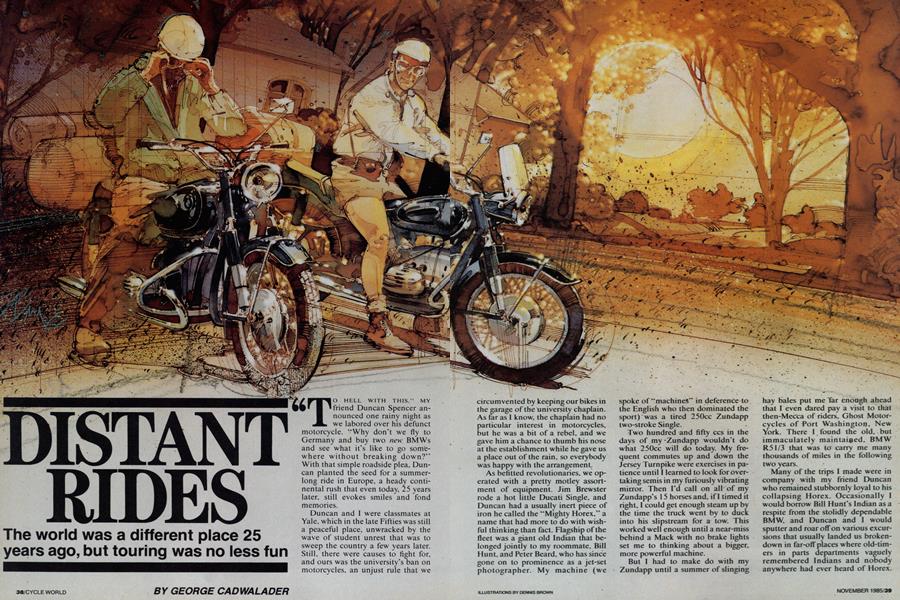

DISTANT RIDES

The world was a different place 25 years ago, but touring was no less fun

GEORGE CADWALADER

"TO HELL WITH THIS." MY friend Duncan Spencer announced one rainy night as we labored over his defunct motorcycle. "Why don't we fly to Germany and buy two new BMWs and see what it's like to go somewhere without breaking down?" With that simple roadside plea, Duncan planted the seed for a summerlong ride in Europe, a heady continental rush that even today, 25 years later, still evokes smiles and fond memories.

Duncan and I were classmates at Yale, which in the late Fifties was still a peaceful place. unwracked by the wave of student unrest that was to sweep the country a few years later. Still, there were causes to fight for, and ours was the university's ban on motorcycles, an unjust rule that we circumvented by keeping our bikes in the garage of the `university chaplain. As far as I know, the chaplain had no particular interest in motorcycles. but he was a bit of a rebel, and we gave him a chance to thumb his nose at the establishment while he gave us a place out of the rain, so eveiybody was happy with the arrangemenL

As befitted revolutionaries, we op erated with a pretty motley assort ment of equipment. Jim Brewster rode a hot little Ducati Single. and Duncan had a usually inert piece of iron he called the `Mighty Horex,' a name that had more to do with wish ful thinking than fact. flagship of the fleet was a giant old Indian that be longed jointly to my roommate. Bill Hunt. and Peter Beard, who has since gone on to prominence as a jet-set photographer. My machine (we spoke of "machines" in deference~to~, the English who then dominated the sport) was a tired 250cc Zufldapp two-stroke Single. -T'....-.. k.

Two hundrt~l and fifty ccs in the days of my Zundapp wouldn't do what 250cc will do today. My fre quent commutes up and down the Jersey Turnpike were exercises in pa tience until I learned to look for over taking semis in my furiously vibrating mirror. Then I'd call on all~~ of my Zundapp's 15 horses and, if I timed it right, I could get enough steam up by the time the truck went by to duck into his slipstream for a tow. This worked well enough until a near-miss behind a Mack with no brake lights set me to thinking about a bigger, more powerful machine. -

BuI I had to make do with my Zundapp until a summer of slinging hay bales put me Tar enough ahead that I even dared pay a visit to that then-Mec~ca of riders, Ghost Motor cycles of Port Washingtoi. New York. There I found the old. but immaculately maintai~ed, BMW R5 113 that was t~ cany me many thousands of miles in the following tWo years.

Many of the trips I made were in company with my friend Duncan who remained stubbornly loyal to his collapsing Horex. Occasionally I would borrow Bill Hunt's Indian as a respite from the stolidly dependable BMW. and Duncan and I would sputter and roar oft' on various excur sions that usually landed us brokendown in far-off places where old-tim ers in parts departments vaguely remembered Indians and nobody anywhere had ever heard of Horex.

