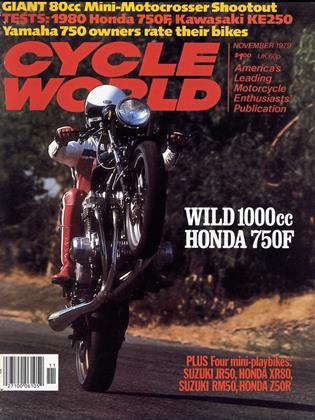

HONDA CB750F

CYCLE WORLD TEST

What’s an 85 mph Speedometer Doing on a Motorcycle This Fast?

There’s something very sick about an 85 mph speedometer on a Honda CB750F. It’s there due to a mandate from the federal government, and it's testimony to how little the People In Power actually know.

Such a speedometer on such a machine is nothing but confusing. You're riding through a residential area, glance at the speedometer and grab the brakes because the needle’s pointing at the area where 50 mph has always been on a 750cc motorcycle speedometer ... and then you realize. The needle on this speedometer is pointing at 30 mph.

It used to be that the tach and speedo needles were roughly parallel in fifth gear, both pointing to about the same place on the respective dials at any given speed. The instruments looked nice and uniform and were easy to read instantly. Now the speedo is way out of wack with the tach. as if you’re riding down the highway at 50 mph in first or second gear, only backwards. It doesn’t look right and doesn’t feel right.

A little peg stops the needle—without harm—at the 85 mph figure, and the Honda CB750F will firmly plant the needle against the peg in third gear, with two more cogs to come. Does this 85 mph abortion act as a deterrent to speeding? No. It just complicates judging speed above 85 mph and forces the rider to pay more attention to the tach. But it’s lunacy. When sporting motorcycles are reaching their best, instrumentation is retreating into the World War II era.

Such a sacrilege makes us want to curse the government and blast off down the srtreet in an act of wanton rebellion, and if ever a bike was right for hard-core, antiutilitarian transportation, sporting riding. this motorcycle is.

The government may tax you. regulate you, tack power-gutting smog equipment on your automobile, use your tax dollars to attack your sport, and force motorcycles to wear absurd 85 mph speedometers. But for a tool of revolt, escape and pleasure in a time when having motoring fun is condemned by bureaucrats who haven't known anything more exciting than a white, six-cylinder full-size station wagon with power steering, power brakes, electric windows and air conditioning, the Honda CB750F fits the bill.

The smog rules didn’t gut it. The Renault Dauphine-maximum speedometer couldn’t hide it. This Honda is a serious, throw-down, wide-open sporting motorcycle.

That doesn’t mean that the Honda isn’t fine for mild-mannered transportation use. It is. But with the CB750F, you get the best of both worlds—non-fussy utility and reliability on one hand, anti-social fun on the other. Your hand on the tw ist grip decides which it is.

The only things that could make it better are a 1979 speedometer and a “don’t tread on me” flag painted on the rider’s helmet.

Speedometer aside, the 1980 F is improved over the 1979 version. The engine is the same, simply because even in 1979 the Honda met the 1980 smog requirements. It’s the same 749cc. dohe, four-valves-percylinder powerplant, the same 30mm Keihin CV carburetors with the same jetting, the same 4-into-2 exhaust system. And it’s fast.

This latest F turned the quarter mile for us in 12.54 sec. at 106.13 mph. an almost identical time as the 12.52 at 107.27 mph we got out of the 1979 CB750F. Many things affect drag strip times, and any of several factors could account for the 0.02 sec. difference. To start with, the 1980 F is 10 lb. heavier than the 1979 version, weighing 540 lb. with half a tank of gasoline compared to 530 lb. for the 1979 model. (The extra weight comes from changes that will be discussed later.), but that’s a small difference.

The 1980 F is still the quickest and fastest stock 750 available today. For comparison. the last Suzuki GS750 we tested turned the quarter mile in 12.72 sec. at 103.80 mph. Horsepower is responsible for some of the Honda’s extra speed, with gearing accounting for the rest. With two 25mm intake valves and two 22mm exhaust valves per cylinder, the Honda’s respective valve areas are 981.7mm2 and 760.3mm2. But calculating valve area is not always so simple as it seems. Those figures come from simply figuring the surface area of the valve head, using the formula 3.1416 x radius2. When the 7.8mm of intake lift and 7.5mm of exhaust lift is considered, the intake area becomes not the surface area of the valve head, but rather the area of cylindrical shape existing between the circumference of the valve seat and the circumference of the valve face, or 1256.2mm2 intake and 1036.72mm2 exhaust. Figured the same way, the Suzuki GS750’s valve areas change from the valve head surface area figures of 1017.9mm2 intake and 706.9mm2 exhaust to 904.8mm2 intake and 706.9mm2 exhaust.

