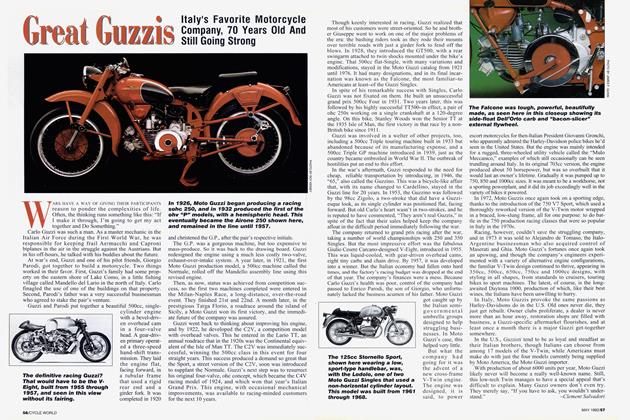

YAMAHA COMPARISON: YZ250 VS. YZ250 VS. YZ250

Ever wonder how a factory-modified YZ250 works bike stacks up against a stocker and a support-ride YZ? So did we.

Ron Griewe

For years, amateur racers have clawed their way up to the retaining fences at bigtime motocross events just to get a close look at the latest works machines. And for just as long, those same riders have fantasized about all of the races they’d be able to win if only they had one of those $50,000 factory bikes.

Until this year, however, the idea of racing anything even close to a factory motocross machine truly was a fantasy for all but a very few upcoming, highly talented riders. But that fantasy began to take on a bit of reality late last year when Yamaha announced that for 1984, its fully sponsored motocross riders would compete aboard modified production YZs. Hand-made works prototypes had simply gotten too expensive to build, and the decision had been made to use basically stock bikes.

Of course, that statement raised as many questions as it answered. First, exactly what did Yamaha consider a “modified production bike?” Were the Team Yamaha bikes actually close to stock or were they so extensively modified that they didn't resemble a production YZ in the least? And did the modifications to the Team bikes make them so hairy that only a top-level pro could ride them?

We decided to get answers for those kinds of questions in the only meaningful way: with an on-track comparison between one of Team Yamaha’s 1984 250cc factory bikes and a bone-stock YZ250. The factory-modified bike we borrowed was one of those ridden by Keith Bowen, Yamaha’s newest 250class star, and the stock YZ250 was the same one we had used in our March, 1984 test. The stocker had been thoroughly checked over and refurbished to insure that it was representative; and Bowen’s YZ also was representative, because, according to Yamaha, all the 250class factory bikes are virtually identical.

As an added attraction, we also borrowed an ’84 YZ250 that had been modified as outlined in Yamaha’s Wrench Report series. A Wrench Report, just in case you don’t already know, is a type of bulletin that Yamaha periodically sends to its dealers; each bulletin details various improvements and performance modifications that can be carried out by the dealer or the owner to make the production YZ or IT models more competitive. We included this “intermediate” YZ, as we called it, in our comparison simply because it is about as close to the factory bikes as the average rider will probably ever get. Matter of fact, many of the riders in Yamaha’s support program end up on bikes a lot like this one.

