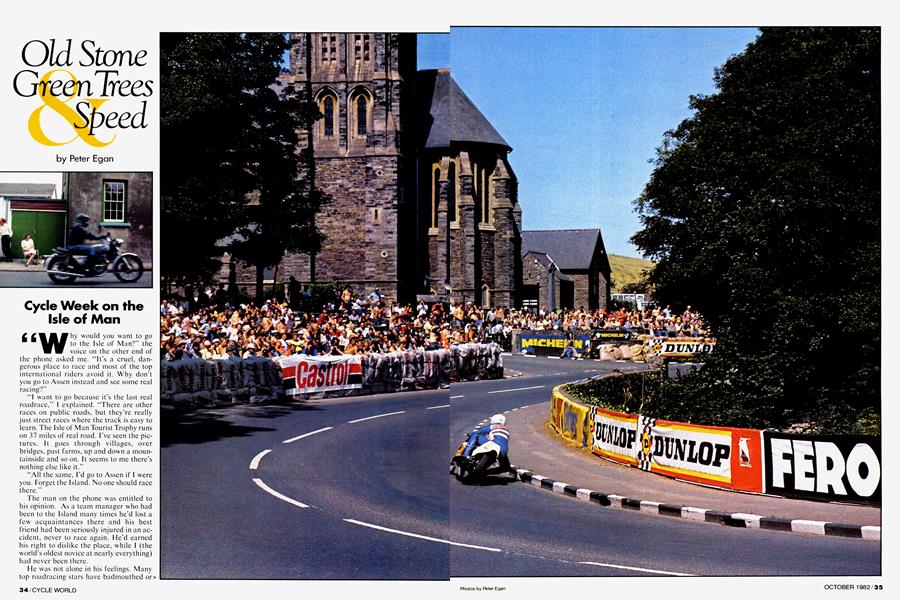

Old Stone Green Trees & Speed

Cycle Week on the Isle of Man

Peter Egan

"Why would you want to go to the Isle of Man?” the voice on the other end of the phone asked me. “It’s a cruel, dangerous place to race and most of the top international riders avoid it. Why don’t you go to Assen instead and see some real racing?”

“I want to go because it’s the last real roadrace,” I explained. “There are other races on public roads, but they’re really just street races where the track is easy to learn. The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy runs on 37 miles of real road. I’ve seen the pictures. It goes through villages, over bridges, past farms, up and down a mountainside and so on. It seems to me there’s nothing else like it.”

“All the same, I’d go to Assen if I were you. Forget the Island. No one should race there.”

The man on the phone was entitled to his opinion. As a team manager who had been to the Island many times he’d lost a few acquaintances there and his best friend had been seriously injured in an accident, never to race again. He’d earned his right to dislike the place, while I (the world’s oldest novice at nearly everything) had never been there.

He was not alone in his feelings. Many top roadracing stars have badmouthed or> boycotted the race for years, so much so that the TT was finally relegated to minor league status. People like Sheene, Roberts, Mamola and Luccinelli didn’t race there now. The best riders at the Isle of Man these days raced because they loved it or because they considered the starting money worth the effort, or both. And then true road racing has always demanded peculiar skills and a different type of concentration than short circuit racing, so many riders have probably continued to come to the Island simply because they are very good at it.

Added to that is the sheer romance of the place. For most of the Twentieth Century the TT has been the world’s supreme motorcycle race. To win at the Isle of Man was to become legend, and every great rider of the past has been required to master the fast, difficult circuit to cement his reputation as a roadracer. Names like Duke, Read, Agostini, Hailwood and dozens of others are inextricably tied to the TT, and the very bumps, corners, bridges and hills of the circuit itself are as famous as the riders. Ballaugh Bridge, Windy Corner, Creg-ny-Baa and Sarah’s Cottage are as well known to TT fans as the name Mike Hailwood. A mental map of the track, with all its strange-sounding Manx place names, is a permanent fixture in the minds of most racing enthusiasts in the British Isles and elsewhere.