After a year or so of these increas ingly frequent unscheduled stops, Duncan's patience with the Horex fi nally began to wear thin, and he ut tered the words that would send us to Europe for two brand-spanking-new BMWs. The only problem was that I had signed up for a previous engage ment that summer. Luckily, the Pow ers in Washington, D.C., decided that the Russians could be held in check without my help until the fol lowing September when I was to re port for duty in the Marine Corps.

Butler & Smith, BMW's United States agent at that time, arranged for us to pick up two new R50s at the factory in Munich for what I recall was $600 each, payable in New York, while an obscure airline coMtracted to fly us to England and back for an other $300 each. This didn't leave us with a whole lot of cash to eat with, but we figured we'd make out all right if we camped whenever we could.

Upon our arrival in Munich, we were met by a politely efficient BMW representative who showed us through the newly built plant where motorcycles and sports sedans rolled off modern assembly lines with Prus sian precision. But behind this monu ment to Germany's industrial rebirth there stood a group of ramshackle wood-frame buildings in which craftsmen continued to build mag nificent BMW limousines just as they had always done, entirely by hand. It was plain enough, even to a skeptic like Duncan, that the company's commitment to high quality was not simply an advertising slogan.

This impression was confirmed when two uniformed attendants wheeled our already warmed-up bikes into the sunlight, inspected them one last time for microscopic imperfections, clicked their heels and departed. We departed as well, stop ping briefly at the nearby shop of the famous pre-war BMW factory rider, George Meier, before heading off for the lakeside town of Starnbergwhere, we were told, Munich's single girls went looking for excitement.

Sadly, instead of spending that night in the arms of maidens, we spent it in a swamp. One of the pit falls of traveling through Bavaria is that every little village has an ancient inn, each one famous for its own brand of locally brewed, springhouse-cooled dark beer. By the time we had visited three or four of these establishments we were in no condi tion to go on. So we picked a place to camp, which in our beer-benumbed state looked pretty good but turned out to be a peat bog, dry on the sur face but wet enough beneath that we awoke the next morning to find our shiny new bikes sunk hub-deep in mud. An hour of furious effort got us back on the hardtop with the BMWs looking like veterans of an off-road rally-and their hung-over owners looking even worse.

For breakfast that morning we pulled into a little mountain Gasthaus, where crowds of friendly Bavarians gathered to admire with possessive pride the still-novel sight of post-war-model BMWs on Ger man roads. The inn's portly propri etor ushered us with much bowing and scraping into his cool, dark din ing room where we had to duck to avoid the huge sausages that hung from smoke-blackened beams. We sat by an open window listening to the sounds of a solitary woodchopper working in the hills beyond, and in due course our host reappeared, stag gering under the weight of a ham and cheese omelet that must have taxed the resources of every farm in the vil lage. This monstrous production, ac companied by jelly-slathered slabs of homemade bread and great, steaming mugs of coffee, banished what little of our hangovers we hadn't already sweated during our earlier escape from the swamp.

We went on to Starnberg in high spirits. There, the first person we met was a beautiful schoolteacher who would not be happy until she had been given a ride on a BMW. But be cause there was only one of her and two of us, we asked if she might not have an equally beautiful friend who was also pining for a ride. She al lowed as how she did-"a blonde, very pretty. yah?" So while she went off to fetch this enchantress, Duncan and I argued over who was going to end up with whom. We had just re solved by the flip of a coin that I was to get the blonde, when our friend returned in company with a gargan tuan, ugly Brunhilde.

We s~t off for the beach, reflecting on the maxim that a girl will rarely produce a blind date prettier than herself. To make matters worse, the engineers at BMW had not planned for the kind of load I was carrying, so I ground a good deal of metal off my new mufflerson the rough stone road.

Once at the beach n~y giant com panion produced a vat of suntan lo tion and, through a pantomime of grunts and giggles, indicated that I was to smear this stuff all over her back. I was already sick enough over the destruction of my mufflers, and the prospect of this job, which would have been like painting a barn, was too much. I told Duncan I'd meet him in Vienna and fled. He caught up with me an hour later, his girl having abandoned him in annoyance over my precipitous departure.

continued on page 44

"Motorcycles;' he said, "are like children, yah? You gif zem all ze best, mid still sometimes zey go bad!"

