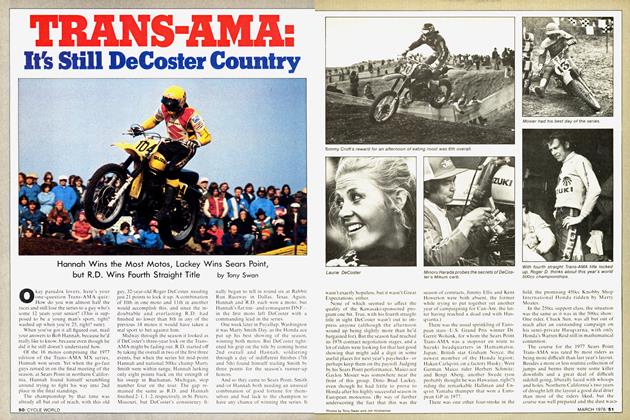

BATTLING BAJA

The Baja 1000 Score Is Now Race 3, Griewe 0

Ron Griewe

You’ve heard the wisdom about how to finish first, first you must finish? How come nobody ever talks

about how to finish? That’s the hard part.

This was my third try at the Baja and this time, I thought, I was ready. My Yamaha TT500 has a Profab frame and swing arm, the engine is bored to 540cc, has a Webcam #88 camshaft, head work, Dellorto carb, 38mm leading-axle Betor forks, Works Performance gas-charged shocks, and two super bright halogen headlights rigged by our own electronics wiz. Never mind that last year the bike broke and the year before that, I don’t like to talk about. This time, for sure.

Bike riders are required to be at the Naval Base impound area at 5:30 a.m. We picked our bikes up in the dark, for escort

x' T

to the starting line across town.

My bike fired third kick . . . and kept on firing. Back-firing, with flames shooting three feet behind the megaphone. The head pipe then proceeded to turn cherry red and glow in the pre-dawn darkness. A heavy sinking feeling engulfed me. My two previous DNFs took place during the race. Now, it looked like I wasn’t going to get to the starting line.

About the time I thought all was lost, it smoothed out and the red started fading from the head pipe. Hope returned.

Some 81 bikes made their way through the downtown section and back streets of Ensenada en route to the starting pad at the Country Club. Only 31 of these would cross the finish line. Rain had been scarce this year and the outlying dirt streets were very dusty in the half light of dawn. Three hundred feet from the starting area chaos broke out. Bikes were dodging around in all directions. The cause was a sewer ditch running right down the middle of the street! In typical Baja form it wasn’t marked with barricades, lights or anything. The first few riders managed to dodge it but the dust and darkness made it hard for those farther back in the pack to see and several people rode right into it. One poor guy hit the beginning of it and followed it in until his bike came to rest with the bars on the street and the rest of the bike in the ditch. Others rode into it at an angle and got swallowed. Luckily most missed it. One racer on a Yamaha was greeted at the start area with a flat front tire. With help he repaired it before his starting time.

Natural and man-made hazards are all part of Baja racing. An area that was fast and smooth yesterday may have a couple ditches across it by tomorrow—without any warning devices, naturally.

The Baja races are looked forward to by the kids along the race route. It’s an exciting time in their lives and a lost part or piece of riding gear (goggles, etc.) becomes a cherished possession. They also like to see the riders crash. The first 80 miles of the course were littered with dirt mounds (12 in. wide by 12 in. high), all the way across the road. In the Sierra Juarez mountains some of these booby traps were even camouflaged with pine cones and sticks. The kids got great joy out of seeing the crazy gringos bound over these obstacles. Most were harmless but a few were very dangerous.

The second cattle crossing leaving the town of Ojos Negros is a good example. It’s on an 80-mph-plus straight and is usually rough enough without being boobytrapped. Someone piled just enough small branches in front of it to add to the hazard. An unlucky 125 racer, partially blinded by the rising sun and heavy dust, endoed hard at this spot but luckily wasn’t injured.

Farther down the course just before Check Two a giant rock was carefully hidden by a green bush. This rock had been moved into the path on a rough downhill. I didn’t talk to anyone who was unfortunate enough to hit it, though. By this time the racers had pretty much caught on—if you see a group of locals watching and waving you on, slow down, a booby-trap is ahead!