The race has been held since 1907, when England refused to allow such craziness on its own public roads and the largely autonomous Manx (they have their own parliament called the Tynwald) offered their lovely island to the Auto Cycle Union for the Big Race. So the TT has been around a few years longer than the Indy 500. Not a bad tradition.

“Thanks anyway,” I told my friend on the phone, “but I think I’ll go to the TT rather than Assen. I’ve been reading about Ballacraine and Cronk-y-Voddy since I was twelve years old. There’s a picture on my wall of Agostini and his MV airborne at Sulby Bridge. At home I have a TT record album with the sound of Mike Hailwood screaming down Bray Hill on the Honda Six. It's a place I’ve wanted to go ever since I gave up shooting frogs with a BB gun, and now, after all these years and at the advanced age of thirty-four I am finally going, bygod, to the Isle of Man.”

There are a lot of ways to get to the Isle of Man, but I naturally took the Easy Motojournalist Route, which involved flying to London, borrowing a GS650G from the nice folks at Heron Suzuki GB Limited, riding halfway across England to Liverpool and taking the Packet Steamship Co. ferry to the Isle of Man. My wife, Barbara, came with me.

We left notoriously sunny LA in a gloomy rain and arrived in famously gloomy London on a hot, cloudless day. A friendly gentleman named Ray Battersby signed over the Suzuki and drew us a detailed labyrinthine map to guide us out of Greater London. And make no mistake, London is Great. We threw our only luggage, a tankbag and some soft saddlebags on the Suzuki and headed northwest.

Ray’s last words as we pulled out of the parking lot were, “Drive on the left!” As it turned out, I had no trouble remembering to drive on the left, but all week I kept

looking the wrong way as 1 stepped off curbs. There are many different types of horns on English cars, and most of the cars have superb brakes.

After looking at Ray’s map 1 suggested to Barb we pay a cab to drive to Liverpool and then follow him with the bike. The map worked fine, however, and after an hour we were free of London and its endless high-speed roundabouts. We avoided the big Motorways and headed toward Liverpool on the more interesting two-lane winding secondary roads.

England isn’t a very dull country to cross on a motorcycle. The land is so condensed in the overlapping layers of its own history that the name on every road sign seems to be famous for something, be it a battle, king, school, bombing raid, sporting event, novel, factory or rock group. Our route took us past Hampton Court, Windsor, Blenheim Castle, Henly, Rugby, Oxford, Stratford-on-Avon, Birmingham and into Liverpool. England is an old country with an animated past and men with something on their minds have been tramping around on its soil for a long time.

We rode into a cool, gray Liverpool late in the afternoon, following signs to the Liverpool Car Ferry with a motorcycle throng that grew larger as we got closer to the docks. We were either on the right road or every motorcyclist in England had been seized with some kind of lemming madness. Policemen on the wharves directed us into an immense holding shed with a glass panelled roof, where guards at the entrance checked the fuel level in our tank and gave us a Tank Inspected decal. You no longer have to empty your tank for the Isle of Man ferry, but the fuel has to be low enough that nothing sloshes out in a rough sea. The boat company doesn’t want a cargo bay full of gas fumes and expensive motorcycles, especially in a country where virtually everyone smokes.

We handed over the tickets we’d ordered in advance (about $38 round trip for two people and a bike) and rode down a steep ramp into the cargo hold. Loading men lined the bikes up on their centerstands, slid them into tight rows and then strapped each row down with rope about the thickness of a fire hose. They pack about 500 bikes into each shipload, which is a lot of chrome, mirrors, fairings and handlebars crammed into a small place.

Up on the passenger deck the ferry boat had the look of a troopship for some kind of motorcycle army. The deck was packed with a crazy mixture of Barbour suits, boots, helmets, racing leathers, touring leathers, and fringed leathers, the predominant color being black with a sprinkling of Kenny Roberts Yellow and Barry Sheene Red. There were hard and soft looking women, bespectacled school teachers carrying pudding bowl helmets, wild rocker types in fringed leather who look like Ted Nugent with more tattoos, mature Germans with BMW patches on full road leathers and vintage men with chestsful of meet pins glittering on their thornproofs. If there was a uniform on the boat, it was black roadracing boots worn over Levis topped off by a Belstaff or leather roadracing jacket and a full-face helmet with a racing theme paint job.