In Venice, we rode around in gondolas and paid outrageous prices for beer.

continued from page 41

Our misfortunes in love were soon forgotten in the beauty of the country through which we were riding. We wound our way along twisting roads into the Alps, the bikes gasping a bit in the thinning air, and crossed over into Austria.

Duncan was not one to baby ma chinery. He flogged his bike hard right from the start, while I lagged way behind, dutifully following the break-in instructions to the letter. So it was all the more disappointing when, as we approached Vienna, my carefully maintained machine devel oped a howling bearing in the gear box. Duncan had suffered enough over the years at my unflattering comments about his Horex to have no pity. He ragged me unmercifully as we searched through the labyrin thian streets of Vienna's industrial section trying to find BMW's factoryauthorized mechanic. When at last we located this gentleman, we dis covered that to be a mechanic in Aus tria is a far higher calling than it is here. The Master, clad in a spotless white coat, would not condescend to touch my machine until his assistants had entirely purified it from dirt. Then, before the admiring eyes of his apprentices, he fastidiously set to work, replacing the offending bearing without getting even a spot of oil on his jacket. He was immensely proud of BMWs and took it as a personal blow to his pride that mine should have failed me. "It is like children, yah? You gifzem all ze best, und still sometimes zey go bad!"

Our stay in~Vienna passed in a happy haze of beer and Wiener Schnitzel. We would start each morning at the Cafe Mozart where, among the international collection of newspapers all carefully bound with split bamboo poles, we'd find the New York Times and read up on do mestic events that seemed very far away. Then, as often as not, we would go our separate ways, meeting again in the evening to resume our pursuitofthe ladies.

On one such day I set off by myself to find the Esterhazy Castle, where Haydn had been court composer. I got lost, as usual, and blundered in stead onto the Hungarian border, where for the first time I saw the Iron Curtain. It was just that: two rows of electrified barbed wire with a mine field between them stretching off as far as the eye could see in both direc lions. There was a crater in the mine field and shreds of clothing hanging from the wire. From what I could gather. a Hungarian family tried to get across a few nights before. Only the son survived the mine explosion, and the Austrian authorities sent him back to his remaining relatives in Hungary. In retrospect. I think that particular day had a lot to do with my later decision to make a career of the Marine Corps.

Leaving Vienna, bound for Italy via Salzburg, Innsbruck and the Brenner Pass, we rode through the fa mous Vienna Woods and stopped in a wheat field to wait out a rain squall. While we watched from beneath a grove of pines, the sun broke through the clouds, flooding the fields below us with a golden light that was made all the more vivid by the rain shrouded forest beyond. We stood. spellbound, as the sun came and went from behind wind-driven clouds, sending shimmering waves of light chasing shadows across the wheat, and witnessed the most beau tiful moments of the summer.

The Brenner Pass provided an in teresting contrast between precise Austrian bureaucrats on one side of the frontier and cheerful, bumbling Italian functionaries on the other. Once in Italy. however, we were re ceived with surly scowls until we dis covered that with our blond hair and BMW motorcycles, we were being mistaken for Germans. The memory of World War II was still very much alive in that part of the world, and there was plainly no love lost be tween the two former allies. Duncan somehow conjured up an American flag. which solved our problem.

Our first planned st~p in Italy was Venice. There, as expected of tour ists, we rode around in gondolas and paid outrageous prices for beer. But after the simple friendliness we had found in Austria, we felt uncomfort able enough in touristoriented Ven ice to cut short our stay and head in land for Padua and Veronna. In one of those ancient towns, I can no longer remember which, we went to an outdoor performance of Aida given in a still-intact Roman coli seum. Cpera in Italy has none of the highbrow pretensions of the Metro politan. For one thing, the audience can understand the words, so if a singer blows his lines, as often hap pened that night. there are hoots and jeers until the unfortunate performer starts over and gets it right. Vendors circulated through the stands, and at one point a tired old elephant that had been pressed into service from the local zoo for the Grand March disgraced itself on center stage. The crowd went wild while the chorus of Egyptian soldiers downed swords and upped shovels to clear away the steaming mountain.

