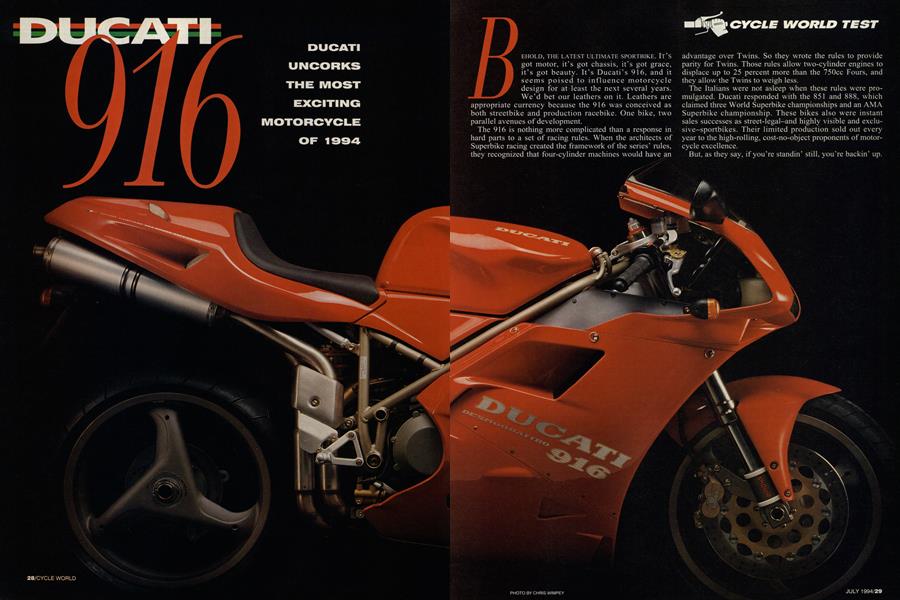

DUCATI 916

DUCATI UNCORKS THE MOST EXCITING MOTORCYCLE OF 1994

CYCLE WORLD TEST

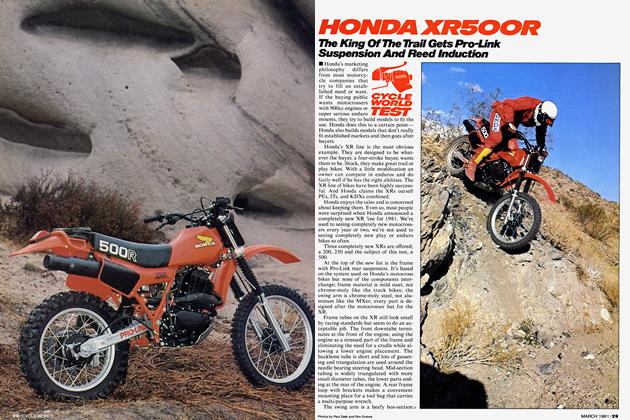

EHOLD, THE LATEST ULTIMATE SPORTBIKE. IT’S got motor, it’s got chassis, it’s got grace, it’s got beauty. It’s Ducati’s 916, and it seems poised to influence motorcycle design for at least the next several years. We’d bet our leathers on it. Leathers are appropriate currency because the 916 was conceived as both streetbike and production racebike. One bike, two parallel avenues of development.

The 916 is nothing more complicated than a response in hard parts to a set of racing rules. When the architects of Superbike racing created the framework of the series’ rules, they recognized that four-cylinder machines would have an advantage over Twins. So they wrote the rules to provide parity for Twins. Those rules allow two-cylinder engines to displace up to 25 percent more than the 750cc Fours, and they allow the Twins to weigh less.

The Italians were not asleep when these rules were promulgated. Ducati responded with the 851 and 888, which claimed three World Superbike championships and an AMA Superbike championship. These bikes also were instant sales successes as street-legal-and highly visible and exclusive-sportbikes. Their limited production sold out every year to the high-rolling, cost-no-object proponents of motorcycle excellence.

