CAGIVA WMX125 VS. KAWASAKI KX125

CYCLE WORLD COMPARISON

AN UPSTART FROM ITALY TAKES ON THE CHAMP

TIME WAITS FOR NO MANUfacturer of motocross bikes. Especially in the highly combative 125 class. Put last year's totally new, awesome-everything, almost-unbeatable 125 in this year's races, and it will have a hard time staying out of last place.

The motorcycle manufacturers know this, but they all don’t deal with it in the same way. The Japanese, who place great value in 125class racing in America, do whatever they think is necessary to keep their 125s competitive. But in Europe, where the 500 class is the most prestigious, the 125s aren’t taken as seriously; so the European 125s that are shipped to America generally aren’t competitive at all.

But not always. KTM makes a genuine effort with its 125 from time to time; and lately, Cagiva’s new 125 has been surprising a lot of people, including the other 125-class riders it has been beating in various motocross and off-road races.

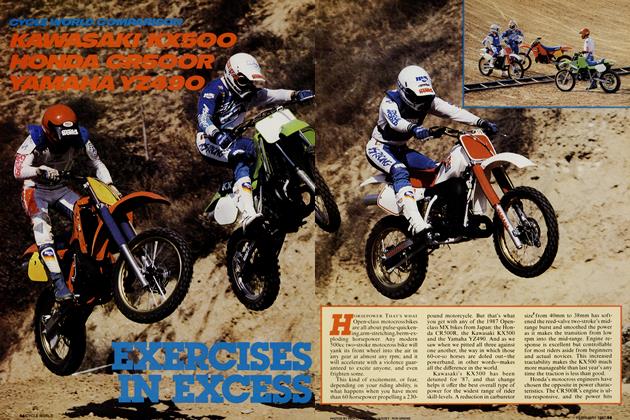

Obviously, the Cagiva is one European 125 that’s worth a closer look. So, because Kawasaki’s KX 125 is the hottest Japanese 125 on the tracks this year, we decided to put the Cagiva and the KX together for a little on-the-track warfare to decide which is the absolute 125-class king. Maybe the results won’t surprise you; but then again, maybe they will.

Despite having been built half a world apart using entirely different brands of components, these two bikes are very similar in execution and in specification. Each uses a twostroke engine that has a 56mm bore and a 50.6mm stroke, with reedvalve induction and an rpm-regulated exhaust-tuning device. Each has a six-speed transmission, liquidcooling, a single-shock rear suspension, a highly adjustable front fork, straight-pull wheel spokes, a disc front brake and an aluminum swingarm. They have less than a quarter of an inch of difference in wheelbase, and there is only a one-pound difference in dry weight.

Out on the track, the Cagiva and the Kawasaki again prove nearly equal, although they go about things in different ways. Both have a strong, competitive power output, but the KX125 has the wider powerband. The Kawasaki pulls fairly well right off of idle, revs quickly into and through the mid-range,and continues to pull strongly up into the high-rpm never-never land. The Cagiva’s engine doesn’t produce nearly as much low-end power as the KX’s, despite its flat slide-valve that regulates exhaust-port height. The Cagiva explodes with a potent surge in the midrange, but it signs off just as suddenly before it can reach ultra-high revs.

This burst of mid-range power can be very effective when exiting a turn, but the rider must constantly work the Cagiva’s clutch and shift levers to keep the engine within its narrow powerband. Keeping the KX in its much-wider powerband isn’t nearly as tiring. The Kawasaki also has an easier clutch pull, so it doesn’t pump up the rider’s left forearm as quickly as the stiffer clutch on the Cagiva. Although our Novice and Intermediate riders did occasionally miss downshifts into first gear on the Cagiva (the Pros never used low gear and so never had the problem), both bikes shift nicely, and have gear ratios that match their powerbands.

Both of these bikes also have some deadly-serious suspension systems. The Kawasaki uses a KYB shock and fork that are adjustable for spring preload, and for both compression and rebound damping. The Cagiva uses the latest piggyback-reservoir Ohlins shock and a Cagiva-designed, Marzocchi-built fork fitted with just one spring. The spring in the rightside fork leg is stiff enough to allow the elimination of the left spring. The fork’s damper rods are equally novel: The right damper controls the rebound damping, while the left damper takes care of the compression damping. Additionally, the fork caps are adjustable; the right one adjusts spring preload over a 10mm range, and the left one adjusts the progression of the overall spring rate by changing the volume of the airspace above the fork oil.

