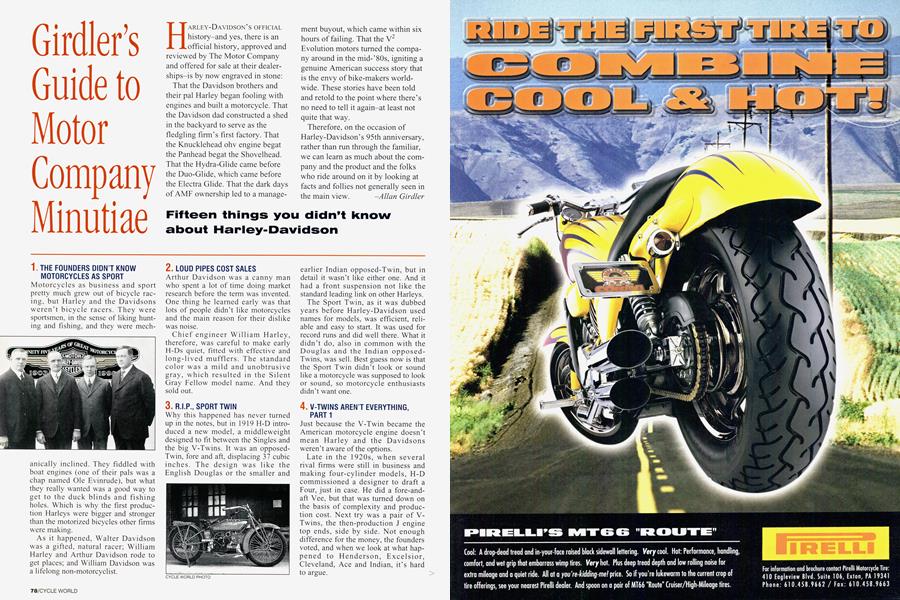

Girdler's Guide to Motor Company Minutiae

Fifteen things you didn't know about Harley-Davidson

HARLEY-DAVIDSON `S OFFICIAL history-and yes, there is an official history, approved and reviewed by The Motor Company and offered for sale at their dealerships-is by now engraved in stone:

That the Davidson brothers and their pal Harley began fooling with engines and built a motorcycle. That the Davidson dad constructed a shed in the backyard to serve as the fledgling firm's first factory. That the Knucklehead ohv engine begat the Panhead begat the Shovelhead. That the Hydra-Glide came before the Duo-Glide, which came before the Electra Glide. That the dark days of AMF ownership led to a management buyout, which came within six hours of failing. That the V2 Evolution motors turned the compa ny around in the mid-'80s, igniting a genuine American success story that is the envy of bike-makers world wide. These stories have been told and retold to the point where there's no need to tell it again-at least not quite that way.

Therefore, on the occasion of Harley-Davidson's 95th anniversary, rather than run through the familiar, we can learn as much about the com pany and the product and the folks who ride around on it by looking at facts and follies not generally seen in the main view.

Allan Girdler

1. THE FOUNDERS DIDN'T KNOW MOTORCYCLES AS SPORT

Motorcycles as business and sport pretty much grew out of bicycle rac ing, but Harley and the Davidsons weren't bicycle racers. They were sportsmen, in the sense of liking hunt ing and fishing, and they were mech anically inclined. They fiddled with boat engines (one of their pals was a chap named Ole Evinrude), but what they really wanted was a good way to get to the duck blinds and fishing holes. Which is why the first produc tion Harleys were bigger and stronger than the motorized bicycles other firms were making. --

As it happened, Walter Davidson was a gifted, natural racer; William Harley and Arthur Davidson rode to get places; and William Davidson was a lifelong non-motorcyclist.

2. LOUD PIPES COST SALES

Arthur Davidson was a canny man who spent a lot of time doing market research before the term was invented. One thing he learned early was that lots of people didn't like motorcycles and the main reason for their dislike was noise.

Chief engineer William Harley, therefore, was careful to make early H-Ds quiet, fitted with effective and long-lived mufflers. The standard color was a mild and unobtrusive gray, which resulted in the Silent Gray Fellow model name. And they sold out.

3. R.I.P., SPORT TWIN

Why this happened has never turned up in the notes, but in 1919 H-D intro duced a new model, a middleweight designed to fit between the Singles and the big V-Twins. It was an opposed Twin, fore and aft, displacing 37 cubic inches. The design was like the English Douglas or the smaller and earlier Indian opposed-Twin, but in detail it wasn't like either one. And it had a front suspension not like the standard leading link on other Harleys.

