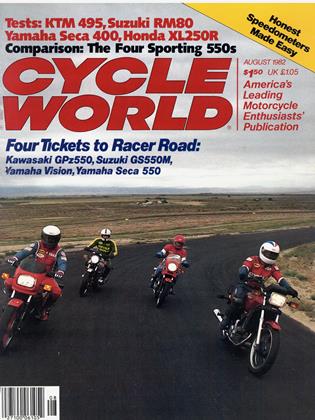

YAMAHA SECA 400

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Lightweight Twin in Yamaha’s New Generation Can’t Be Dismissed as a Beginner’s Bike

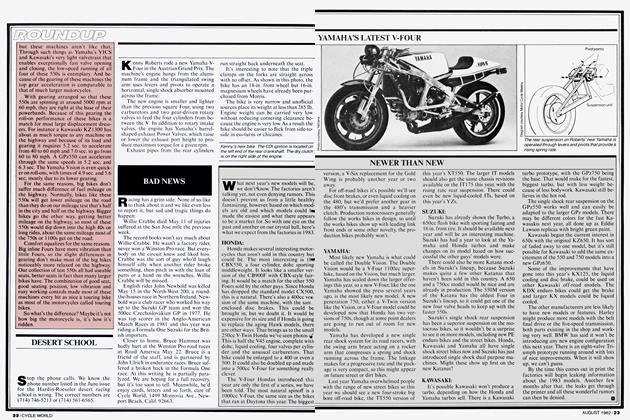

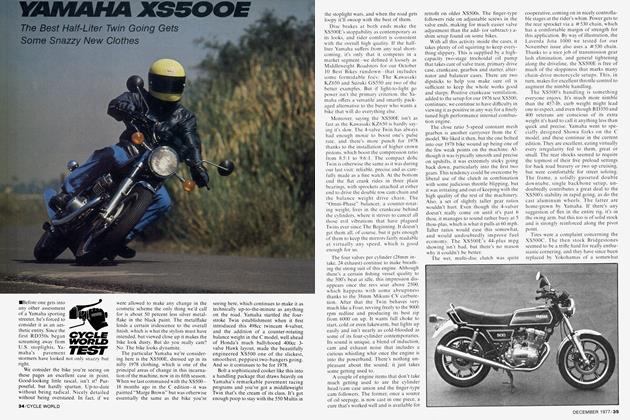

There’s a message in the Yamaha Seca 400, its engine singing at 7000 rpm, the mirrors crystal clear, the seat comfortable, the bars at just the right place for brisk riding. The message is that this is no beginner’s bike.

Myths die hard in motorcycling. One is

that a 400 (or 450) is a beginner’s bike, a motorcycle for first-time buyers, for neophytes, freshmen, kids. That idea is hard to reconcile with the Yamaha Seca 400’s facts: dohc Twin with 42 bhp, gear-driven dynamic engine balancer, YICS, monoshock rear suspension, front disc brake, quartz headlight, over 250 mi. of range on a single tank of gas, and enough power to turn the standing-start quarter mile in 14.03 sec.

Yamaha’s research shows that fewer

than one-third of the riders who buy new bikes in the 400 class are first-time riders. Instead they are* enthusiasts who’ve owned used bikes and are now ready to buy their first new one. With 400s nudging (sometimes breaking) the $2000 barrier, they’re looking for sophistication and features, for technology and performance. Which makes the Seca 400 understandable.

The Seca replaces the aging XS400, which replaced the XS360, but beyond >

approximate size and two cylinders, there’s no connection. The Seca is part of Yamaha’s new generation of motorcycles, and shares with the XJ Fours, the Vision and the Virago a philosophy of innovative approach to traditional goals and problems.

It is a 399cc Twin, with bore and stroke of 69 x 53.4mm and 9.7:1 c.r. The crankshaft runs in plain bearings, the throws staggered 180° apart. In between the throws is a gear driving a counterrotating balancer positioned just ahead of the crank. The generator is mounted on its own auxiliary shaft, behind and above the crankshaft, driven by a link-plate chain off the left end of the crankshaft. Because the generator isn’t on the end of the crankshaft, engine width can be kept to a narrow 14.25 in.

Primary drive is straight-cut gear. The clutch has five friction plates and four steel plates, fewer than most, but those plates are enlarged in diameter to produce needed friction area without increasing engine width. The transmission has six speeds and final drive is roller chain.

The Seca has two valves per cylinder, a 36mm intake valve and a 31mm exhaust valve. Cam timing opens the intake valves 42° BTDC and closes them 60° ABDC. Exhaust valves open 32° BBDC and close 72° ATDC. Intake lift is 8.6mm, exhaust lift 8.3mm.

