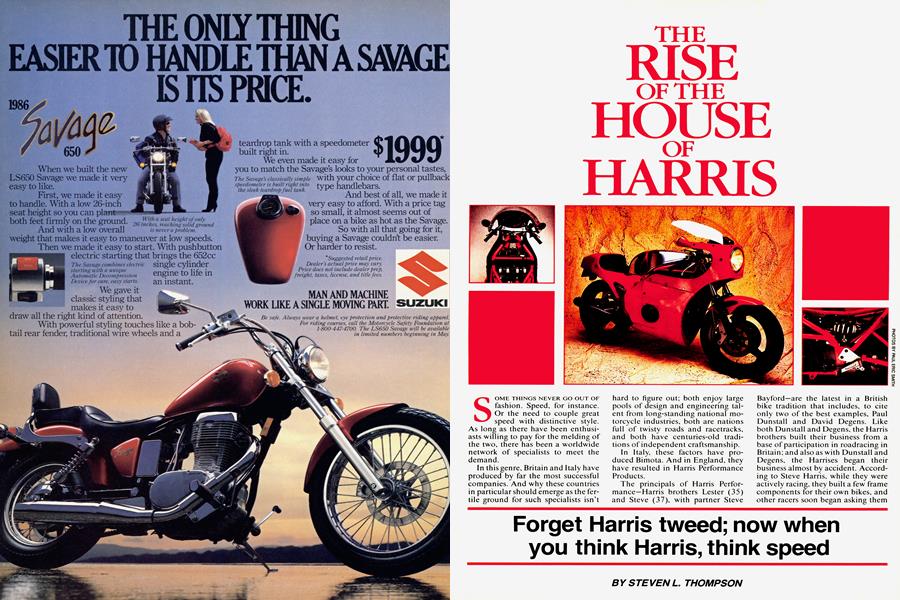

THE RISE OF THE HOUSE OF HARRIS

Forget Harris tweed; now when you think Harris, think speed

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

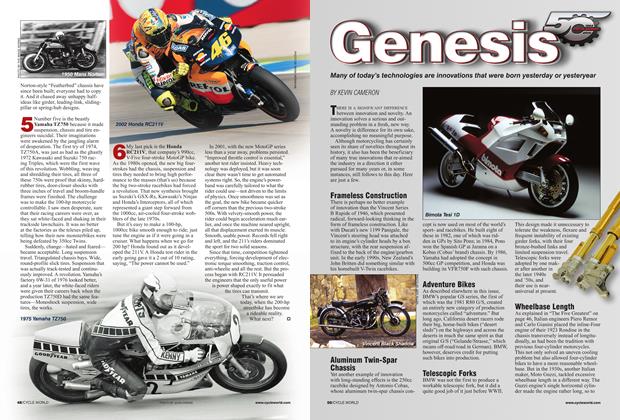

SOME THINGS NEVER GO OUT OF fashion. Speed, for instance. Or the need to couple great speed with distinctive style. As long as there have been enthusiasts willing to pay for the melding of the two, there has been a worldwide network of specialists to meet the demand.

In this genre, Britain and Italy have produced by far the most successful companies. And why these countries in particular should emerge as the fertile ground for such specialists isn’t

hard to figure out; both enjoy large pools of design and engineering talent from long-standing national motorcycle industries, both are nations full of twisty roads and racetracks, and both have centuries-old traditions of independent craftsmanship.

In Italy, these factors have produced Bimota. And in England, they have resulted in Harris Performance Products.

The principals of Harris Performance—Harris brothers Lester (35) and Steve (37), with partner Steve

Bayford—are the latest in a British bike tradition that includes, to cite only two of the best examples, Paul Dunstall and David Degens. Like both Dunstall and Degens, the Harris brothers built their business from a base of participation in roadracing in Britain; and also as with Dunstall and Degens, the Harrises began their business almost by accident. According to Steve Harris, while they were actively racing, they built a few frame components for their own bikes, and other racers soon began asking them

Getting Lester Harris to pinpoint the “secrets” of his success is easy: He answers in a single word—racing.

to build replicas. This went on for a few years until they finally decided to turn it all into a real business.

They began with a very modest two-room “works” in the back of a butcher shop in their tiny home village a few miles from Hertford, north of London. They complemented their building work by importing “bits” from Italy; and, presumably because they knew their stuff—their frames worked, in other words—they moved into an industrial estate in Hertford.

