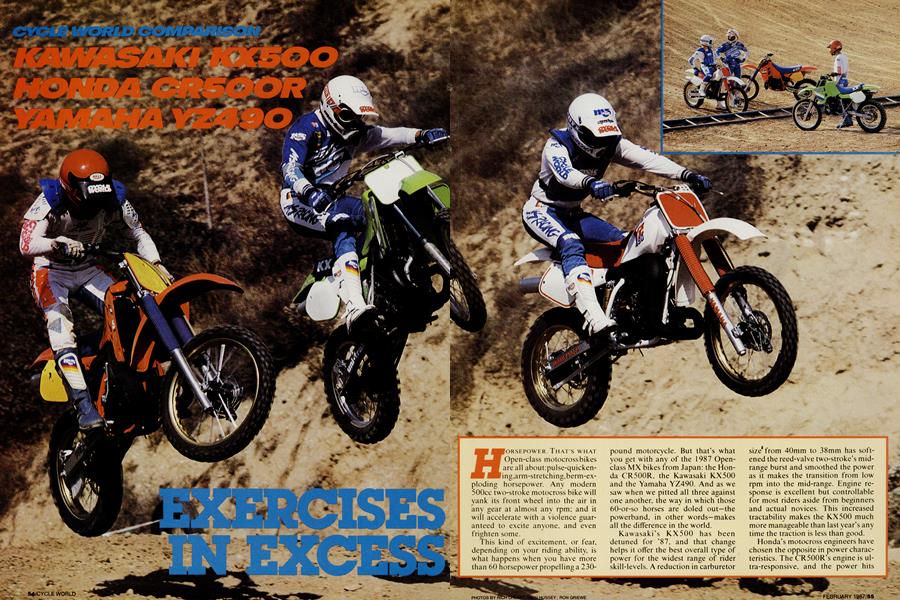

EXERCISES IN EXCESS

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

KAWASAKI KX500 HONDA CR500R YAMAHA YZ490

HORSEPOWER. THAT'S WHAT Open-class motocross bikes are all about:pulse-quickening,arm-stretching,berm-exploding horsepower. Any modern 500cc two-stroke motocross bike will yank its front wheel into the air in any gear at almost any rpm; and it will accelerate with a violence guaranteed to excite anyone, and even frighten some. This kind of excitement, or fear, depending on your riding ability, is what happens when you have more than 60 horsepower propelling a 230pound motorcycle. But that’s what you get with any of the 1987 Openclass MX bikes from Japan: the Honda CR500R, the Kawasaki KX500 and the Yamaha YZ490. And as we saw when we pitted all three against one another, the way in which those 60-or-so horses are doled out—the powerband, in other words—makes all the difference in the world.

Kawasaki's KX500 has been detuned for ’87, and that change helps it offer the best overall type of power for the widest range of rider skill-levels. A reduction in carburetor size* from 40mm to 38mm has softened the reed-valve two-stroke’s midrange burst and smoothed the power as it makes the transition from low rpm into the mid-range. Engine response is excellent but controllable for most riders aside from beginners and actual novices. This increased tractability makes the KX500 much more manageable than last year’s any time the traction is less than good.

Honda’s motocross engineers have chosen the opposite in power characteristics. The CR500R's engine is ultra-responsive, and the power hits hard dii low revolutions. Most Pro racers love it when a bike has this type of quick, powerful hit at the slightest twist of the throttle, but riders of lesser qualifications might have trouble dealing with the engine’s instant bursts of power. A normal blip of the throttle when leaving a jump, for example, tends to shoot the front wheel up fast enough to strike fear into all but the more experienced of riders.

Yamaha’s YZ490 engine, the only air-cooled motocross motor still in captivity, runs much more cleanly

The still than pings YZ’s past slightly powerband, versions when did, ridden like although hard. the KX’s, it is much improved, too. There’s more low-end power and the mid-range hit has been tamed, which results in a more linear overall power output. But the powerband is still far from being ideal; power builds in a rather erratic manner that gives the impression that the ignition system is malfunctioning, but it is actually the result of excessive silencing devices inside of the exhaust system. Even so, the ’87 motor’s power output is an improvement over that of past 490 engines, which generally had weak low-end performance before exploding with a mad burst of mid-range horsepower.

Controlling the massive power of any open-class bike places a big demand on the chassis—which, on all three of these bikes, is shared with its respective company’s 250cc motocross model. This parts-sharing—a common practice these days—helps reduce their cost of manufacture, as well as their retail prices. And none of these three seems to have any problems caused by sharing a chassis with a 250.

For example, the Honda has quick, positive, 250-like steering that lets the rider feel in control in all normal situations. It carves tight lines through corners and can change lines at the last moment, traits that help create a great sense of confidence. The only distracting factor in the CR’s chassis is the infamous Honda headshake when crossing high-speed bumps and when entering severely whooped corners.

