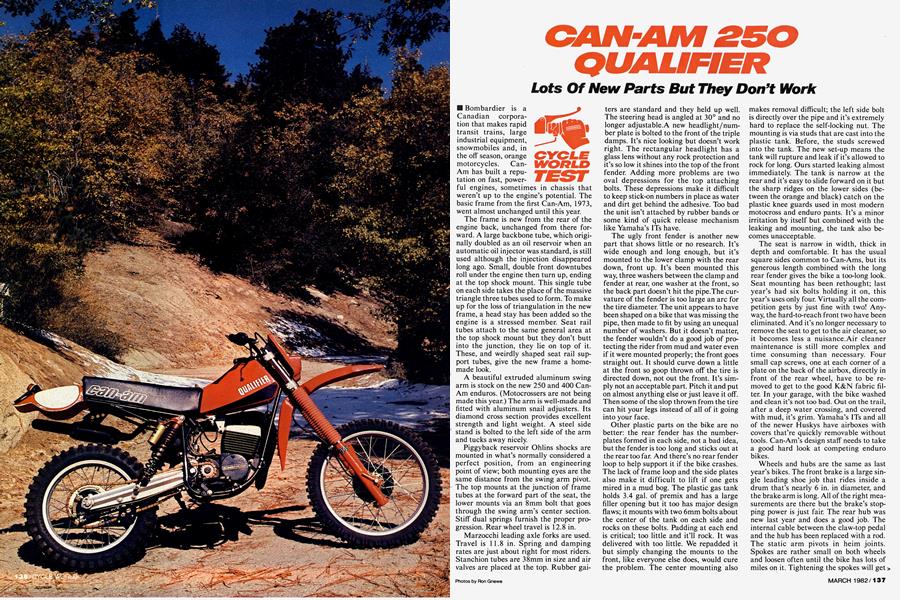

CAN-AM 250 QUALIFIER

Lots Of New Parts But They Don’t Work

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Bombardier is a Canadian corporation that makes rapid transit trains, large industrial equipment, snowmobiles and, in the off season, orange motorcycles. CanAm has built a reputation on fast, powerful engines, sometimes in chassis that weren’t up to the engine’s potential. The basic frame from the first Can-Am, 1973, went almost unchanged until this year.

The frame is new from the rear of the engine back, unchanged from there forward. A large backbone tube, which originally doubled as an oil reservoir when an automatic oil injector was standard, is still used although the injection disappeared long ago. Small, double front downtubes roll under the engine then turn up, ending at the top shock mount. This single tube on each side takes the place of the massive triangle three tubes used to form. To make up for the loss of triangulation in the new frame, a head stay has been added so the engine is a stressed member. Seat rail tubes attach to the same general area at the top shock mount but they don’t butt into the junction, they lie on top of it. These, and weirdly shaped seat rail support tubes, give the new frame a homemade look.

A beautiful extruded aluminum swing arm is stock on the new 250 and 400 CanAm enduros. (Motocrossers are not being made this year.) The arm is well-made and fitted with aluminum snail adjusters. Its diamond cross section provides excellent strength and light weight. A steel side stand is bolted to the left side of the arm and tucks away nicely.

Piggyback reservoir Ohlins shocks are mounted in what’s normally considered a perfect position, from an engineering point of view; both mounting eyes are the same distance from the swing arm pivot. The top mounts at the junction of frame tubes at the forward part of the seat, the lower mounts via an 8mm bolt that goes through the swing arm’s center section. Stiff dual springs furnish the proper progression. Rear wheel travel is 12.8 in.

Marzocchi leading axle forks are used. Travel is 11.8 in. Spring and damping rates are just about right for most riders. Stanchion tubes are 38mm in size and air valves are placed at the top. Rubber gaiters are standard and they held up well. The steering head is angled at 30° and no longer adjustable.A new headlight/number plate is bolted to the front of the triple damps. It’s nice looking but doesn’t work right. The rectangular headlight has a glass lens without any rock protection and it’s so low it shines into the top of the front fender. Adding more problems are two oval depressions for the top attaching bolts. These depressions make it difficult to keep stick-on numbers in place as water and dirt get behind the adhesive. Too bad the unit isn’t attached by rubber bands or some kipd of quick release mechanism like Yamaha’s ITs have.

The ugly front fender is another new part that shows little or no research. It’s wide enough and long enough, but it’s mounted to the lower clamp with the rear down, front up. It’s been mounted this way, three washers between the clamp and fender at rear, one washer at the front, so the back part doesn’t hit the pipe.The curvature of the fender is too large an arc for the tire diameter. The unit appears to have been shaped on a bike that was missing the pipe, then made to fit by using an unequal number of washers. But it doesn’t matter, the fender wouldn’t do a good job of protecting the rider from mud and water even if it were mounted properly; the front goes straight out. It should curve down a little at the front so goop thrown off the tire is directed down, not out the front. It’s simply not an acceptable part. Pitch it and put on almost anything else or just leave it off. Then some of the slop thrown from the tire can hit your legs instead of all of it going into your face.

Other plastic parts on the bike are no better: the rear fender has the numberplates formed in each side, not a bad idea, but the fender is too long and sticks out at the rear too far. And there’s no rear fender loop to help support it if the bike crashes. The lack of frame loop and the side plates also make it difficult to lift if one gets mired in a mud bog. The plastic gas tank holds 3.4 gal. of premix and has a large filler opening but it too has major design flaws; it mounts with two 6mm bolts about the center of the tank on each side and rocks on these bolts. Padding at each end is critical; too little and it’ll rock. It was delivered with too little. We repadded it but simply changing the mounts to the front, like everyone else does, would cure the problem. The center mounting also makes removal difficult; the left side bolt is directly over the pipe and it’s extremely hard to replace the self-locking nut. The mounting is via studs that are cast into the plastic tank. Before, the studs screwed into the tank. The new set-up means the tank will rupture and leak if it’s allowed to rock for long. Ours started leaking almost immediately. The tank is narrow at the rear and it’s easy to slide forward on it but the sharp ridges on the lower sides (between the orange and black) catch on the plastic knee guards used in most modern motocross and enduro pants. It’s a minor irritation by itself but combined with the leaking and mounting, the tank also becomes unacceptable.

The seat is narrow in width, thick in depth and comfortable. It has the usual square sides common to Can-Ams, but its generous length combined with the long rear fender gives the bike a too-long look. Seat mounting has been rethought; last year’s had six bolts holding it on, this year’s uses only four. Virtually all the competition gets by just fine with two! Anyway, the hard-to-reach front two have been eliminated. And it’s no longer necessary to remove the seat to get to the air cleaner, so it becomes less a nuisance.Air cleaner maintenance is still more complex and time consuming than necessary. Four small cap screws, one at each corner of a plate on the back of the airbox, directly in front of the rear wheel, have to be removed to get to the good K&N fabric filter. In your garage, with the bike washed and clean it’s not too bad. Out on the trail, after a deep water crossing, and covered with mud, it’s grim. Yamaha’s ITs and all of the newer Huskys have airboxes with covers that’re quickly removable without tools. Can-Am’s design staff needs to take a good hard look at competing enduro bikes.

Wheels and hubs are the same as last year’s bikes. The front brake is a large single leading shoe job that rides inside a drum that’s nearly 6 in. in diameter, and the brake arm is long. All of the right measurements are there but the brake’s stopping power is just fair. The rear hub was new last year and does a good job. The internal cable between the claw-top pedal and the hub has been replaced with a rod. The static arm pivots in heim joints. Spokes are rather small on both wheels and loosen often until the bike has lots of miles on it. Tightening the spokes will get > a preacher cursing; the nipples are as soft as lead and strip easily even with a wide spoke wrench. Rims and tires are the high point of the Can-Am wheel assemblies. Tires are excellent Dunlop models; K139 front, K190 rear. Sun rims with rim pins are great.

The Rotax engine has been around for several years now. It has proven strong and reliable. Six speeds are in the tidy cases. Past 250s have used Bing carbs, the ’82 has a Mikuni. The carb mounts low on the left side of the center cases and fuel is routed to the cases through a flat rotary valve. The cylinder has wide fins that provide excellent cooling. Porting is the same as previous enduro Can-Ams. No trick boost ports like the later motocross CanAms used, just normal stuff. The kick and shift lever are on a combined shaft; the shift shaft goes through the center of the kick shaft. The left side kick lever has good leverage and the engine is easy to kick over.

Control levers and cables are a combination of good, poor and junk. Levers are good Magura dog-leg models, grips are fine, as are the bars. The throttle, made by Can-Am, offers two speeds— quarter turn and half turn. The change over is simple and quick but the unit turns so hard when the quarter turn is selected your forearm is soon exhausted. Even in the half turn position the throttle is too stiff and the cable extends the way all cables did five years ago. Snagging a tree limb is a real possibility.

Better go and pump some weights before attempting the clutch lever on a CanAm 250. The pull is ridiculously hard. It becomes almost impossible for most people to pull more than three or four times in a row. Throwing away the stock cables and replacing them with nylon-lined Terry Cables helps a bunch, but the hard pulling clutch soon wears any cable out.

Memories of past 250 Can-Ams had us expecting a powerful, torquey engine. Ours, at least, was a disappointment. Holding the throttle wide open and constant shifting was the only way it would outrun a fast 10-speed bicycle! We spent almost a day trying to jet and tune the bike. The carburetor needle ended up in the highest position. Between 4000 and 6000 ft. the bike got faster with the raised needle but it still lacked the quickness and responsiveness of past Can-Ams. Sliding a corner or lofting the front tire with engine power was out of the question. We called the factory the next day and asked about engine changes. None, except for the Mikuni and pipe was the answer. And they claimed the changes were responsible for a 1.5 horsepower boost. We checked timing, crank seals, and air cleaner. All okay. Next we checked the tunnel backbone for obstructions. Nope, everything okay. We never did get the engine to run where it made much power.

Major problems with the new chassis surfaced on the first ride. The steering head angle is set at 30° and the wheelbase is over 57 in. Not bad geometry for the desert. But the bike doesn’t work in the woods. Turning on tight trails is terrible. The bike wants to go straight. It takes a lot of rider effort to make anything more than a sweeping turn. Lots of muscle and determination and hope. Add bumps before the turn and the stiff shock springs make the rear of the bike dance and buck and the bike goes straight out through the trees. What a shame. Nearly 13 in. of rear wheel travel and only half of it usable unless you weigh 250 lbs. Trying to turn the bike in a bermed motocross or late-number enduro corner, the front wheel starts through, the back continues going straight. We asked the factory for some of the older adjustable steering head bearings, and some softer shock springs. The parts weren’t here six weeks later so we gave up trying to make it ridable.

CAN-AM

250 QUALIFIER

$2199

Even if these things worked, the bike has some annoying design problems. The shocks angle in at the top to make the middle of the bike narrower but their width is wider than the seat. And the Bosch coil is

mounted partly outside the frame where the rider’s leg rubs on it. Plastic covers over the shock tops would stop that complaint. The placement of the coil is stupid. Even a novice mechanic could find a better place for it. There’s lots of room in the center of the chassis or maybe it could go into the big hole up under the gas tank, like everyone else does it. Better wear motocross pants with knee guards when riding the new bike, while the right leg is dragging on the coil, the left one is hitting the pipe.

All in all the Can-Am 250 Qualifier is the most disappointing machine we’ve tested in quite some time. The new frame, aluminum swing arm, 38mm forks, Ohlins shocks and Rotax engine should add up to a super motorcyle. If they’d fix the rear suspension, rethink the fenders, tank, numberplate and a few other items and then figure out what in blazes they’ve done to what used to be a wonderful engine, the ’82 Can-Am could still be a super motorcycle.