Separating the damper-rod functions affords an unusual tuning opportunity: The oil volume and/or oil weight in each fork leg can be adjusted independently. For example, we used 5-weight oil at a level of 3.2 inches in the compression (left) leg, and 1 5-weight at a level of 6.5 inches in the rebound leg. These settings helped reduce the fork’s roughness across small bumps and harshness on landings from jumps; but it still didn’t bring the performance of the Marzocchis up to that of the KX’s flawless Kayabas.

Neither can the Cagiva’s rear suspension match the Kawasaki’s for sheer smoothness. Both bikes go through whoops straight and true, but the Cagiva’s rear wheel doesn’t follow the terrain as well as the Kawasaki’s does. That causes the rider to feel more of the impact.

We found more rear-suspension differences during 20-minute races we staged between both bikes with Pros of equal ability aboard. The Kawasaki’s shock would not start heating up until the 20-minute mark, but the Ohlins on the Cagiva was redhot by the fifth lap (in 105-degree ambient temperature) and starting to bottom. By the end of each race, the Cagiva rider would have his hands full trying to control the bike as the shock simply boinged up and down.

The Kawasaki bettered the Cagiva in rider fit and comfort, as well. The KX’s seat is nicely shaped and only a little firm; the Cagiva’s seat has a good shape, too, but its foam is so incredibly hard that it offers all the comfort of a piece of wood. In addition, the Cagiva’s handlebar has a weird bend that puts the grips nearly in a straight line. Efforts to adjust the bar to the rear resulted in the grips pointing downward, so we gave up and replaced the stock handlebar with an Answer bar trimmed to 3 1 inches in width. We also replaced the Cagiva’s large-diameter, rock-hard grips with smaller, softer ones.

We kept the Cagiva’s stock Pirelli Hard Cross tires, however, because they performed better than the Kawasaki’s Dunlops on the rock-hard Southern California terrain. But braking-wise, we preferred the KX; both of these 125s have strong, predictable brakes at both wheels, but the Kawasaki’s front disc requires the least muscle.

Overall, in fact, we had quite a few such minor complaints about the Cagiva, but we were impressed with the bike anyway. It has has a solid, sturdy feel, is extremely well-made, and it gets around a motocross course quickly. The Cagiva does cost $136 more than the Kawasaki, but it also comes with a spare-parts kit and a workstand, which make up for the difference in the price. And the workmanship on the Cagiva is outstanding. The plastic parts are strong and beautifully made, and the welding on the frame and, in particular, the aluminum swingarm is near-perfect.

So there’s no doubt that the Cagiva 125 is a high-quality, truly competitive motocross bike. With some finetuning the suspension, a softer seat and a few personal changes, the Cagiva could be the very best 125.

But in stock form, it isn’t. The KX is the 125 that is ready to beat anything the competition can throw at it, straight from the shipping crate. And on top of everything else, it’s a genuine blast to ride. Every one of our test riders would come in from a ride on the KX grinning and babbling about the bike’s amazing power and the magical suspension that never seemed to get confused or misbehave in any way. The Cagiva is a mighty impressive machine that clearly shows that the Europeans can build competitive 125s. But just as it has been for the past two seasons, the KX 125 is the best 125 you can buy. 0

KAWASAKI X125

$1999

Kawasaki Motors Corp.

CAGIVA 125

$2135

Cagiva North America, Inc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Ties That Bind Usually

October 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeFighting Back

October 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1985 -

Roundup

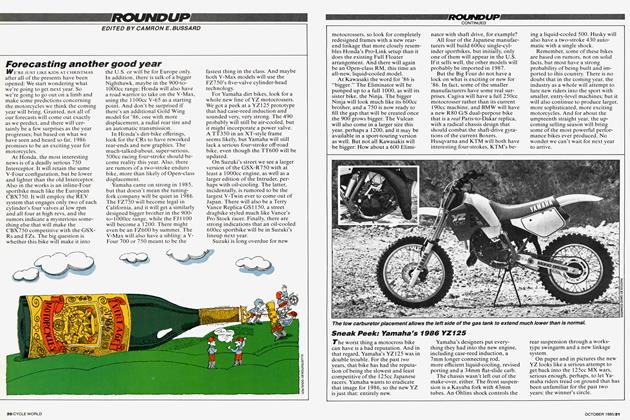

RoundupForecasting Another Good Year

October 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1985 By Alan Cathcart