Inside the Accidental Fortress

AT LARGE

Encouraging words from the inner sanctum of insurance

SOME KINDS OF ENVELOPES YOU JUST don't want to open. Anything from the Federal Government fits this category, as do most missives from law offices. But the kind of envelope that I've come to dread most is the one from an insurance company.

This is not as irrational as it seems. Except for the time in 1964 when my Yamaha YDS2 went wheels-up on the invisible automatic transmission fluid some kind soul had neatly deposited on the tight lefthander behind the laundry where I worked after school, I have never made a claim on my bike insurors. Never. (Not that I haven’t crashed, but usually the deductible has been so big that it’s been easier just to replace the bent bits myself.) So I know that when an envelope comes from one of them, it can only be bad news, not a check.

I held the most recent one in my hands last December and just stared at it a while. It was from Criterion Insurance Company, a subsidiary of GEICO. As I looked at it, the history of my relationship with the company flashed through my memory like a fast-forwarded tape. Unlike most dealings I've had with insurance carriers, my business with Criterion had been basically satisfactory. Yet there had been the seemingly inevitable slips in dealing with them, too: The phone people were always cheerful, helpful and sympathetic, but somehow, what got put into my envelopes didn't always match up with what I had understood was going to happen with coverage or costs.

Sure enough, when I peeled open the envelope, things were tangled. I’d called to drop coverage for the Ninja I'd sold and inquire about liability coverage for my Commando Production Racer, while maintaining coverage of my BMW. The woman on the phone understood it all, and read it back to me—twice—to ensure accuracy. Weeks later, the computer sent me a bill for insurance covering a Ninja and a Norton. But no BMW.

I decided not to let my stomach boil. Instead. I wrote two letters to the company: one to the underwriting department, the other to the president of the company.

Now, if you’ve had these kind of experiences and written those kinds of letters, you know what usually happens: nothing. But to my amazement, with Criterion, something happened. Fast. In response to my coverage letter, the vice president who called me assured me that he had personally seen to the fix, which involved installation of a new file-handling system. And in response to my letter to the president, he asked if I would like to meet with several key executives of the company to discuss motorcycle insurance in general and Criterion in particular.

This was too good an opportunity to miss. I had no doubt that the reason I was being thus treated was that I am a magazine writer. Still, here was a chance at last to bring home to some of the people who determine a significant piece of our riding experiences the view from our side.

The meeting was held on a bleak February day in Criterion’s Washington. D.C., headquarters. It was scheduled to take an hour. Two and a half hours later, it was still going strong. In those hours, three vice presidents—Gerald F. O'Neal, Daniel J. Coughlin III and Jesse L. Moore— and I moved from cautious exploration of why and how Criterion got into the bike-insurance business to brainstorming about how the company could improve its services and how the motorcyclists might minimize their risks.

If you think all this was somewhat less exhilarating than skimming a knee in Turn Eight with about 9500 rpm on the clock, you’re right, of course. But the receptivity of these men to what I had to say as a motorcyclist surprised and gladdened me.

When I suggested that they might improve safety in this country if they expanded the concept of their current reduction fora policyholder’s attending a Motorcycle Safety Foundation Rider’s Course, they asked for more. That led to a discussion of the needs of the high-performance rider, who nowadays sits on the most potent machinery on earth, but who has few non-racing opportunities safely to learn about its—and his or her own —limits. We talked about wqys insurance companies might influence legislation to aid rider training and ways they might reward “master riders.’’

Ideas flowed freely, and not all the notes taken were on my pad. As we talked frankly about the stereotypes, about why riders ride and speed and crash and hate insurance companies,

I was heartened that these guys were not trying to hand me the same old worn-out lines.

What was most heartening, though, was that these gents were talking to me because of good old competition. Our meeting was obviously part of their ongoing attempt to gain intelligence about their market— and, of course, to do a little PR—and that suited me just fine, because it gave me a chance to bring the enthusiast’s view into their decision loop, if only for a while.

Will any of this matter? Maybe. I have to believe that Criterion's willingness to explore new options is not an isolated phenomenon. Competition for your bucks makes me believe that. Criterion, by its vp's own admission, is still a bit-part player, with a tiny market share. Maybe that made them more willing than the leading people to listen. But maybe not. Maybe the long us-agin-them relationship between motorcyclists and insurance companies is ending, to be replaced with something more progressive and productive to reduce risks and rates. I hope so, anyway. I’d love to stop thinking of those envelopes as epistles from the enemy.

Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialCountering the Steering Myths

June 1985 By Pauldean -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1985 -

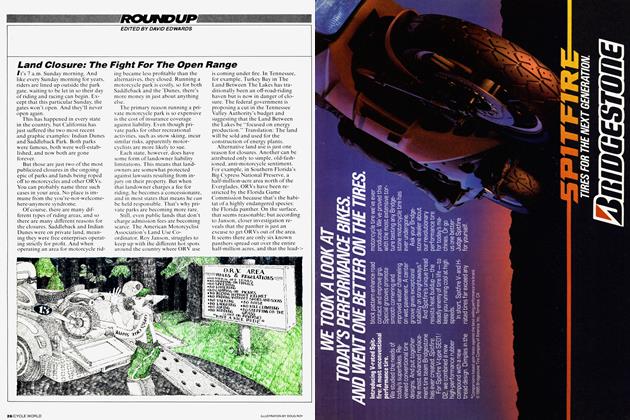

Rounup

RounupLand Closure: the Fight For the Open Range

June 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

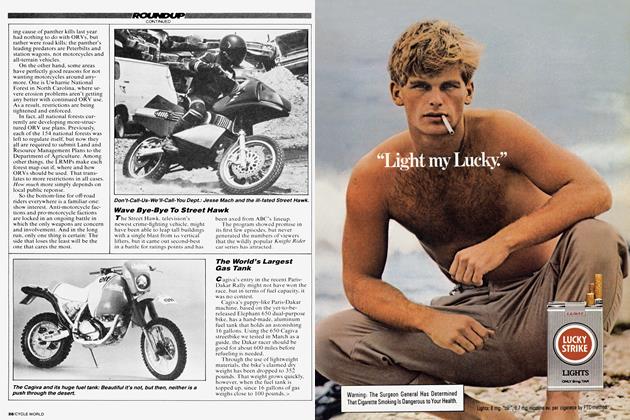

RoundupWave Bye-Bye To Street Hawk

June 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe World's Largest Gas Tank

June 1985 -

Roundup

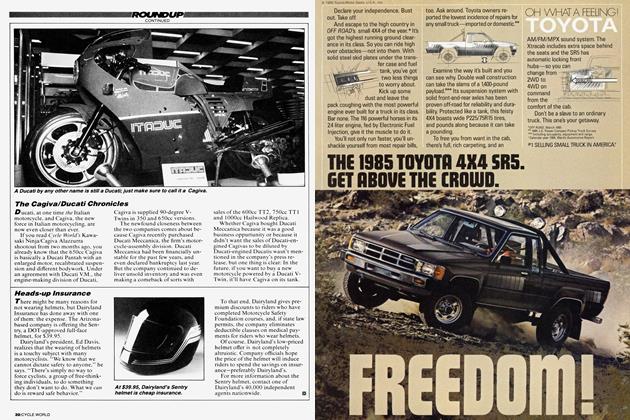

RoundupThe Cagiva/ducati Chronicles

June 1985