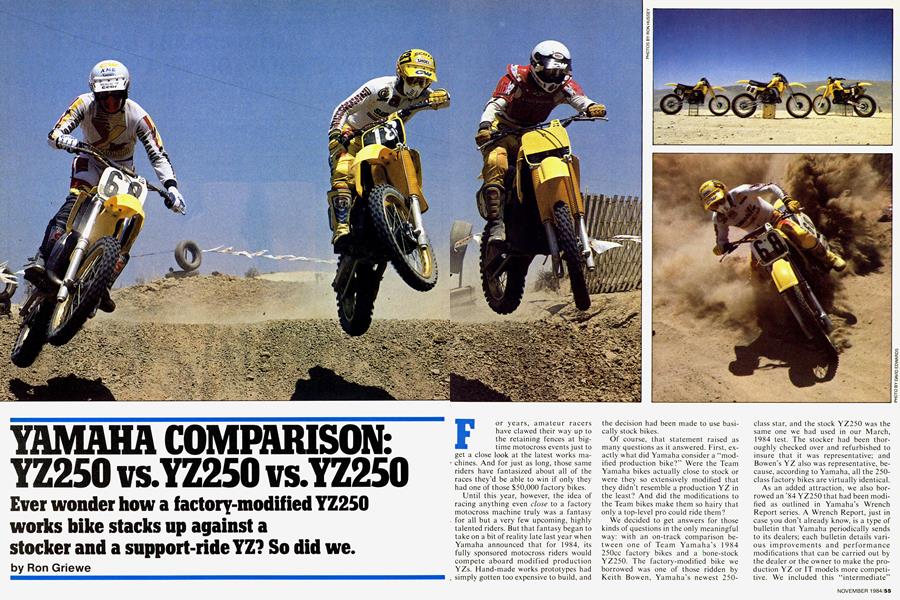

When the Cycle World crew (Test Editor Ron Griewe and Feature Editor David Edwards, plus Pro-class riders Rick Maki and Greg Zitterkopf) arrived at the racetrack, the three YZs were sitting on milk crates in the pits behind one of Yamaha’s race vans. But instead of us being overwhelmed by the sheer trickery of the factory bike, quite the opposite happened: It took a minute or two for us to determine which Yamaha was the works racer. Only the bike’s unpainted exhaust pipe and the aluminum spacer under its cylinder set it apart from the other two. Closer inspection revealed other changes to the works bike, but nothing as radical as we had expected.

Externally, the factory bike’s modifications include an Ohlins rear shock in place of the Yamaha-built unit; a flowtested, aluminum-bodied, steel-core Answer Products silencer instead of the stocker; strengthened radiator mounts; a shift lever that is 7mm longer than stock; and a clutch-actuating arm that is 10mm longer. In addition, the fork boots have been removed, and the standard wheel rims have been replaced with Takasago Excel rims that are claimed to be lighter and stronger. In short, the same kinds of things any owner could change.

Inside the engine, though, the modifications are more extensive. The 7mmthick aluminum plate under the cylinder is needed because the engine uses a 7mm longer connecting rod from a YZ490. The 490 rod has the same wristpin and crankpin diameters as the 250 rod, and it fits on the stock 250 crank; but it’s also heavier and needs to be lightened by machining grooves along the sides of the rod shank. The rod’s big-end radius has to be cut down to clear the 250’s engine cases, and the small end also is machined for further weight reduction. Still, the lightened rod ends up being almost 2 ounces heavier than the stock 250 rod.

What the longer rod does is change the rod-to-crankpin geometry. And that, in conjunction with the modified cylinder porting, not only results in more horsepower, but more power over a wider range of rpm. The chrome-bore cylinder, as well as the piston, the rings and the unpainted pipe used on the factory YZs, all are Yamaha-built GYT Kit (Genuine Yamaha Tuning Kit) items available to anyone through Yamaha’s Competition Support Department. And the porting used by the Team bikes is basically the same as detailed in Wrench Report No. 43. The 7mm cylinder spacer, however, is a custom part.

Having the cylinder and head sitting 7mm higher requires modification to the exhaust-pipe mounts and the cylinderhead stays, and to the linkage that actuates the exhaust power-valve. The pipe mounts and head stays can simply have their holes elongated with a file, but the power-valve linkage and its attendant cover have to be lengthened.

Otherwise, the factory YZ250s use stock clutches, gearboxes, shift linkages and bearings. For sandy or loamy courses the Team prefers the stock YZ250 internal-rotor ignition, with timing set somewhere between the standard 1.1mm BTDC and 1.5mm. The higher numbers produce a bit more power but a narrower powerband. For hard or slippery tracks, the Team mechanics generally install an external-rotor ignition from Yamaha’s YZ60 model—again, with ignition timing set somewhere between 1.1mm and 1.5mm BTDC, depending upon track condition and rider preference. The YZ60 ignition swap is a bolt-on, but does require that the YZ60 black box is used as well.

All the factory YZ250s use stock (but rejetted) 38mm Mikuni carbs, with AMPI Pro-Flow dual-foam air-filter elements in modified airboxes. The AMPI filters are of two-stage foam construction, much like the stock filters, but the layers are glued together to prevent separation. And the Pro-Flow elements are used only for one moto and then thrown away—not because they can’t be properly cleaned, but because that’s standard practice on factory race teams. They can’t afford to take chances with such inexpensive items. The airbox in each bike is modified for better airflow by the drilling of six 1.5-inch holes, three in the side, three in the top. The side holes have a thin layer of foam glued into them while the top holes are left uncovered.