The Sport Twin, as it was dubbed years before Harley-Davidson used names for models, was efficient, reli able and easy to start. It was used for record runs and did well there. What it didn't do, also in common with the Douglas and the Indian opposed Twins, was sell. Best guess now is that the Sport Twin didn't look or sound like a motorcycle was supposed to look or sound, so motorcycle enthusiasts didn't want one.

4. V-TWINS AREN'T EVERYTHING, PART 1

Just because the V-Twin became the American motorcycle engine doesn't mean Harley and the Davidsons weren't aware of the options.

Late in the 1920s, when several rival firms were still in business and making four-cylinder models, H-D commissioned a designer to draft a Four, just in case. He did a fore-andaft Vee, but that was turned down on the basis of complexity and produc tion cost. Next try was a pair of V Twins, the then-production J engine top ends, side by side. Not enough difference for the money, the founders voted, and when we look at what hap pened to Henderson, Excelsior, Cleveland, Ace and Indian, it's hard to argue.

5. THE SECRET 750

Is this a prototype H-D, a sporting 750? The scene is the Juneau Avenue factory, 1931 or 1932. The engine is a DAH, a 750cc ohv V-Twin built for hiliclimbing in the late 1920s. But the frame, front end and brakes look like they come from the sidevalve R or D series 750s. The canister on the forks is a stock toolbox and the bike has a rear stand, items suited to road machines. The official word is that this is a road racer for Europe.. .but there was no 750 class in Europe then. Best guess has to be an experiment, a 45-cube high-per formance model canceled when the Depression brought motorcycle sales to a virtual halt.

6. STREAMLINING THAT DIDN'T

The ohv Model E, known quickly and ever since as the Knucklehead, was introduced in 1936 and Motor Comp any management wanted to make a splash with the sporting middleweight. They decided to do it by setting a national speed record, so they fitted a magneto and twin carbs to a new machine and cloaked it with spats for the fork tubes, discs on the wheels, a tiny semi-fairing up front and a full, tapered cowling out back. The first runs down Daytona Beach showed a serious lack of directional control. Rider Joe Petrali, who in 1935 won all, yes all, the national championship events, knew the wobble . came from the bodywork-aerodynamics were very much experi mental back then.

So they stripped off all the bodywork, juggled the gearing, and Petrali, who'd go on to be flight engineer aboard Howard Hughes' giant Hercules flying boat, tucked in, gritted his teeth and set a new national speed record, a two-way aver age of 136.183 mph. Then they put back the bodywork and the record machine was displayed in full regalia for years afterward, with lots of hemming and hawing if any body asked the wrong questions.

7. THE FEUD THAT FIZZLED

When upstart Al Crocker came out with a newer and more powerful 61inch V-Twin just after H-D introduced the Knucklehead, company engineers bought a Crocker and dismantled it, instructed to find some detail or feature Crocker had stolen from Harley Davidson. They failed.

8. HINT OF THINGS TO COME

The year is 1947, the scene is the Milwaukee State Fairgrounds and at first this looks like a Class C racer, an as-sold to-the-public WR. That's what the engine is, but look again: That's a clutch

lever and a double-downtube frame. Factory records call this a WRL, a designation that doesn't appear any where else in the H-D archives or literature. Hand clutch, foot shift and this style frame didn't officially appear until 1952, so this, as they say on the radio, was a test.

9. THE FACTORY FLAT-TRACKER THAT WASN'T

In 1969, Harley-Davidson announced a new racing machine, the XR-750, to be built for the 1969 season, when new AMA rules would permit 750s to run overhead valves. The factory announced the specifications and the model was duly declared legal.

Well, along comes one Bob Butler, an AMA privateer and apparently a pretty good shade-tree engineer. Our man Bob eyes the rulebook, asks a few well-placed questions, then proceeds to build his own XR by modifying a KR frame, then installing a Sportster 883 motor destroked from 3.8 to 3.2 inches-which is essentially the same thing the factory was about to do. Anyway, Butler enters some races and is in the process of dialing-in his home brewed XR when all of a sudden his bike gets yanked. Seems Milwaukee was behind schedule with their XR, sorry, but they'd be a year late. AMA approval was canceled, and Butler's XR-750 was outlawed.

But this was the first and only time a privateer ever had a factory bike before the factory did.

