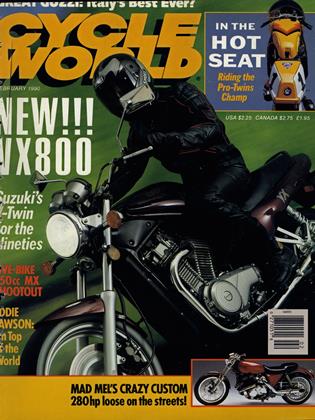

KILLER GOOSE

Moto Guzzi to Ducati: "We'll see your 851 Sport, and raise you one Dr. John's Replica."

ALAN CATHCART

THE WORST OF THE RUMORS INsisted that Moto Guzzi, that venerable Italian company, maker of quirky, affable V-Twins so loved that their owners affectionately refer to the bikes as “Gooses,” was in danger of going out of business.

Evidence was out there for all to see. After all, hadn't Moto Guzzi's worldwide sales dropped to a mere 5900, compared to no less than 14,300 back in 1980? And Alejandro De Tomaso, the automotive tycoon who owns Guzzi, had just sold a 70-percent interest in sister-company Benelli to outside investors; surely he wanted to unload Guzzi, as well.

Apparently, the rumormongers neglected to ask De Tomaso about the speculation. I did just that.

“I can positively state that this (the sale of Moto Guzzi) is not the case.” De Tomaso told me when we met at his opulent Hotel Canalgrande headquarters in Modena just a couple of days before the Milan Motorcycle Show opening. “On the contrary, we are re-investing the major part of the proceeds from the Benelli sale (totalling about $10 million) in new machinery and technology for Moto Guzzi. We intend to base the future development of the Guzzi marque on the lesson provided by Harley-Davidson’s success in recent years. They have developed new models incorporating up-to-date technology, but in the traditional style of their previous range. I am certain this is the correct road for Guzzi. and the first fruits are being shown at Milan.”

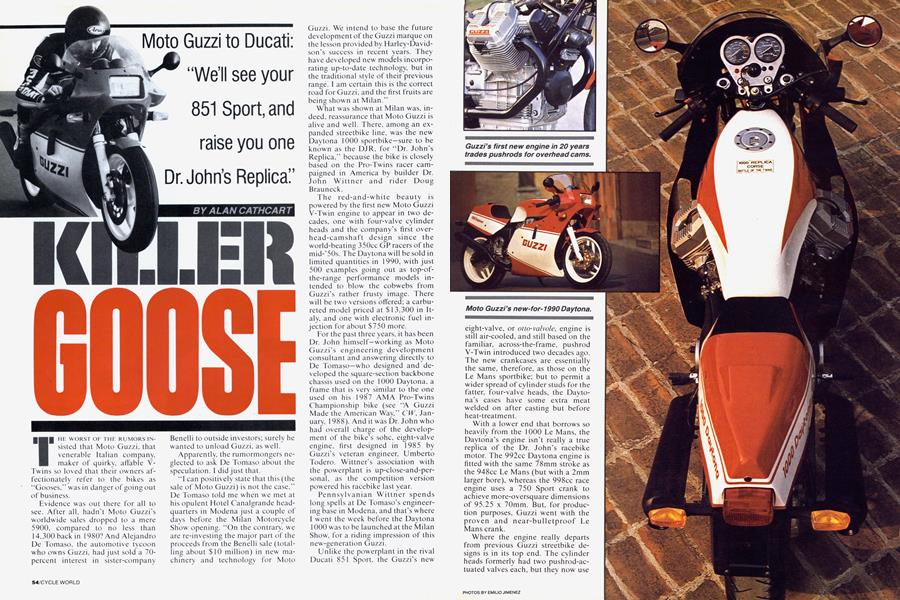

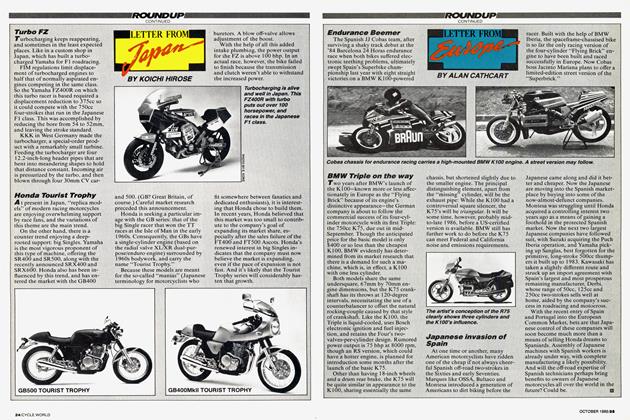

What was shown at Milan was, indeed. reassurance that Moto Guzzi is alive and well. There, among an expanded streetbike line, was the new Daytona 1000 sportbike—sure to be known as the DJR, for “Dr. John's Replica,” because the bike is closely based on the Pro-Twins racer campaigned in America by builder Dr. John Wittner and rider Doug Brauneck.