While some elements in American motorcycling take a lot of trouble to select riding gear that makes them look like skiers or snowmobilers, European and English bikers are less apologetic in their choices. They wear first-rate, expensive paraphernalia that leaves no doubt they are Serious Motorcyclists; they like going fast or appearing to go fast and dress the part when they are riding.

Their bikes reflect the same attitude. It costs money to go to the island and stay there for a week, and most people are using a week or more of precious vacation time to be there, so once again you get a committed rather than casual brand of motorcyclist. Big sport bikes and classio restorations predominate, while the fulldress touring bike is all but absent.

The harbor lights of Douglas, the largest city on the Isle of Man, appeared out of the mist just after dark. As we eased into the dock a voice on the PA instructed riders, in three or four languages, to report to their bikes. We went down into the cargo area and picked our way through the mass of bikes to the Suzuki. The same burly guys who tied the bikes down were removing the ropes.

If Federico Fellini ever gets a little farther out and wants to film a truly bizarre spectacle taken from real life, he should bring his camera crew and sound men into the cargo bay of the Isle of Man ferry on a night when approximately 500 motorcycles are being cranked over or kick started all at once, packed together in a steel room about the size of a small gymnasium and lighted by a dim row of 40 watt light bulbs.

The microphones would pick up an earsplitting confusion of shrieking RDs, highrevving unmuffled Fours and the general chest-pounding thunder of Ducati 900s, Norton 850s and 750s, Harleys, Triumphs, BSAs, BMWs and piston slapping British 500 Singles, all of it bouncing off the walls in an incredible rising and falling wail. The camera crews would get footage of several hundred leather-clad people flipping down face shields and punching starter buttons, with others in the mob of bikes heaving up and down on kickstarters like erratic pistons in some kind of insane smoke machine, headlights flaring on to make a blanket of brilliance and flashing chrome at the bottom layer of the smoke cloud. They could catch the bikes launching themselves row by row up the ramp into the dark night, people spinning their tires on the oil slick steel ramp or catching traction and disappearing in half-controlled wheelies.

What no film could capture is the mixed smell of Castrol R, several dozen brands of two-stroke oil and all the other choking thick exhaust fumes, or the instant, furnace-like heat given off by hundreds of motorcycles lighting their engines in a confined space. Also, they’d have to film it through the distorted star-burst pattern of a really scratched yellow face shield, just to get the last effect of profound unreality. You wouldn’t want to witness this scene if you’d been smoking anything funny or you might just go mad and never recover.

Always quick to notice the obvious, I turned back to Barb and shouted, “This is really something!”

I don’t think she could hear me, but I think she knew it was really something.

Our turn came and we slithered up the ramp with a wave of other bikes. We landed on the docks and the white gloves of a row of nearly invisible policemen directed us onto Manx main street, the Douglas Promenade. We were on the Isle of Man.

Douglas is an old seaside resort town with tall, narrow Victorian hotels lining the curve of the bay. The hotels are built wall-to-wall but you can tell one establishment from the other because they are painted different colors. Sidestreets with more hotels and rooming houses climb the steep hillside of the bay to the park and cemetery that border the start/finish line of the TT course. The city is one of those places where you could hide the modern cars, take down the TV antennae and imagine that World War I is still about five years away. There are only two or three modern structures in town and naturally these are made of concrete and are ugly as Hell. The rest of the city is charming.

We checked into a hotel we had picked at random from a travel brochure. It turned out to be a great choice because the staff was a wonderful bunch of people and the pub and restaurant downstairs were both good. The only problems were an occasionally moody water heater and an elevator with a bad memory, so we spent a few evenings scaling great numbers of stairs to reach a cold bath. (Not everyone can claim to have taken a bath “because it’s there.”) We discovered throughout our trip that the reliable heating of water is something of a mystery on the other side of the Atlantic, though the English and Manx are way ahead of the French, who handle hot water the way we do expensive cologne.