The cams are driven by a roller chain with a manual tensioner, and operate the valves through buckets. Lash adjustment shims ride on top of the buckets and are interchangeable with Seca 550 shims.

The cylinder head includes YICS (Yamaha Induction Control System) to improve low-rpm economy and performance. A small YICS passageway intersects each intake port just ahead of the intake valve. The passageway is aimed directly into the cylinder when the intake valve is open. The two YICS passageways (one for each cylinder) are linked.

The system works like this: a mixture of fuel and air is drawn into the cylinder by the downward motion of the piston, that mixture passing around the opened intake valve. The air is still rushing through the intake port when the intake valve closes, creating pressure in the port. Some of the pressure escapes through the YICS port and is directed into the other cylinder’s intake port just in time for its intake valve to open. At that point the pressurized mixture streaming in through the YICS port is moving faster than the mixture in the main port, and the faster-moving YICS stream swirls and mixes the fuel charge in the cylinder, making it more homogenous for better burning.

YICS is effective at lower rpm, but

does nothing at high rpm, when the time between intake valve opening decreases.

Ignition is transistor-controlled electronic, the pickups positioned on the left side of the crankshaft. Carburetors are a pair of 34mm Mikuni CVs, and the exhaust system consists of two separate head-pipe/muffler combinations linked by a tube running underneath the engine.

The chassis is just as interesting. The frame backbone is made of stamped steel pieces welded into a box section, supporting the ball-bearing steering head in the front and the top mount of the monoshock in the back. Round tubes with flattened ends are welded to the rear of the backbone, one on each side, and run down in an arc to the swing arm pivot. The rear sub-frame consists of tubes running back from the rear downtubes and up from the swing arm pivot area, making a triangle and supporting the seat and tailsection.

The engine hangs from chromed steel

plates bolted to the frame backbone, with additional engine mounts at the rear, above and below the swing arm pivot.

The swing arm is silver-painted steel. The main arms are box-section, with round tubes running up from a cross brace behind the pivot to the monoshock mount, and more square tubes running down from the monoshock mount to just ahead of the axle.

Wheelbase is 55 in., rake and trail are 26.5 ° and 3.7 in. With half a tank of gas, the Seca 400 weighs 399 lb. The bike has a GVWR (Gross Vehicle Weight Rating) of 880 lb., giving it an unusually-high load capacity, 481 lb.

The Seca’s styling is no surprise, being based on the same theme as the 550 Vision and the 650 Turbo. But in the 400-450cc class, it is distinctive, a conscious effort to make the bike look both racy and futuristic. The gas tank is wide at the front and in the middle, and cut

back where it joins the seat. The side panels continue the flowing lines of the tank and carry them back under the seat to the tail section, which is a miniature, stylized copy of the streamlined tail sections found on works 500cc and 250cc Yamaha road racers a few years ago. The front fender flares out just ahead of the fork sliders, again reminiscent of road racing streamlining. The wheels are cast aluminum in one of Yamaha’s two new spoke styles — sort of four two-sided rectangular boxes linking hub and rim. The quartz-halogen headlight is rectangular, as are the instrument console, the mirrors and the taillight.

The front brake is a 10.5-in. disc with single-piston hydraulic caliper. The front brake master cylinder includes a viewing porthole to check fluid level. The rear brake is a 6.25 in. single-leading-shoe, rod-actuated drum.

It’s how the parts and pieces work that

counts the most, and the Seca 400 delivers. The brakes, for example, are strong. The Seca 400 stops from 60 mph in 133 ft. and from 30 mph in 32 ft. Brake feel is excellent, and the dogleg front brake lever delivers maximum braking power close enough to the grip for easy modulation.

The clutch has a dogleg lever, too, and the cable runs out from its holder at an angle to improve cable routing with the relatively short handlebars. The choke control (actually an enriching circuit) lever is found at the bottom of the left handlebar control pod, at thumb’s reach.

The choke control cable on our test bike was kinked a few inches away from the lever. The kink increased friction between the inner cable and its housing, so the cable housing sometimes moved out of its end holder when the chokes were turned off. When that happened, the inner cable fell out of the lever base and

both the inner cable and the housing had to be pushed back into place.

The turn signal switch is far enough above the choke lever that one doesn’t get in way of the other, and the signals are self-cancelling. The signals can be manually overidden by pushing the switch lever straight down instead of side-toside, but occasionally the switch jams after being manually cancelled. When that happens, it takes jiggling to free the switch. It’s a distraction.

The right handlebar control pod includes an engine kill switch and the electric starter button. The ignition switch/ fork lock is mounted on the upper triple clamp, below the instrument panel. The 85-mph speedometer and the 12,000 rpm tach have square faces and are well-lit at night. In between the tach and speedometer are lights indicating oil level, neutral, high beam and turn signals.

The first rider to take the Seca 400 out at night was amazed at the amount of light the bike threw ahead of it, and for good reason. The quartz-halogen headlight has a 65 watt high beam and 50 watt low beam, far more powerful than the 50/35w average 400/450-class headlight. To put it in perspective, the Seca has the same headlight rating as the Kawasaki GPzl 100.

But if the Seca 400 has a big-bike headlight, it definitely has a little bike horn. For years we’ve wondered why smaller motorcycles come with inadequate horns. The closest manufacturers come to answering the question is to make references to economics. The next question must be, then, how economics can allow a superior, more-expensive headlight but not a horn loud enough to deal with errant drivers of air-conditioned, stereo-equipped automobiles.

The engine characteristics and performance of the Seca are more to our liking. The engine starts quickly after standing overnight, and idles steadily at about 3000 rpm with full choke. It takes a minute or two before the Yamaha can be ridden off, but after that the bike responds well. Once underway, the choke can be turned off almost immediately.

The counterrotating balancer shaft counteracts most of the engine vibration, making the Seca 400 noticeably smooth. There is no strong buzz in the bars or seat or pegs, and the familiar Twin-cylinder mirror blur is missing. This may be the smoothest vertical Twin of any size.

It’s also economical. On the Cycle World mileage test loop, the Seca returned 64 mpg when ridden at mostlylegal speeds. Off the test loop — a mix of highway, city and country roads — the mileage never got below 50 mpg even when the bike was accelerated hard from every stop and cruised at 70 and 80 mph on deserted roads. Even at those speeds, even with quick starts and frequent visits to the 10,000 rpm redline when running >

up through the gears, the Seca had a prereserve range of over 200 mi. At legal speeds, range before reserve almost touches 290 mi., outstanding for any motorcycle. Most bikes in the Seca’s class have ranges of less than 150 mi. under the best conditions and little more than 100 mi. when ridden with vigor.

Smooth, yes. Economical, yes. But loaded with low-rpm, torque, no. This is, after all, a 399cc Twin. Y1CS or no YICS, the engine doesn’t make much power at low rpm. It likes to spin, and brisk acceleration means keeping the engine above 6000 rpm, or, better still, 7000 rpm. In sixth gear, 60 mph is 5500 rpm, and quick passes of slower vehicles demand two downshifts. Even around town we rarely let the Seca’s engine speed drop below 5000, because there’s nothing there.

Kept spinning, the Seca makes reasonable power. It isn’t the fastest thing in its class, delivering an elapsed time of 14.03 sec. and a terminal speed of 90.81 mph at the dragstrip. But while that’s slower than the CB450T Hawk and the GS450S Suzuki, it’s faster than the KZ440. In a half-mile run, the Seca 400 reached an even 100 mph.

The Seca’s long range and big load capacity and willingness to cruise at relatively high speed aren’t the only attributes that make the bike a contender for longer trips or touring. The seat is excellent, wide enough and long enough and soft enough to keep the rider happy long after most 400/450 pilots would be parking for relief. The seating position suited our testers, the relationship between bars and seat and pegs right for sporty riding and lean-into-the-wind highway flying.

The Seca’s forks have no adjustment for preload and don’t have air caps. Rear shock spring preload can be adjusted, but damping and air pressure cannot. As delivered, the Seca’s suspension does a good job of dealing with a range of rider weights, road surfaces and types of riding. It is as good as — maybe better than

— anything in its class.

The advantage of adjustable suspension is that it can be tuned for the rider and purpose at hand, made stiffer for sporty riding and softer for a cush highway ride. Because the Seca lacks this adjustability, it must have suspension somewhere in the middle. The ride is choppy on concrete highway expansion joints.

The short wheelbase and steep rake and light weight make the Seca 400 a quick handler. Direction changes don’t require much input. For the same reasons, the Seca is more affected by crosswinds than larger motorcycles, and the rider must pay close attention to hold a steady course in gusting winds. But that ability to turn quickly is an asset on twisty roads.

The Seca changes direction effortlessly and is easy to ride quickly. It has excellent cornering clearance and is very stable in fast, bumpy sweeping turns after the tires and suspension have warmed up

— during racetrack testing, it took one wobbly lap before the Seca handled well. The rear shock did not overheat and fade, an encouraging sign. The stock tires worked well at the lean angles attainable with the stands installed.

The Seca 400 is a big improvement over the old XS400 and comes with many appealing features, such as long range

and a comfortable seat. It could use more power to keep up with its larger competitors, and may well become a 450 sometime in the future, according to Yamaha representatives. Even as a 400, the Seca is a serious, competent motorcycle worthy of any rider’s attention. 19

YAMAHA SECA 400

$1999