The red-and-white beauty is powered by the first new Moto Guzzi V-Twin engine to appear in two decades, one with four-valve cylinder heads and the company’s first overhead-camshaft design since the world-beating 350cc GP racers of the mid-’50s. The Daytona will be sold in limited quantities in 1990, with just 500 examples going out as top-ofthe-range performance models intended to blow the cobwebs from Guzzi's rather frusty image. There will be two versions offered; a carbureted model priced at $13,300 in Italy, and one with electronic fuel injection for about $750 more.

For the past three years, it has been Dr. John himself—working as Moto Guzzi’s engineering development consultant and answering directly to De Tomaso—who designed and developed the square-section backbone chassis used on the 1000 Daytona, a frame that is very similar to the one used on his 1987 AMA Pro-Twins Championship bike (see “A Guzzi Made the American Way,” Of, January, 1 988). And it was Dr. John who had overall charge of the development of the bike's sohc, eight-valve engine, first designed in 1985 by Guzzi’s veteran engineer, Umberto Todero. Winner's association with the powerplant is up-close-and-personal, as the competition version powered his racebike last year.

Pennsylvanian Wittner spends long spells at De Tomaso’s engineering base in Modena, and that’s where I went the week before the Daytona 1000 was to be launched at the Milan Show, for a riding impression of this new-generation Guzzi.

Unlike the powerplant in the rival Ducati 851 Sport, the Guzzi's new eight-valve, or otto-valvole, engine is still air-cooled, and still based on the familiar, across-the-frame, pushrod V-Twin introduced two decades ago. The new crankcases are essentially the same, therefore, as those on the Le Mans sportbike; but to permit a wider spread of cylinder studs for the fatter, four-valve heads, the Daytona’s cases have some extra meat welded on after casting but before heat-treatment.

With a lower end that borrows so heavily from the 1000 Le Mans, the Daytona’s engine isn’t really a true replica of the Dr. John’s racebike motor. The 992cc Daytona engine is fitted with the same 78mm stroke as the 948cc Le Mans (but with a 2mm larger bore), whereas the 998cc race engine uses a 750 Sport crank to achieve more-oversquare dimensions of 95.25 x 70mm. But, for production purposes, Guzzi went with the proven and near-bulletproof Le Mans crank.

Where the engine really departs from previous Guzzi streetbike designs is in its top end. The cylinder heads formerly had two pushrod-actuated valves each, but they now use four valves actuated by a single overhead cam atop each cylinder.

EMILIO JIMENEZ

That conversion has been accomplished with surprising simplicity. The component that was the camshaft on the pushrod motor has been turned into a jackshaft that drives two 19mm-wide. toothed rubber belts at the front of the engine. A belt extends up the front of each cylinder to a pulley attached to the end of each head's single camshaft. At right angles to the camshaft are two long rocker arms that serve as cam followers, with a fork on each rocker that opens the paired valves in each cylinder.

This layout is unusual in that the cam is not perched atop the head like on most other overhead-cam designs; instead, the cam lies alongside and inboard of the exhaust port, an arrangement which avoided the need to make an already tall engine even taller. The Daytona engine also is only 1.5 inches wider than the pushrod version, mostly because of the fatter valve covers needed to enclose the extra valve gear of the fourvalve heads.

But while the Daytona's cams are not truly located “over" the heads, this is an ohc engine nonetheless, since the cams are entirely located above the combustion chambers and use only rockers, no pushrods. All the same, the mass of the rockers does have a limiting effect on maximum engine speed. Indeed, Wittner had to limit the rev ceiling on his race engines to less than five figures for reliability purposes, and he has allowed an extra margin of safety on the road version by limiting revs to 8000 rpm.

Even w ith that rev limit, the 40mm Dell'Orto-equipped Daytona engine is said to produce 91 horsepower at the crank, at 7800 rpm. The model fitted with Weber/Marelli electronic fuel injection benefits from a 3horsepower increase and a considerable improvement in acceleration, according to Wittner. And it won't be afflicted with the stiff throttle pull of the be-carbed prototype I rode.

Straining those throttle cables to their limit and taking advantage of the DJR’s gearbox—identical to the Le Mans unit except for a taller fifth gear—I managed to redline the prototype on an Italian autostrada, which gave a speedometer-indicated 145 miles per hour, about 20 miles an hour faster than the Le Mans 1000 that Cycle World road-tested in 1988. Riders in search of more speed will be interested to know' that the ELI model can be persuaded to give 100 horsepower at the crank simply by exchanging the silencers for a pair of freer-flowing units, and by fitting new velocity stacks and a different computer chip to the fuel-injection system. Wittner reckons 160 miles per hour in street form will be readily attainable.