The Baja 1000K is always tough and this year was no different. The course had been changed some from last year. This year’s course followed the 500 course exactly but the section from Nuevo Junction to San Felipe and back over the dreaded summit was run twice. This made the race 660 miles long and many early leaders never got to the checkered flag.

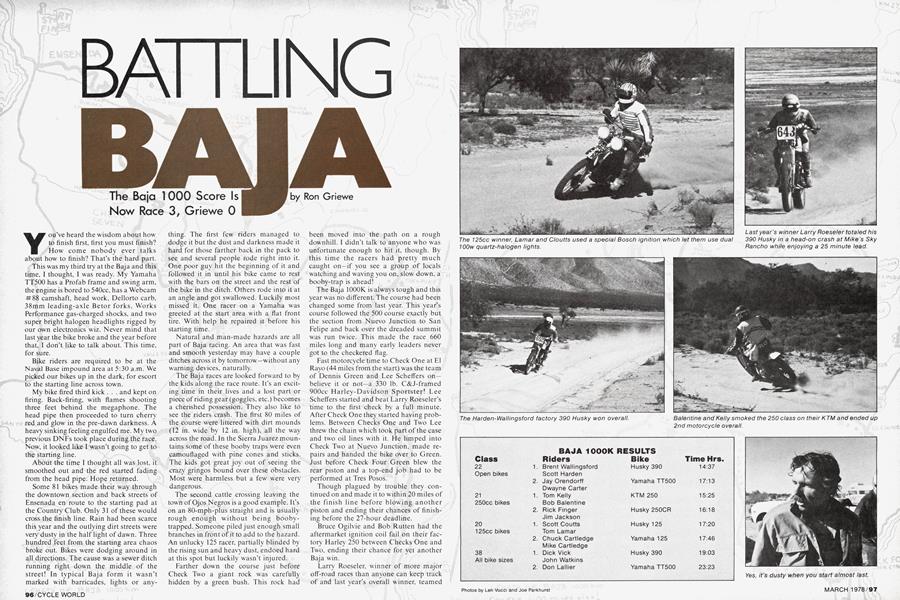

Fast motorcycle time to Check One at El Rayo (44 miles from the start) was the team of Dennis Green and Lee Scheffers on— believe it or not—a 330 lb. C&J-framed 900cc Harley-Davidson Sportster! Lee Scheffers started and beat Larry Roeseler’s time to the first check by a full minute. After Check One they started having problems. Between Checks One and Two Lee threw the chain which took part of the case and two oil lines with it. He limped into Check Two at Nuevo Junction, made repairs and handed the bike over to Green. Just before Check Four Green blew the rear piston and a top-end job had to be performed at Tres Posos.

Though plagued by trouble they continued on and made it to within 20 miles of the finish line before blowing another piston and ending their chances of finishing before the 27-hour deadline.

Bruce Ogilvie and Bob Rutten had the aftermarket ignition coil fail on their factory Harley 250 between Checks One and Two, ending their chance for yet another Baja win.

Larry Roeseler, winner of more major off-road races than anyone can keep track of and last year’s overall winner, teamed with Jack Johnson for another try.

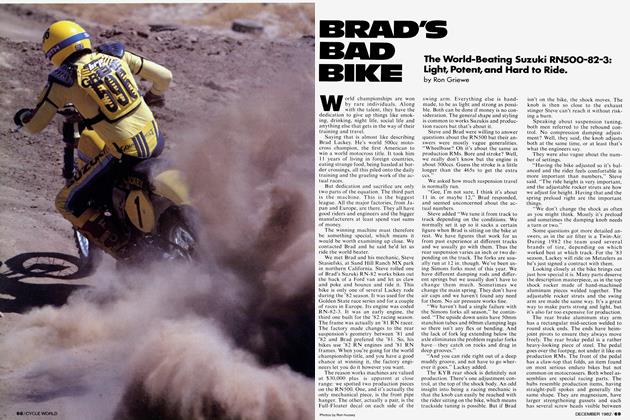

BAJA 1000K RESULTS Class Riders Bike Time Hrs. 22 1. Brent Wallingsford Husky 390 14:37 Open bikes Scott Harden 2. Jay Orendorff Yamaha TT500 17:13 Dwayne Carter 21 1. Tom Kelly KTM 250 15:25 250cc bikes Bob Balentine 2. Rick Finger Husky 250CR 16:18 Jim Jackson 20 1. Scott Coutts Husky 125 17:20 125cc bikes Tom Lamar 2. Chuck Cartledge Yamaha 125 17:46 Mike Cartledge 38 1. Dick Vick Husky 390 19:03 All bike sizes John Watkins 2. Don Lallier Yamaha TT500 23:23

