DUCATI 600SL PANTAH

Italy’s Newest V-Twin is Dedicated to Sport, Pure and Simple, Creature Comforts and Urban Life Be Damned.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

There are times when riding a Ducati Pantah is magic, as when hurtling along a gently-curved, deserted highway, surrounded by fields of green spring grass, enveloped in a rush of warm air, the speedometer needle bent over hard right and the beat of the exhaust lost behind in the speed.

And there are times when riding a Ducati Pantah is a chore, as when bucking along a sagging section of concrete freeway in

heavy traffic, kidneys crying for support, wrists aching and locked at an odd angle, the engine stumbling and hesitating with each tiny movement of the twist grip.

There may be motorcycles that can’t make up their mind what they’re supposed to be or do, but the Pantah is not among them. The Pantah is a sport bike, built to run hard and fast and not to languish in the crush of urban congestion.

Its purpose is obvious from the first glance—the styling carries road racer looks beyond hints and suggestions into the Grand Prix world of fairings and clip-on handlebars and streamlined tailsections.

The Pantah carries Ducati’s latest engine, the most recent in a line of 90° V-Twins dating back to the late 1960s when the company lashed together two 250cc Singles to build a 500cc racebike. The original engine was enlarged and refined into a 750, the basis for the current 900s (which are actually 860cc). Throughout the evolution, the Ducati Vees sold to the public retained 40° (from vertical) valve angle, two valves per cylinder, roller-bearing crankshaft and sohc with each cam driven by a shaft and four bevel gears.

Ever-tightening government regulations—both in Europe and America—on allowable sound levels, the performance lessons learned in 13 years of racing the older Vees, and the high cost of producing the 900 engine all were major considerations in the design of the Pantah engine.

The new engine started with 498.9cc in the Pantah 500, with bore and stroke of 74 x 58mm. It was enlarged to the 583cc Pantah 600 by increasing bore to 80mm. It’s still a 90° aircooled V-Twin with sohc, two valves per cylinder and desmo valve gear (more on this later). But the Pantah has a plain bearing crankshaft and its camshafts are driven by toothed rubber belts, four sprockets and two belts replacing the shafts and gears used in the older engine. The belts are quieter and cheaper and have proven reliable in automotive (and Honda Gold Wing) applications.

Beyond the change in the type of camshaft drive, the desire to reduce noise shows up in the form of rubber pads partially surrounding the cam drive belt sprockets and in the placement of 60 individual rattle-damping rubber bushings between cylinder cooling fins.

The switch from the roller-bearing crankshaft of the 900s to the Pantah’s plain-bearing crankshaft made sense in several ways. The 900’s built-up roller bearing crankshafts were expensive to build, contributed to mechanical noise, and had a racing life measured in hours. The Pantah’s plain-bearing crank with two-piece rods and insert bearings is less expensive to make, runs quieter and has improved racing durability. It’s also lighter.

The Pantah crankshaft, like the crank used in the 900 engine, has a single throw carrying the two connecting rods side-by-> side. The rod for the front cylinder is to the right of the rod for the rear cylinder, so the front cylinder is offset to the right.

The Ducati’s 90° Vee is wider than most, gaining several advantages. A 90° V-Twin offers perfect primary balance, and allows plenty of room for the placement of carburetors and exhausts to best performance advantage. It’s also easier to cool the rear cylinder of a wider Vee. A disadvantage is that a 90° V-Twin is expensive to produce because the almosthorizontal front cylinder and head must be different castings than the rear cylinder to ensure that cooling fins match the direction of airflow. Another disadvantage is that—all other things being equal—wider V-Twin engines require a longer wheelbase than narrower Vees, again because the front cylinder is almost horizontal.

Like all V-Twins, the Ducati’s firing

order is staggered. If it were a parallel Twin, one cylinder would fire, and 360° of crankshaft rotation later, the second cylinder would fire. But because the cylinders are arranged 90° apart, the rear cylinder fires 270° (360° minus 90°) after the front cylinder, and the front cylinder fires again 450° (360° plus 90°) after the rear cylinder.

Experience gained in 13 years of campaigning the older Vees figures heavily in the design of the Pantah’s cylinder heads. The 900s were limited by intake port and combustion chamber shape, both related to the 900’s valve angle of 40° from vertical.

The Pantah, like the factory’s successful short-stroke racing 750 of the early ’70s, has a 30° valve angle and ports that drop into the combustion chambers. The valve angle allows a more compact combustion chamber and a lower piston dome for the 9.5:1 c.r., and the lower pis-

ton dome combines with the port shape to improve breathing.

The intake valves measure 37.5mm, the exhaust valves 33.5mm. The camshafts open the intake valves 50° BTDC and close them 80° ABDC; the exhaust valves open 75° BBDC and close 45° AT DC.

Ducatis have been sold with conventional valve springs and with desmodromic (desmo for short) valve gear, in which one rocker arm opens a valve, and a second rocker arm pulls it shut, each rocker arm activated by its own cam lobe, one cam lobe mirroring the other so as one arm rises the other falls and vice versa.

Desmo engines have become the unofficial trademark of Ducati, and the system was developed for racing long ago when poor valve spring quality led to problems with valve float and spring breakage. Because the valves in a desmo engine are mechanically closed instead of relying on spring pressure, valve float is impossible. In the desmo Pantah engine, there is a small, hairpin spring attached to each valve to positively seat the valve for starting, but that spring is of no consequence after start up.

The valve-closing rocker arm is forked and fits underneath a top-hat-shaped collar positioned below retainer clips on the valve stem. A winkler cap shim fits on top of the end of the valve stem, and the opening rocker arm pushes against the winkler cap. Clearances must be set for both rocker assemblies, and those clearances are adjusted by winkler caps and collars of different thicknesses.

It’s a clever system, but adjustment requires a fair amount of disassembly, including the removal of rocker arm shafts. The most time-consuming part of the job, experienced Ducati mechanics tell us, is sizing the shims on a surface grinder—the shims listed in the parts book don’t come in small enough increments to allow precise valve clearances. Fortunately, once broken in, many desmo Ducatis maintain correct opening and closing clearances over long periods of time, in some cases 10,000 mi. and beyond.

The rubber cam belts are driven off the right end of a shaft located between the cylinders. The other end of that shaft is gear driven off the left end of the crankshaft. The cams run in ball bearings pressed into the head castings.

The pistons used in the Pantah are forged and carry three rings, two compression and a one-piece oil control. The cylinders are aluminum without iron liners. Instead of using the usual pressed-in liners, the cylinder bores are chemically coated with a combination of nickel and a small percentage of ceramic silicon carbide particles. The nickel in the mixture holds the silicon carbide particles in place, and the particles themselves, which are only slightly less hard than diamonds, act as the wear surface. Because silicon carbide resists galling, the surface is less prone to seizure than either a chrome-plated bore or an iron bore. The surface is very durable, but if it is damaged, the entire cylinder must be replaced.

Primary drive is via helical gear and the conventional multi-plate clutch is operated hydraulically. The transmission has five speeds and the final drive sprocket is mounted directly on the countershaft. The drive chain is 530 non-Oring Diamond chain.

Each cylinder is fed by its own 36mm Dell’Orto with accelerator pump, and each carb draws air through a long rubber elbow running up to a single cylindrical airbox and pleated paper element. The ignition is inductive electronic using a Bosch control box and Nippondenso coils. Ignition advance is electronically controlled. There is an electric starter and no provision for kick start.

The Pantah has dual exhausts joined underneath the engine by a crossover tube/expansion box designed to increase mid-range power. Huge Conti mufflers eliminate most of the throaty V-Twin staggered exhaust beat.

The Ducati’s frame is built up of small tubes, the main structure formed like a bridge truss instead of the more common motorcycle frame using a single large backbone tube or a pair of tubes. The design originated in racing and is very rigid without being heavy. There is no engine cradle and no tubes run underneath the motor. The engine hangs below the frame, (a design also used by Yamaha) and is a stressed member. Two engine mount bolts are located between the cylinders, two behind the rear cylinder, and two more at the bottom rear of the crankcases, matching a set of rear section tubes extending from the main frame. The rear section tubes also carry upper mounts for the gas-charged Marzocchi shock absorbers.

The swing arm pivot shaft runs through the rear of the engine cases and is supported by two plain bushings located inside the cases and lubricated by engine oil. The steering head stem rides in tapered roller bearings.