Stepping out onto the street, we discovered the great TT Week pastime, and that is strolling up and down the Promenade at night looking at the thousands of motorcycles parked on the street. In one pass you can see an example or two of nearly any motorcycle ever made in every stage of restoration from ratty to concours. For instance, the people staying at our hotel owned—among others—an Ariel Leader, two Heskeths, a Hailwood Replica Ducati, a John Player Norton (not a replica; the ex-Peter Williams bike), a Honda CB 900, a 305 Superhawk and a BSA Gold Star, those being a small contribution to a row that goes on for two miles.

The other great discovery is the people on the street and in the pubs. They formed an impression the first night that lasted all week. The crowd is generally polite, knowledgeable and enthusiastic. Even with all the drinking and pub-crawling at night, there never seems to be any ugliness; none of the usual fistfights, throwing up curbside or shouting clever things at passing women. Even the roughest looking characters never seem to get publicly drunk or nasty. People stand around in groups of friends, pints of Guinness in hand, looking at bikes and talking about racing. I’ve never seen so many people drink so much and have such a good time without anyone getting out of control. They could obviously use some Mean and Stupid lessons from race fans in other parts of the world.

It probably goes back to the cost and committment of getting to the island. In order to get there you have to (a) love motorcycles and (b) be smart enough to read a steamship schedule, both severe obstacles to a large part of the human race. The Isle of Man crowd is a fun collection of people.

In the morning we walked downstairs to the hotel dining room, which proved much easier that walking upstairs from the pub at night, and had a full Manx breakfast, i.e. two eggs, two strips of bacon, two sausages of strange consistency, toast with orange marmalade, juice, half a fried tomato (yes) and a pot of coffee or tea. In England this is known as a full English breakfast and in Ireland it’s a full Irish breakfast.

The Formula One race (for bikes like U.S. Superbikes and/or AMA Formula 1) wasn’t scheduled until 3:00 pm, meaning the circuit was open to traffic all morning. We climbed on the Suzuki and rode up to the start/finish line to take our first lap in the brilliant morning sunshine.

Briefly, the circuit is a 37.7 mile rectangle that looks as though it’s been> shipped parcel post through the US Mail (crushed and dented in spots), running up one side of the island and back down the other. Most of the narrow pavement runs through villages, farms and wooded glens in gently rolling countryside, but at the north end of the island it climbs the side of Mt. Snaefel and then descends in great sweeping stretches all the way to the start/finish line in Douglas.

There are only about a dozen slow corners on the course, so the rest of the circuit can be taken about as fast as memory and icy nerve allow. If you can remember what’s around the next blind corner or over the brow of the next blind hill (and most people can’t) you can ride large sections of the course flat out. If your memory isn’t so good there are a lot of walls, churches, houses, and other fine examples of picturesque stonemasonry waiting to turn you into an ex-motorcyclist.

A first lap around the island is a revelation. Anywhere else it would be a scenic drive through the countryside of a lovely island. But knowing it’s a race track changes your perspective on the road and its corners. The narrowness of the road and the close proximity of walls and other roadside obstacles would make 50 or 60 mph seem plenty fast under normal touring circumstances. Corners, cars and pedestrians are upon you almost before you see them.

At about 70 mph the hedges and walls and overhanging trees begin to blur around the edges of your vision and the road becomes a sort of green and stone and sky blue tunnel. On a street bike anything over 80 mph begins to feel insanely fast, like a wild roller coaster ride, and the forks and shocks begin to hammer and kick the bike around; it bottoms in dips and loses contact with the road over rises, making it hard to pitch the bike into blind corners that unfold in front of you, revealing their peculiarities only after you’ve hit them.

On our first lap my faithful passenger agreed that 80 mph felt quite fast and hinted something a little slower might be more fun (I still have the bruises on my ribs). Racers, of course, go about twice as fast as we did. Really fast guys average about 115 mph around the island, just under 20 min. per lap. Our best lap was about two hours, with a stop for lunch in Ramsey.

Vance Breese and Mike Ross are two American riders who came to the island for the first time this year, bringing a pair of 1300cc Harley-Davidson roadracers with them. Their race bikes were late in arriving on practice week, so they borrowed a couple of big street bikes from some sympathetic Manx enthusiasts. After the first practice lap they pulled into the pit lane in Douglas, took off their helmets and both said, “I hope our bikes don’t arrive in time for the race.” After a few more laps, however, they began to develop some cautious enthusiasm and decided it might not be so bad after all.