To really appreciate how' good this new Guzzi is, though, you don’t need a radar gun or a long, straight ribbon of asphalt: All you have to do is roll open the throttle. With a whopping 66.5 foot-pounds of torque available at 5400 rpm, this thing pulls like a big steam locomotive, and keeps on pulling right into an impressive top-end punch, underlined by The Sound, a lovely, syncopated thunder from the twin black exhaust pipes.

Below’ 5000 rpm, the Daytona feels rather lumpy and not very civilized. There’s quite a lot of vibration low down in the rev range, especially if you let the motor lug, and it’s only when the tach needle hits 5000 that the engine really smooths out and starts to deliver that massive midrange wallop. From there up to the 8000-rpm redline, there's turbinelike performance of a twin-cylinder kind only Ducatis could hitherto provide. And the Daytona’s top-gear roll-ons make even a Ducati 85l’s look puny in comparison. Wind the throttle on hard, and the Guzzi fairly leaps forward, even w hen speeds are over 100 miles per hour.

This kind of performance makes use of the five-speed gearbox almost redundant, which is just as well since it's only a slight improvement on existing Guzzi gearboxes, and is still rather clunky and harsh despite the 4.5-pound-lighter flywheel Wittner has specified to help smooth out gear changes. However, this modification has dramatically reduced the gyroscopic effect that is unavoidably present in a motor with a lengthways crankshaft. Sure, when you whip in the clutch at a stop and rev the motor, the bike torques sideways, but in normal use, you honestly don't notice it. There’s no understeer when you shut the throttle, no sense of having to fight the crank's gyro action when you lay the bike into a turn.

Similar'y, shaft-drive torque reaction is absent on the DJR, due to Wittner’s floating rear gearcase and parallelogram set-up. This is the same system that’s been fitted to his racers for the past three years, and means there’s no chassis rise and fall as you change gears, no rear-end judder when the throttle is chopped going into a corner. In fact, the bike's neutral, predictable handling could easily fool you into thinking you were riding a chain-drive, transversecrank Twin rather than a longitudinal shaftie.

The suspension, too, performs impressively. certainly not in the way normally associated with big Guzzis, w hich have generally been rather unwieldy, especially over rough surfaces. The single, no-linkage Koni shock absorber on the DJR just soaks up bumps and ripples that would have the rider propelled skywards out of his seat on a conventional, twinshock Guzzi. Up front is an MIR Marzocchi fork with 5.5 inches of travel. The fork works well—better than the Marzocchi unit on the Ducati 851—due in no small part to its special dual-rate springs. The crossover point between the two spring rates has been carefully calculated. though apparently the most-effective practical tests involved sending lightweight Doug Brauneck out to ride over as many cobblestones and tram lines as he could find with a 66-pound sack of sand tied around his w'aist to simulate the suspension requirements of a typical Guzzi customer. Not a high-tech technique, but effective.

The performance of the disc front brakes— Brembos featuring new-design rotors and the latest-generation four-piston calipers—is noteworthy. In fact, they were so effective that I was convinced that squeezing the front-brake lever was operating the rear disc, as well, just as on the linked, three-disc system that the Dr. John's racebike uses. Not so. “We know' that not everyone is a fan of the linked system.” said Wittner. “And we hope to sell this bike to people who maybe haven’t owned a Guzzi before, and who might be put off by linked brakes. So the Daytona has a conventional system, but we hope to offer the linked design as an option at no extra cost if the customer wants.”

With excellent handling, worldclass brakes and the phenomenal midrange performance of its new eight-valve engine, the Dr. John’s Replica is the greatest Guzzi yet. In the past. Moto Guzzi owners had to make excuses for their bikes' lack of power, lack of suspension and, yes, lack of sophistication. Not any more. Thanks to a recommitment from the factory and to the dedicated efforts of an American tuner who always believed in the bike, the Goose is flying again in the land of the high-performance superbike.

And it’s flying high. É3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

February 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

February 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1990 -

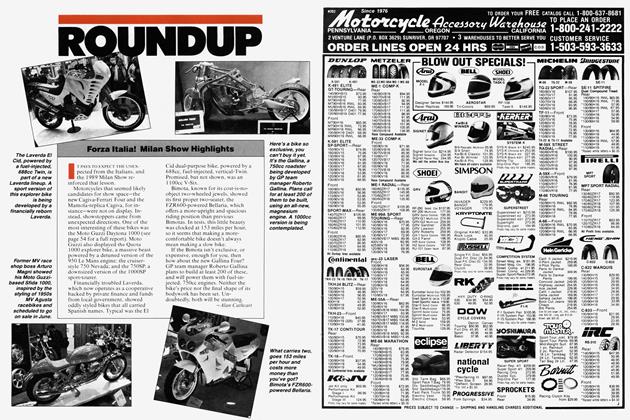

Roundup

RoundupForza Italia! Milan Show Highlights

February 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

Roundup1990 Ducatis, Husqvarnas: Don't Call 'em Cagivas Anymore

February 1990