There is, however, one area in which all the factory YZs are not alike: suspension setup. Each tuner modifies his bike’s springing and damping to suit track conditions or his rider’s particular style. Bowen, for example, prefers slightly stiffer front-fork rebound damping than most of the other Team 250 riders do, and he’s the only one who likes the damping provided by the off-the-shelf Ohlins rear shock.

If spotting the factory YZ250 was tough, finding the support-rider intermediate version was next to impossible. The internal top-end changes, obviously, can’t be seen, but a few others can—if you look real hard. There’s the extra mounting bracket on the radiator for strength; the added welds across the exhaust system’s headpipe and fat midsection where the tuning dimensions have been slightly altered; and the non-stock bolts threaded into the swingarm above and below the axle slot on both sides of the arm (see the drawing on pg. 57 ). The purpose of these bolts is to press against the aluminum chain-adjuster blocks inside of the swingarm and help hold them in place; some YZs have been known to let their rear axles shift, even when the axle nut is drawn up tight enough to distort the swingarm.

Modifying a stock YZ250 to these intermediate specifications can be done two ways. If you have a welder, the proper porting tools and the ability to use both, you can modify the bike fairly inexpensively by following Wrench Reports No. 43 and 48, which detail all of the changes to the ports, the pipe, the airbox, the swingarm and the radiator bracketry. Otherwise, you have to buy the GYT Kit, which includes a new pipe and a whole new chrome-bore cylinder, and you’ll still have to do the swingarm, radiator and airbox modifications on your own. Either way, we’ve reproduced both of the aforementioned Yamaha Wrench Reports on the following page just to save you the trouble of tracking them down on your own.

Once we got past the looking and started riding, finding the differences between these three bikes was much easier. We all had expected the long-rod factory bike to be an explosive, awesome handful. But it’s not. Instead, it makes smooth, predictable power, even though Yamaha claims it pumps out 8 more horses than a stocker. The added power is immediately noticeable, but its delivery is more like what you might get with, say, a 350cc or 400cc two-stroke Single rather than being like a hot-rodded 250 motor. The factory bike revs quickly and yet is very controllable. There’s never any sudden bursts of power, just a strong, constant rush.

Of course, this is the way the factory bike behaved with the YZ60 external-rotor ignition installed. And that setup proved ideal for the rock-hard, superslick adobe surface at Saddleback Park. Had we been on a track that offered more traction, the stock, internal-rotor ignition undoubtedly would have been a better choice. It’s our guess that in that configuration, the factory YZ will have a much more radical, abrupt powerband.

Nevertheless, the biggest performance improvement between the factory YZ and the stocker is not in the engine but in the rear suspension, because the Ohlins rear shock works like magic. Squareedged holes, abrupt chops, stadium-style whoops, landings from earth-orbit jumps—they all get soaked up almost as though they weren’t even there, with no rear-end kick or sidehop. The shock does all of this without feeling spongy or underdamped, and without any fade. The stock YZ250’s shock would fade noticeably after only four or five really fast laps on Saddleback’s cobby surface, but the Ohlins wouldn’t fade at all, even during a moto-long ride in the 95-degree temperature.

By comparison, the factory bike works better than the intermediate YZ250, but not necessarily just because of the rear suspension. The intermediate engine revs more quickly and is more responsive than either the stock YZ or the factory bike, but its power is harder to control. At low revs the engine pulls almost, but not quite, as well as a stocker, and in the midrange it’s about the same; but at the upper end of the midrange the engine suddenly comes to life and all hell breaks loose. Unless there’s excellent traction available, the rear tire spins violently and the bike tends to get sideways, especially coming out of the starting gate. As a result, most of our riders felt they could go faster with the stock engine.

Had we been riding on a sandy or loamy track or one that offered superb traction, the intermediate engine would have been a bonus. But on hard, slick tracks the stock engine is a better choice. For those conditions, the intermediate motor would be better off with the YZ60 external-rotor ignition instead of the stock YZ250 internal-rotor unit. We didn’t have a spare YZ60 ignition with us, though, so we couldn’t try it on the intermediate YZ.

That helps explain some of the results we got while doing various start-line drag races with the three bikes. The first session was on hard ground covered with a thin layer of sand—typical Southern California terrain. And there, the stock YZ250 won every single race—ten out of ten starts. The smooth, controllable power of the stocker made it easy to get off the line without as much wheelspin and tendency to get sideways. The factory bike and the intermediate YZ required a lot of throttle control and body English right at the very beginning of each start, and neither had enough of a power advantage to catch the hooked-up stocker before top speed was reached.