So the Honda has more valve area, and it also has a higher redline, 9500 rpm versus the Suzuki’s 9000 rpm. Perhaps more important are the Honda's larger carburetors (nominally 30mm Keihin CVs compared to the Suzuki’s nominally 26mm Mikuni slide-throttle carbs) and the Honda’s lower overall gearing, 5.81:1 in fifth compared to the Suzuki’s 5.65:1.

Where the Suzuki has held an advantage over the Honda—as is always the case when comparing established models to relatively new' ones—is in the availability of hop-up parts. There’s hardly anything you can't get for a Suzuki, and just bolting on carburetors and a set of racing pipes (see Cycle World. September 1979) is good for six-tenths in the quarter mile, while a new1, 14-tooth countershaft sprocket to replace the stock Suzuki 15-tooth countershaft sprocket is good for two-tenths w ith a stock engine. What’s more, it has been well proven that stock Suzuki one-piece, roller bearing rods will live forever w ith overbore kits, especially in the 845cc to 870cc size range. The old 736cc, sohc Honda 750s would commonly break their two-piece, plain bearing connecting rods with anything bigger than an 812cc kit. But the new', 749cc, dohc Honda engine comes with rods that are much beefier and stronger than the previous models, rods that should be able to withstand 15 to 25 percent increases in power w ithout failure. Still, to safely build a CB750 up to the range of 850 to 900cc, aftermarket rods such as the chrome-moly ones available from Ontario Motor Tech. Corp. are going to be necessary.

The Honda has a built-in advantage for high-performance use—high-performance use that involves going around corners—in that it has much better ground clearance than the Suzuki, with a better tucked-in alternator. The Honda also has pointless, inductive electronic ignition instead of the Suzuki’s breaker points system. The Honda, though, obviously has more valves to adjust.

More significant than the proven advantages that the Honda holds over its main competitor—the GS750—are the changes and improvements made to the Honda itself between the 1979 and the 1980 model year.

The alterations start with the usual new paint trim, then progress into the functional. The 1979 CB750F had shock absorbers that were a disgrace—they faded very quickly under hard use and wore out in less than 500 mi. The 1980 Showa shocks didn’t fade in 10 hard sprint-race laps at Willow Springs Raceway and have adjustable damping as well as the usual adjustable spring preload. Compression damping can be set in one of two positions via a small lever located at the bottom of the shock body, betw een the sides of the clevis. The lever rotates a disc between the shock pressure tube and oil reservoir. The disc has different size orifices so that in one position the oil displaced by the shock piston—which descends under compression loads—is forced through relatively larger or smaller holes. The soft setting uncovers larger holes—the oil can thus be pushed through to the reservoir with less effort and more speed. The stift' setting uncovers smaller holes and makes the compression damping harder and more resistant to bottoming under big impacts encountered on rough pavement or at high speeds.

The rebound damping is similarly controlled by a rotating ring located just underneath the upper shock eye. The adjuster ring has three positions, and is connected to the main shock valve by an adjuster tube which encases the shock rod. The main valve has three different size orifices along its outer edge and an additional five arrayed closer to the center. Setting the ring so that the largest holes are uncovered yields the softest compression damping, and vice versa. A blow -off spring releases excess pressure from spike loads on the shock.

For both the compression and rebound damping, the lower setting number is the softer setting.

Honda recommends that the rebound and compression damping be set at the softest position for a single rider at normal speeds without luggage; at medium rebound and stift' compression for a single rider at high speed w ithout luggage; and stiff rebound and stift' compression for riding double with luggage.

In actual use. the changes in damping made only subtle differences in the ride. One staff member who weighs about 150 lb. took the F out to experiment with the damping settings. On a concrete highway at cruising speeds, the ride seemed too stift', so he set the compression and rebound damping at the No. 1 settings, or soft. The ride was choppy, and resetting the compression damping to the No. 2, medium, position didn’t help. Conclusion one; soft on both damping settings is best for freeway use.

For high speed riding on a twisty smooth, road, the stift'position on rebound and soft on compression worked best—the stiff compression damping position made the ride too severe. Conclusion two: stift'on rebound and soft on compression is best on smooth, twisty roads at high speed.

The shocks are also slightly longer for 1980. measuring 14.25 in. from eye to eye compared to last year’s 14.0 in., and because of the extra complexity, they weigh more, 4 lb. 6 oz. compared to 1979’s 3 lb. 9 oz. Because the adjuster rod sheaths the shock rod. the apparent rod outside diameter is increased from 10mm to 14mm, but we're not sure how much ofthat is actually shock rod and how' much is the extra, hollow adjuster rod.