Today, Harris Performance occupies a three-story industrial plant, employs more than 35 workers to turn out about 300 frames a year, and builds everything for its bikes except the engines and electrics. That this adds up to a world-class success story is an understatement of almost British proportions. Especially in an era of depressed worldwide motorcycle sales, such success means that it's worth asking some questions about the Harrises; about what lies at the root of their fame and fortune, and about their philosophies and plans for the future—a future in which the Japanese factories themselves may continue to build machinery every bit as sophisticated and successful as the Harris supersports.

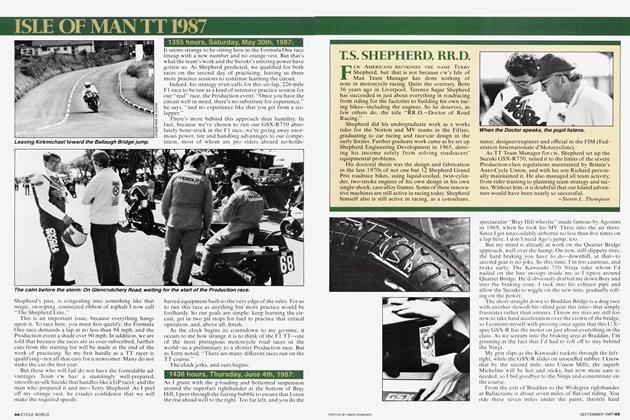

Getting Lester Harris to pinpoint the “secrets” of his success is easy; He answers with a single word—racing. In explaining his company’s rise to fortune, Harris stresses again and again that racing development is central to the success of his frames on the street. Through it, he tries new configurations, and from the racers who buy and use his frames he gets ideas for creating improvements. The result is continuous development, and a superb reputation among racers— which inevitably transfers to the street-only riders who always want the best from the track.

Harris’s words are not pure publicrelations hype. As you wander through the mazelike Harris works at

6 Marshgate Industrial Estate, you realize this commitment to racing permeates everything, every operation, every attitude, every worker. The people and machines that fabricate the Ducati TT2 frames for Steve Wynne also turn out street frames. Likewise, the exhaust-system man who welds up the Formula One pipes also puts together the plumbing for the Ford of Europe styling chief’s street-only Harris Magnum Three.

On the lowest level, in the cramped room where tube bending is the order of the day, where jigs stand everywhere, you come upon a Yamaha Genesis engine clamped in place, the embryonic beginnings of an exotic, welded-alloy “tub” frame around it, with a harried young man in a soiled shop coat intently using caliper, steel rule and eyeball to make it right, according to the master’s wishes. Racing photos, racing posters and racing relics litter the place.

Such attention to the track has paid off. Steve Harris estimates that the

company has built and sold more than 2000 frames worldwide, and riders on Harris machinery have done so well that the Harris Magnum Three brochure can confidently declare that, “With road racing success on 250cc to lOOOcc including 500cc Grand Prix we are the top privateer’s choice at every level.” Harris team rider Steve Parrish contests the TT Formula 1 British Championship and the World Championship, and Harris bikes have won the British F2 championship and pulled down second in the World F2 series.

To accommodate the shifting needs of racing, the wellsprings of the company’s life, the Harris works has inevitably become a kind of “bespoke” tailoring shop, where long production runs of anything are not possible. When I visited the works in September, 1985, and asked for a current catalog of Harris equipment, I was rewarded with a pair of wan smiles from both Harrises; things simply move too fast for such a catalog to stay current long, they explained, so there wasn’t one.

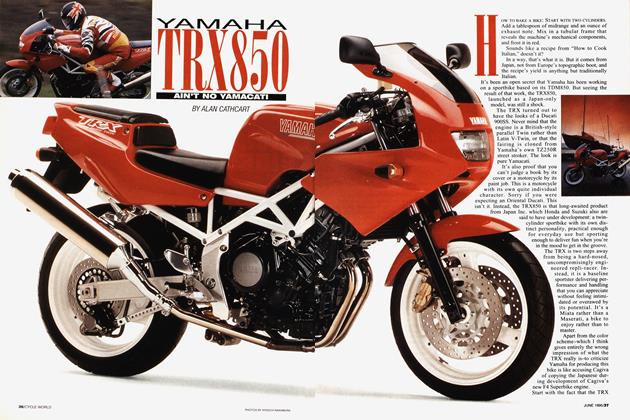

More poking into works rooms showed why. In addition to the Yamaha Genesis frame in progress; the final touches being put on the “new” streetbike frame—the newly christened Magnum Three, pictured here; further work on the TT2 frame; and other projects relegated to various corners of the factory, the brothers had recently been working on the then-secret Honda Single racer for Japan, as well as a government-sponsored, handicapped-person vehicle for local travel. What’s more, work was in progress with their preferred stylist, John Mockett (who worked on the Magnum Three), on a radical new supersport with the highest of high-technology chassis and body fittings. And, of course, there were the few special customer bikes being built, such as the one for the Ford/ Europe stylist.

