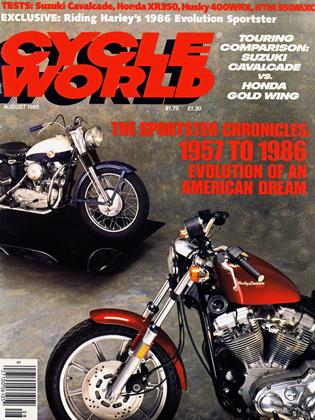

GENESIS OF AN EVOLUTION

After 28 years, the Sportster proves the old adage that the more some things change, the more they remain the same

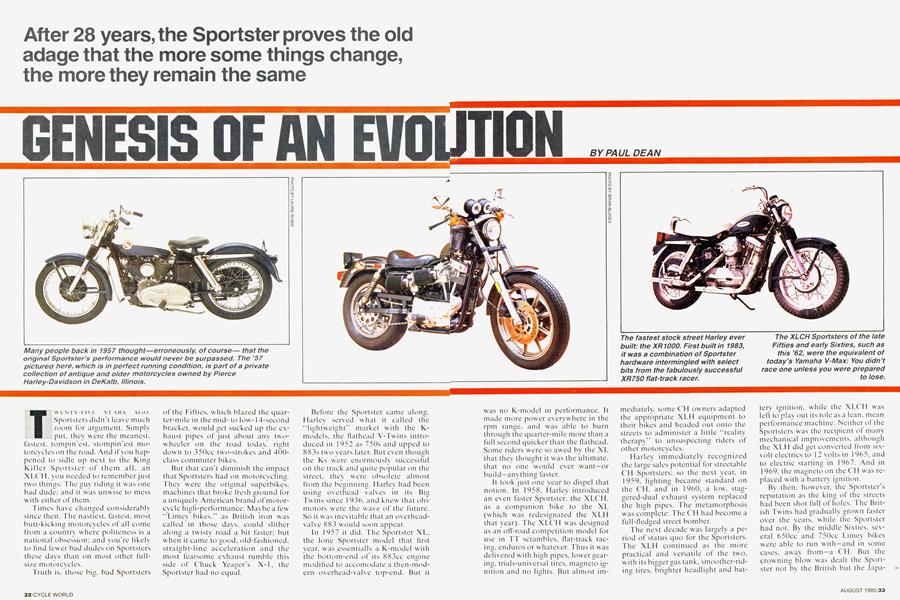

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO. Sportsters didn't leave much room for argument. Simply put, they were the meanest, fastest, rompin'est, stompin'est motorcycles on the road. And if you happened to sidle up next to the King Killer Sportster of them all, an XLCH, you needed to remember just two things: The guy riding it was one bad dude; and it was unwise to mess with either of them.

Times have changed considerably since then. The nastiest, fastest, most butt-kicking motorcycles of all come from a country where politeness is a national obsession; and you're likely to find fewer bad dudes on Sportsters these days than on most other fullsize motorcycles.

Truth is, those big. bad Sportsters of the Fifties, w hich blazed the quarter-mile in the midto low-14-second bracket, would get sucked up the exhaust pipes of just about any twowheeler on the road today, right down to 350cc two-strokes and 400class commuter bikes.

But that can't diminish the impact that Sportsters had on motorcycling. They were the original superbikes, machines that broke fresh ground for a uniquely American brand of motorcycle high-performance. Maybe a few “Limey bikes." as British iron was called in those days, could slither along a twisty road a bit faster; but w hen it came to good, old-fashioned, straight-line acceleration and the most fearsome exhaust rumble this side of Chuck Yeager's X-1, the Sportster had no equal.

Before the Sportster came along, Harley served what it called the “lightweight" market with the Kmodels, the flathead V-Twins introduced in 1952 as 750s and upped to 883s two years later. But even though the Ks were enormously successful on the track and quite popular on the street, they were obsolete almost from the beginning. Harley had been using overhead valves in its Big Twins since l 936. and knew that ohv motors were the wave of the future. So it was inevitable that an overheadvalve 883 would soon appear.

In 1957 it did. The Sportster XL. the lone Sportster model that first year, was essentially a K-model with the bottom-end of its 883cc engine modified to accomodate a then-modern overhead-valve top-end. But it was no K-model in performance. It made more power everywhere in the rpm range, and was able to burn through the quarter-mile more than a full second quicker than the flathead. Some riders were so awed by the XL that they thought it was the ultimate, that no one would ever want-or build-anything faster.

