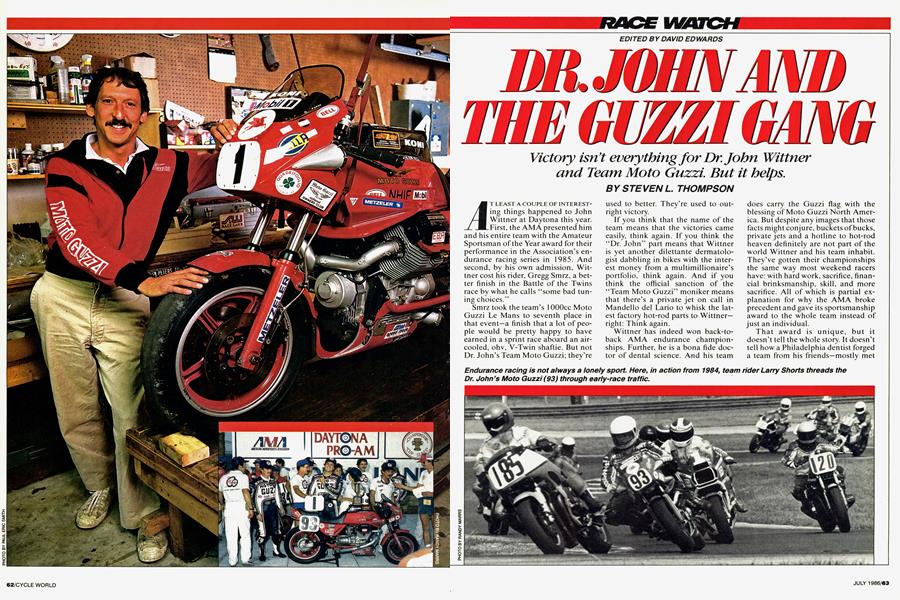

DR.JOHN AND THE GUZZI GANG

RACE WATCH

Victory isn't everything for Dr John Wittner and Team Moto Guzzi. But it helps.

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

DAVID EDWARDS

AT LEAST A COUPLE OF INTERESTing things happened to John Wittner at Daytona this year. First, the AMA presented him and his entire team with the Amateur Sportsman of the Year award for their performance in the Association's endurance racing series in 1985. And second, by his own admission, Wittner cost his rider, Gregg Smrz, a better finish in the Battle of the Twins race by what he calls "some bad tuning choices."

Smrz took the team's 1000cc Moto Guzzi Le Mans to seventh place in that event-a finish that a lot of people would be pretty happy to have earned in a sprint race aboard an air-cooled, ohv, V-Twin shaftie. But not Dr. John's Team Moto Guzzi; they're used to better. They’re used to outright victory.

If you think that the name of the team means that the victories came easily, think again. If you think the “Dr. John’’ part means that Wittner is yet another dilettante dermatologist dabbling in bikes with the interest money from a multimillionaire’s portfolio, think again. And if you think the official sanction of the “Team Moto Guzzi’’ moniker means that there’s a private jet on call in Mandello del Lario to whisk the latest factory hot-rod parts to Wittner— right: Think again.

Wittner has indeed won back-toback AMA endurance championships. Further, he is a bona fide doctor of dental science. And his team does carry the Guzzi flag with the blessing of Moto Guzzi North America. But despite any images that those facts might conjure, buckets of bucks, private jets and a hotline to hot-rod heaven definitely are not part of the world Wittner and his team inhabit. They’ve gotten their championships the same way most weekend racers have: with hard work, sacrifice, financial brinksmanship, skill, and more sacrifice. All of which is partial explanation for why the AMA broke precedent and gave its sportsmanship award to the whole team instead of just an individual.

That award is unique, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. It doesn’t tell how a Philadelphia dentist forged a team from his friends—mostly met in his dental chair as patients—and went racing with a machine most racers would sneer at, then simply laid waste to the competition, not just once, but race after race, for two full seasons.

To get to the bottom of that explanation, you have to begin with Wittner, the man who made it all happen—although in typical Wittner style, he will try to deflect credit for any of the team’s accomplishments to the other team members. But when you finally penetrate that genuinely self-effacing shell to winnow out the real John Wittner, you find, not unexpectedly, a motorcycle enthusiast of long standing.

Now 40 years old, Wittner has been riding since he was a teenager. An inclination to the mechanical led him to major in engineering at Lehigh University, but Vietnam intervened for him as for so many others of his generation, and he spent more time in Asia than at a drafting table. After Wittner changed out of Army green, his hankering for a medical profession outscored his desire for engineering and he plunged back into some hard schooling, receiving his DDS in 1975. There followed 10 years of what he calls total involvement with dental medicine, involvement that led him to a practice on Philadelphia’s posh Main Line and a chair on the Bryn Mawr Hospital advisory board.

As any motorcyclist knows, though, the riding habit is hard to break, and the special joys of racing even more so. Wittner says that the notion of going racing simply grew out of dental-chair conversations with some of his patients-men like Bob Griffiths (now the team's crew chief), Ed Davidson (team manager) and Noel Portelli (an early team rider). The way he tells it, one day the conversations got serious enough, and he had a racing team. Or almost.

First there was the problem of what to ride, and in which races. Early on, another friend of long standing, a local Harley-Davidson dealer, had liked the idea of Wittner doing flattrack racing with his shop’s sponsorship. But the deal fell through, and Wittner’s thoughts turned to the then-upcoming AMA endurance roadracing series. Although he had no personal endurance-racing experience, Wittner was attracted to long races, in which, other things being equal, the victory would go to the team not simply with the most horsepower, but with the best organization. The series promised to be more adult than sprint races. Since Portelli, at 27, was the youngest team member, the concept fit perfectly.

The choice of machine was not an easy one. Wittner—no millionaire— knew that the series would be expensive, a fact that made potential sponsorship a must. Like hopeful privateers the world over, he scrutinized each candidate motorcycle not just for its possible racetrack qualities but also for its possible draw of support. And like most of those privateers, he saw early on that expecting the American importers of Japanese bikes to provide serious sponsorship for an unknown team in a brand-new series was hopeless. Besides, the Japanese companies were ensconced in Southern California, a continent and three time zones away.

Moto Guzzi, however, was not. Guzzi’s national headquarters is in Baltimore, only 90 minutes from Wittner’s office in Philadelphia. Furthermore, Wittner, like many riders of his generation, harbors a special fondness for the Grand Prix giants of the 1950s, and Moto Guzzi was certainly that: Its 500cc V-Eight stunned the GP world when it appeared in 1955. Moreover, Wittner had, he says, always liked simplicity of design—and the Moto Guzzi 850cc Le Mans III was certainly a paragon of simplicity in an era of liquidcooled multis.

Having decided on the bike, Wittner says he simply walked in cold to the Guzzi headquarters in Baltimore and tried to acquaint the firm’s president, George A. Garbutt, with his vision of a Guzzi triumphant in the new series. Garbutt, a sensible veteran of the import wars, listened politely and said he’d get back to Wittner. Perhaps to Wittner’s surprise, he did. In January, 1984, the basic deal was struck, and Dr. John picked up his new Le Mans III.

You wouldn’t need to be a cynic to have bet a lot of money against Wittner and his V-Twin. Here was a completely untried combination of bike and riders in a wholly new series, giving away vast amoimts of horsepower to the competition, thrashing around on a motorcycle whose engine was derived from a 20-year-old Italian Army all-terrain vehicle designed for mountain warfare. But likewise, you don’t have to be Pollyanna to admit that sometimes, the power of positive thinking carries more weight than plain old power.

So it was with Wittner and company. They had positive thinking to spare, and the sense of sportsmanship that was to garner them a special AMA award two years later was already apparent: Unlike other teams, who often fenced off their pit and paddock areas in a pathetic attempt to emulate factory GP posturing, Dr. John’s team actually invited people in. As a result, they gathered big crowds of volunteers wherever they raced. In this, they were like the legions of Sunday racers who populate amateur racing in America. But for Dr. John’s Team Moto Guzzi, there was one big difference: They won. And kept winning.

At first, Wittner himself rode every race. And then, after their first Rockingham event, when they all realized they actually had a shot at the lightweight (GTO) title, he decided to concentrate on machine development and bow out of about half of the riding. In short, they got serious.

It worked. When the dust settled on the ’84 season, they had the points to win the title. Wittner credits Camel Pro rider Gregg Smrz as being one reason, along with the financial help they got from such unlikely sources as the Moto Guzzi National Owners’ Club, whose members responded with cash and checks to the team’s midseason plea for help. Moto Guzzi North America’s interest picked up, too, and although constrained by a severely tight budget, Garbutt did what he could to help the team make the races. And near Lago di Como, in northern Italy, the factory also took notice. Ties between Wittner and Moto Guzzi engineers were formed, and vital tuning information and parts “blanks” began to go westward from Mandello.

That unexpected success thrust some tough decisions on the team members. They had gone racing originally for the fun of it; as pure sport. But victory changed the psychic balance of payments. They all knew that the next year would be tougher than the first, when they had benefitted from the relative inexperience of all the competitors. Wittner says they all knew that they would have to be much better in ’85 to repeat ’84’s performance, and that the bike itself would be a limiting factor.

Emotional attachment is a luxury a competitor in a tough sport can ill afford—which is why most racers view their machinery as tools. If the tool is inadequate, it must be altered to adequacy; and if it cannot be made right, it must be disposed of.

Wittner and his crew were serious racers, and they knew that developing the vices out of the Guzzi—its infamous shaft-drive reaction, its moderate power delivery—might eat more of their time and money than the game would justify. Further, it might not pay off. Yet they had grown fond of the bike and were loath to abandon it. So in the winter of’84-’85, the decision was reached to persevere with a Guzzi, only this time it would be the new lOOOcc Le Mans IV.

In this decision lies one aspect of the team’s admirable “sportsmanship” officially recognized by the AMA. Many racers display courage, skill, determination and grace under pressure. Few have what might be called “heart”; and those few have the capacity to uplift everyone with whom they come in contact. This is not a quantifiable trait, nor is it unique to motorcycle racing. But in again choosing a Guzzi for 1985, Dr. John and his team showed that the sport in racing derives not from machines but from people; that when the center of a racing effort is based upon love of the sport rather than upon overweening ambition and sheer egotism, the sport itself becomes something much more than mere competition.

Particularly poignant proof of this

is evident from the dedication of Wittner’s team. The core crew consists of about 1 5 regulars and more than 35 auxiliary people who lend a hand (or a food hamper) whenever they can, not to mention the squads of Guzzi fans who troop hundreds of miles to stand near the Wittner pit, and often, he says, wind up working all through the race there.

In considering all this, it helps to realize that the core team is made up of people for whom racing on such an intense, continuous basis is no small commitment. Most of them are professionals—there’s a stockbroker and a hardware store owner among them—with families and lives apart from the endless laps of an endless series of endurance races. For them to stay with Wittner three seasons— unpaid in other than psychic terms— speaks of powerful bonds.

Those bonds were needed in ’85, as Wittner struggled to make the new Guzzi deliver the higher power needed to face the heavyweight competition. If the story of’84 was one of organizational work with a littlemodified motorcycle, the story of

their ’85 season was the opposite. Simply detailing what Wittner had to do to make the Guzzi competitive with the fearsome machinery of his rivals would fill a book; suffice to say that his work worked again, in concert with the skill of his riders and the organizational wizardry of managers Griffiths and Davidson. Naturally, there was a low point when it all seemed pointless, a moment in the season all racers will understand, when a small incident explodes out of proportion among a tired crew and the effort is threatened. The low point passed, and at season’s end, incredibly, they had another high point: overall victory.

For those who claimed that John Wittner’s ’84 championship was a fluke, for those who said that his team could never pull it off among the heavy-iron types, the championship was the perfect squelch. But after the celebrations came the nagging question: now what? Could they really expect to do it again in ’86?

Apparently, they think so. This year’s effort is fundamentally unchanged; the bike is basically the same, and so is the team (although Wittner says rider Portelli has emigrated to California and is out of the effort). Moto Guzzi N.A. now provides the basic operating funds for the races, and the lineup of sponsors has not changed much. Wittner has declared himself on indefinite sabbatical from his dental practice in order to devote full time to the season, a move of no small financial consequence, since he sold his home last year to help pay for the racing.

Wittner acknowledges that the team will face tough competition and even tougher decisions as this year’s racing goes on. He knows the old adage that “nobody wins forever,” as well as its unwritten corollary—first ruefully read by Harley-Davidson in 1969—“especially on an air-cooled, ohv V-Twin.” When asked whether the team would abandon Moto Guzzi if it should fall too far behind in speed, Wittner simply smiles and shakes his head, leaving the impression that the Guzzi is now too much a part of them all, too much the trusty steed for their quixotic adventure, to be put to pasture.

On the other hand, maybe to call their continuing quest for victory “quixotic” is mistaken, since Dr. John’s Team Moto Guzzi has what Don Quixote never had: clear-cut victories on the field of battle. They’re not tilting at racing windmills, they’re racing to win, and winning more than they lose. In that, they’re just like all champions everywhere. What makes them different is that in addition to being racers and champions, they are what the British call “true sportsmen.” Meaning that even when they lose, they win.

And, because of their example, so do we. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

July 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupSlowing the Insurance Liability Crisis

July 1986 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

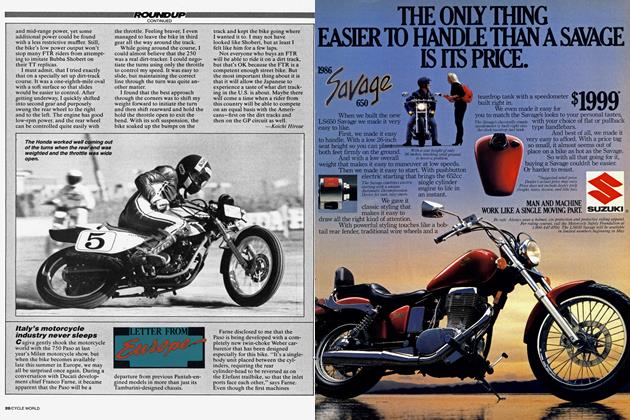

RoundupLetter From Japan

July 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

July 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

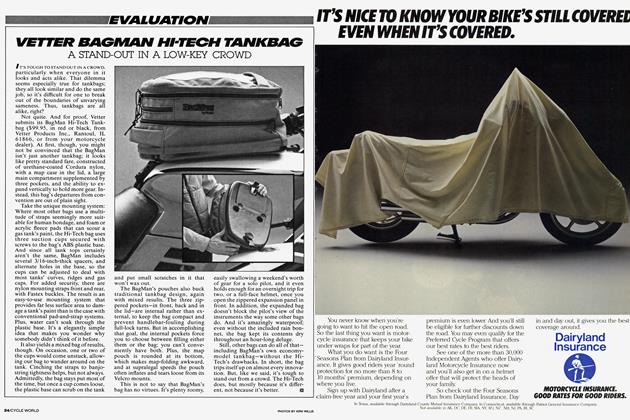

Evaluation

EvaluationVetter Flagman Hi-Tech Tankbag

July 1986