Durin~ intermission, Duncan's in judicious remarks to a senora led to our being surrounded by an angry mob of hot-blooded gentlemen, all bent on defending the honor of the offended lady. After an uneasy cou ple of minutes it became plain enough that nobody really wanted to fight. Nonetheless, it seemed prudent not to stick around, so we climbed on the bikes and left as quietly as was possible, in view of the holes Brunhilde had worn in my mufflers.

to Ravenna and then south along the Adriatic coast. We had by this time picked up another American, Gor don Fairburn, who was traveling through Europe with his guitar at a time before every American tourist carried a guitar. Gordon's singing earned us a lot of free meals. My sing ing did, too, although in my case, I'm sure that anguished music-lovers fed us in the hopes that I would eat rather than sing.

For lunch we usually had a loaf of bread, a hunk of cheese and a bottle of wine. I would eat most of the bread and cheese while Duncan and Gor don would drink most of the wine. Thus, Duncan's riding in the after noon was sometimes a little shaky. Once, I was following him down a perfectly straight country road when, for no apparent reason, he, Gordon and the guitar shot off into a field of potatoes. I watched amazed as they churned along for some distance, throwing up a great roostertail of dirt and potatoes, before coming to rest unhurt but upside-down in a ditch.

This was one we couldn't fix. Dun can's headlight was squashed, short ing out the entire electrical system, and both carbs had inhaled buckets ful of mud. A crowd gathered from nowhere. Somebody produced a frayed piece of line that we had to buy at huge cost, and we set off again with Duncan in tow. We finally found a mechanic capable ofjury-rig ging a repair. then headed across the Appenine Mountains for Rome with a chastened Duncan swearing off the bottle as I have heard him do many times since.

Coming down the switchback roads off the Appenines. I practiced the art of countersteering through curves well enough to make for one of the fastest rides of my life. It was one of those unforgettable days when

my bike and I became "one single moving part." The R50's accelera tion was modest on flat ground, but more than adequate when assisted by gravity and a steep hill. With the folly of youth. I raced into each descend ing turn, leaning hard on the inboard handlebar to pitch the bike onto its ear, and ground my way around the corner in a shower of sparks. By rac ing standards, I don't suppose I was going all that fast, but in my mind's eye I saw myself flashing by Meier and Surtees and all the other Great Men of the age.

Instead. I flashed by a policeman tooling along on his bright red Moto Guzzi. "I've had it now," I thought, while hitting the brakes. Sure enough, I looked back to see the Guzzi in hot pursuit, and I started to pull over, wondering how the Marine Corps would take the news that I was languishing in an Italian jail. Instead, my mustachioed pursuer shot by, shouting "Avanti!" or whatever it is Italians shout when they want to race. So together we tore down the mountain, trading the lead back and forth as we went. At the bottom my opponent became once again a po liceman and lectured me against speeding. I agreed to mend my ways, and he saluted solemnly before going off to resume his duties.

Approaching Rome we learned with chattering teeth that Caesar had not anticipated motorcycles when he paved his roads with cobblestones. In the city, we reverted once again to the uncomfortable role of tourists. At the Vatican we ran into some American girls we had earlier camped with on a moonlit Adriatic beach, but the stern presence of the Pope so stiffened their resolve against any additional lapses of virtue that we had no further comfort from that quarter. So we headed off for Pisa to climb the Lean ing Tower in the company of a herd of urchins all trying to sell us souve nirs. There was no escape from these persistent entrepreneurs except through flight. So we rode back into the country. resolving over dinner to visit no more big cities until we ar rived in France.

That night it rained. Our usual foul-weather plan when camping was to park the two bikes side-by-side and stretch a tarp between them to serve as a tent. We got this contrivance rigged just ahead of the downpour and were soon asleep beneath it. But as the night wore on, the tarp filled with enough water to tip the bikes over, Duncan's on him and mine on me. In our besotted state, we thought we were being attacked. Our frantic

struggles to get out from under our assailants only served to dump the re maining contents of the tarps on our heads. "Succuro!," bellowed Dun can. "The bastards are trying to drown us." Whereupon with the strength of desperation he hurled his machine clear and jumped to his feet. About this time I also got free from my bike and staggered upright, still under the tarp. Duncan spotted this strange, shrouded apparition and threw himself on what he took to be our attacker. It was my turn to holler "Succuro" as I floundered around, engulfed in canvas with Duncan flail ing away outside. .

By the time we got all this sorted out it was impossible to get back to sleep. so we rode all through the soggy night headed for what we hoped would be the flesh pots of the Italian Riviera. Instead, dawn re vealed worn and dirty beaches, some how looking all the more squalid in their early-morning emptiness. Dis gusted. we turned northwest, back to ward the mountains and the French frontier. At the border town of Cottiennes we were tempted to linger by two beguiling sisters named Petri, but the summer was getting on and all of France, England and Scotland still lay ahead.