PAUL DEAN

It took]ust dne year to dispel that notion. In 1958. Harley introduced an even faster Sportster. the XLCH, as a companion bike to the XL (which was redesignated the XLH that year). The XLCH was designed as an off-road competition model for use in TT scrambles, flat-track rac ing. enduros or whatever. Thus it was delivered with high pipes. lower gear ing. trials-universal tires, magneto ig nition and no lights. But almost im mediately. some CH owners adapted the appropriate XLH equipment to their bikes and headed out onto the streets to administer a little "reality therapy~' to unsuspecting riders of other motorcycles.

Harley in~mediately recognized the large sales potential for streetable CH Sportsters: so the next year, in 1959, lighting became standard on the CH, and in 1960, a low, stag gered-dual exhaust system replaced the high pipes. The metamorphosis was complete: The CH had become a full-fledged street bomber.

The next decade was largely a pe riod of status quo for the Sportsters. The XLH continued as the more practi~.~al and versatile of the two, with its bigger gas tank, smoother-rid ing tires, brighter headlight and battery ignition, while the XLCH was left to play out its role as a lean, mean performance machine. Neither of the Sportsters was the recipient of many mechanical improvements, although the XLH did get converted from sixvolt electrics to 12 volts in 1965, and to electric starting in 1967. And in 1 969. the magneto on the CH was re placed with a battery ignition.

By then, however, the Sportster's reputation as the king of the streets had been shot full of holes. The Brit ish Twins had gradually grown faster over the years. while the Sportster had not. By the middle Sixties, sev eral 650cc and 750cc Limey hikes were able to run with-and in some cases, away from-a CH. But the crowning blow was dealt the Sport ster not by the British hut the Japa nese, who hit the beach in 1969 with two monumental bikes: the Kawasaki H 1 500 Triple and the Honda CB750 Four, either of which would blow' past a once-feared XLCH as though the Harley were chained to a tree. An era had ended.

Another era also ended that year: Harley-Davidson was bought—lock, stock and cast-iron barrels—by the giant AMF Corporation. The parent company’s management team, which quickly started calling some of the shots, figured that if Harleys could no longer keep up with the Japanese in terms of performance, they at least ought to keep up in styling. And so 1970 brought the infamous “boattail” Sportsters, AMF/Harley-Davidson’s answer to the growing dominance of Japanese motorcycles.

Buyers weren't impressed. The rocket-man tail section looked completely out of place on an otherwise traditionally styled motorcycle, and the Sportster’s stamped-steel, longmuffler exhaust system lent the bike an air of cheapness that H-D aficionados felt was more befitting the Japanese bikes of the day. So they stayed away in droves. But it took Harley a while to get the message, and the boat-tail hung around one more year.

In 1 972, however, not only did the Sportster return to a more traditional rear-end treatment, but it also got a 4.8mm-larger bore. That upped its displacement to 998cc, giving back to the engine all of the punch—and then some—it had lost over the years due to meeting various state and federal regulations. But the 1 OOOcc XLCH still wasn't up to the ever-escalating performance standards being established by the Japanese. The British hadn't been able to keep pace with Japanese technology, either, and had become a major fatality in the highperformance wars.

But Harley wasn’t about to roll over and play dead. In 1977, the company shocked the motorcycle world with the XLCR 1000 Café Racer, which was arguably the most controversial—and unarguably the fastest—Harley streetbike ever built up to that time. The CR’s power and handling, while not exactly at the cutting edge, were at least in the ballpark. The racy styling, which featured a quarter-fairing, an angular gas tank and acres of black paint, was uncharacteristically daring for Harley.

It was also an answer to a question nobody had asked. Because despite volumes of press coverage and considerable promotional fanfare. Café Racers moved ofif of the showroom floors very, very slowly. So slowly that just two years later, they were cut out of the Harley lineup, relegated to being much-sought-after by collectors of motorcycling memorabilia.

But the engineering lessons that Harley had learned with the XLCR were not completely in vain. In 1 979, Sportsters instantly became betterhandling, easier-riding motorcycles through the inheritance of a new' chassis that was a virtual copy of the Café Racer’s. 1979 also was the year in which the venerable XLCH was discontinued and replaced by a new' model, the XLS “Roadster.” The XLH remained the only model officially named the “Sportster.”

Long-time Sportster fans were saddened to see the XLCH pass on into extinction, but its demise was academic. The CH had been living on its name only, for its engine had been not one whit different than the XLH’s for years.

Nevertheless, Harley had not yet exhausted its repertoire of performance ideas. Since 1972, the company had been enjoying unprecedented flat-tracking success with the XR750, a competition-only machine with an alloy engine based loosely on the Sportster’s. All along, racing enthusiasts had been begging the company to build a street-legal version of the XR750, and all along, Harley had been explaining that such a machine was not feasible, that the XR would have a devil of a time meeting federal noise and emissions regulations.

