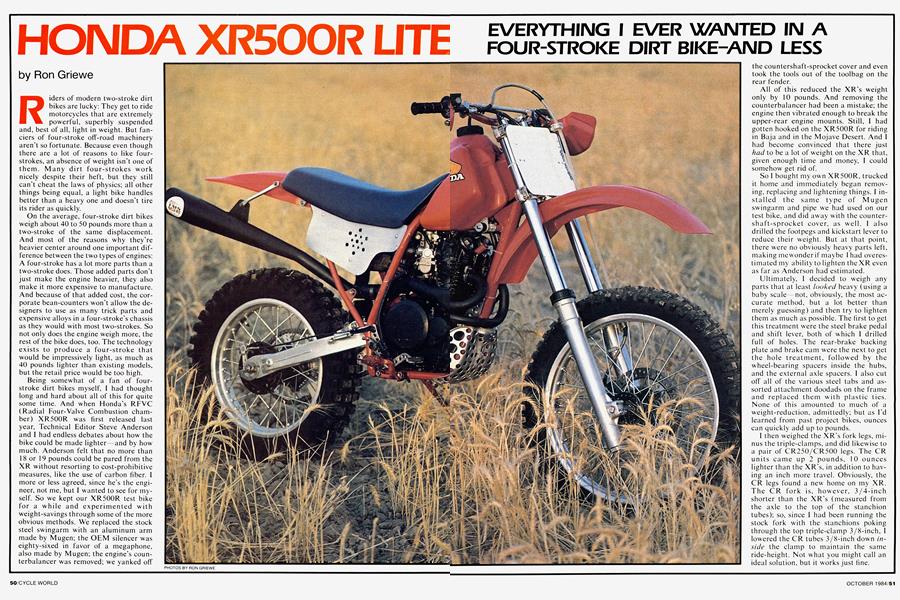

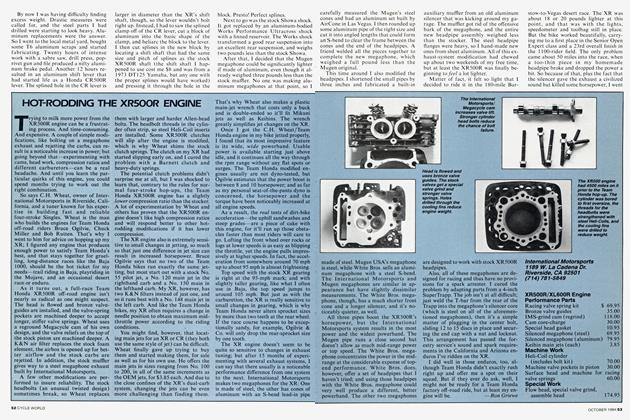

HONDA XR500R LITE

Ron Griewe

Riders of modern two-stroke dirt bikes are lucky: They get to ride motorcycles that are extremely powerful, superbly suspended and, best of all, light in weight. But fanciers of four-stroke off-road machinery aren’t so fortunate. Because even though there are a lot of reasons to like four-strokes, an absence of weight isn’t one of them. Many dirt four-strokes work nicely despite their heft, but they still can’t cheat the laws of physics; all other things being equal, a light bike handles better than a heavy one and doesn’t tire its rider as quickly.

On the average, four-stroke dirt bikes weigh about 40 to 50 pounds more than a two-stroke of the same displacement. And most of the reasons why they’re heavier center around one important difference between the two types of engines: A four-stroke has a lot more parts than a two-stroke does. Those added parts don’t just make the engine heavier, they also make it more expensive to manufacture. And because of that added cost, the corporate bean-counters won’t allow the designers to use as many trick parts and expensive alloys in a four-stroke’s chassis as they would with most two-strokes. So not only does the engine weigh more, the rest of the bike does, too. The technology exists to produce a four-stroke that would be impressively light, as much as 40 pounds lighter than existing models, but the retail price would be too high.

Being somewhat of a fan of fourstroke dirt bikes myself, I had thought long and hard about all of this for quite some time. And when Honda’s RFVC (Radial Four-Valve Combustion chamber) XR500R was first released last year, Technical Editor Steve Anderson and I had endless debates about how the bike could be made lighter and by how much. Anderson felt that no more than 1 8 or 19 pounds could be pared from the XR without resorting to cost-prohibitive measures, like the use of carbon fiber. I more or less agreed, since he's the engineer, not me, but I wanted to see for myself. So we kept our XR500R test bike for a while and experimented with weight-savings through some of the more obvious methods. We replaced the stock steel swingarm with an aluminum arm made by Mugen; the OEM silencer was eighty-sixed in favor of a megaphone, also made by Mugen; the engine’s counterbalancer was removed; we yanked off the countershaft-sprocket cover and even took the tools out of the toolbag on the rear fender.