But, as they say, if you’re standin’ still, you’re backin’ up.

The Italians were not standing still. With Japanese Superbike teams becoming more and more competitive, Ducati began developing a not-quite all-new Superbike contender. Hints about the bike’s form began leaking out of Ducati’s Bologna factory, and Cagiva’s San Marino technical-development center, four years ago. First there was word of an aluminum twin-spar frame, an idea tested but discarded because the men who guide the company’s fortunes regard the chrome-molybdenum steel tube frame as a Ducati signature. Next was word of a singlesided swingarm. Of this, one highly placed factory insider two years ago told Cycle World, “Nope, couldn’t be. If they were working on that, we’d be testing it on my racebike.”

What Ducati was working on was not just a development of the 851/888, but a new motorcycle. After some fits and starts caused by internal politics, the decision was taken to have the bike online for the 1994 model year-it’ll be an early-release ’95 in the U.S. It may be a new design, but it is essentially Ducati, remaining true to all that is endearing, and enduring, about the marque.

What is familiar about the 916 is its engine and slickshifting six-speed transmission, a development of the original 851 power unit. The engine now displaces 916cc and uses a compression ratio of 11.0:1 to produce 105 rearwheel horsepower at 9000 rpm. Its bore is the same used in the 888-94mm. The increased capacity comes from an additional 2mm of stroke, bringing that measurement to 66mm.

What enters the 916’s combustion chambers via two intake valves per cylinder must be evacuated as spent gases by each cylinder’s pair of exhaust valves. Flow of these gases is handled by a stainless-steel 2-into-2 exhaust system whose twin tubes sweep upward, just aft of the rear cylinder, and into the area under the bike’s tailsection, where elliptical canisters tame the engine’s bark. That silencer location isn’t just the result of a stylist’s design; it gets the canisters out of the airflow and materially reduces the bike’s coefficient of drag.

A revised and enlarged airbox works to help fill the engine’s increased capacity. Earlier Ducatis used a separate plastic unit that lived under the fuel tank, but the 916’s airbox is composed of several unlikely bits. The first is a molded plastic tray bolted to the frame rails to help stiffen the frame. The box is completed by the bottom contours of the fuel tank, which comprise the top and sides of the airbox. This is fed by twin scoops below, and slightly outboard of the bike’s twin headlamps. Each of these scoops uses its own foam air filter.

The 916’s engine-management system, which encompasses a fuel-injection setup that feeds one injector per cylinder, has been revised and remapped, with its central processing unit rubber-mounted under the bike’s tailsection. This opens forward on hinges mounted just aft of the fuel tank to reveal not only the CPU, but also tool-kit storage and a helmet lock.

The 916’s engine may be a familiar piece of engineering, but the rest of the bike is completely new. That newness starts with the frame designed to provide service ease. Where Ducati’s older Superbikes used one-piece frames, the 916 uses a two-piece assembly, with the main chrome-moly unit carrying a boltedon aluminum rear subframe. That means a crash-damaged frame no longer is necessarily a throw-away item. There’s another notable change. Older Ducati swingarms mounted to pickup points in the engine cases. The 916 retained those engine-case pickup points, but doubled them with concentric frame pickup points, thereby increasing chassis stiffness.

While designer Massimo Tamburini was figuring all this out, he went out of his way to centralize the 916’s mass. With the exception of the headlight and CPU, everything that makes the 916 work is centralized around the engine, which was rotated forward 1.5 degrees to allow for the front-tire-to-cam-cover clearance the 916’s compact wheelbase requires. Even the coolant container is deployed between the steering head and the airbox, and the auxilary coolant-expansion tank is down in the vee of the engine. Such mass centralization allowed Tamburini to give the bike a 55.5-inch wheelbase, .8-inch shorter than the 888’s. The effect is that of sliding the weights on a barbell to the center of the bar, and results in what’s called a low polar moment of inertia. It means that the device-barbell or motorcycle-can change directions much more quickly than it could if all its weight was deployed toward its ends. The 916’s weight distribution nevertheless mimics racing practice-49 percent of the bike’s 438 pounds is on its front wheel.

Further testimony of this bike’s racing heritage and intent is found in the fact that the radiator/engine/transmission can be dropped out of the chassis as a unit, without draining, the cooling system. Think that might be an aid to rapid trackside engine changes?

The 916’s swingarm is part of what gives the bike its distinctive style-it’s a single-sided unit that gets around the ELF/Honda patent on such designs by being different in at least three areas of detail. It’s not only pretty, it also is 50 percent more torsionally rigid than the 888’s double-sided

swingarm, according to Ducati. Chain adjustment is accomplished via an eccentric hub, and the wheel rotates on a combination of roller and ball bearings. Why a single-sided swingarm? Here’s a clue: For 1994, the World Endurance Championship will use equipment built to the same rules that shape World Superbike equipment. Quick rear-tire changes are important in endurance racing.

Rear suspension is handled by a Showa shock with a remote reservoir and the three usual adjustment parameters. The top of the shock is linked to the rear of a rocker that connects, at its forward point, to the top of a ride-height adjustment rod. The rocker’s pivotpoint is mounted to the bike’s frame, and the entire rear-suspension linkage system operates on roller bearings and steel-and-teflon ball joints. The shock’s damping is quite soft and adjustment range for the screw-type compression and rebound damping is narrow-2.25 turns for compression and 1.75 turns for rebound-providing the first suggestion of a component that demanding riders will upgrade.

Up front, the triple-tapered and beautifully finished Showa fork offers 1.5 centimeters of preload adjustment-about .6inch, for those of you who are metrically challenged-as well as 13 clicks-worth of rebound-damping adjustment and 18 clicks of compression damping. The shock and fork aren’t the only Japanese components on the 916. Also from Japan is the DID chain-and, probably, the handlebar switchgear, which has a very Honda-like look. Something else, though, comes not from Japan, but straight from the Cagiva Racing Department: steeringgeometry changes via an elliptical adjuster in the steering head. The range is from 24 to 25 degrees, the steeper angle providing 3.7 inches of trail, and the shallower angle providing 3.94 inches. A clever steering-damper arrangement mounts the damper across the chassis, just forward of the fuel tank. The damper does its job well enough, but as Cycle World accumulated miles aboard the 916 and the fuel tank began moving around on its mounts, the damper body began contacting the front of the tank and eventually scuffed through the paint.

The front wheel is the standard aluminum unit, 3.5-inches wide, carrying a 120/70-17 Michelin TX11. The 5.5-inch-wide rear wheel carries a significant escalation of the sportbike tire wars-a super-wide 190/50-17 Michelin TX23. As hard as we used the bike during testing on the street and at the track, we never got all the way to the edge of this tire. Brakes are as on Ducati’s 888s—up front, a pair of 12.6-inch steel rotors gripped by Brembo calipers using differentially sized pistons. At the rear, there’s an 8.7-inch rotor using a two-piston caliper.

A review of the 916’s hard parts does little to prepare one for the bike in-the-flesh. It’s an Armani suit on wheels, a bike that immediately draws crowds whenever it is parked. Remind you of the Ducati Supermono? It should. The Supermono’s styling grew from the 9l6’s design. The bike’s beautifully integrated headlamps are particularly notable-they rely on a very Euro elliptical low-beam unit on the left and a high-beam element on the right. The overall level of finish is high, marred only by poor-quality rivets that hold the two-piece fairing together-after a day at the racetrack, our 916 lost half its complement. We’d also like to see harder clear-coat applied to the 916’s sexy red bodywork; as it is, even a careful swipe of a polishing rag leaves scratches. Otherwise, the 916 is as stunning close-up as it is in photographs.

Well, so what? The bike is beautiful and full of clever, forward-thinking ideas. But does it work? Does all that careful engineering pay off?

Throw a leg over the 916 and the first thing that you see is that it’s quite a small bike, and, like the Supermono, very narrow in the waist. In spite of that, its ergonomics provide room for a wide range of rider sizes, with a surprising amount of space for taller riders. Twist the ignition key and thumb the beast into life, and you’re rewarded with nothing more neighbor-annoying than a well-muffled thrum from the oval canisters. Don’t be put off. There’s plenty of life behind that quiet whir. The 916 has benefited greatly from the development given the engine-management system, as it not only starts and runs from cold without complaint, but delivers far more pulling power at all rpm than any stock Ducati Cycle World has tested.

Usable power begins at about 3500 rpm and continues right to the engine’s 10,200-rpm rev limit, which is where the engine-management system cuts off spark. The power on tap is vast and linear, and is delivered as though the throttle grip is a rheostat. Want a bit, turn the grip a bit. Want more, turn the grip more. There’s nothing peaky about this engine. It not only lifts the front wheel off the pavement at the slightest flick of the wrist, it also feels strong enough to pull a string of box-cars. In quarter-mile testing, the 916 stopped the clocks in 10.72 seconds at 130.62 mph. That time is quicker than 750cc inline-Fours, and the trap speed puts the Ducati in the Kawasaki ZX-1 1 ’s league. For those still not satisfied, there’s this news: A high-performance version of the 916, using an upgraded version of the SP5 engine, is on the way. Its engine is rated at 131 crank horsepower at 10,700 rpm. Bring money.

Get the bike out on the straight-and narrow, on the way to your favorite sport-riding roads, and you find that the riding position is only a little more aggressive than that required by the 888. It is adjustable only in that the clip-on bars can be moved down the fork tubes. At their top position, they are indexed into the only position that will keep them from contacting the fairing and fuel tank at full lock. Even so, the 916 has more steering lock than the 888.

Once on your favorite backroad, you’ll find the steering so light and so neutral, and so eager to respond to rider input, that it’s almost intuitive. Side-to-side quickness is better than that delivered by the 888, with flick-in requiring much less countersteer effort than that bike. The engine’s huge torque production is so capable of exploding the bike out of comers and devouring straightaways that to take full advantage of its capabilities, you have to recalibrate the part of your brain that calculates time and distance. It doesn’t matter how well you know your favorite road, or what you ride there; the 916 is likely to make its straights shorter and its comers narrower. These characteristics make the 916 very easy to ride, and very easy to ride fast. It’s pretty good at the racetrack, too, circulating Willow Springs Raceway under the control of CW tester and World Endurance Champion Doug Toland in 1:31.14, three-tenths of a second quicker than his best time aboard Ducati’s 888, winner of last month’s Supersport Shootout.

Even better lap times are likely if the shock is upgraded to match the fork. The latter is a terrific piece of work that is so responsive and rigid that you feel as though the clip-ons are connected straight to the front axle, providing excellent feedback from the front tire’s contact patch. But for hard riding, the shock is underdamped, even with rebound and compression adjusters cranked up to full-hard. On the racetrack, it allowed the bike to move around far too much for anyone’s taste. Whether we got a bad shock, or whether-as one tester theorized-the shock’s position immediately adjacent to the upswept exhaust pipes causes overheating, were unanswerable questions within this test’s time frame.

The windscreen also is a problem. When the rider is tucked-in, the screen’s Euro-flip, that turned-up section at its trailing edge, badly distorts the rider’s vision. Testers found themselves lifting their heads up over the screen to see where they were going. The brakes also got some negative comment. For street use, they provide plenty of feel and power, but on the track, there’s a bit too much lever travel. Additionally, we found that rocks thrown up by the front tire dinged the oil radiator’s vanes, bending them closed. Not good. Would a big-enough stone punch a hole in this critical component, mounted right down there in the fairing’s chin? Maybe. We don’t want to be aboard when it happens. Some grillwork over this radiator would solve the problem. And finally, there’s that springloaded sidestand. Selfretracting stands are required in some European countries, but if the 916 was ours, we’d defeat this one.

As a whole, though, the 916 is an open invitation to enjoy state-of-the-art motorcycle thinking, engineering, design and performance, and Ducati apparently is serious about its invitation. Just 50 Honda RC45s are expected to be brought to the U.S. this year, at a price of $27,000 each. Counter that with 400 916s coming to the U.S.-of the total production run of 4000. All those U.S. bikes will carry list prices of $14,500, a thousand bucks more than last year’s 888. You don’t have to be a genius to figure out that anyone who cares about exotic motorcycles will find this a screaming deal.

Even so, the 916 isn’t inexpensive, and it isn’t perfect. Spending its purchase price requires more than a little commitment, and the bike has a few remaining detail zits that always seem to be part of the character of Italian motorcycles. But in spite of its price and in spite of its minor flaws, the 916 is one extremely rewarding motorcycle. □

DUCATI 916

SPECIFICATIONS

List price $14,500

EDITORS' NOTES

WHILE RIDING THE 916 I’VE HAD SEVERal people inquire about the bike’s cost. Each time, I’m amazed at my own reply. “It’s really not that expensive, only $14,500,” I tell them.

Whoa! What’s happened to me? Maybe I’ve been in L.A. too long. Maybe $45 USGP tickets and $7000 600cc sportbikes have reshaped my sense of value. Well, sure, but what really makes the 916 seem such a bargain is its ultra-exotic appearance. And this styling, capable of making a Bimota owner drool, isn’t the only thing the new Ducati brings to the table.

Think of the 916 as an Italian equivalent of Honda’s CBR900RR. Out of the crate, both bikes weigh within a few pounds of one another, top out at 157 mph, run nearly neck-and-neck through the quarter-mile and circulate the Willow Springs road course within a second of each other (the Duck’s a little quicker).

(the Duck’s a little quicker). The difference? A CBR rings-in about $5500 less. I believe my senses have just been brought back into perspective. -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

AT FIRST GLANCE, YOU MIGHT THINK Ducati’s latest work of art should make its home in a gallery rather than a garage. From the subtle sweep of the swingarm to the delicate dimensions of the headlamps, this bike can be admired for its style alone.

But the second you swing a leg over the slim seat, any thought that the 916 should pose on a pedestal in some

Italian museum is immediately forgotten. Its true beauty is best displayed on the street, where the Ducati’s substance is as rich as its racy red paint.

Of course, not even the 916 is perfect. As I painfully learned after 70 miles on Interstate 5, a lengthy straight-line ride aboard the 916 leaves hands numb, butt sore and legs cramped (and I’m just 5 feet, 4 inches tall!). But even considering that complaint, if I were lucky enough to actually own one, you can be sure the 916 would be right where it belongs: not in a gallery, nor a garage, but on a sweet (if-for comfort’s sake-short) stretch of road.

-Brenda Buttner, Feature Editor

THIS MOTORCYCLE MAKES PEOPLE NUTS. Riding it definitely makes you nuts, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Neither is what happens when you stop at your favorite mid-ride burger joint, and it immediately empties the place as other sport riders seize the opportunity to view their first 916. That part’s fun.

No, what I’m talking about is what happens when you haul the thing in the back of your pickup, like I did on the way to and from studio photo sessions. People run you off the road as they try and get close enough to navigate at 75 mph (yep, that’s life on SoCal’s freeways) while cadging a glimpse of the 916’s voluptuous details. When you consider the invaluable exposure this thing received while being hauled around in the back of my poor old beater Mazda, and the resulting risks to my personal well-being and peace-of-mind-well, I think the decent thing would be for Cagiva North America to give me a 916 for my trouble. Don’t you? -JonF. Thompson, Senior Editor