At the end of the tour, despite be-

Getting on a Harris after riding a Ninja is like discovering there’s life after death: You knew it was possible, but until you experience it, you can’t believe it.

ing shown stacks of Magnum Two and Three fittings such as gas tanks, body panels, exhaust systems and frame components, it was obvious that “bespoke” really did define the operation; these guys will build whatever you want, as long as it makes sense and you’ll pay for it.

And pay for it you will; Harris stuff is not cheap, in any sense of the word. A frame kit alone for a Magnum Three listed at the end of ’85 for about $3000, while a rolling chassis (frame kit plus suspension, wheels and brakes) adds another two grand to that. So for about five thousand bucks (at $1.45 per British pound sterling) you have a bike almost ready to go—minus engine and electrics. You might think this steep price would prove a deterrent, especially since getting a good engine that fits the frame (at presstime, the M3 used only Suzuki GS1100, Kawasaki GPz750 Turbo and GPzllOO engines) can be a headache all in itself (see “Ask the Man Who Owns One— and Built Two,” pg. 61). Yet despite all this, Harris says his place is working virtually flat-out to meet demand.

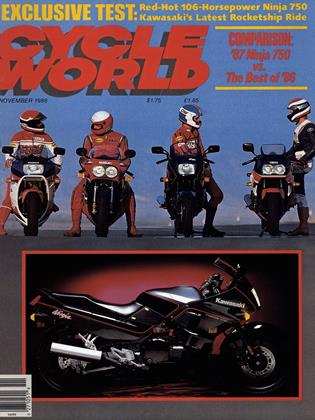

If you see in the older Magnum Two or the new Magnum Three simply a cafe racer of unknown lineage, you might be surprised at that. But all it takes is a fast ride on a well-assem-

bled Harris to see what all the commotion is about. Even in this era of literally awe-inspiring factory hardware, a fast run on a bike like Harlan Hadley’s Magum Two is enough to widen your eyes and make you wonder about your own bank account. Indeed, so compelling was his brief blast on Hadley’s mount that SaabScania of America’s president, Robert J. Sinclair, decided to have Hadley build an M3 for him.

Balanced performance, but without compromise, is the secret. When mated to good tires, even the older M2 chassis is so light, so responsive, so stable and even so relatively comfortable that chest-to-the-tank, pipeon-the-ground riding becomes not just possible but routine. Getting on a Harris after riding a Ninja is like discovering there’s life after death: You knew it was theoretically possible, but until you experience it, you can hardly believe it.

Yet not even the Harris brothers imagine that they can seriously dent the Japanese factory sportbike market. Indeed, Steve Harris says that when the first Ninjas and Interceptors exploded onto the market, he feared the worst. But precisely the opposite of a sales disaster ensued; the Japanese, he says, actually generated a huge increase in interest in his kind

of motorcycles, as the then-awesome bikes available from dealers quickly became all too common. Aware now of how good a stock bike can be, he says, many riders want more—more speed, more racer-like handling, more exotic looks. Harris Performance is happy to provide it.

About plans for the future, the brothers are guarded. Like all shrewd businessmen, they have concentrated only on servicing markets they understand. That has limited their serious sales activity to racers in Britain and the Continent, and to street riders in the same locales, although they have sent a few frames across the Atlantic. They are aware of the same forces working here in America that work in England—the continually escalating floor of what is considered true “high performance” among riders with a glint in their eyes and a wad in their wallets—but they are cautious about being overwhelmed by too much expansion too soon.

They have an American liaison for matters Harris (Bob Buchsbaum, 8000 Old York Road, Elkins Park, PA 19117; [215] 236-4571), but Buchsbaum is not a sales agent or distributor. Interested parties are encouraged to contact Buchsbaum first, but L1ester Harris acknowledges that ultimately, after a purchase has been decided upon, dealing directly with the works (6 Marshgate Industrial Estate, Hertford, Herts SGI3 7AG, England; telephone: 011-44-992551026) usually is required. He also acknowledges that if Harris Performance is serious about selling in the USA, eventually a different system will have to be established. But he’s in no hurry, apparently, and his company’s reputation among go-fast types as a shop that builds “poor man’s Bimotas” is keeping order books filled by enthusiasts for whom “stock” is never good enough, and for whom speed and style are commodities best melded in truly custom configurations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1986 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

November 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupBack To School

November 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

November 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

November 1986 By Alan Cathcart