“I was unprepared for the speed of the place,” Breese said. “On the map the course looks like it’s all corners, but most of those corners can be taken flat out—if you know where you’re going.”

“You can take one corner on the right line,” Ross added, “but it’ll ruin the line for the next two, so you’ll have to back off to make it, and that can cost valuable seconds. You have to know where you’re going all the time and be thinking ahead.”

The TT course has to be ridden, at any speed, to be appreciated. Coming back into Douglas after that first trip around the circuit, it didn’t feel as though we’d merely done a lap of a race course; it seemed we’d been gone on a week’s vacation and were home at last. One lap is good for more changes of scenery and geography than most people see on a long summer holiday. Thirty-seven miles on the TT circuit is a long trip, and each time you come back into Douglas you feel a little older for the experience. The competitors no doubt feel a lot older.

That first lap also instills a combination of awe and respect for any rider who can set a competitive lap time on the circuit, because a fast lap time is irrefutable proof that the rider has both superb concentration and great courage. A short circuit just doesn’t tell you as much about the people who lap it quickly.

We watched the Formula One race from the grandstand on the start/finish line. Compared with the mass start mayhem of a GP event, the start of the TT is a relatively relaxed affair. The bikes are numbered according to starting order and are released in pairs every 10 sec. They then race for six laps against the clock, rather than directly against one another. After the bikes are gone an attentive quiet spreads over the crowd and everyone listens to the progress reports over the PA system, settling back for the 20 min. wait for the leaders to come blazing through town again.

It didn’t take long for Mick Grant to establish himself as the leader in the F-l race. Three quarters of the way through the first lap he was reported 12 sec. ahead on the clock, and as his Yoshimura Suzuki came howling through Douglas it was announced he’d set a new lap record of 114.93 mph at 19 min. 48 sec.—from a standing start. Joey Dunlop and Ron Haslam were second and third, both on Hondas. Before all the riders streaked into pit row for fuel, Grant had built up a huge 30 sec. lead. But on the last lap he parked his bike at the Hairpin with ignition trouble and Haslam took over the race as Dunlop slowed with handling problems. Haslam took the race, with Dunlop second and New Zealander Dave Hiscock third.

Circle track fans might have a hard time adjusting to a race where the leaders come by every 20 min. or so, then disappear over the hill for another 20. Hearing race reports from distant parts of the track, you sometimes feel a little like a civilian listening to war news from the Falklands. But every 20 min. the war comes through town for a few brief seconds, and when you see the speed of the bikes on the narrow road it gives you pause to realize all those riders have been out there riding like that the entire time you’ve been sipping your warm pint of Okells Bitters and relaxing in the shade. The speed of the bikes (relative to the stationary nature of trees, pubs and your own perch on the wall) is enough to raise the hair on the back of your neck.

In the pub that night everyone was talking about the race, and Mandy the barmaid was explaining to me that a 50/50 mix of Guinness and bitter ale is called a brown split by some and a dark-over-bitter by others. I tried several versions of both and couldn’t make up my mind which was better. Everybody was buying endless rounds for everyone else. I discovered you can never sit in a Manx pub without at least two pints awaiting your attention.

Amid all the racing talk in the pub, two names surfaced over and over again, floating through the acrid smoke and the endless variety of upper and working class British accents. The names were Mike Hailwood and Pat Hennen; Hailwood because he was the absolute smooth master of the circuit, and Hennen, the American, because he rode his heart out with an abandon that is still fixed in the memory of everyone who witnessed it.

“I saw Hennen pass a guy in midair at Ballaugh Bridge and then take the next corner with everything dragging and twitching ... I mean he was scratching, mate. I never saw anything like it. He just bloody well attacked the course .. .” and so on. Hennen was seriously injured on the TT circuit and retired from racing several years ago, but no one who was there seems to have forgotten the smallest detail of his aggressive riding style.

Some pub conversations are easier than others. While it has been said that the Americans and British are two people separated by a common language, it is actually the British themselves who are separated by a common language. There is more stark contrast between the accents > of two Englishmen from neighboring shires than there is between a Cajun alligator hunter from Louisiana and a New York stockbroker. Class and education throw up further barriers in language. While some Britishers speak with the clarity of Prince Charles or John Cleese, others can approach you with such a broad regional dialect that conversation is all but impossible. Just before closing time I had the following chat with a man who seemed to be from England:

“Ha pen the nay thrraa queekum?” he asked me.

“Pardon?”

“Ha pen the nay thrraa queekum?”

“Uh ... oh yeah. Sure.”

“Aye?”

“Aye.”

“Yer a foofa deekin, then?”

“Yeah. You’re probably right. I’m a foofa deekin.”

“Ah. T’is a shame .. .”

I bought the guy a beer before I sank any lower in his estimation. Then I crawled off to bed. I had no idea whether we were discussing piston rings or his wife, so I decided to clear out before I admitted something terrible.

I walked into the hotel elevator and punched the 5th floor button but the elevator didn’t want to go anywhere, so I decided to walk up to my room. I stopped for a smoke break on the 3rd floor landing and the elevator went by with no one in it. By the time I got to my room the cold bath felt good.

The next day was Mad Sunday, when the track is open to the public and the police and their radar guns look the other way. Barb and I joined the stream of speeding bikes for a quick lap. Most of the riders were relatively sane, under the circumstances. The only hairy part was the downhill off the mountain. Every time we came up behind some slow vintage bike, like a smoking Scott Flying Squirrel, I’d check the mirrors and find we were being passed by a Honda 900F going 90 being passed by a Guzzi Le Mans going 100 being overtaken by a Bimota Kawasaki going flat out. This telescoping speed range can make things exciting on Mad Sunday. We passed some kind of accident and later learned a German rider had hit a car and lost his leg.

Much is made of these accidents when the TT is under fire, but when you see the number of people on the island and the amount of driving and riding they do, mishaps are amazingly rare. Americans and their cars seem to do themselves in at a much higher rate on any given holiday weekend in summer, and it would make about as much sense to cancel the Fourth of July as the Tourist Trophy because of the accident rate. This year there were, happily, no racing fatalities. A handful of random crashes, a few serious and most not, but no fatalities. And hundreds of competitors raced thousands of miles.

Races were scheduled every other day for the rest of the week. On the off days everyone rides around to the numerous vintage and owners club rallies held in various villages around the island, or people simply go sightseeing. The Isle of Man is such a pleasant vacation spot it’s worth a week of anyone’s time, even without the races.

The whole island is like a landscape created for a Tolkien novel or a Cat Stevens song. To say the island is quaint does it an injustice; like saying Nastasia Kinski is good looking. There’s more to it than that. The combination of seacoast, fishing villages, farms, forested glens, cottages and villages all fit together to provide a kind of bone deep charm. There is nothing contrived or artificial about the Isle of Man. Brooks tumble, cattle and sheep graze, roses, wisteria and lilacs grow around cottage gates and churchyards, and every time the sun comes out the island glows about fifty colors of green. Throw in a motorcycle race and you’ve got an island that’s first on my list of Places I’m Going to Move When I Get Filthy Rich or Retire.

Norman Brown won the 500cc Senior race (for pure GP bikes) on Monday, riding a Suzuki that was quite a bit faster than ours. A dark horse entrant and pub owner from Ireland, Brown rode a brilliant race, beating South African Jon Ekerold by only 8.6 sec. New Zealander (people come from all over) Dennis Ireland finished third. Mick Grant had led the race for three laps before colliding with a slower rider and crashing without injury. A happy sidelight to the race was that veteran Charlie Williams, after being sidelined with a kinked fuel line during the race, went back out and set a new lap record of 19 min. 40.2 sec. at 115.8 mph. Another fast veteran, Tony Rutter, won the 350 Senior convincingly. Rutter turned in another fine ride on Wednesday, winning the Formula II race on a Ducati 600 Pantah. Dave Roper, one of a small contingent of Yanks racing the island, took 12th in the Formula III race on his borrowed 350 Aermacchi, making some of the nicest thumping noises of the week and looking very smooth and fast.