Next we moved to an area that offered much better traction, but the stock bike still dominated, winning 7 out of 10 drags. The intermediate bike won the other three, although all of the YZs were very close by the time they reached their top speeds.

We moved our drag-race location once again, this time to a hard-packed clay uphill. Surely, we thought, the power advantage of the works YZ would show up under these conditions. Wrong! After 10 more drags, the intermediate bike had won 5, the stocker 5. The works bike actually hooked up so well that the riders had to fight to keep the front wheel down when leaving the line. In the bike’s defense, though, it probably would have flat smoked the other two in this particular set of races—and maybe in one of the others, as well—had it been outfitted with a stock internal-rotor ignition that would have let it rev more freely.

Does that mean that Yamaha’s Wrench Report modifications, and its factory-modified works bikes, aren’t worthwhile efforts? No, not really. Both make noticeably more power than the stocker; and both undoubtedly would also be faster and more competitive than the stocker, given the time necessary to fine-tune their suspensions and play with ignition type and timing. Even at that, all of our riders loved the works bike, while most weren’t too fond of the intermediate YZ due to its inability to hook up easily or often.

More than anything, though, riding these three bikes side-by-side convinced us of one significant thing: The stock 1984 YZ250 has one hell of a good engine. So much so, in fact, that all four test riders came to the same conclusion: Considering the cost of duplicating the long-rod works bike, or even the Wrench Report intermediate model, the best choice for most riders and most tracks probably is a stock ’84 YZ250—with an Ohlins rear shock.

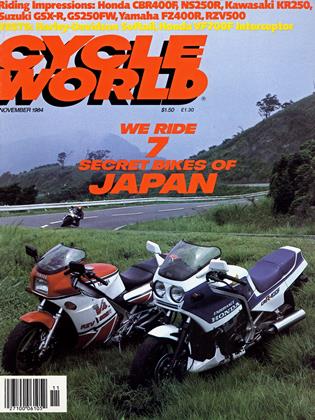

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cycle World Editorial

Cycle World EditorialOf Myths And Mystiques

November 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

November 1984 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupThe 15 Million Dollar Motorcycle

November 1984 By David Edwards -

Special Section

Special SectionBeyond Pit Road

November 1984 By Ken Vreeke -

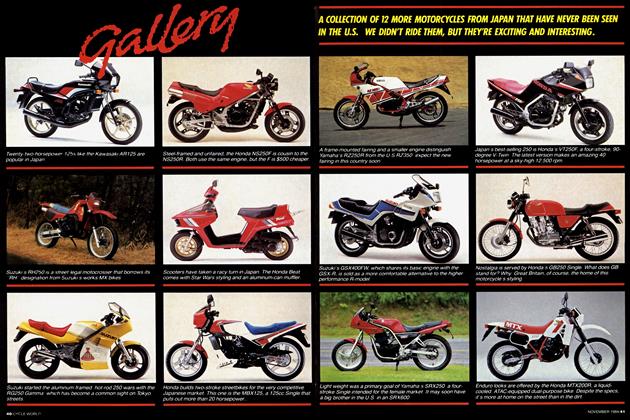

Special Section

Special SectionGallery

November 1984 -

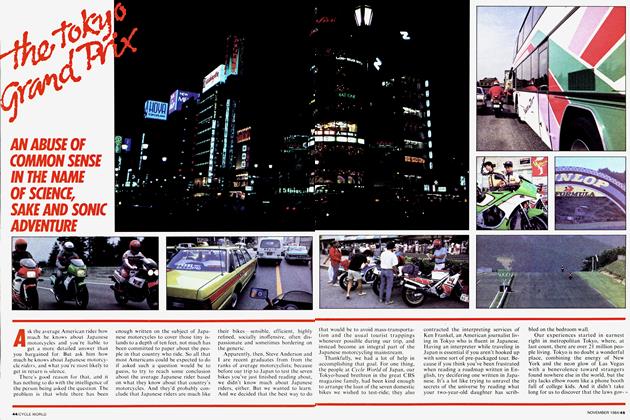

Special Section

Special SectionThe Tokyo Grand Prix

November 1984