Finally, in 1983, Harley-Davidson —free of AMF since 1981 and looking for new little market-segments to exploit—decided to give those enthusiasts the next-best thing to an XR750: an XR 1000. Built only in limited numbers, the XR1000 used XR750 dual-carb alloy heads on a slightly modified Sportster motor, with upswept dual pipes just like the XR750’s. And without question, the XR1000 was the fastest box-stock street Harley ever built. But it still was a Sportster and not an XR750; and it wasn’t all that fast compared to the competition. And those factors, in conjunction with its hefty, $7000 pricetag, insured that XR1000 sales would be few and far between.

For 1985, the XR1000 is still included in Harley’s 13-model lineup; but the company seems to have concluded that trying to sell Sportsters as performance machines these days is a waste of time and money. Instead, the strategy now is to enhance the virtues that Harleys have always been alleged to possess-simplicity, reliability, quality, value, tradition, and a character that is unique in all of motorcycling.

There is strong evidence of that new philosophy in the two most recent Sportster models. The XLX-61, introduced late in 1982, isa no-frills, back-to-basics bike that has achieved half-decent sales success by emulating the classic Sportster look of the Fifties and Sixties. And the very newest Sportster, the 1986 V: Evolution model, takes that concept even further. Not only is it styled exactly like the XLX-61, but it reverts back to the Sportster’s original 883cc displacement. It also incorporates engine refinements that improve just about every conceivable aspect of the motor—except its performance.

Still, it's easy to be critical of the Sportster these days; it’s easy to call it anachronistic and atavistic and a bunch of other multisyllabic adjectives that allude to its decidedly unmodern character. But there's one truly impressive fact that can’t be overlooked: The Sportster is a survivor. After 28 years on the job. it’s still hanging in there.

You can count on a couple of fingers all the other motorcycles that can make a similar claim. Obviously, despite all of the Sportster's wrongs, there is something about it that is very, very right. ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

August 1985 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

August 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1985 -

Roundup

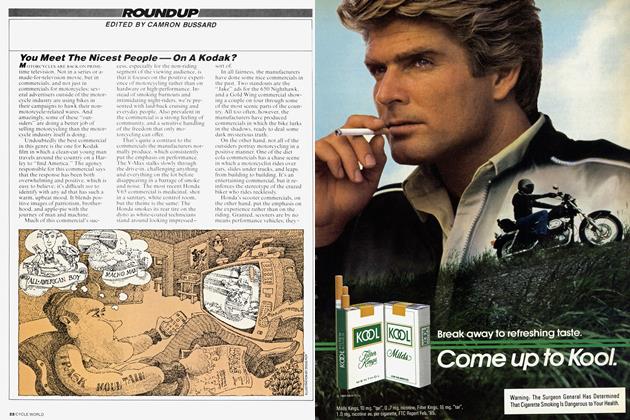

RoundupYou Meet the Nicest People—On A Kodak?

August 1985 By Camron Bussard -

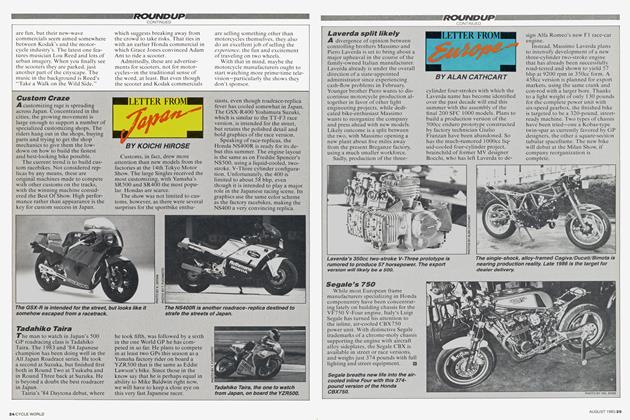

Roundup

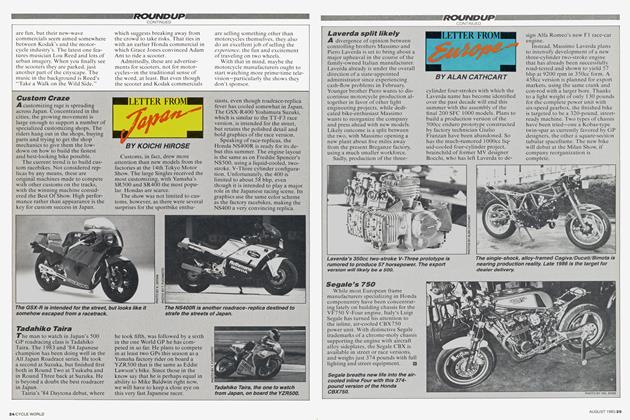

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

August 1985 By Alan Cathcart