What If?

EDITORIAL

IT'S BEEN ALMOST 20 YEARS SINCE someone made The Great Decision.

That someone was definitely a Japanese. assuredly a high-roller in the Honda organization, maybe even Mr. Honda his own self. And all he did was launch the development of something the rest of the motorcycling world had deemed either impractical or impossible: a four-cylinder motorcycle for the masses. A few years later, that motorcycle, the 1 969 Honda CB750 Four, became reality.

As far as decisions are concerned, that one was pretty high on the Mo mentous scale. The person who made it may have suspected the long-term implications of his actions, or per haps he hadn't a clue: either way, the future of the motorcycle was forever altered. In less than a decade, inline Fours all but became motorcycling.

But what if?

What if that decision had never been made? What if the Japanese manufacturers had concluded-ei ther independently or collectivelythat the world did fbi want four-cyl inder motorcycles? What if that first CB750 Four had never existed?

There are no absolute answers to those questions. But there are count less speculative ones. And one of the more logical of those is that a lot of truly great inline-Four motorcycles, not just that first 750 Honda, would never have existed. We wouldn't have known such legends as the first true superbike, the Kawasaki Z1 the crown-jewel inline-Four of the midSeventies, the CB400F; the amaz ingly competent GS1000/GSL 100 Suzukis: the fearsome 900 Ninja: the Bimota-inspired FJ 1100 Yamaha. to name just a few. No doubt, we would have had great motorcycles nonethe less, but they would have been differ en! great motorcycles. -

dkay, you sa~, but what kind of bikes would they have been?

Well, if the Japanese had not homed-in on the inline-Four, they probably would have refined the ex isting engine designs of the era (verti cal Twins, mostly. with a few V Twins, opposed-Twins and Singles) by making them the benefactors of their world-renowned technological skills. It's reasonable to assume, then, that these types of engines would have evolved into the most sophisti cated, reliable, performance-inten sive examples of their kind, and that today. we'd have mega-tech Twins that would perform almost as well as modern multis-maybe even better in some ways.

It's easy to be repulsed by such a notion, to believe that if four-cylin der motorcycles had never happened, we'd be chuffing around today on a motley assortment of two-cylinder bikes about as exciting as a solitaire tournament in a rest home. After all, most of the Twins the Japanese have built so far have been rather. er, underwhelming. Yamaha's durable but uninspiring XS650 Twin: Kawa saki's absurdly overweight, ridicu lously underpowered KZ750 Twin: Yamaha's mechanically troubled XS750 and XS500 Twins: Suzuki's Tempter 650. Even the V-Twins that are so popular today aren't what you would call white-hot performers.

But those bikes help prove the very point I'm trying to make: These ma chines and others like them have not consistently been the main focus of the engineering efforts put forth by the Japanese. They haven't been per formance flagships. bikes on which the future of their companies-and, to a certain extent, the future of the industry-rested. Instead, they were given second-class status.

But. . . if the same amount of time, money and brainpower had been spent on the development of Twins as on inline-Fours: if the UJM of the Seventies had been the vertical-Twin or the V-Twin: you can bet your sweet Aspencade that we'd now have some Twins that would boggle the mind. We assuredly wouldn't have the 100-plus horsepower that is man datory on today's four-cylinder mo tors: but we would have 70-, 80-, maybe even 90-horsepower Twins that could perform almost as well as modern Fours. Why? They would weigh considerably less, which would allow them power-to-weight ratios comparable to those of the four-cyl inder performance bikes.

Yamaha's state-of-the-art FZ750, for example. is a 100-horsepower Four that weighs 500 pounds~ to have the same power-to-weight ratio with a 1 70-pound rider aboard, a 750 Twin that weighed 350 pounds (not at all an unreasonable expectation) would need just 77 horsepower (also quite reasonable). And the Twin would be superior in most other ways. It would be lighter, lower, narrower and, un doubtedly, better-handling, as well as torquier and more fuel-efficient. All in all, it would offer performance that most riders could use and appreciate most of the time

If you have doubts about all this, think about the state of motorcycle design 25 years ago. before the Japa nese got involved. Fours were consid ered not feasible, two-strokes were a bad joke, and motorcycles in general were colossally unreliable, despite being far simpler than they are today. But the Japanese changed all that. Most of the basic ideas they em ployed to elevate the technologies had already been invented, but they made those ideas work-usually far better than anyone, including the in ventors of the ideas, ever imagined.

