KAWASAKI KDX200

CYCLE WORLD TEST:

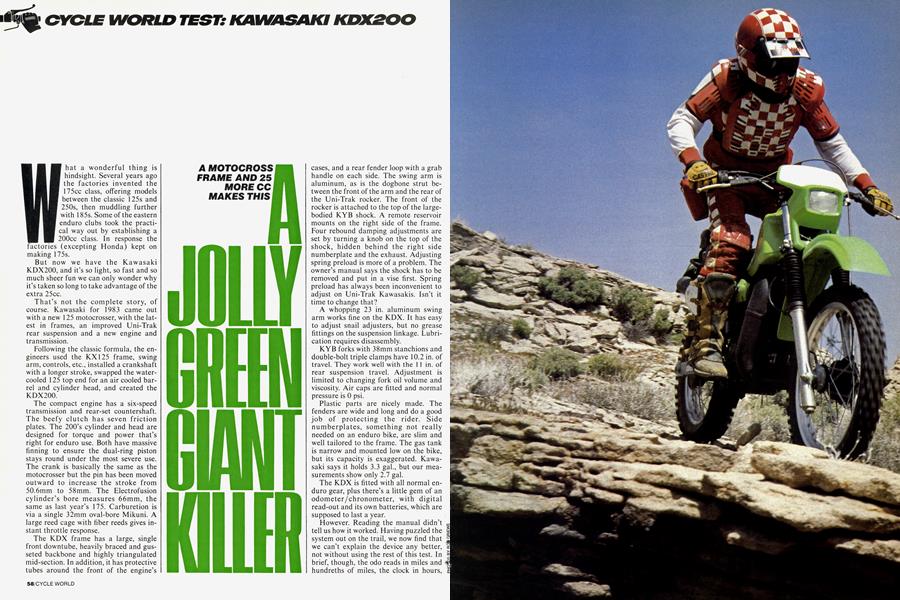

A MOTOCROSS FRAME AND 25 MORE CC MAKES THIS A JOLLY GREEN GIANT KILLER

What a wonderful thing is hindsight. Several years ago the factories invented the 175cc class, offering models between the classic 125s and 250s, then muddling further with 185s. Some of the eastern enduro clubs took the practical way out by establishing a 200cc class. In response the factories (excepting Honda) kept on making 175s.

But now we have the Kawasaki KDX200, and it’s so light, so fast and so much sheer fun we can only wonder why it’s taken so long to take advantage of the extra 25cc.

That’s not the complete story, of course. Kawasaki for 1983 came out with a new 125 motocrosser, with the latest in frames, an improved Uni-Trak rear suspension and a new engine and transmission.

Following the classic formula, the engineers used the KX125 frame, swing arm, controls, etc., installed a crankshaft with a longer stroke, swapped the watercooled 125 top end for an air cooled barrel and cylinder head, and created the KDX200.

The compact engine has a six-speed transmission and rear-set countershaft. The beefy clutch has seven friction plates. The 200’s cylinder and head are designed for torque and power that’s right for enduro use. Both have massive finning to ensure the dual-ring piston stays round under the most severe use. The crank is basically the same as the motocrosser but the pin has been moved outward to increase the stroke from 50.6mm to 58mm. The Electrofusion cylinder’s bore measures 66mm, the same as last year’s 175. Carburetion is via a single 32mm oval-bore Mikuni. A large reed cage with fiber reeds gives instant throttle response.

The KDX frame has a large, single front downtube, heavily braced and gusseted backbone and highly triangulated mid-section. In addition, it has protective tubes around the front of the engine’s cases, and a rear fender loop with a grab handle on each side. The swing arm is aluminum, as is the dogbone strut between the front of the arm and the rear of the Uni-Trak rocker. The front of the rocker is attached to the top of the largebodied KYB shock. A remote reservoir mounts on the right side of the frame. Four rebound damping adjustments are set by turning a knob on the top of the shock, hidden behind the right side numberplate and the exhaust. Adjusting spring preload is more of a problem. The owner’s manual says the shock has to be removed and put in a vise first. Spring preload has always been inconvenient to adjust on Uni-Trak Kawasakis. Isn’t it time to change that?

A whopping 23 in. aluminum swing arm works fine on the KDX. It has easy to adjust snail adjusters, but no grease fittings on the suspension linkage. Lubrication requires disassembly.

KYB forks with 38mm stanchions and double-bolt triple clamps have 10.2 in. of travel. They work well with the 11 in. of rear suspension travel. Adjustment is limited to changing fork oil volume and viscosity. Air caps are fitted and normal pressure is 0 psi.

Plastic parts are nicely made. The fenders are wide and long and do a good job of protecting the rider. Side numberplates, something not really needed on an enduro bike, are slim and well tailored to the frame. The gas tank is narrow and mounted low on the bike, but its capacity is exaggerated. Kawasaki says it holds 3.3 gal., but our measurements show only 2.7 gal.

The KDX is fitted with all normal enduro gear, plus there’s a little gem of an odometer/chronometer, with digital read-out and its own batteries, which are supposed to last a year.

However. Reading the manual didn’t tell us how it worked. Having puzzled the system out on the trail, we now find that we can’t explain the device any better, not without using the rest of this test. In brief, though, the odo reads in miles and hundreths of miles, the clock in hours, minutes and seconds. You get a button to report distance or time, but they don’t light up at the same time. Distance can be set forward or backward (always needed on enduros because the club’s mileage never agrees with yours) but the time can only be turned on, or off, at which point the clock goes to zero and begins anew. A good idea that needs work.

Hubs and wheel assemblies are small and compact. The spokes make tight bends as they exit the hub, and they loosen a lot on the first ride. The rear hub is much smaller and quite a bit lighten than before. The rear brake rod has Kawasaki’s version of Yamaha’s quick release, except it’s more difficult to use. Still, it’s faster than the ones where the wing nut has to be completely screwed off to release. The headlight/numberplate is a neat design with a dim 25\$ bulb. The on/off switch has been moved so it no longer extends to where tree limbs can prune it off. A tool bag made of thin, cheap-looking material bolts to the top of the rear fender. The rubber lever covers also look flimsy and they tear easily. No provision is made for a center stand. Those protective raifl around the front of the cases don’t offer enough protection to the engine. The bottom of the cases are exposed enough to stick a rock through. Also, the pipe’^, routed too low. Watch those big rocks and logs or you’ll smash it shut. The shift lever has a folding tip, the rear brakï* pedal doesn’t.

The airbox is typical of current UniTraks; it’s on the left side of the bike, with a filter that’s large in diameter but thin. Getting to it requires the removal of the left side numberplate, (two screws), and another three screws that secure the airbox cover. Not good on an enduro bike. The cover has four large air inlets and the top of the box has another two. Use in wet areas requires taping over the cover holes.

KAWASAKI

KDX200

$1649

The KDX200 has a wonderfully low seat height for a modern, long suspension dirt bike. It measures a little over 36 in. unloaded, which means it’s more like 33 in. with rider aboard. Everything is shaped and positioned so the rider doesn’t have to search for controls and the seat is very comfortable. The bars are a little close to the rider if he is forward on the seat, just like the other dirt bikes from Kawasaki. Still, smaller riders usually ride the 200s and most of our smaller riders were comfortable.

Starting isn’t to be feared either; one kick, hot or cold, normally does it. Warm-up is rapid and the gearbox drops into first without complaint. Shifting is smooth and precise. No one remembered missing any shifts. Shifting is something most 200cc riders do a lot of, although the KDX’s power and torque eliminate much of the shifting one usually associates with the small enduro class.

Beginner to Expert were impressed by the power and general handling. Even deep sand and freshly plowed fields have little effect on the tiny engine. One automatically expects the engine to start bogging as higher gears are selected, but the engine just keeps pulling. The power has to be experienced before it’s believed. Sixth gear sandwashes, even uphill ones, are no problem. If you really want to humble your buddy on his 250 enduro, challenge him in an uphill sandwash. The KDX200 can do it.

If the guy on the larger bike still feels cocky, head for some really tight brush or woods: you’ll probably be so far ahead of him he’ll think he’s been riding alone. The little KDX is so nimble and quick through the tight stuff it’s almost like cheating. And don’t worry about creek crossings, even deep ones. We forded some that were over our boot tops. The engine never misfired and the brakes never varied. They stopped as well, with as much feel, as before the water.

Gas consumption could be a problem. The bike uses a lot of gas to produce the power and torque. A novice can only get around 50 to 60 mi. per tank, an expert 40 to 50 mi., depending on terrain.

When the trail becomes littered with whoops and cross-gulleys, just smile and turn the throttle to its stop. The bike is arrow-straight through such terrain.

So far it doesn’t sound as if we had any complaints. But we found a couple of things to grumble about: First, the clutch has an in/out action. First-time riders stalled the engine at least once before getting under way. After a start or two no one was particularly bothered by it. And the quick-release clutch is an advantage when blasting through tight woods, especially if the trail has slight berms. Running deep into the turn, the rider can fan the clutch instead of downshifting and the bike responds by leaping out of the turn. Fast riders do it all the time, beginners not so often. The in/out action makes things difficult if you’re behind clumps of bogged-down riders on the side of a hill though. Trying to pick your way through such a mess takes finesse and a more progressive clutch action. The KDX is more than a handful under these conditions. The sudden clutch action lets the rear wheel spin madly and if it does hook up, it’s so sudden the bike loops.

The second complaint involves the engine’s overly demanding nature during break-in.

Not to put too fine a point on it, the piston sticks. Ours seized three times. During the test period we were in an enduro and pitted next to a man who’d just bought a KDX200 that seized a few miles into the first paved section. He was mad as hops, with reason: he’d saved for three years to buy the bike, takes it out for the first time then zap, stuck solid.

A careful postmortem made things look better, for us if not the new owner. All four seizures occurred when the bikes were being ridden by novices. All four came when the engine was under light load, as in cruising on pavement or after the throttle had been shut for a corner.

Two-strokes are sensitive about these things. Backing off the throttle cuts off the supply of cooling fuel and oil, and if the engine is only marginally cooled, it can seize.

This is a problem on the KDX200 because the engine is so highly tuned. It can develop a lot of heat. The coated aluminum cylinder should expand at the same rate as the aluminum piston and it should transfer lots of heat, so the clearances are tight. In our case, a Kawasaki wrench checked over the engine, sanded down the high spots on the piston and pronounced the problem solved. We’ve run it hundreds of miles since, with no repeats.

We’d suggest attentive and enthusiastic break-in. Odd though it sounds, a two-stroke is less likely to seize going full throttle up a sandwash, where the greater drag slows the engine speed and the fuel is mostly supplied by the main jet. Run it on pavement at the same speed, and zap. It’s stuck. Sand the high spots off the piston after 100 mi. and you’ll have no further worries.

In any case, we wouldn’t let this stop us from buying a KDX200. In fact, one of the riders who seized ours has since gone to the local dealer and bought one.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

August 1983 -

Letters

LettersCycle World Letters

August 1983 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

August 1983 -

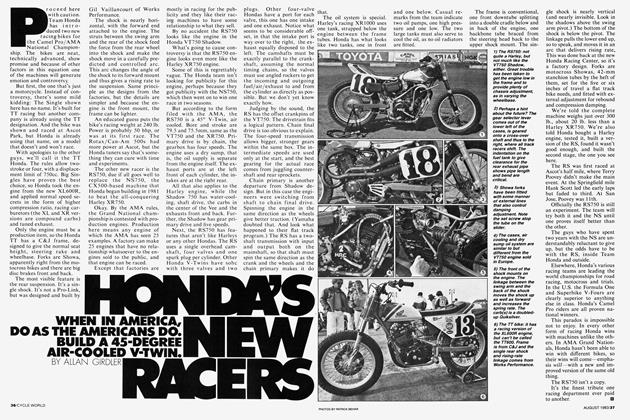

Competition

CompetitionHonda's New Racers

August 1983 By Allan Girdler -

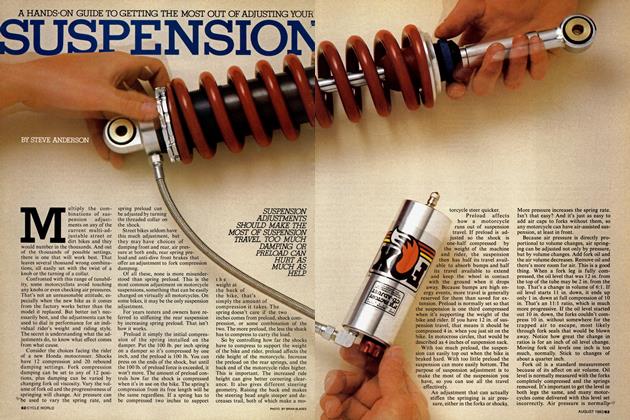

Technical

TechnicalA Hands-On Guide To Getting the Most Out of Adjusting Your Suspension

August 1983 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesParis-Dakar

August 1983 By Patrick Behar