10. SUPER SPORTSTER

When the English and Japanese enlarged their Twins to 750cc and began making Triples and Fours, Harley-Davidson wondered if a high-tech Sportster might be needed. This is what they built, as a mock up only, in 1970. It has a frame that's a lot like the racing XR-750's, and the engine has a camshaft atop each cylinder head, while - the angle of the engine's Vee is 55 degrees, not the classic H-D 45. A neat and modern piece of work, but before it went into production man agement-types decided they could get as much bang for less buck by simply enlarging the ohv XL engine from 883 to 1000cc. So that's what they did.

11. V-TWINS AREN'T..., PART 2

In the 1960s, when Harley-Davidson's homegrown two-stroke Singles (Hum mer, Scat, Bobcat, etc.) proved more expensive and less advanced than the equivalents from Japan, H-D bought an Italian subsidiary, Aermacchi. That firm made excellent four-stroke run abouts, which proved better at perform ing than selling. In the `70s Aermacchi made world-class racebikes, but noth ing in the same league as Yamaha's dominant TZ750.

So Harley's lone racing engineer, Pieter Zyistra, drew up a really radical machine, a 750cc two-stroke Four. It was stacked, with four horizontal cylin ders in a square. Each cylinder had its own crankshaft, joined at an idler gear in the center. The design was up-to-date for 1975, with liquid-cooling, disc brakes and so forth. But it never got past the blueprint stage shown here. The financial side pointed out that winning world titles hadn't done Aermacchi all that much good, and that spending the money to make a competitive Harley for roadracing wouldn't be returned in sales or income.

Management listened to the finan cial side and not the sporting side, and this blueprint is as far as the RR-750 ever got.

12. UPGRADE THE XR!

More conventional (but just as discour aged by the accountants) was this upgrade for the XR-750. By swapping the ohv XR's four camshafts for a pair of gears, Zyistra hoped to use the existing cases and geartrain but with over head cams. (This isn't too different from what~Honda did with its RS750 dirt-track er.) Alas, the more cost-effective move turned out to be peti tioning the AMA to restrict the Honda, instead of improv ing the Harley.

13. V-TWINS AREN'T..., PART 3

After Honda's Gold Wing re-invented the touring bike and AMF took over Harley-Davidson, H-D hired Porsche, which did industrial design as well as sports and racing cars, to co-develop a model to rival Honda's Four.

The result was a liquid-cooled V Four, code-named Nova. The details are still locked in the vault, although blurry spy photos taken of tests at Talledega Speedway, and gossip picked up in the factory cafeteria, said the Nova worked. It was big and bulky, though, and didn't perform that much better than a Twin.

There was no official mention, but the Nova was shelved and the money and time transferred to the V2 project, the Evolution V-Twin that's with us, and doing well, still.

14. MORE ROADRACE TRIVIA

This is a seldom-seen production Harley-Davidson. The official classifi cation is RR-500, RR for roadracing and 500 because it's a 500cc two-stroke Twin. It was made by Aermacchi and was supposed to compete on a world wide basis, just as the earlier Aermacchi 350 had won a GP championship. In 1975 an RR-500 ran an American race as a Harley-Davidson but it broke down and rider Gary Scott said it wasn't competitive, so the program was abandoned, with the leftover engines going to Bimota.

15. IF IT WORKS, DON'T REPLACE IT

The parts of the 1998 V2 engine don't interchange with those of the Model E of 1936, even though the configura tion-45-degree V-Twin, ohv, two valves per cylinder, etc.-is the same. Even so, The Motor Company doesn't replace parts that don't need it.

A skim through the manual for the XR-750, still ruling flat-track after all these years, turns up a primary-cover gasket introduced in 1952, clutch springs from 1941, an engine-sprocket Woodruff key first used in 1936, and a spring to keep the oil tank in place that arrived with the DAH hillclimber in 1930.

W hy all these quirks? Because the people who made HarleyDavidson into a success, and kept it there through all the ups and downs human history is subject to, were people. They had ideas. Some worked, some didn't.

Before he created our companion publication Road & Track, the late John R. Bond was an engineer at Harley-Davidson. He was proud of having worked for The Motor Company, and he never lost his interest or enthusiasm for the prod uct. The first thing that struck him about Harley-Davidson, Bond used to say, was how many really inter esting and odd designs were hatched inside the walls of the Juneau Avenue plant.

And the second thing was how few of those different designs ever came out.

Contributing Editor Allan Gird/er has authored several books about The Motor Company, including Harley Davidson: The American Motorcycle, The Illustrated Harley-Davidson Buyers Guide and Harley Racers.