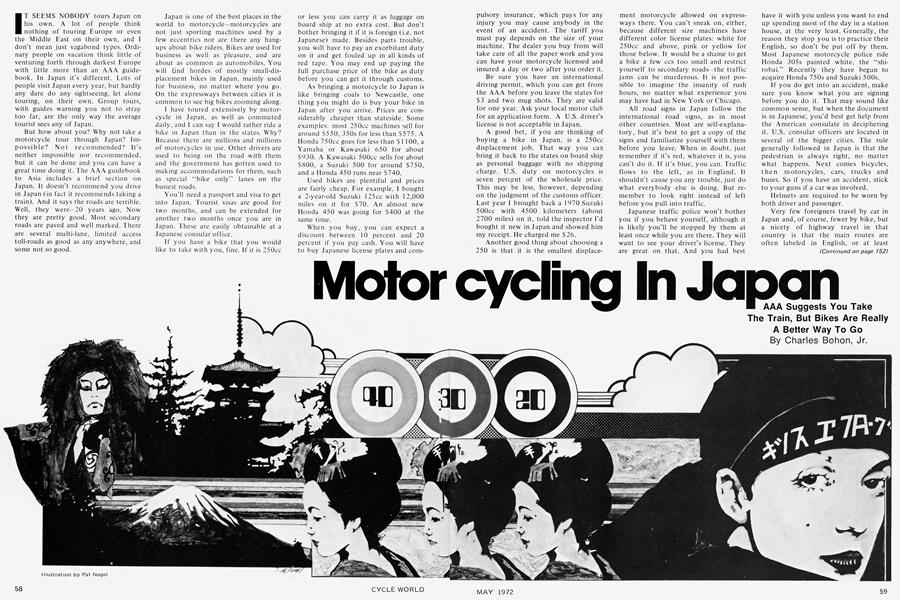

Motor cycling In Japan

IT SEEMS NOBODY tours Japan on his own. A lot of people think nothing of touring Europe or even the Middle East on their own, and I don't mean just vagabond types. Ordinary people on vacation think little of venturing forth through darkest Europe with little more than an AAA guide book. In Japan it's different. Lots of people visit Japan every year, but hardly any dare do any sightseeing, let alone touring, on their own. Group tours, with guides warning you not to stray too far, are the only way the average tourist sees any of Japan.

But how about you? Why not take a motorcycle tour through Japan? Impossible? Not recommended? It's neither impossible nor recommended, but it can be done and you can have a great time doing it. The AAA guidebook to Asia includes a brief section on Japan. It doesn't recommend you drive in Japan (in fact it recommends taking a train). And it says the roads are terrible. Well, they were—20 years ago. Now they are pretty good. Most secondary roads are paved and well marked. There are several multi-lane, limited access toll-roads as good as any anywhere, and some not so good.

Japan is one of the best places in the world to motorcycle —motorcycles are not just sporting machines used by a few eccentrics nor are there any hangups about bike riders. Bikes are used for business as well as pleasure, and are about as common as automobiles. You will find hordes of mostly small-displacement bikes in Japan, mainly used for business, no matter where you go. On the expressways between cities it is common to see big bikes zooming along.

I have toured extensively by motorcycle in Japan, as well as commuted daily, and 1 can say I would rather ride a bike in Japan than in the states. Why? Because there are millions and millions of motorcycles in use. Other drivers are used to being on the road with them and the government has gotten used to making accommodations for them, such as special "bike only" lanes on the busiest roads.

You'll need a passport and visa to get into Japan. Tourist visas are good for two months, and can be extended for another two months once you are in Japan. These are easily obtainable at a Japanese consular office.

If you have a bike that you would like to take with you, fine. If it is 250cc or less you can carry it as luggage on board ship at no extra cost. But don't bother bringing it if it is foreign (i.e. not Japanese) made. Besides parts trouble, you will have to pay an exorbitant duty on it and get fouled up in all kinds of red tape. You may end up paying the full purchase price of the bike as duty before you can get it through customs.

As bringing a motorcycle to Japan is like bringing coals to Newcastle, one thing you might do is buy your bike in Japan after you arrive. Prices are considerably cheaper than stateside. Some examples: most 250cc machines sell for around $550, 350s for less than $575. A Honda 750cc goes for less than $ 1 100, a Yamaha or Kawasaki 650 for about $930. A Kawasaki 500cc sells for about $800, a Suzuki 500 for around $750, and a Honda 450 runs near $740.

Used bikes are plentiful and prices are fairly cheap. For example, I bought a 2-year-old Suzuki 125cc with 12,000 miles on it for $70. An almost new Honda 450 was going for $400 at the same time.

When you buy, you can expect a discount between 10 percent and 20 percent if you pay cash. You will have to buy Japanese license plates and compulsory insurance, which pays for any injury you may cause anybody in the event of an accident. The tariff you must pay depends on the size of your machine. The dealer you buy from will take care of all the paper work and you can have your motorcycle licensed and insured a day or two after you order it.

AAA Suggests You Take The Train, But Bikes Are Really A Better Way To Go

Charles Bohon, Jr.

Be sure you have an international driving permit, which you can get from the AAA before you leave the states for $3 and two mug shots. They are valid for one year. Ask your local motor club for an application form. A U.S. driver's license is not acceptable in Japan.

A good bet, if you are thinking of buying a bike in Japan, is a 250cc displacement job. That way you can bring it back to the states on board ship as personal baggage with no shipping charge. U.S. duty on motorcycles is seven percent of the wholesale price. This may be less, however, depending on the judgment of the customs officer. Last year I brought back a 1970 Suzuki 500cc with 4500 kilometers (about 2700 miles) on it, told the inspector I'd bought it new in Japan and showed him my receipt. He charged me $26.

Another good thing about choosing a 250 is that it is the smallest displacement motorcycle allowed on expressways there. You can't sneak on, either, because different size machines have different color license plates: white for 250cc and above, pink or yellow for those below. It would be a shame to get a bike a few ccs too small and restrict yourself to secondary roads—the traffic jams can be murderous. It is not possible to imagine the insanity of rush hours, no matter what experience you may have had in New York or Chicago.

All road signs in Japan follow the international road signs, as in most other countries. Most are self-explanatory, but it's best to get a copy of the signs and familiarize yourself with them before you leave. When in doubt, just remember if it's red, whatever it is, you can't do it. If it's blue, you can. Traffic flows to the left, as in England. It shouldn't cause you any trouble, just do what everybody else is doing. But remember to look right instead of left before you pull into traffic.

Japanese traffic police won't bother you if you behave yourself, although it is likely you'll be stopped by them at least once while you are there. They will want to see your driver's license. They are great on that. And you had best have it with you unless you want to end up spending most of the day in a station house, at the very least. Generally, the reason they stop you is to practice their English, so don't be put off by them. Most Japanese motorcycle police ride Honda 305s painted white, the "shirobai." Recently they have begun to acquire Honda 750s and Suzuki 500s.

If you do get into an accident, make sure you know what you are signing before you do it. That may sound like common sense, but when the document is in Japanese, you'd best get help from the American consulate in deciphering it. U.S. consular officers are located in several of the bigger cities. The rule generally followed in Japan is that the pedestrian is always right, no matter what happens. Next comes bicycles, then motorcycles, cars, trucks and buses. So if you have an accident, stick to your guns if a car was involved.

Helmets are required to be worn by both driver and passenger.

Very few foreigners travel by car in Japan and, of course, fewer by bike, but a nicety of highway travel in that country is that the main routes are often labeled in English, or at least written in roman letters as well as Japanese so that you can read them. Town names are also often written in roman letters, but this is rarely done in rural areas. Road directions are in Japanese so you had better know where you are going and how to get there.

(Continued on page 152)

Continued from page 59

If you can get a map in both Japanese and English it is better than one written solely in English. That way, if you have to ask someone for directions they can at least show you where you are. If the names are all in roman letters, they may not recognize the spelling or understand your pronunciation, which will probably be wrong.

If those are not available, get one in English and one in Japanese and have someone, perhaps a hotel clerk, copy down your route on the Japanese map after you have gotten it down on the English map. If you get lost thus armed, whoever you ask will know where it is you want to go. Although a surprising number of Japanese know at least some English, the average person does not. It is no time to find out how well somebody reads English when you are lost somewhere out in the boondocks and it’s getting dark. If you do get lost, the best people to ask are high school students because they are usually studying English and enjoy the chance to practice on a real live foreigner.

Gasoline in Japan is as good as you get in the states and gas stations are frequent. You can get pre-mixed gas right from the pump, if you need it. Often you can select the fuel:oil ratio from 10:1 to 50:1.

Gasoline and oil are sold by the liter (1.056 quarts). A liter of regular gas costs around 16 cents. High octane is a few cents more. Mixed gas is 18 cents per liter. Motor oil goes for about $1.12 a liter. Two-cycle oil especially made for motorcycles is never a problem to obtain and costs about $1.15 a liter. Suzuki CCI oil is a common brand sold in bicycle and motorcycle shops and gas stations. Sparkplugs are 70 cents each.

The gas station names will be familiar to you: Shell, Mobil, Caltex. There are also Idemitsu and Nihon Sekiyuu.

Japan is one place in the world where you never have to worry about getting prompt, skilled service for your bike, nor do you ever have to worry about any spare parts you may need. Even in the smallest village, if they haven’t got it they can get it for you in a day or two at most. As the world’s largest producer of motorcycles, Japan ought to provide good motorcycle service, and it does—if it is a Japanese make. If it’s not a domestic job, forget it. No spare parts, no service, no nothing. Off island bikes are extremely rare beasts. The import duties make them prohibitively expensive, and besides, with all the good Japanese machinery around, who needs a Zutmeister 300 or whatever.

Just about any bicycle shop will sell and service motorcycles. It is never necessary to carry spare parts or gas other than what you would normally take on a tour.

Expressways, all toll, connect Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s two largest cities, and Tokyo and the Mt. Fuji area. An elevated expressway circles Tokyo and connects with expressways going to nearby Chiba, Yokohama, and the Enoshima/Kamakura resort area. Other than this, expressways are not common and, like the Chuo Expressway linking Tokyo and Yamanakako, are sometimes only two lanes wide. They are fairly expensive too. The 100 or so kilometers of the Chuo costs about $2. From Tokyo to Osaka, a distance of about 300 miles, costs around $15. The Shuto Expressway circling Tokyo costs 56 cents for a maximum of 28 km. Another 56 cents is charged if you want to go on to Yokohama. There is an excellent six-lane highway, the Daisankeihin, that stretches from the outskirts of Tokyo, near Tamagawa, and runs to Yokohama. It costs 20 cents for a cycle but it is not connected to the Shuto.

Speed limits are usually 50 mph on the expressways and 25 mph inside cities. Of course, all speeds in Japan are in kilometers. Another advantage of getting your bike in Japan is that the speedometer will read in km/h.

A mile equals 1.61 kilometers and a kilometer equals 0.62 mile. Just figure that 100 mph is 160 kph, so 50 mph is 80 kph, and 25 mph is 40 kph. No trouble to convert at all. You’ll be surprised at how quickly you begin to think in kilometers.

Many of the heavily traveled roads have separate lanes for motorcycles and minicars (a minicar is a vehicle with 360cc or less engine displacement). You are supposed to stay in this most left side lane.

Traffic congestion in the cities, especially Tokyo, is very bad. If you plan to do much riding in the city the best times are before 8:30 in the morning and around noon, or else late at night after the bars have closed. Avoid rush hours like the plague and don’t expect drivers to give you a lane all to yourself. They won’t. They will crowd right up next to you and you are expected to stay as close to the edge of the road as possible. Actually this is good in very congested situations, although the roads often have open sewers right at the edge of the pavement, so watch yourself.

Í^ike traffic (motorized and peopleized) s usually able to keep moving when other traffic of the threeand fourwheeled variety is jammed up. Often long lines of a dozen or more bikes will run Indian file along the edge of the road with just enough clearance for the handlebars. Occasionally to get around a bus picking up passengers or a minicar that has tried to negotiate a space hardly wide enough for a Honda Cub, the whole string will hop up onto the sidewalk to pass. It’s not legal, but it’s done.

(Continued on page 154)

Continued from page 153

You can park your motorcycle on the sidewalk, as long as you don’t block the walk completely. You’ll see many bikes parked in this fashion. It’s a lot better than leaving them on the street where they will more than likely get hit by some passing truck squeezing down the most likely narrow street.

Biking is a great way to see the Japanese countryside. Scenery is spectacular, and the weather is temperate. The rainy season comes around the end of May and is usually over by the middle of June. Other than this, there is little rain in the summer. Fall can last through December and the mountain areas are beautiful at this time of year.

A road goes halfway up Mt. Fuji and gives you a spectacular view of the Chichibu mountains, the Kanto plain, the five lakes that encircle the base of Fujisan, and the Japan Alps. If you’ve a mind to, you can hike the rest of the way to the top of the volcano by foot, although recently some university students scaled the peak on trail bikes. Toll for a motorcycle on the Subaru line, one of several routes up the mountain, is a little more than a dollar. It’s best not to attempt going to Mt. Fuji during a national holiday unless you love being trapped in massive crowds.

From Tokyo you can take the Chuo Expressway directly to the base of Fuji. The Chuo ends up where the Subaru starts. The Chuo runs through a beautiful valley between jagged Chinese painting-type mountains with rice paddies and local shrines filling the space between the road and the hills. About halfway along there is a huge lake called Sagamiko set in the mountains. You can take a break here or spend the whole day exploring around it. If you can, wait and see it at sunrise, it is beautiful. