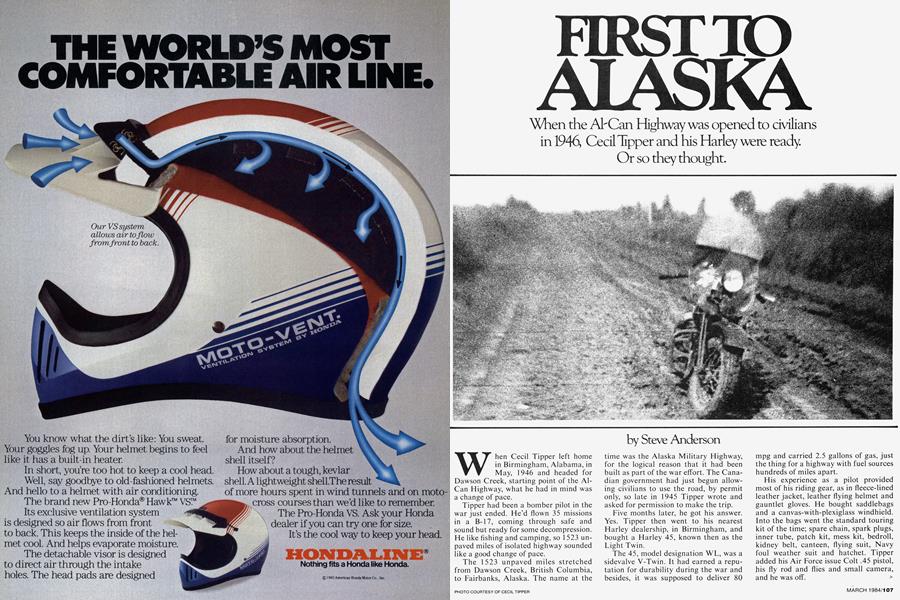

FIRST TO ALASKA

When the Al-Can Highway was opened to civilians in 1946, Cecil Tipper and his Harley were ready. Or so they thought.

Steve Anderson

When Cecil Tipper left home in Birmingham, Alabama, in May, 1946 and headed for Dawson Creek, starting point of the Al-Can Highway, what he had in mind was a change of pace.

Tipper had been a bomber pilot in the war just ended. He’d flown 35 missions in a B-17, coming through safe and sound but ready for some decompression. He like fishing and camping, so 1523 unpaved miles of isolated highway sounded like a good change of pace.

The 1523 unpaved miles stretched from Dawson Creek, British Columbia, to Fairbanks, Alaska. The name at the time was the Alaska Military Highway, for the logical reason that it had been built as part of the war effort. The Canadian government had just begun allowing civilians to use the road, by permit only, so late in 1945 Tipper wrote and asked for permission to make the trip.

Five months later, he got his answer. Yes. Tipper then went to his nearest Harley dealership, in Birmingham, and bought a Harley 45, known then as the Light Twin.

The 45, model designation WL, was a sidevalve V-Twin. It had earned a reputation for durability during the war and besides, it was supposed to deliver 80 mpg and carried 2.5 gallons of gas, just the thing for a highway with fuel sources hundreds of miles apart.

His experience as a pilot provided most of his riding gear, as in fleece-lined leather jacket, leather flying helmet and gauntlet gloves. He bought saddlebags and a canvas-with-plexiglass windhield. Into the bags went the standard touring kit of the time; spare chain, spark plugs, inner tube, patch kit, mess kit, bedroll, kidney belt, canteen, flying suit, Navy foul weather suit and hatchet. Tipper added his Air Force issue Colt .45 pistol, his fly rod and flies and small camera, and he was off.

The ride out of Birmingham was easy going, up through Memphis, St. Louis, Kansas City, Denver, over the Continental Divide and the Rocky Mountains to Grand Junction, Salt Lake City, Butte and then Sunburst, Montana before crossing over the U.S.-Canadian border at Sweetgrass, Montana and on to Edmonton.

A Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman greeted Cecil at the RCMP post in Edmonton and requested he lay out all his equipment for an inventory inspection.

The law would not allow the Army .45 automatic pistol. They kept it at the post for his return. And the RCMP insisted Cecil carry at least one day’s food ration, an indicator of what he might expect. And, before he could set wheel onto the highway he must have a letter from a motorcycle parts supplier who would agree to deliver any part he needed if he had a mechanical breakdown. Fortunately, a Harley-Davidson dealer in Edmonton was willing to provide that service for an advance, refundable fee of $100.

The RCMP was not all restrictive. They also provided him with some words of advice including warnings about the animals he might encounter including bears, wolves and moose. Basically the advice was to keep a good fire going at night and not get too close to a female bear with cubs.

At last clear of Edmonton, Cecil’s Light Twin ran smoothly in the cool Canadian air over the road that traversed the slightly rolling plains of Western Alberta.

May in Canada was chilly and required full dress behind the windshield. Canadian farmers on both sides of the road were working their spring chores on their fields in this section of the Peace River Valley.

Up to this point, Cecil had spent the nights in motels and hotels, but the Traffic Control Board guide provided by the RCMP showed not a single hotel or lodge from Fort St. John at mile 49 to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory at mile 917.

His first night out, just before Dawson Creek, was at Slave Lake where there was a good camping site next to the lake.

It was also his first hint of the abundance of wildlife. While setting up camp, he idly watched some Indian children fishing with a string at the water’s edge. Tipper could hardly believe it when the kids pulled a three-foot Muskelunge from the water. More surprising still, the giant fish, which would have been a record if not beyond belief back home in Alabama, was cut into pieces and thrown to the dogs.

Minutes later he learned for himself that fishing in such sparsely settled (and fished) territory didn’t require nearly as much skill or time as it did at home.

Dawson Creek was the official beginning of the military road, so Tipper checked in at a Mounted Police headquarters and found he was expected. This seemed a bit officious then but later, when he was waiting for the next vehicle per day, he came to appreciate knowing that somebody knew he was out there.

The fuel situation, though, still rankles after all these years.

First, gas was expensive, 85 cents per Imperial gallon. Next, presumably for reasons to do with the war or the military, gas was sold only in sealed 5-gal. tins. Nor could the container be re-sealed and taken along, so every time Tipper filled his tank he had to leave at least half his purchase behind.

Nor were supplies plentiful. The official guide for the 1523 miles, issued with the permit in 1946, consists of 17 places where there was anything resembling civilization. The legend has H for hotel, M for meals, G for gas and oil, R for repairs, C for checking station, A for airfield and S for stopover . . .whatever that means.

According to the official chart, Watson Lake (milepost 635) was a veritable metropolis, with S.M.G. and A. Whitehorse was ever more developed and boasted H.M.G.R.A. But the milepost there was numbered 917, meaning the distance between gas depots was 282 miles, impossible for the Harley. And he did run out of gas. He waited one full day for the next vehicle, a Canadian Army truck as it happened, and was treated to* a meal as well as gas.

Tipper had set himself a daily pace of 350 miles. The road was rougher and slower than anticipated. Most riding was done in second gear—the Harley had three—and mpg was reduced from the hoped-for 80 to 50 plus in the bad sections. Later Tipper figured he’d averaged 65 mpg.

West of Fort St. John, first official stop on the highway, the rolling farmlands of the Peace River gave way to forest as the road angled north and then west into the Rockies. There still was snow in the high passes. The early summer sun melted the snow, which eroded the graded dirt and sometimes froze overnight.

Once across the Rockies, the Highway bent and dipped, evidence of the Engineers’ interest in finishing the road fast. It wound its way around soft spots that might have caused delays, detoured around ravines that would have required bridging and headed over open country that required less clearing.

Surface conditions left a lot to be desired. Slight erosions, potholes, ripples, grooves left by trucks, and the loose gravel surface kept Cecil’s feet out or at the ready to steady the Light Twin. Progress was slow as he had to drive 35 mph most of the time.

Occasionally, when the road conditions eased, he was able to enjoy the scenery. On his third day out, he rounded one of the easy hills near the Rancheria River and 100 yards ahead he saw a large bear and two cubs. The Mountie’s warning came back. As he approached the bears, the female turned. He was still 50 yards away, Cecil recalled, and he hit the horn expecting to see them trundle off the road. No such luck. The female paused and pushed the cubs behind her. Cecil realized the risk so he opened the throttle and made as wide a sweep as he could on the narrow road. As he passed, the bear swiped at him with her paw . . . nearly causing an early end to the trip.

That night, at a trading post where Cecil was the only guest, the cookwaiter-clerk and charge d’affairs offered him a menu that included bear steak, moose steak, buffalo steak but no beef steak. Not a vengeful man, Cecil chose buffalo over bear.

Riding all day with not a single vehicle or person was strange. When the saddle of the Harley began feeling too close to his skin, Cecil stopped near a lake or stream and practiced fishing.

When he turned off the Harley, silence, absolute silence dropped around him. He would peel off his flying helmet and stand for awhile to let his body settle down from the ride.

At night, the awareness of being the only human for hundreds of miles was even more apparent. The stops were longer and there was not much of the night that was dark. Daylight hours increased steadily as he moved closer to the Artie Circle.

Every night he wiped mud and dirt off the chain, and added oil, checked the wheels for damage and tires for air pressure.

