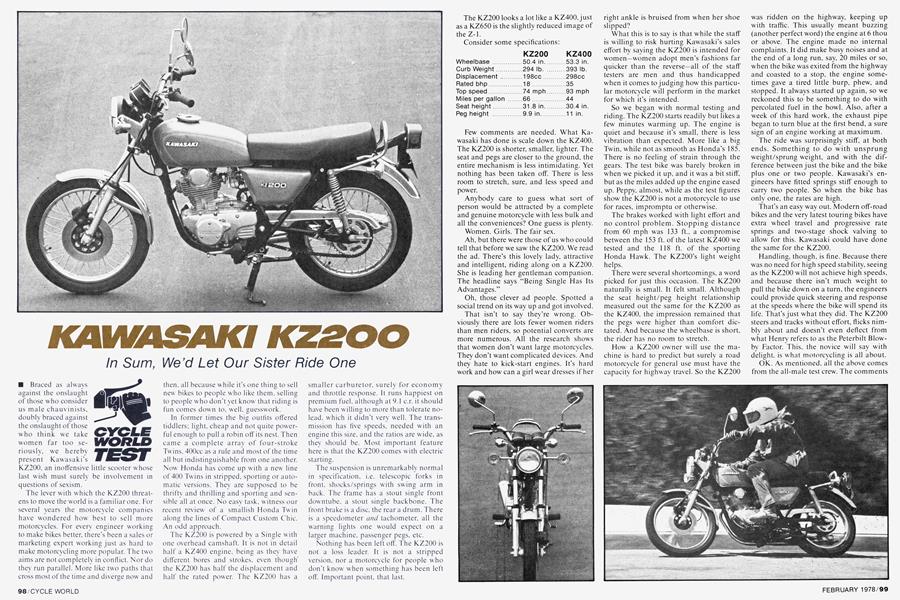

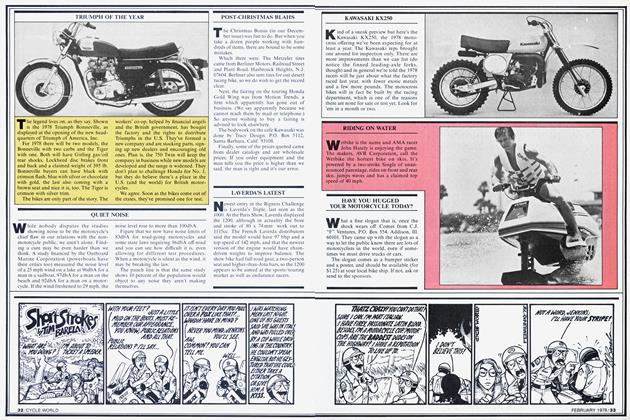

KAWASAKI KZ200

CYCLE WORLD TEST

In Sum, We'd Let Our Sister Ride One

Braced as always against the onslaught of those who consider us male chauvinists, doubly braced against the onslaught of those who think we take women far too Seriously, we hereby present Kawasaki's KZ200, an inoffensive little scooter whose last wish must surely be involvement in questions of sexism.

The lever with w hich the KZ200 threatens to move the world is a familiar one. For several years the motorcycle companies have wondered how best to sell more motorcycles. For every engineer working to make bikes better, there’s been a sales or marketing expert working just as hard to make motorcycling more popular. The two aims are not completely in conflict. Nor do they run parallel. More like two paths that cross most of the time and diverge now and then, all because while it’s one thing to sell new bikes to people w ho like them, selling to people who don't yet know that riding is fun comes down to. well, guesswork.

In former times the big outfits offered tiddlers; light, cheap and not quite powerful enough to pull a robin off its nest. Then came a complete array of four-stroke Tw ins. 400cc as a rule and most of the time all but indistinguishable from one another. Now Honda has come up with a new line of 400 Twins in stripped, sporting or automatic versions. They are supposed to be thrifty and thrilling and sporting and sensible all at once. No easy task, witness our recent review of a smallish Honda Twin along the lines of Compact Custom Chic. An odd approach.

The KZ200 is powered by a Single with one overhead camshaft. It is not in detail half a KZ400 engine, being as they have different bores and strokes, even though" the KZ200 has half the displacement and half the rated power. The KZ200 has a smaller carburetor, surely for economy and throttle response. It runs happiest on premium fuel, although at 9.1 c.r. it should have been willing to more than tolerate nolead. which it didn’t very well. The transmission has five speeds, needed with an engine this size, and the ratios are wide, as they should be. Most important feature here is that the KZ200 comes with electric starting.