Larry and Jack had a 25-minute lead when Roeseler stuffed their factory Husqvarna 390 OR head-on into a VW bus near Check Six at Mike’s Sky Rancho. Larry tweaked an ankle and was bruised but fared better than the bike. It was nearly totaled.

Don L’Allier spent three hours stuck in the mud (at night) on a small and normally dry lake by El Rodeo; got lost around El Alamo but finished about 5:45 a.m. Saturday. As he rode up to the finish line he was met by Number 756, the Fox-Hale PE Suzuki, going the wrong way! The rider had ridden up to the finish line, stopped and looked around, then turned to ride away. Luckily someone stopped him, but the disorientation caused them to finish 3rd instead of 2nd in Class 38 by only one minute.

This type of action is typical of Baja 1000s. After hour upon hour on a motorcycle staring at a quartz light beam in the blackness of the Baja night, one begins to hallucinate. People seem to jump from the bushes and call to you, gray horses look like ghosts, reaction time becomes so slow that hazards are past before the brain is aware they exist.

Back in my own race, partner Pete Wilkins and I had high hopes of winning Class 38.1 started and began passing other riders within a couple miles. After having traveled this first section more than a dozen times the last couple of years, the heavy dust and rising sun was less of a handicap for me. Several riders were behind me by Ojos Negros, and on the fast rolling straight leaving town I reeled in two more. The rough second cattle crossing gate came into sight. We’re supposed to have a gas pit here some place. Panic. There were at least 100 spectators around the cattle crossing. I didn’t see the CYCLE WORLD banner that signaled a pit and at speed spectators become a blur of color. I hit the crossing at more than 60 mph with the throttle off. Definitely not the way to enter a rough jump, but in my search for the gas pit too much concentration had been lost. The bike jumped into the air sideways and landed on the other side with one wheel in each sandy rut. A short wrestling match followed and a crash was barely avoided. I could find no banner, or pit, or familiar face. Now what? My thirsty Yamaha with its 540cc won’t make it to our first rider change (87 miles). Maybe I’ll see someone I recognize and beg gas from them. Yes, that’s the thing to do. Three miles down the road the Spoke Benders’ red sash drew me in like a magnet. (My club and the Benders have communal pits at many desert races.) I didn’t readily recognize the pit crew but asked if I could bum a gallon of gas anyway. “Sure,” was the answer and one guy took off in a run to get a can of gas from his pit truck. The can spout proved harder to find and a couple long minutes went by. Two people raced past and I got a little uneasy. But I knew it was better than running out in a remote place and having everyone pass.

The nice people were pouring gas in by now and the tank level was lower than I had guessed. I thanked them and hurriedly tried to start the big thumper. One, two, three, four, five, six kicks later it was running and I tried to leave without throwing sand all over my saviors.

The big Yamaha’s scary top speed helped me reel in another four or five people before El Rio and Checkpoint One. Sure felt good to have lots of power climbing into the mountains. I had a couple bikes pass me in this section last year when I was on a 250.1 decided to come back with a big engine this time—touché!

The neat sand roads through the pines soon were behind me and the course dropped into the high desert. A few miles later Check Two came into sight. After sliding in and dismounting, the bike was gassed and Pete crawled on, kicked the bike over and was gone in a cloud of dust.

Our pit crew said we were one minute behind the first Class 38 bike into Check Two but actually one minute ahead of them on corrected time. We had started almost last in our class, so we figured we must be in the lead (the time board later showed the team of Dick Vick and John Watkins, who started last, tied with us on corrected time at Nuevo Junction).

We left Check Two in my van and headed out to the pavement and southeast to El Chinero, our next rider change. Twenty minutes before Wilkins was due, Jim Hansen, our chief pit man, started urging me to get dressed. “He’ll be here any minute, get your gear on,” he commanded.

Ten minutes later the Vick/Watkins Husky screamed by. Then the Axthelm/ Smith Kawasaki followed by Don L’Allier on a stock-framed TT500. @*&$. Where is Wilkins? Hope he hasn’t crashed. Maybe his hand is bothering him. His left one was swollen badly this morning from a spider > bite. Maybe he had a flat tire. Damn!

Finally he roared in. “Had a flat tire 10 miles after I got on, the rear one,” he offered. “Good thing we had spare wheels with Jim Crow at Check Three. Took a while to change it though, couldn’t find a big enough wrench for the axle nut.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I assured him. “We have a lot of miles left to catch up.” His time had actually been good considering he had to ride 30 miles of downhill sandwash with the flat rear tire and had problems changing it. Hansen was yelling at me again, “The bike is ready, get on and get out of here!”

I left and almost immediately the engine started pinging badly on the bottom end. “I’ll just try to ride around the ping, keep the rpm higher and avoid turning the throttle all the way off, sure, that will do it,” I tried to convince myself. Twenty miles later the ping was worse and I stopped at the first pit that came into sight. They cheerfully loaned me a screwdriver and I richened the pilot system as much as the external adjustment allowed. No difference. The pinging continued. I continued . . . and hoped.

The course had turned and headed away from the gulf now and the sandy doublerut road was leading to Laguna Diablo, a 16-mile long normally dry lake bed. With the lake bed in sight, the engine suddenly seized. I pulled in the clutch and coasted from 80 mph to a dead stop. Four-strokes aren’t suppose to seize. What’s wrong? I found neutral and nudged the kickstarter— it turned over fine. A healthy kick followed and the motor came to life, sounding good! Maybe a rock got between the chain and sprocket and stopped the motor. Or . . . the lake bed has been reached by now and the engine which I know is capable of pushing the bike in excess of 100 mph is having trouble getting to 80. I tucked in road-racer style and the motor instantly responded by seizing again. This time the bike decided to get sideways before I could move my left hand from the fork tube to the clutch. Before it stopped rolling I dropped the clutch and it started again. I put the handlebar choke lever full on and tried to baby it a little farther.

The upper end of the lake was still wet and the engine had seized two more times by now. There’s Tim Smith on the Kawasaki. He was having seizure problems too. That moves us up to 3rd in class but the motor doesn’t sound like we are going to stay here long. A couple of miles of twisty sand road and the course turns into a wide straight five-mile long upgrade that would be safe at 200 mph if anything could go that fast on it.

Less than a quarter mile up this fast road the engine started sounding like a coffee can half full of marbles. The terminal seizure struck, and I became a spectator— again. (A later teardown showed the pinging had caused some of the ring lands on the big bore Protec piston to break off and the rings had broken into short pieces. This let the compression blow into the bottom end and forced the oil out the breather tube. Without oil the piston seized.) Anyway, a few racers passed and then a Datsun pickup stopped. The Mexican driver spoke English fairly well and offered me a ride. I accepted and we loaded the bike. Of course, he didn’t have any way to tie it in so I stayed in back to hold it upright. The driver was on the race course and decided to play racer. With me in back trying to hold the bike. I was glad my helmet was still on. I gave up trying to hold the bike and laid it on its side, then sat on it to try to hold it in the bed. When the Datsun’s engine sputtered and died I was almost relieved. The men jumped out and threw up the hood. One came back and asked if I had a fuel filter in my tool bag (theirs was plugged solid). I didn’t, but we took the one off the broken race bike and installed it in the gas line on the pickup. We were on our way again.

Three miles up the course they dropped me off at my pit and left (they wouldn’t accept any money so I tried to give them a pair of MXL goggles. “No thank you” was the reply. “We helped you and you helped us,” the driver smiled.)

I have heard many horror stories about Baja but so far all of my own experiences have been more like this. Baja beat me again. The score: Baja 3, Griewe 0.

Such is Baja racing. Men and equipment pushed to their limits and sometimes beyond. Everyone knows that if they win it will mean the race has only cost them a couple hundred dollars each. But the spirit of competition and the memories of going 100 mph across a 16-mile lake bed at 3 a.m., a quartz-halogen light cutting a small pathway through the dust and fog, can’t be equaled at any price. 03

View Full Issue

View Full Issue