HONDA 450 REBEL AND SUZUKI SAVAGE

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

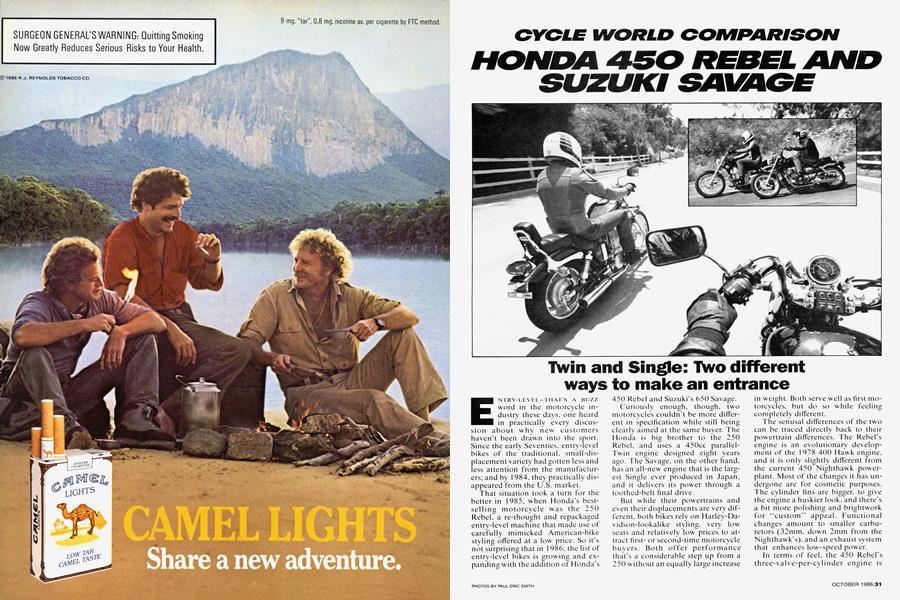

Twin and Single: Two different ways to make an entrance

ENTRY-LEVEL-THAT'S A BUZZ word in the motorcycle industry these days, one heard in practically every discussion about why new customers haven’t been drawn into the sport. Since the early Seventies, entry-level bikes of the traditional, small-displacement variety had gotten less and less attention from the manufacturers; and by 1984, they practically disappeared from the U.S. market.

That situation took a turn for the better in 1985, when Honda’s best-selling motorcycle was the 250 Rebel, a re-thought and repackaged entry-level machine that made use of carefully mimicked American-bike styling offered at a low' price. So it's not surprising that in 1986. the list of entry-level bikes is growing and expanding with the addition of Honda’s 450 Rebel and Suzuki's 650 Savage.

Curiously enough, though, two motorcycles couldn't be more different in specification while still being clearly aimed at the same buyer. The Honda is big brother to the 250 Rebel, and uses a 450cc parallelTwin engine designed eight years ago. The Savage, on the other hand, has an all-new engine that is the largest Single ever produced in Japan, and it delivers its power through a toothed-belt final drive.

But while their powertrains and even their displacements are very different, both bikes rely on Harley-Davidson-lookalike styling, very low seats and relatively low prices to attract firstor second-time motorcycle buyers. Both offer performance that’s a considerable step up from a 250 without an equally large increase in weight. Both serve well as first motorcycles, but do so while feeling completely different.

The senusal differences of the two can be traced directly back to their powertrain differences. The Rebel’s engine is an evolutionary development of the 1978 400 Hawk engine, and it is only slightly different from the current 450 Nighthawk powerplant. Most of the changes it has undergone are for cosmetic purposes. The cylinder fins are bigger, to give the engine a huskier look, and there’s a bit more polishing and brightwork for “custom" appeal. Functional changes amount to smaller carburetors (32mm. down 2mm from the Nighthawk’s), and an exhaust system that enhances low-speed power.

In terms of feel, the 450 Rebel’s three-valve-per-cylinder engine is very much like most other Honda parallel Twins: competent but not much in the way of excitement. It's very smooth and rev-willing, and offers a bit more mid-range than in most of its earlier incarnations. Some buzziness intrudes at the highest engine speeds, but the gearbox is never a bother; all six speeds can be obtained with short, easy movements of the gearshift pedal.

Suzuki’s Savage is entirely different. Its air-cooled. 652cc Single is allnew, an up-to-the-minute, four-valve design that bears some resemblance to the company’s SP600 dual-purpose engine. But this long-stroke Single doesn’t feel Japanese contemporary. It pulls strongly from just off idle, then flattens out quickly, asking to be short-shifted. It has substantial crankshaft mass that slows engine response and gives a hint of notchiness to what would otherwise be a smooth-shifting transmission.

That transmission has only four speeds (no other large Japanese motorcycle since the 1960s has had less than five gearbox ratios), and thanks to a seemingly dead-flat power curve, no more are needed; once top gear is reached, there’s little call to shift back down. The torquey Savage will quickly disappear from the Rebel in a roll-on contest. The vibration that might be expected from a 650 Single is present on the Savage, but it's wellmuted at speeds below 65 by a geardriven counterbalancer inside the cases. At higher speeds, the handgrips buzz and the Savage shakes, but not intolerably; overall, the Suzuki is far smoother-running than, say, a Harley Sportster.

In character, though, the Savage and the Sportster have much in common. Both offer the same sort of lazy, low-rev, no-shifting power accompanied by the individual thumps of big cylinders firing. Like the Sportster, the Savage has a sweet spot that is evident when cruising between 55 and 60 mph; at that speed there are times when the engine’s firing rhythm seems to resonate with the rider's alpha waves, lulling him and offering the perfect no-hurry platform from which to watch the w'orld go by. Under the same conditions, the Rebel whirs away reliably, but not as pleasantly.

Just as the Savage has replicated some made-in-Milwaukee engine characteristics, so do both it and the Rebel borrow' their riding position from Harley heritage. The Suzuki, however, is the more faithful and better re-creation, mostly because of its greater expansiveness. The Rebel has a wider engine that causes its forward-mounted footpegs to be farther apart than the Savage’s; that forces the pegs to be higher, as well, to prevent them from scraping in mild turns, but also making taller riders feel cramped. The Rebel’s pullback handlebar is fine around town, but because it forces a more leaned-back riding position, it is less suitable than the Savage’s straight, flat bar for highway travel; after as little as 20 miles at 55 to 65 mph on the Rebel, some riders will have had enough. In contrast, the Savage’s riding position works comfortably both in tow n and on the road.

The Rebel does offer some advantages over the Savage; better lowspeed steering is one. The 450’s steering is neutral at all speeds, and the bike could easily traverse a walkingpace obstacle course. The Savage, however, is comparatively unwieldy below 20 mph. At low speeds, its front wheel wants to fall into corners, probably as the result of almost chopperish amounts of front-fork rake combined with substantial offset built into the triple clamps. This tendency makes the Savage feel clumsy initially, until its rider learns to compensate; and as such, perhaps this isn't an ideal characteristic for a bike targeted at new riders.

At higher speeds, the Rebel keeps its light, neutral steering, but the Savage changes completely, developing enough stability for two motorcycles; any change in direction requires a healthy tug on the handlebar. And this suits the Savage’s character: It is a loping. Then Came Bronson cruiser, a machine from which to see the scenery as you ride by, not a twitchy sportbike. True, the Savage is light enough that you can toss it about if you're willing to work the handlebar, but it'll be happier if you relax.

Neither Savage nor Rebel has as much ground clearance as it has traction. but both can be ridden quickly enough before their pegs drag. More important is suspension quality, an area where the Rebel possesses yet another advantage, for it has enough travel to absorb most bumps. On lessthan-perfect roads that fail to disturb the Rebel, the Savage will occasionally bottom its rear suspension, adding harshness that really doesn't have to be there.

Bronson would have been happy with the Savage's tank-mounted speedometer and indicator lights; he never wore a full-face helmet w hose chinbar obscured all hint of the gas tank. Checking your speed on the Savage when wearing that type of helmet requires tilting your head downward and taking your eyes off the road for an uncomfortably long time. The Rebel, with its more conventionally located speedometer (neither machine has a tach). has no such problem —but then again, its front-end design is much more cluttered. So the instrument design of these two bikes gives you a clear choice between style and function.

Actually, few competitive machines have offered clearer distinctions than this pair. The Rebel is a classic Japanese 450 Twin, repackaged in Harley-esque clothing. It performs all the usual accelerate/turn/ stop functions with typical Honda competence. But while it repeats the Harley look, it really doesn't have some of the details right, such as its cramped seating position. In the end, the Rebel can be appreciated for how well it works, but it might be a hard machine to love.

The Savage does more than just look like an American custom; it recreates the feel, as well. Ironically, its single-cylinder engine feels more like a big American V-Twin than some Japanese V-Twins do. and its riding position and handling are those of a bigger motorcycle; the Savage just doesn't feel like the small bike it is. Quirks the Savage certainly has, such as its low-speed handling and weird placement of the speedometer and ignition switch, but these peculiarities are offset by the sheer amount of fun the bike can provide.

Will either of these two machines repeat the success of Honda's 250 Rebel? Initial reports are that the $1999 Savage is selling well, if not in record-breaking fashion. But the Rebel 450 may have been bushwacked on its way to the marketplace by the rapidly rising value of the yen. Honda’s original intent was to sell the Rebel for well under $2000, but the bike arrived in America after the yen/dollar relationship shifted dramatically in favor of the Japanese currency, forcing the Rebel's price way up to $2398.

Still, while both the Rebel and the Savage are good motorcycles, the Savage is simply the more fun of the two. And at this year's price, it's an absolute bargain.

HONDA

450 REBEL

$2398

SUZUKI

SAVAGE

$1999

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

October 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

October 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1986 -

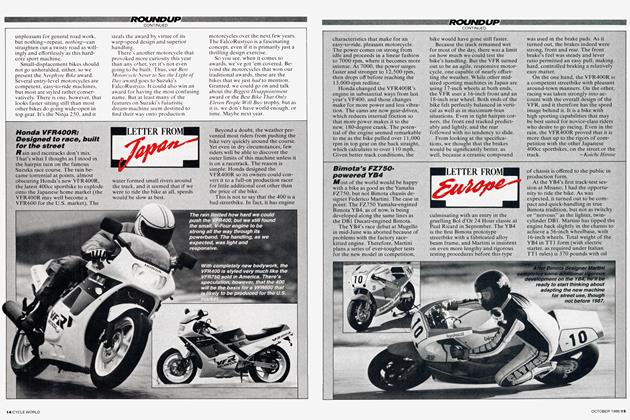

Roundup

RoundupBeyond the Ten Best

October 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

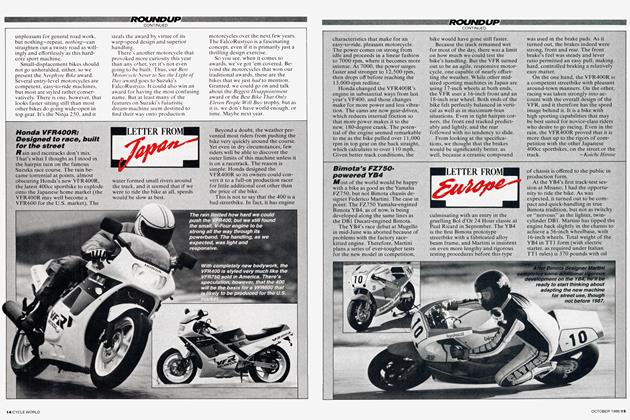

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1986 By Alan Cathcart