There have been small geometry changes as well. Triple clamp offset was increased 5mm to reduce trail 0.2 in., a change which makes the steering slightly quicker for steering more precisely approaching neutral, but a change which is hard to detect even when weaving through traffic at slow speeds and just about impossible to note at speed when using memory to attempt to compare the 1979 and 1980 versions.

The swing arm for 1980 now pivots on needle roller bearings instead of the cheap, flimsy-looking oil-less nylon (plastic) plain bushings used in 1979. Because the roller bearings have a larger o.d., the sw ing arm pivot itself is larger in o.d., up to 16mm from the previous 14mm. The swing arm itself is beefier, w ith tubing wall thickness increased from 2.0mm to 2.5mm and gusset plate thickness increased from 1.6mm to 2.0mm.

The changes to the sw ing arm pivot and the sw ing arm itself are not apparent w hen the Honda is ridden on street tires regardless of speed, at least not w hen compared to a 1979 CB750F with relatively new swing arm bushings. But the roller bearings can be expected to last longer and better control the sw ing arm itself, the first point being important to anybody and the second point being important to racers who plan on campaigning their F model with stickier-than-stock tires. For owners of older Fs. however, better quality, more stable bronze bushings are available from Ontario Moto Tech Corp. to replace the oil-less nylon stock bushings.

The tires themselves are better than they were last time around, providing much better traction and control while spending less time slipping and sliding when the hike is charged out of corners. The differences were most apparent at Willow Springs when the tires were good and hot. The Dunlop Fil and K127 tires found on our last CB750F were really bad and showed it by wearing out in about 100 hard pavement miles—tire slip accelerates wear. The Bridgestone Mag-Mopus S703 and S710 were far better in all types of control, especially when accelerating hard off' a corner. The new tires didn’t significantly affect stopping distances, as our 1980 F stopped in 31 ft. from 30 mph and in 135 ft. from 60 mph. compared to 30 ft. from 30 mph and 131 ft. from 60 mph for the 1979 ‘model. That tiny difference could be caused by the rider or available pavement traction on that particular test day. It should be noted that the 1980 F didn’t have the 1979 version’s pulsing and squealing brake problems—the discs simply worked and worked well.

But one problem that surfaced with this latest F that didn’t happen with the 1979 Honda we tested was a wobble at high speed (above 100 mph). All it took was a bump to set offa handlebar oscillation in a straight line at those speeds, with the mirrors in place and the rider sitting upright. One time when traveling into a headwind with the rider pulling on the bars hard to isit upright, the CB750F’s oscillation progressed into a moderate speed wobble, not enough to disturb staffers used to tank slappers on the racetrack, but surely enough to upset the average, non-racer street rider. Only tucking in calmed the bike, and that set a lot of heads to scratching.

Many things can affect motorcycle straight-line stability at speed in our experience, including—depending upon the model—whether or not both mirrors are in place, the location and weight of luggage tied on the machine (a rack is probably the >worst place to carry heavy loads as far as stability goes); wheel alignment (our 750F checked out perfectly, and the stamped swing arm alignment marks were actually accurate); brand and model of tire; and tire wear.

In the case of this particular bike, the ^problem was traced to a worn rear tire, which had accumulated 2300 street and racetrack miles as well as a dozen drag strip passes. Doing burnouts before the drag strip runs flattened the center of the tire and the uneven wear caused the wobble problem, which disappeared with the installation of a new tire.

Other changes for the 1980 model include reversed-spoke. black highlighted, all-aluminum ComStar wheels and green instrument lighting. The instruments were easier to read with the green lighting than they were with the red lighting used last year, although the tripmeter was still poorly illuminated. Also poor—and the same as last year—is the design of the oil pressure failure warning light lens, which often catches low-angle sunlight and appears to be lit. Even if the thing came on, the chances of the rider seeing it in broad daylight aren't very great.

The gas tank still resonates at the engine's vibration peak of about 4700 to 5000 rpm. and the new #530 sealed o-ring drive chain still rattles against the chain guard and makes a lot of noise, even though it’s supposed to be quieter (and longer lasting, due to the use of higher quality materials) than the larger #630 chain used for 1979. And, as last year, the CB750F pops out of fourth gear (and often misses third altogether) frequently during full-throttle acceleration unless the rider makes an effort to stick the bike positively in gear. It can be dealt with, but even the man who used to race a DKW (Remember famous Sachs engine false neutrals?) missed shifts and had the Honda popping out of gear at the dragstrip.

As always, the Honda is a real champion of cold starts and fuel economy, thanks to the sophisticated Keihin constant velocity carbs. Unlike many big-bore street bikes, the Honda can be started on a chilly morning and ridden away in a matter of seconds without gagging or bogging. And nobody can argue that 48 mpg on the Cycle World mileage loop—a mixture of city and rural roads isn’t great for a 750. Cruising on the interstate highway at a steady 60 to 65 mph, the Honda once covered 212 mi. before requiring reserve— an astonishing 52 mpg.

The carbs do have a bit of flat spot—or hesitation —when the rider is trying to slightly increase speed, turning the twist grip less than required to trigger the accelerator pump mounted on the carburetor bank. And at least one staff member noticed that those minute throttle adjustments had too much effect at lower cruising speeds, making finding and regulating an exact cruising speed difficult.

The 1980 CB750F also has a problem with pinging and detonating under acceleration w hen unleaded or regular gasoline is used. We didn’t have as much of a problem when commonly available premium fuels were used, but the bike would still ping coming off'a stop at low rpm. We tried adding octane booster on one occasion without success, and will report on further octane booster experiments in a future issue.

Seating position quality was a subject of hot debate, the 6 ft. 2 in. tourer on staff' liking it just fine and the shorter (5 ft. 10 in. and 5 ft. 11 in.) staff' members hating it, complaining of aching backs, cramped legs and w ind blasts taken in an unnatural position. Obviously, handlebar shape and footpeg location are items of personal preference and can be changed by a determined owner.

But aside from the personal feelings caused by the variety of body shapes and sizes found on this planet, beyond the minor complaints regarding carburetion and fourth gear, and the crazy, government-required speedometer, the Honda CB750F has become only better between the 1979 and 1980 model years. What it is is a social comment, a protest to government regulation and a damn good sporting motorcycle all in one.

HONDA

CB750F

SPECIFICATIONS

$2848

ACCELERATION

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1979 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1979 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1979 -

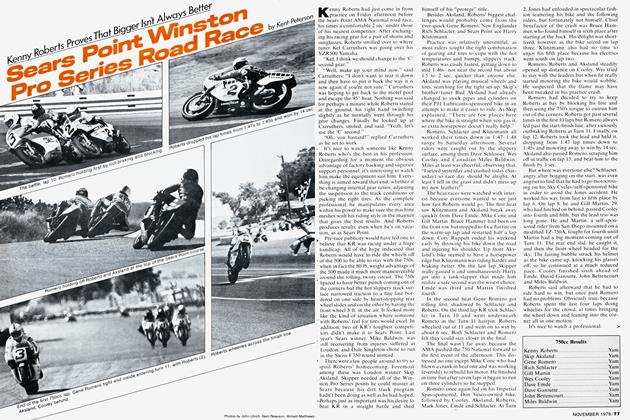

Competition

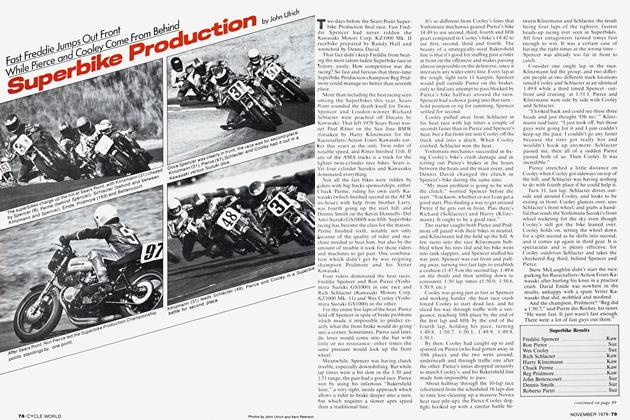

CompetitionSears Point Winston Pro Series Road Race

November 1979 By Kent Peterson -

Competition

CompetitionSuperbike Production

November 1979 -

Competition

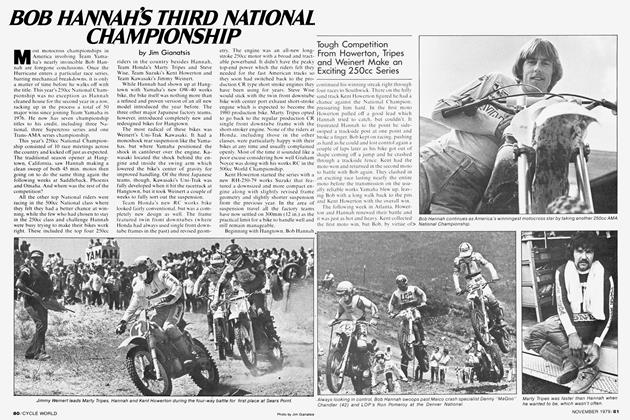

CompetitionBob Hannah's Third National Championship

November 1979 By Jim Gianatsis