At the bottom of the hill, my opponent became once again a policeman.

The tarp filled with enough water to tip the bikes over, and in our beer-besotted state we thought we were being attacked.

The long ride across the high, roll ing hills of France's lovely Massif Central was one of the best of the summer. Today, the names on the map conjure up memories of magnifi cent meals-roast rabbit in Valence, truly memorable pastries in Le Puy, unforgettable wine everywhere. In Périgueux we ran afoul of les gen

darines mounted on massive, pre war, flathead BMWs, but all ended well thanks to our mutual admiration for those machines. Then it was on to Bordeaux to stay with two splendid octogenarian ladies whose days were spent ministering to the elderly of their village, most of whom were 20 years younger than they were.

Wecross~d the English Channel at Cherbourg. First we went to Oxford, where Duncan was later to return as a student, and then into the English countryside. Riding on what for us was the wrong side of the road proved

a bit of a trick, particularly at inter sections, where we invariably looked left before proceeding into the path of furiously honking traffic.

In Scotland, the i~tnd of enchanted names, there were the towns of Ecclefechan, Lockerbie, Lesmahgow and then Glasgow, from whence Duncan's grandfather had left to seek his fortune in the New World. From Glasgow we continued north along the shore of Loch Lomond until Dun can hit wet oil and skidded into a pond. I was far enough behind to watch all this and was laughing so hard at the sight of him sitting discon solately tank-deep in water that I hit the same patch and ended up right beside him. We drained everything, changed the oil in nearby Arrochar and .were off again, the bulletproof BMWs apparently none the worse for their dunking.

The roaJ from Arrochar led through Crianlarich and Daimally to Oban where we rode with a boatload of sheep across the Firth of Lorn to the Isle of Mull. Duncan had stayed on Mull as a boy. His old friend Neal the Gamekeeper still lived in the same thatch-roof cottage, surrounded by the guns and fly rods that were the tools of his trade. Neal walked with a limp he had picked up as a dispatch rider for the British in North Africa. As he told the story, days of artillery fire had so stirred up the desert sand that the only way he could find his way between positions was to ioop the wire that ran between command posts over his footpeg and follow it blindly to his destination. This tech nique worked well enough until one day he met another rider doing the same thing from the opposite direc tion. The resulting crash put him out of the war.

Hanging over us like a dark cloud was the knowledge that time was runfling out for our European odyssey. I had to get to Quantico and Duncan back to Yale. With the sense that something never to be repeated was about to end, we rode back to Glas gow where we arranged to have the bikes shipped home before flying out for New York.

I kept that old R50 until a mine explosion in Viet Nam ended my Ma rine Corps career and, I thought, my career as a motorcyclist as well. But a couple of years ago I succumbed to nostalgia and bought another BMW. I don't ride it much, but when I do I always look in my mirror for that po liceman's red Moto Guzzi, and I think back on distant rides when the whole world still seemed to lie along the road ahead.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialWhat If?

November 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Sale of the Century

November 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1985 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

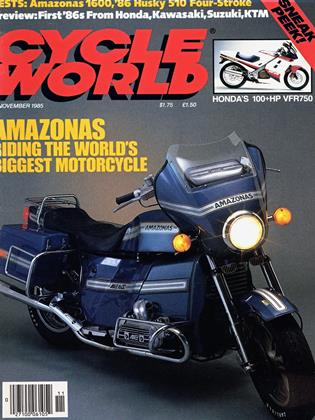

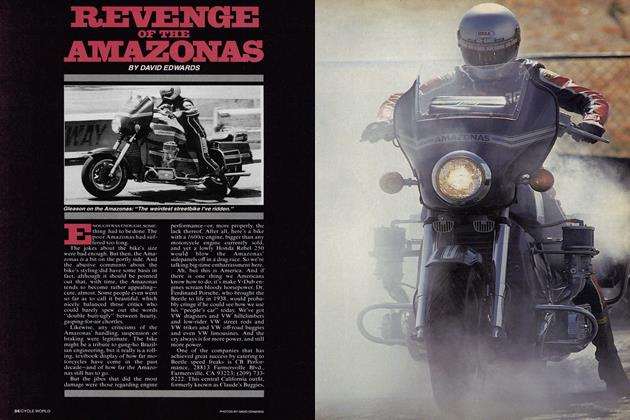

FeaturesRevenge of the Amazonas

November 1985 By David Edwards