All this is academic, I kn~w, be cause sooner or later, someoneprobably one of the Japanese compa nies-would have built an inline Four anyway. It wouldn't have hap pened as soon as the actual event did, and it would have spawned a differ ent generation of Fours than the one we knew. But eventually, it would have happened.

Still, the idea of two-cylinder mo torcycles being the dominant force in the sport today isn't as far-fetched as it may seem. If someone hadn't made that one decision nearly 20 years ago, thingsjust might have turned out that

way.

Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Sale of the Century

November 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

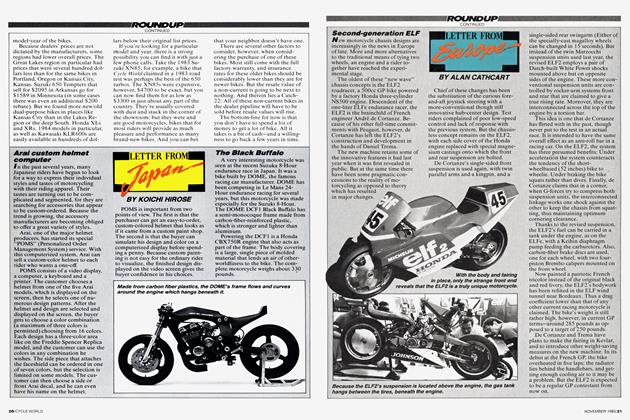

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

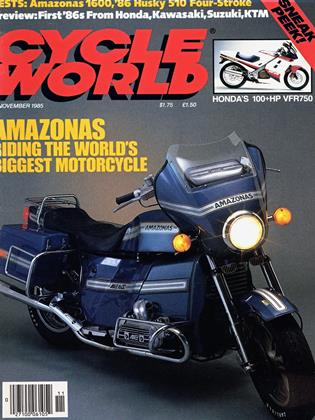

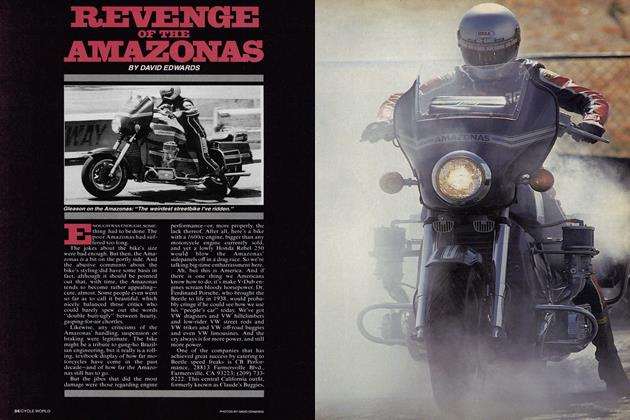

FeaturesRevenge of the Amazonas

November 1985 By David Edwards -

Features

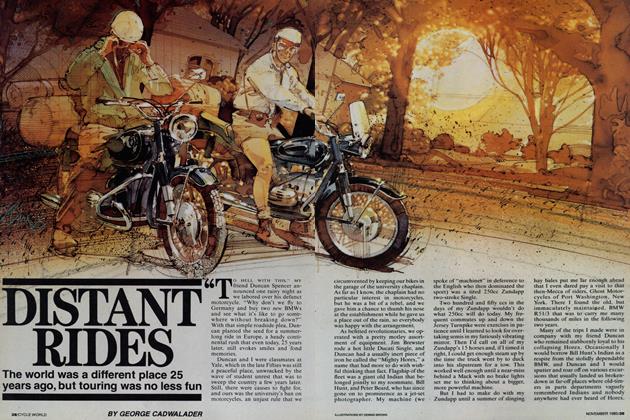

FeaturesDistant Rides

November 1985 By George Cadwalader