EVERYTHING I EVER WANTED IN A FOUR-STROKE DIRT BIKE-AND LESS

All of this reduced the XR’s weight only by 10 pounds. And removing the counterbalancer had been a mistake; the engine then vibrated enough to break the upper-rear engine mounts. Still, I had gotten hooked on the XR500R for riding in Baja and in the Mojave Desert. And I had become convinced that there just had to be a lot of weight on the XR that, given enough time and money, I could somehow get rid of.

So 1 bought my own XR500R, trucked it home and immediately began removing, replacing and lightening things. I installed the same type of Mugen swingarm and pipe we had used on our test bike, and did away with the countershaft-sprocket cover, as well. I also drilled the footpegs and kickstart lever to reduce their weight. But at that point, there were no obviously heavy parts left, making mewonderif maybe 1 had overestimated my ability to lighten the XR even as far as Anderson had estimated.

Ultimately, I decided to weigh any parts that at least looked heavy (using a baby scale not, obviously, the most accurate method, but a lot better than merely guessing) and then try to lighten them as much as possible. The first to get this treatment were the steel brake pedal and shift lever, both of which 1 drilled full of holes. The rear-brake backing plate and brake cam were the next to get the hole treatment, followed by the wheel-bearing spacers inside the hubs, and the external axle spacers. I also cut olí all of the various steel tabs and assorted attachment doodads on the frame and replaced them with plastic ties. None of this amounted to much of a weight-reduction, admittedly; but as I'd learned from past project bikes, ounces can quickly add up to pounds.

I then weighed the XR’s fork legs, minus the triple-clamps, and did likewise to a pair of CR250/CR500 legs. The CR units came up 2 pounds, 10 ounces lighter than the XR’s, in addition to having an inch more travel. Obviously, the CR legs found a new' home on my XR. The CR fork is, however, 3/4-inch shorter than the XR’s (measured from the axle to the top of the stanchion tubes); so, since I had been running the stock fork with the stanchions poking through the top triple-clamp 3/8-inch, I lowered the CR tubes 3/8-inch down inside the clamp to maintain the same ride-height. Not w'hat you might call an ideal solution, but it works just line.

By now I was having difficulty finding excess weight. Drastic measures were called for, and the steel parts I had drilled were starting to look heavy. Aluminum replacements were the answer. So I went to the local metal yard, bought some T6 aluminum scraps and started fabricating. Twenty hours of intense work with a sabre saw, drill press, poprivet gun and file produced a nifty aluminum brake pedal. Another 12 hours resulted in an aluminum shift lever that had started life as a Honda CR500R lever. The splined hole in the CR lever is larger in diameter than the XR’s shift shaft, though, so the lever wouldn’t bolt right up. Instead, I had to saw the splined clamp off of the CR lever, cut a block of aluminum into the basic shape of the clamp, and heliarc the block to the lever. I then cut splines in the new block by locating a shift shaft that had the same size and pitch of splines as the stock XR500R shaft (the shift shaft I happened to use cost me $8 and was from a 1973 DTI25 Yamaha, but any one with the proper splines would have worked) and pressing it through the hole in the block. Presto! Perfect splines.

Next to go was the stock Showa shock. It got replaced by an aluminum-bodied Works Performance Ultracross shock with a finned reservoir. The Works shock transformed a good rear suspension into an excellent rear suspension, and weighs two pounds less than the stock Showa.

After that, I decided that the Mugen megaphone could be significantly lighter if made of aluminum, even though it already weighed three pounds less than the stock muffler. No one was making aluminum megaphones at that point, so I carefully measured the Mugen’s steel cones and had an aluminum set built by AirCone in Las Vegas. I then rounded up some aluminum pipe of the right size and cut it into angled lengths that could form an S-bend to clear the frame between the cones and the end of the headpipes. A friend welded all the pieces together to complete the new megaphone, which weighed a full pound less than the Mugen original.

This time around I also modified the headpipes. I shortened the small pipes by three inches and fabricated a built-in auxiliary muffler from an old aluminum silencer that was kicking around my garage. The muffler got rid of the offensive bark of the megaphone, and the entire new headpipe assembly weighed less than the stocker. The steel headpipe flanges were heavy, so I hand-made new ones from sheet aluminum. All of this exhaust-system modification had chewed up about two weekends of my free time, but at least the XR500R was finally beginning to feel a lot lighter.

Matter of fact, it felt so light that I decided to ride it in the 180-mile Barstow-to-Vegas desert race. The XR was about 18 or 20 pounds lighter at this point, and that was with the lights, speedometer and toolbag still in place. But the bike worked beautifully, carrying me to a first place in the Senior Open Expert class and a 23rd overall finish in the 1100-rider field. The only problem came about 50 miles into the race, when a too-thin piece in my homemade headpipe broke and dropped the power a bit. So because of that, plus the fact that the silencer gave the exhaust a civilized sound but killed some horsepower, I went back to the stock headpipe.

Racing the lightened XR500R in the B-to-V race convinced me that I should continue to try to cut weight off of the bike, regardless of the time and money required. So I swapped the XR500’s stock frame for a chrome-moly steel replacement from C&J Frames. I had the poeple at C&J build the new frame so it retained the stock XR geometry, as well as the original seat, gas tank and side numberplates. But I requested that they lower the backbone one inch where it meets the steering stem so the gas tank could sit lower, and that they move the oil filler plug atop the backbone ahead a half-inch just in case I ever needed to use a different gas tank.

While the C&J frame looked a lot stronger and less cluttered, it only weighed three pounds less than the stock unit. But, three pounds is three pounds. Besides, the C&J frame sells for $575, painted in the buyer’s choice of colorquite reasonable considering that the stocker goes for $525, is available only in red, and sometimes breaks in the area above the swingarm pivot.

About this time, Gil Vaillancourt, owner of Works Performance, dropped by to check out the XR. After walking around the bike a few times he commented, “It looks lighter, but you could drill the cylinder and head, you know. There’s nothing lighter than a hole!”

He was barely out of sight when I started removing the engine. Many, many hours later, after drilling the cylinder and head fins, as well as the decompression box (unused on the XR500R anyway), as full of holes as deemed safe, I took the parts to the baby scales. They weighed 2 pounds, 6 ounces less than before. While the engine had been out of the frame, I replaced the XR’s steel clutch plates with aluminum discs from a CR500R, knocking off another 8 ounces. I also had pared 4 ounces from the ignition by drilling holes into (but not all the way through) the external flywheel, directly out from the Woodruff key. And when the engine went back into the frame, I eliminated the manual and automatic compression-release cables. Like I said, ounces soon add up to pounds.

That attention to ounces, sometimes even to grams, led to the exchange of the stock handlebar for an aluminum bar made by Inter-Am. The Inter-Am bar is ounces lighter and has a bolted-on, solidaluminum crossbar, which is trick, but the crossbar attaches with cast-iron clamps, which are not. They had to go, so a machinist friend (what are friends for?) drilled holes in the crossbar and made new clamps of magnesium. The stock oil-feed hoses have steel fittings, so they were replaced with neoprene hoses from an auto supply store. Then I made a new chrome-moly sidestand to replace the stocker, and I gave the XR’s aluminum skidplate the hole treatment.

By now I was getting desperate. The speedometer, speedo cable and drive unit were removed (worth 1 pound, 6 ounces), and the headlight and taillight followed suit. Subtract another 1 pound, 1 1 ounces. The stock airbox is heavy, but several attempts to make an aluminum box had ended in lost time and added frustration. I finally decided simply to eliminate as much of the stock airbox as possible and use the remainder to shield a pair of K&N gauze-type elements. I cut away the top and both sides of the airbox, and removed the stock airboot and all of the hardware that holds the airbox in place. I used automotive-type pre-formed water hose with a 30-degree bend in the middle to connect the carbs to the 3-inch-by-4-inch oval K&Ns. A plastic plate pop-riveted to the front of the box (and cut out for the two hoses) protects the elements from whatever comes their way from that angle; plastic ties hold the modified box to the frame. Weight saved: 1 pound, 4 ounces.

I used aircraft aluminum, 0.032-inch thick, to form new side numberplates, which attach to the frame with quarterturn Dzus fasteners. When I cut out the sides of the airbox, I had been careful to trim them to the edges of the frame rails. Thus, the side numberplates, with the help of some weatherstripping glued to the insides of the plates, became airbox sides. A pattern of holes was drilled into the numberplates to help supplement the air that enters at the top of the airbox. For really wet going, the holes in the side plates can be taped shut.

My new airbox arrangement worked nicely but had a domino effect on several other parts of the bike. The side numberplates, for instance, made the bike so much narrower that the XR seat then seemed way too wide. So I bought a Kawasaki KX125 seat and adapted it to the XR. But first, the frame rails had to be reshaped and the rear subframe narrowed by 3/4-inch. Then the seat foam had to be reshaped using an electric knife and a rough wood file. A lot of work, yes, but at this stage, the one-pound weightloss was worth it.

Except that now, the stock gas tank and front fender looked much too big and bulky for the slimmed-down XR. So I fitted an XR250R tank, which is smaller, narrower and a full pound lighter than the XR500R tank. No, the 250 tank won’t fit right on, for it’s slightly longer (I congratulated myself for my foresight in having the oil filler plug moved ahead on the C&J frame) and hits on the 500’s valve-adjuster access caps. I heated the tank with a heat lamp to soften the plastic, then reshaped those contact points to gain the needed clearance. The front mounts won’t bolt up to the 500’s attachment points, so I made small aluminum brackets to adapt the tank to the frame.

For a front fender, I used a CR250R fender that required only some minor modifications. The two rear mounts had to be shimmed with one extra washer each for downtube clearance, and 3 inches of the rear of the fender had to be lopped off to clear the headpipe. While I was at it, I bolted up a CR450R rear fender, which also got the cut-and-fit treatment.

At this point, there weren’t many areas of my XR500 that I hadn’t either considered or already dealt with, but I did manage to think of one last thing: titanium! I know that titanium bolts are outrageously expensive and hard to find, but . . . many phone calls later, I found some titanium bolt kits, made for Maicos, at Wheelsmith Motorcycles. I bought two kits (individual bolts aren't available; just complete kits), one that contained 6mm bolts, the other 8mm and 10 mm bolts. After days of measuring, cutting and rethreading, I managed to replace almost all of the XR's case screws and most of the 6mm, 8mm and 10 mm bolts used elsewhere on the bike. And, after careful measurement, I also determined that the titanium axles that Wheelsmjth offers for Maicos could be modified to fit my XR. I swallowed hard and bought the expensive little suckers, knowing that the few ounces they saved were for a worthy cause.

Good thing, too, for I had to add a pound or two as the project developed. I traded the stock front tire for a 3.25-21 Metzeler, which is heavier than the stock tire but works so much better that I just had to use it. Both innertubes were replaced with heavy-duty red Cheng Shin tubes. And as a precaution against bruised knuckles during those rides through heavy brush, I installed a pair of the red plastic handguards that were stock on the ’84 XR500R. All in all, those few additions probably put 3 or 4 pounds back on my XR.

Not that I could tell once I was out on the trail, where the XR500R Lite, as I call it, is totally different from the stocker. Much of the weight reduction was up high on the bike, and its effects are immediately noticeable. The lightened XR isn’t top-heavy like the stocker; instead, it feels more like a two-stroke, with the majority of its weight fairly low. The slimmer, lower gas tank and the narrower seat make moving around on the XR an easier proposition. The rider can slide far enough forward to stop even the slightest hint of front-tire skate.

When charging through the whoops at high speeds, the XR now goes straight and usually hits the tops of the whoops rather than the middle or the bottom of them. The CR250 fork soaks up the bumps better than the stock fork did, and the extra inch of travel is a bonus at high speeds across the desert. And the Works Performance shock is nearly perfect; it doesn’t fade, and the rider never gets kidney-punched on those sharp bumps. There even is a noticeable improvement in traction, for the rear wheel follows the terrain instead of skipping when accelerating on rough ground. I also hopped-up the engine (see “Hot-Rodding The XR500R Engine,” pg. 52 ) to complement the XR’s weight-loss program. So the bike now accelerates much more quickly than the stocker and is more responsive to the opening of the throttle. It even stops better, which is one more bonus provided by the lighter weight.

Of course, accomplishing this hasn’t been easy. Building the XR500R Lite has taken up most of my spare time and much of my spare money. How much money? Well, I don’t know, and I don’t really care to add up all the bills and find out. The project was spread out over a period of 15 months, so the impact of the expense—in both time and cash—wasn’t all that terrible. I’d like to be able to tell you that the project is finally done, but I’d be lying if I did. White Bros, is working on a kit that will mount the White Power upside-down fork to a CR or XR, and that could knock another 3 pounds off of the XR Lite.

Getting rid of another 10 or 15 pounds, mostly in the engine, would undoubtedly cure the XR’s worst remaining problem, which is its awkwardness in tight sandwashes. But an XR owner can’t reasonably hope to accomplish such a feat. That’s a job for Honda, and XR riders—me included—can only hope that the next generation of XR500R four-stroke engines is lighter. Until that happens—if it happens—I seem destined to spend most nights out in my garage, trying to make the XR even lighter yet. S

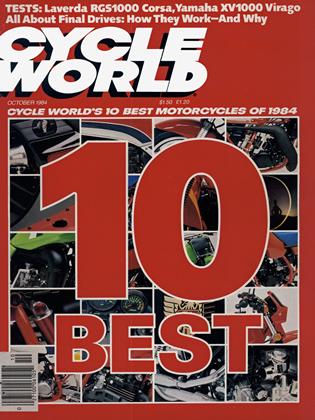

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Editorial

October 1984 By Paul Dean -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

October 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

October 1984 By David Edwards -

Features

FeaturesHot-Rodding the Xr500r Engine

October 1984 By Ron Griewe -

Technical

TechnicalHow Motorcycles W·o·r·k 5

October 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Things To Do

October 1984