After building a fire from scrap wood, using his single weapon — the hand axe—and having something to eat, he would settle down and watch the wildlife watching him. Wolves, without being threatening, would occasionally sit in groups of three or four at a safe distance away and just look at Cecil looking back at them. None of the animals he saw were afraid of him. At mile 1221.4, a sign marks the border between Canada and what in 1946 was the Territory of Alaska. Koidern, at the south end of White Lake, was a trading post. Cecil stopped with just a little over 300 miles to go to Fairbanks.

When he drove into Fairbanks the following day, the city was not what he had expected. But word of his arrival had preceeded him and the Fairbanks Daily Miner interviewed him.

The windburned motorcyclist was news, the first man to ride to Alaska. He was quoted as saying, “the ride was a great deal rougher than I expected. Gravel on the highway really vibrated the motorcycle and darn near shook my teeth out. Tm glad I made it, but I’ve had enough. I’m going to sell my motorcycle and fly home.”

But after three weeks of walking the streets of Fairbanks, visiting the University and museum, and talking to people who stopped him on the street, he recovered from the trip. He also changed his mind about selling the Light Twin, so he repacked the Harley one June day and headed south.

While the trip to Fairbanks had been relatively trouble-free, the trip home was not. Two hundred miles outside of Fairbanks Cecil’s confidence on the gravel road turned to a moment of inattention which quickly resulted in the Harley turning in on itself. Cecil was thrown into the windshield and received a deep cut. The case guards saved the engine and Cecil’s legs from damage.

After three hours to stop the bleeding and clean himself up, he put the Harley’s contents back and re-established his confidence. Cecil thumped the Harley a few times and it started. He headed out again, very cautiously, and in a few hours reached a trading post. The proprietor cleaned and bandaged the wound. Cecil stayed there for three days, resting and recovering.

The rest of the trip was uneventful. Cecil did not have another problem until he reached Bismark, North Dakota. Mud and stones had ground the life out of the Harley’s rear sprocket and he had to replace it.

Eighteen days after leaving Fairbanks, he arrived in Birmingham. He had completed over 10,000 miles for a little over $500, not including the sprocket or the $419 he paid for the Light Twin. A year after the trip he sold the Harley for $425. Today he has retired from Westmoreland Coal Company as an electrician and lives in Crab Orchard, West Virginia.

But he has not retired from adventure. He is building a two-place airplane powered by a converted Volkswagen engine and expects to fly to his adventure spots in it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

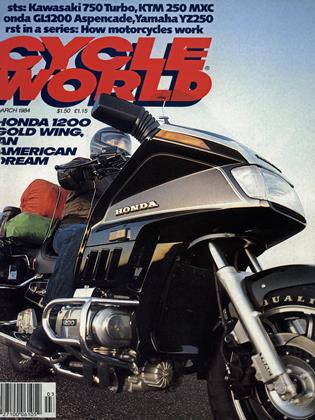

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

March 1984 -

Technical

TechnicalCycle World Follow Up

March 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

March 1984 -

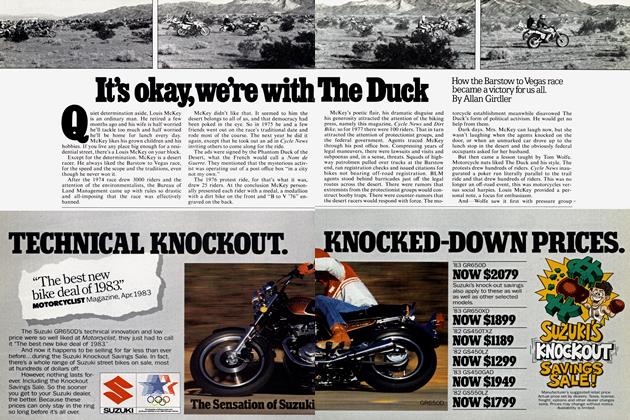

Competition

CompetitionIt's Okay, We're With the Duck

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

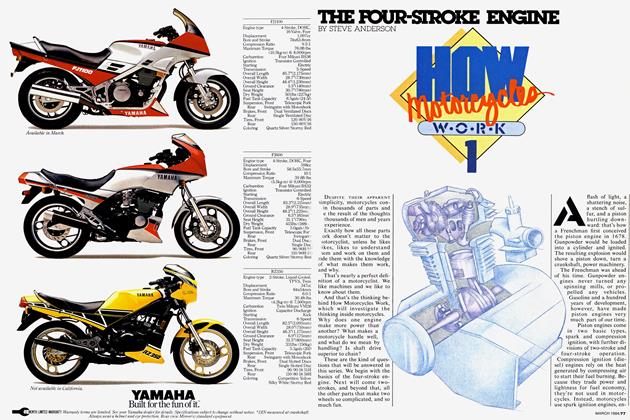

Special Feature

Special FeatureHow Motorcycle W.O.R.K 1

March 1984 By Steve Anderson