The suspension is unremarkably normal in specification, i.e. telescopic forks in front, shocks/springs with swing arm in back. The frame has a stout single front downtube, a stout single backbone. The front brake is a disc, the rear a drum. There is a speedometer and tachometer, all the warning lights one w'ould expect on a larger machine, passenger pegs, etc.

Nothing has been left off. The KZ200 is not a loss leader. It is not a stripped version, nor a motorcycle for people w ho don't know' w'hen something has been left oflf. Important point, that last.

The KZ200 looks a lot like a KZ400, just as a KZ650 is the slightly reduced image of the Z-l.

Consider some specifications:

Few comments are needed. What Kawasaki has done is scale down the KZ400. The KZ200 is shorter, smaller, lighter. The seat and pegs are closer to the ground, the entire mechanism is less intimidating. Yet nothing has been taken off. There is less room to stretch, sure, and less speed and power.

Anybody care to guess what sort of person would be attracted by a complete and genuine motorcycle with less bulk and all the conveniences? One guess is plenty.

Women. Girls. The fair sex.

Ah, but there were those of us who could tell that before we saw the KZ200. We read the ad. There’s this lovely lady, attractive and intelligent, riding along on a KZ200. She is leading her gentleman companion. The headline says “Being Single Has Its Advantages.”

Oh, those clever ad people. Spotted a social trend on its way up and got involved.

That isn’t to say they’re wrong. Obviously there are lots fewer women riders than men riders, so potential converts are more numerous. All the research shows that women don’t want large motorcycles. They don’t want complicated devices. And they hate to kick-start engines. It’s hard work and how can a girl wear dresses if her right ankle is bruised from when her shoe slipped?

What this is to say is that while the staff is willing to risk hurting Kawasaki’s sales effort by saying the KZ200 is intended for women—women adopt men’s fashions far quicker than the reverse—all of the staff testers are men and thus handicapped when it comes to judging how this particular motorcycle will perform in the market for which it’s intended.

So we began with normal testing and riding. The KZ200 starts readily but likes a few minutes warming up. The engine is quiet and because it’s small, there is less vibration than expected. More like a big Twin, while not as smooth as Honda’s 185. There is no feeling of strain through the gears. The test bike was barely broken in when we picked it up, and it was a bit stiff, but as the miles added up the engine eased up. Peppy, almost, while as the test figures show the KZ200 is not a motorcycle to use for races, impromptu or otherwise.

The brakes worked with light effort and no control problem. Stopping distance from 60 mph was 133 ft., a compromise between the 153 ft. of the latest KZ400 we tested and the 118 ft. of the sporting Honda Hawk. The KZ200’s light weight helps.

There were several shortcomings, a word picked for just this occasion. The KZ200 naturally is small. It felt small. Although the seat height/peg height relationship measured out the same for the KZ200 as the KZ400, the impression remained that the pegs were higher than comfort dictated. And because the wheelbase is short, the rider has no room to stretch.

How a KZ200 owner will use the machine is hard to predict but surely a road motorcycle for general use must have the capacity for highway travel. So the KZ200

was ridden on the highway, keeping up with traffic. This usually meant buzzing (another perfect word) the engine at 6 thou or above. The engine made no internal complaints. It did make busy noises and at the end of a long run, say, 20 miles or so, when the bike was exited from the highway and coasted to a stop, the engine sometimes gave a tired little burp, phew, and stopped. It always started up again, so we reckoned this to be something to do with percolated fuel in the bowl. Also, after a week of this hard work, the exhaust pipe began to turn blue at the first bend, a sure sign of an engine working at maximum.

The ride was surprisingly stiff, at both ends. Something to do with unsprung weight/sprung weight, and with the difference between just the bike and the bike plus one or two people. Kawasaki’s engineers have fitted springs stiff enough to carry two people. So when the bike has only one, the rates are high.

That’s an easy way out. Modern off-road bikes and the very latest touring bikes have extra wheel travel and progressive rate springs and two-stage shock valving to allow for this. Kawasaki could have done the same for the KZ200.

Handling, though, is fine. Because there was no need for high speed stability, seeing as the KZ200 will not achieve high speeds, and because there isn’t much weight to pull the bike down on a turn, the engineers could provide quick steering and response at the speeds where the bike will spend its life. That’s just what they did. The KZ200 steers and tracks without effort, flicks nimbly about and doesn’t even deflect from what Henry refers to as the Peterbilt Blowby Factor. This, the novice will say with delight, is what motorcycling is all about.

OK. As mentioned, all the above comes from the all-male test crew. The comments are valid. If we don’t want this model for ourselves, it’s only because the KZ200 didn’t have enough power. Valid findings, we decided, but perhaps not quite on target.

KAWASAKI

KZ200

$859

Paraphrasing Freud, what do women want in a motorcycle?

While there are ladies on the staff, they are themselves beginning riders. They liked the KZ200 but all agreed they were not yet experienced enough to evaluate the machine.

Solution: Cecilia Manney. Henry Manney is a fond father. He is not a permissive parent. Henry isn’t the sort of person who turns the kid loose in the family hack just because the kid has managed to snake through driver’s ed. Until Henry’s children can drive (or ride) well enough to satisfy the Old Man, they aren’t allowed to have licenses.

Cecilia Manney is a college student, with a part-time job and a motorcycle operator’s license. She’s been riding since she was knee high to an Indian 50. Cecilia Manney was thus the perfect person to evaluate this lady’s speedy runabout.

Her report:

Comments: “At 55 mph, the engine is turning 6300 rpm. Isn’t that a little high?

“The engine runs better on Super than on non-leaded.

“The turn signal switch is off center and it’s hard to tell whether the switch is on or off.

“It sounds like an airplane at 55 mph.”

Bad points: “There’s no torque in top gear and you have to go flat out up hills. The fuel petcock is extremely stiff. The riding position is too cramped. There’s not enough distance between footpegs and seat. The clutch is abrupt and it’s hard to get smooth shifts. There’s too much extra stuff like parking lights and electric start. (!? . . . ed.)

“There’s a large clonk when shifting from neutral to first. The grips are too thin. The bike weighs a ton. The center stand is hard to use and the bike doesn’t balance well on it. It’s easy to burn the inside of your ankle on the crankcase, even with socks on. The gear lever is too low, which is easily fixed. And the suspension is stiff.”

Good points: “The engine is smooth and quiet. (I can barely hear it.) There’s good compression braking and good high speed acceleration between 55 and 60 mph. It’s very stable at all times and the cornering is beautiful. Good, quick brakes, no excessive vibration, a comfortable seat and a comfortable ride for and with a passenger.

“I didn’t have a chance to try it in the wet but the tires are fine otherwise. They

aren’t bothered too much by rain grooves on the freeway. All switches are on the handlebars and are easy to get to. The owner’s manual is excellent, very explicit.” Her findings?

“It’s a nice bike but I wouldn’t want one for myself. Not enough power.”

That’s a surprise, while not quite a surprise. All this concern over the differences between men and women—hurray for the differences!—and it turns out an evaluation done by an experienced female motorcycle enthusiast is impossible to distinguish from an evaluation done by an experienced male motorcycle enthusiast.

Meanwhile, Cecilia went off to put break-in miles on her dad’s new Yamaha XT500, the power of which she enjoys a lot, and the male staff members took another look at the KZ200.

We wish it well. The KZ200 is as honest and straightforward an entry-level motorcycle as has ever been offered to the public. It’s clean, tidy and completely without gimmicks while having all the equipment any rider could want. Primary considerations in terms of weight, size and economy have caused its only serious weak point, the lack of power. When the new rider gets to that stage, he or she will have a good background in basic road machines.

In sum, we’d let our sister ride one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

Features

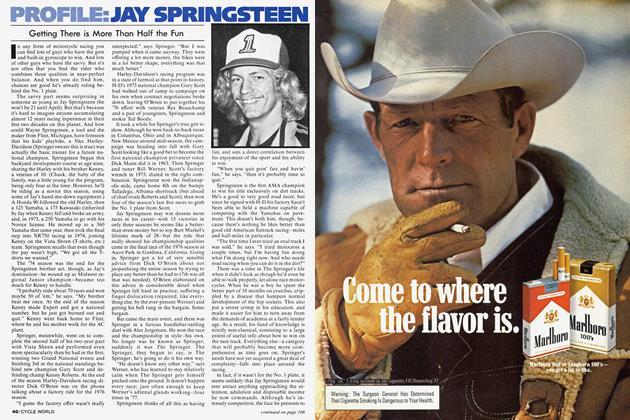

FeaturesProfile: Jay Springsteen

February 1978 -

Competition

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas