the 750 race engine, with valve sizes the same as the 600 street engine, and mild cam timing; and the frame would be altered slightly to provide more rake and trail for slower steering, and slightly different tube placement for better engine access.

Despite Ducati’s plan, the FI nearly remained a fantasy, lost in the financial collapse of the Bologna-based producer of V-Twins. But Cagiva rescued and reorganized Ducati, and produced the FI in the thousands, instead of the hundreds Ducati originally intended. We tested one in Italy (September. 1985, issue), and found it a wonderfully fun. if not lightning fast, 750 sportbike.

But the FI, no matter how much fun, was a somewhat lacklust-er performer compared to its racing ancestors.

And while Ducati may have been willing to settle for that, Cagiva wasn't. The Castiglioni brothers, owners of Cagiva-Ducati. had already enticed Ducati V-Twin designer Dr. Fabio Taglioni from retirement to work on engine improvements. Surely, he could find more power in the 750 Pantah engine.

For the Montjuich he did. The 90-degree V-Twin Pantah engine, with two valves per cylinder, may seem somewhat dated, but it has responded well to Taglioni’s hot-rodding. Re-done cylinder heads now use 750cc-size valves: 41mm intakes and 35mm exhausts, compared with the 37.5mm and 33.5mm poppets on the 1985 FI engine. New camshafts hold these valves open 15 percent longer, while intake and exhaust overlap has more than doubled, from 67 to 137 degrees. Carburetor size is up, as well, with 40mm Dell'Orto pumpers replacing the 36mm units on the FI. The exhaust system, merely loud on the FI. has been replaced by a Morselli “full race" 2into-l equipped with a baffle a young boy could pass his fist through.

These changes have certainly increased power; an Italian magazine measured 75 horses at a Montjuich's rear wheel, a good number for a Four, a nearly incredible

figure for a 750 Twin.

But numbers don’t tell about this engine’s exceptional character. Despite its extreme cam timing, it will pull from 2000 rpm at partial throttle openings. At 4000 it runs stronger and will tolerate full throttle. Then, from 6500 rpm to the 9000-rpm redline and even 1000 rpm beyond, it accelerates truly hard, singing a song of power as pure and deep as the one played by Marco Luchinelli’s Daytona Battle-of-the-Twins-winning Ducati. The Montjuich bellows through the gears, with a sharp, metallic thunder, like a blacksmith hammering a glowing piece of steel thousands of times a minute. And on the overrun, it belches a hollow, haunting rasp that makes you understand why people once paid good money for recordings of four-stroke racing bikes at speed.

This 7 50 Twin will tolerate 10,000 rpm for brief bursts of acceleration, its mechanically positive desmodromic valve gear ensuring that valve float is non-existent. This engine will pull the front wheel up a foot with a hard shift into second. This engine loves to rev, but does so without feeling particularly peaky.

Carrying the engine is a chassis that’s at least as special. The Montjuich’s frame is right off of the FI, fabricated largely from straight tubes, with the engine acting as part of the structure. The gas tank is handmade from aluminum sheet, and, where it fits between the rider’s knees, is considerably narrower than the rear tire. The Montjuich, while a racer, cradles its rider more comfortably than a GSX-R, with more seat-to-footpegs room and less interference between rider and gas tank.

Unique to the Montijuich are truly special Marvic wheels, with cast centers that bolt to Akront aluminum rims. These exceptionally wide rims carry Michelin racing tires in 500cc Grand Prix sizes—4.6 inches wide in the front, and over 7 inches for the back. But despite the monster tires, the overall package is tiny, not all that much bigger than some 250s, and, at 367 pounds dry, exceptionally light. Even the addition of turnsignals (rubber plugs cover turnsignal mounting holes in the fairing the Montjuich shares with the regular Fl) and an effective muffler would still see this motorcycle weighing 50 pounds less than a GSX-R750. Stripped of electric starter and street gear for competition, it could easily approach 300 pounds.

So what does all this hardware yield in terms of a riding experience? The engine was every bit as impressive as described, but we initially found the chassis disappointing. The combination of the exceptionally wide, lowprofile tires, the narrow handlebars and the unusually large amount of trail (5.2 inches, compared with under 4 inches for most Japanese sportbikes) made steering very heavy at high speed and imprecise when going slow. Once we got more familiar with the bike, the handling felt better; and during testing at Willow Springs, the harder the Montjuich was ridden, the better it seemed to respond to steering input.

Suspension, however, was less than satisfactory. In our first laps at Willow, both wheels chattered over the small bumps that can be found on that track, bumps that disappear under the more-compliant suspensions of a Honda VFR or Suzuki GSX-R. A single adjustment knob on the Montjuich’s Marzocchi rear shock was able to render the rear suspension useless with either no perceptible damping, or so much of it that the rear end was essentially rigid. Fortunately, an intermediate position allowed the

rear end to work better, if not perfectly.

Not so with the Forcelle Italia fork; even with all adjustments set to their minimum values, excess friction and stiffness prevented the front wheel from accurately tracking the pavement. Steve Stortz, the U.S. distributor of F.I. forks, tells us this is atypical; whatever the cause, the fork on our test bike was simply not up to current standards.

We were able to improve upon some aspects of the Montjuich’s behavior a bit later in the test, while prepping the bike for competition in the La Carrera, a pointto-point roadrace held in Mexico (see “La Carrera,” pg. 48). We replaced the standard Michelin tires with slightly narrower, DOT-approved Michelin Hi-Sports ( 12,0/70-16 front, 160/80-16 rear). This change improved the steering, reducing both the turning effort and the Montjuich’s tendency to stand up while braking into a corner. The taller rear tire and a change from a 40-tooth to a 38-tooth rear sprocket allowed the Montjuich to reach an impressive 145 mph on the La Carrera’s long straights, with equally impressive stability. Still, less-conservative steering geometry would likely sacrifice little of that stability for even more responsive steering.

So in the end, the Montjuich is an impressive, soulful machine in search of a clear mission. It’s best suited as a Battle-of-the-Twins racer; it would require little modification to be competitive in the GP class; and if allowed in the stock class, it should easily dominate. The idea of street riding the Montjuich is tempting; but the anti-social exhaust note and the lack of paperwork necessary for legal registration render that proposition more than a little impractical.

Perhaps like the Rolling Stones, the Montjuich’s true home is in the past, in a 1960s setting where it could run with side-piped Corvettes and open-exhaust GTOs. Certainly, the safe and sane and noise-controlled Eighties will restrict it to closed-circuit use.

But the Montjuich also points to the future, and to Cagiva’s commitment to the Ducati V-Twin engine. Improvements such as the larger valves and refined carburetion will soon be incorporated into the street-going Cagiva-Ducati Paso, a machine that promises to have some of the Montjuich’s out-of-the-past character without offending present-day sensibilities.

But no matter; the Montjuich is its own reason for being, and the song it sings at 9000 rpm is so sharp and so pure that it needs no other excuse. El

CAGIVA-DUCATI

F1 MONTJUICH

$8800

View Full Issue

View Full Issue