The last race of the week was the Classic—virtually unrestricted bikes—on Friday. After a gloriously sunny week (unheard of) the island woke up to rain on Friday morning. But it cleared off by noon and by race time the track was dry except for a few treacherous wet patches under the trees. Charlie Williams led most of the race, but retired on the 4th lap. Dennis Ireland took the win, with Jon Ekerold second and Tony Rutter third. The fast guys did well no matter what they rode.

Two of the most interesting entries, at least from an American point of view, were those 1300 Harleys of Breese and Ross. They’d had a tough week with very little practice and the bikes arriving late. A blown motor on Breese’s bike and various mechanical problems had precluded even a full lap of practice on the bikes they were to race. Breese started the race with a hot street motor to replace his blown race engine. Ross retired on the first lap with engine problems and Breese soldiered through with a missing ignition to finish 38th.

“This is really an endurance race,” Breese said later. “Two hundred and twenty-six miles is a long way to go on this road. Next time we’ll be ready for it.”

Breese and Ross had each completed only six laps of practice when the green flag dropped on their race, yet we watched both bikes come thundering through the glen at Barregarrow quicker than they had any right to, bottoming out on the sharp dip and flying off through the corridor of walls and trees. With all they’d been through, just being out there was an accomplishment and finishing was a minor triumph. And they sounded good.

We took the boat back to England on Saturday morning and stayed on deck long enough to see the green island disappear in the ocean haze.

I think my friend on the telephone was wrong. It isn’t that no one should race on the Isle of Man. It’s just that no one should have to race. There is no doubt the circuit is difficult and demanding, so perhaps a rider should race the TT only because he enjoys it and loves the challenge of a true road course, but not because his contract demands it. The Isle of Man is far too nice a place for people to race against their will.

I was partly wrong too, of course. The Isle of Man isn’t important just because it’s the last real road race on earth. It’s important simply because there’s nothing else like it anywhere, and if it disappears there will never be anything like it again.

Try to find another green island in a misty ocean with 37.7 miles of breathtakingly beautiful road and good draught ale where the friendly inhabitants welcome a contest of speed with open arms and the word lawsuit is still regarded with proper disdain. And nowhere else on earth will we find another motorcycle race where the charming ladies of the Women’s Church Guild serve tea and scones on blue and white fine bone china to the race fans sitting on the churchyard wall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAdvice To the Lovelorn

October 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1982 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1982 -

Competition

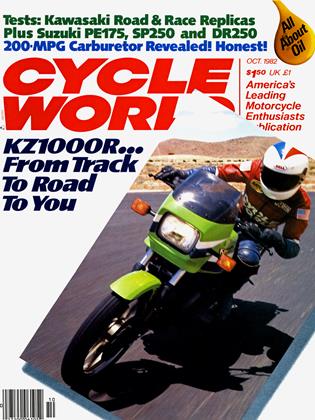

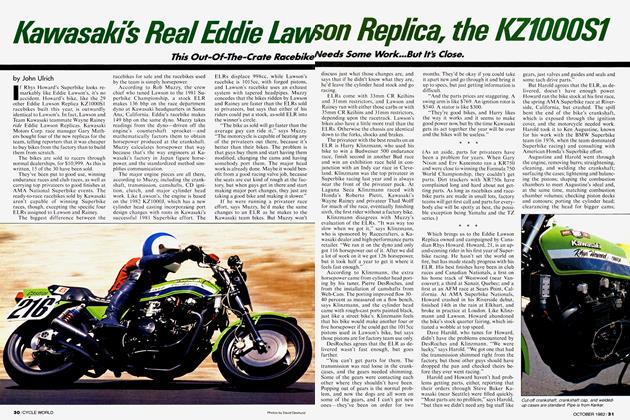

CompetitionKawasaki's Real Eddie Law Son Replica, the Kz1000s1

October 1982 By John Ulrich -

Evaluation

EvaluationRifle Fairing

October 1982 -

Sunday Bide

Sunday BideAlice's Restaurant

October 1982 By William Schiffman