Steering head rake is 30.5°, and wheelbase is 57 in. Wheels are cast magnesium, a WM3-18 front and a WM4-18 rear, and come mounted with a Michelin S41 front tire and a Michelin M45 rear tire.

The Pantah’s half fairing is made of fiberglass in two sections, bolted together across a central seam, with a plexiglass bubble windscreen. The fairing is mounted to the frame with a pylon mount running from the steering head (between the fork tubes) and a side mount bolted to the frame just above the front cylinder head. The front fairing mount also carries the quartz 55/60w headlight, the choke lever and the cabledriven Nippondenso speedometer and tachometer. A row of lights is positioned between the instruments, indicating lights and high beam turn signal use, neutral selection, loss of oil pressure, alternator failure, or sidestand deployment (although there isn’t a sidestand). The front turn signals are rectangular and built into the fairing on each side. The rear turn signals are round and mount on stalks from the rear fender.

Clip-on handlebars are positioned just below the upper triple clamp and carry Japanese electrical switches and Brembo master cylinders, one for the front brakes and one for the hydraulic clutch.

The combination of the half fairing and the clip-on handlebars seriously restricts the Pantah’s steering lock, which means driveway and parking lot maneuvering is clumsy, requiring back-andforth Y-turns.

The Pantah carries three 10.25-in., drilled-cast-iron Brembo discs, two in the front and one in the rear. Twin Brembo calipers mount to the centeraxle front forks, which have 35mm stanchion tubes, and a single Brembo caliper mounts beneath the swing arm.

The fenders, side panels, rear section and seat base are fiberglass; the gas tank is steel. The seat is secured by three bolts, one on each side and one at the rear. A fiberglass cover can be bolted in place to hide the rear section of the seat or removed to allow room for a passenger or soft luggage. The side panels are each held by two short prongs, which fit into rubber grommets on the frame, and a single bolt. Those bolts screw into ordinary 8mm nuts cast into the fiberglass tailsection, and it’s too easy to dislodge the nuts when replacing the side panels.

For all its sports styling, the Pantah is not especially fast. At the dragstrip, the Pantah logged a best elapsed time of 13.95 sec. with a terminal speed of 94.24 mph. Top speed in the half mile was 108 mph. That’s slightly faster than the BMW R65LS, which turned 13.99 sec. and 93.16 mph in the quarter and reached 101 mph in the half mile, but slower than the 552cc Yamaha V-Twin Vision, which ran 13.09 sec. at 96.87 mph in the quarter. The 550 Fours are even quicker; the Yamaha Seca turned 13.06 sec. and 97.82 mph, the Kawasaki GPz550 did 12.70 sec. and 102.04 mph. In the half mile, the Vision reached 110 mph, the Seca 111 mph and the GPz 116 mph.

Part of the reason lies with the way the Pantah is geared. Our test bike, which we rented from Champion Motorcycles in Costa Mesa, California, was delivered with a 15-tooth countershaft sprocket

and a 36-tooth rear sprocket. With that gearing, the Pantah could theoretically reach 138 mph at its 9050 rpm redline in fifth gear, or 116 mph at redline in fourth gear. In actual fact, there’s no way the Pantah will pull the tall gearing in fourth, let alone fifth.

Because the Pantah is geared so tall, it is difficult to leave a stop quickly, and several downshifts are required for quickly passing traffic on the highway.

With stock gearing, the Pantah turns 3935 rpm at 60 mph. That’s a lot less than the average 550: the Vision turns 5295 rpm at 60, the Seca 4932 rpm and the GPz 4625 rpm.

However, there is no way a Pantah pilot could discern the actual relationship between rpm and road speed, because both of the Nippondenso instruments are wildly optimistic. The tachometer on our test bike read 1000 rpm higher than actual engine speed, and the speedometer showed 60 mph at an actual 54 mph. So, from the rider’s seat, the bike seems to be traveling almost 70 mph and turning about 5000 rpm at an actual 60 mph and

3935 rpm.

To see what effect more realistic gearing would have, we installed a 40-tooth rear sprocket and returned to the dragstrip. The Pantah instantly went half a second quicker, with the best run stopping the clocks at 13.40 sec. and 97.61 mph. Regeared, the Pantah was easy to launch. Instead of bogging off the line, it often spun the rear tire. Pre-start burnouts increased tire traction and led to the quickest elapsed times.

With the lower gearing, the Pantah turned 4379 rpm at an actual 60 mph, and maximum theoretical speed in fifth dropped to 124 mph, a figure still beyond reach. Maximum speed in fourth dropped to an attainable 104 mph.

Top speed in the half mile stayed at 108 mph despite the gearing change, bringing us to the second reason the Pantah is not as quick as other 550s—it doesn’t make as much horsepower.

Nor is it much lighter, weighing 432 lb. with half a tank of gas, compared to the Vision’s 462 lb., the GPz’s 459 lb. and the Seca’s 424 lb. It does feel lighter, because the forward cylinder is almost horizontal, significantly lowering the center of gravity.

Which is a good thing, because with a 57-in. wheelbase, 30.5° of rake and clipon handlebars, it’s already slower steering than any of the Japanese 550s. While all the Japanese models have about the same wheelbase, all also have steeper rake angles (averaging 27°) and wider handlebars, making them more willing to change direction quickly. The Ducati, however, if not having an actual advantage, comes back into the thick of things in S-turns, where the lower center of gravity makes it easier to lift the bike up from a turn in one direction and throw it into a turn in the other direction.

And the Ducati is dead stable under all conditions, unperturbed by fast sweeping turns or bumps or anything else, which, of course, is what the Italians had in mind when designing the chassis and selecting rake and wheelbase.

The Pantah could have steered quicker with less rake angle and a shorter

wheelbase, but stability was chosen over maximum agility. The Pantah does have excellent cornering clearance with tires to match. There is no sidestand, and the first thing to drag on the left side is the centerstand lift tang. Dragging that takes serious lean, and scraping the rearset footpegs while the motorcycle is still on its wheels is impossible. On the right, the exhaust system scrapes first. Cornering clearance is not a problem.

The Pantah has no peer in braking power and control. The Brembo levers themselves are substandard when compared to the levers used on Japanese bikes, being located too far from the handlebar grips and having a square-edged shape which doesn’t conform well to the human hand. A set of dogleg levers would make it easier for normal-sized riders to use the brakes (and clutch). But once past that annoyance, a light pull on the lever produces considerable braking force, and the front wheel can be locked. The excellence comes in how easily the front wheel can be held on the edge of tire-squalling lockup, and in how predictable the brakes are when leaning into a corner. The Pantah’s stopping ability is due to an intelligent choice of leverage ratios and system stiffness. Once the lever is pulled to the point where the pads are against the discs, the lever stops moving. From then on, pressure is the controlling factor. Pull the lever harder and the result is more braking force at the tire, all in a wonderfully linear fashion.

The rear brake requires more pressure for a given amount of braking power than the rear brakes on most other motorcycles. Consequently it can be used hard without fear of locking when heavy front-wheel braking is unloading the rear wheel.

The Pantah stopped from 60 mph in 120 ft., and from 30 mph in 33.5 ft. The stopping distance from 60 mph is noteworthy when compared to the 134, 133 and 128 ft. required by the GPz, Vision and Seca, respectively.

A Pantah pilot will feel more vibration in the handlebars and footpegs than a rider on a rubber-mounted Four, but what vibration the Pantah produces isn’t excessive. At some engine speeds the Pantah is smooth enough that the rearview mirrors (not included in the base price) are crystal clear. At other engine speeds the bars buzz.

Which, combined with the fact that the rider must support his upper torso weight at any legal speed, can cause hands to become numb during a prolonged ride.

The riding position, so well-suited for jaunts at more than 100 mph, is a major

fatigue factor at slower speeds. So, too, is the suspension system, which works well enough at very high speeds but which pounds the rider incessantly at more common speeds, especially over uneven road surfaces or concrete highways. The hard seat could double as a church pew in Puritanical Boston, or maybe as a sawhorse.

The carburetion is flawed as well, with a stumble and hesitation when the throttle is opened at an indicated 5000 rpm, regardless of road speed or other conditions. The condition is most pronounced when the throttle is opened after being held steady at or near 5000 rpm and is caused by excessive leanness at that point. Raising the slide needle one notch helped, but did not eliminate the problem, and we can only wonder how bad it would be if the Pantah did not have accelerator pumps.

At other throttle openings, the Pantah runs rich, briefly belching black puffs of smoke when the throttle is briskly opened and coating the exhaust system insides with soot. The carburetion is rich enough that the chokes don’t have to be used for cold starts, excepting freezing mornings.

Riding the Pantah requires three keys—one for the ignition switch, which is located on the instrument panel, one for the locking gas cap, and one for the fork lock built into the side of the steering head.

The Ducati’s paint and decals are substandard to the least expensive Japanese motorcycles. The horn isn’t much better, emitting a weak squawk instead of the strident warning we’ve come to expect of sporting Italian machines. And the turn signals don’t blink so much as stutter rapidly.

The Ducati Pantah is a very expensive motorcycle, selling for about $5000, and it requires an unusual amount of understanding and patience from its owner. The idea of rider comfort hasn’t come of age at the Ducati factory, and there isn’t much of a distribution system for the bikes in the U.S. The few dealers who do sell Ducatis don’t as a rule stock many parts, and while the owner of a Japanese motorcycle stands a fair chance of buying, say, clutch plates off the shelf, a Ducati owner must wait until the parts are ordered and delivered.

What the Ducati has going for it is its differentness, its birthplace, its acceptance as an object of interest.

The Pantah is fun to ride, rewarding in its own specialised way. But we suspect the only people who will buy one are people whom for whatever reason, really, really want a Pantah. IS

DUCATI

600SL PANTAH

$4949

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1982 -

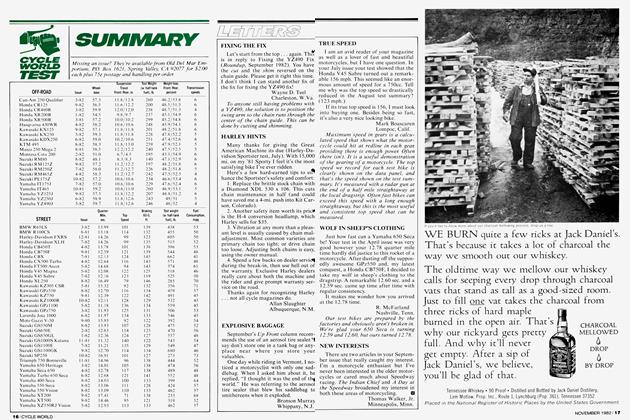

Cycle World Test

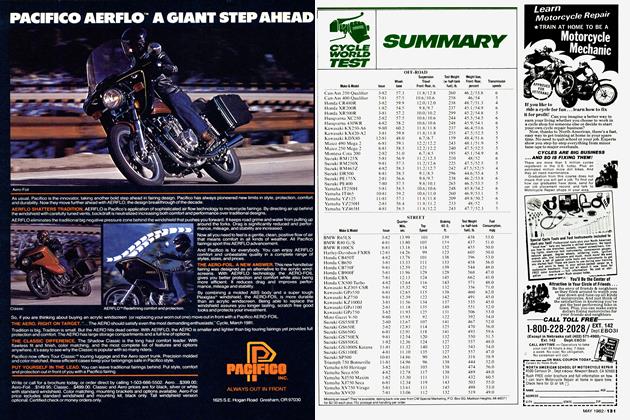

Cycle World TestSummary

November 1982 -

Cycle World Roundup

Cycle World RoundupAutomatically Faster

November 1982 -

Ten Best Bikes of 1982

Ten Best Bikes of 1982Even When They're All Good, Some Are Better.

November 1982 -

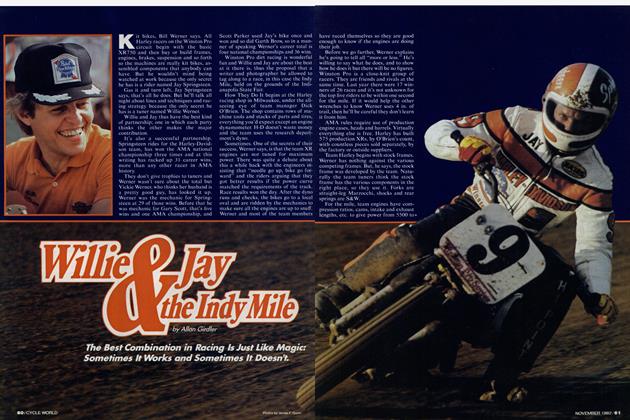

Competition

CompetitionWillie & Jay the Indy Mile

November 1982 By Allan Girdler