Last year, Honda’s Showa cartridge-style fork set new standards for production motocross bikes; and since the fork is unchanged for ’87, that excellence continues. The Showa shock is new, though, with an unusual, sideways-mounted piggyback reservoir; the shock does a good job of controlling the rear of the bike, but not an exceptional job. The spring rates, front and rear, are perfect for most riders, though, and that helps the CR have an excellent level of comfort.

While the CR500R is the absolute king of precision in corners, the KX500 is not. In fact, it’s not the absolute best in any one area of motocross handling; but overall, it competently handles any bumps, turns and jumps a track can throw at it.

For ’87, the KX500 got a revalved KYB fork and a new KYB shock, along with a redesigned frame that locates the rear-shock linkage under the swingarm (same as on the ’86 KX 125). These changes help the biggest KX to get around a track without its rider expending excess energy. Cornering precision is quite good, even if it’s not as laser-beam perfect as the Honda’s, and the KX also has excellent straight-line stability across medium-sized bumps and whoops. The new fork valving has turned last year’s harsh front suspension into one than works nearly as well as the Showa on the CR; and the new shock has the best damping of any in this group.

But while Kawasaki’s engineers did an excellent job with damping rates, they blew it when choosing spring rates. The shock and fork springs are a little too soft when the bike is new, and they get progressively softer during every ride. After three or four long rides, the springs are way too soft. Kawasaki offers stiffer springs as options, and serious motocross racers should order them when they buy a KX500.

Then there’s the Yamaha chassis, which is little-changed from last year’s model. The frame now is painted white, and the rear shock has been slightly revalved, but the rest of the chassis is the same as in ’86. Still, the shock performs quite nicely on a wide variety of terrain—most of the time. A glitch occurs when entering a bumpy corner with the rear brake applied hard, which can make the rear suspension act up.

At the source of the problem is BASS (Brake Actuated Suspension System), a mechanism that reduces the shock’s compression damping when the rear brake is applied. A clever idea, except that it makes the rear suspension behave unpredictably from one corner to the next.

When braking into a bumped corner after a level-ground approach, the system helps the rear tire follow the bumps instead of jumping across them. But when the bike is entering a corner from a rough, downhill approach, the BASS system allows the rear suspension to bottom badly, and the bike hops and jumps into the turn. Most riders simply unhook the control cable between the brake pedal and the shock, which then allows the shock action to be constant.

Such a simple fix is not available for the fork. The spring rate is correct but there is too much compression damping. The fork is harsh on almost any irregular terrain, and the front tire hops across bumps when braking hard entering turns. A damper modification or a fork kit is needed to give the YZ a competitive front suspension. Actually, with a few fork and shock modifications, the YZ could be a thoroughly pleasant racer; it turns well and is very stable and controllable through smoother corners, and it has good high-speed, straight-line stability.

I he Yamaha is slightly less efficient in the brake department, too.

1 he disc front and drum rear feel fine until you jump onto the dual-disctquipped Kawasaki or Honda; both have stronger brakes that stop with less rider effort. The Honda’s brakes are especially nice; one finger on the handlebar lever will give all of the front stopping power most riders want. And the rear disc is by far the best we have used; it’s strong without being overly sensitive and it provides good feedback to the rider. Kawasaki's front brake requires a pull someplace between those required on the CR and the YZ. But the rear brake, unchanged from '86, locks easily and often stalls the engine, although most riders soon adapt to the light touch needed to slow the bike without locking the wheel.

Matter of fact, if you simply took the rankings of these bikes in terms of brake preformance, you would also know how they rate as all-around open-class motocrossers. The Yamaha YZ490, for example, finishes third in this comparison, for it requires the most modification—and, thus, the biggest dollar investment—to become truly race-ready. A fork kit is all but mandatory, and a new pipe and silencer are needed to eliminate the YZ’s erratic power delivery. Modifying the KX500 would be a much less costly proposition, but you'd still have to cough up around $125 for stiffer shock and fork springs.

Which brings us to the Honda CR500R, the only bike of the trio that needs no modifications before heading to the local motocross races—and being deadly competitive once it gets there. With careful use of the throttle, a reasonably strong desire to win, and the proper riding skills, a CR500R rider is destined to take many checkered flags. Even if his bike might scare him a few times along the way.

HONDA CR500R

$2998

KAWASAKI KX500

$2991

YAMAHA YZ490

$2949

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSeoul-Searching

February 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1987 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

February 1987 -

Roundup

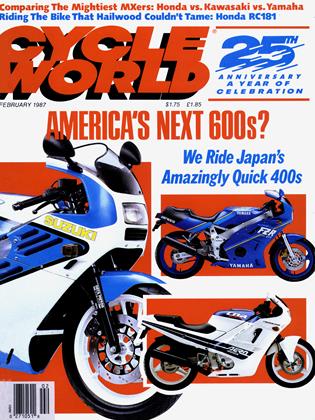

RoundupWill Japan's Cure For A Stagnant Market Work In America?

February 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupWhen School Is Meant To Be A Drag

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Entry-Level Sportbike: Destined For America?

February 1987 By Koichi Hirose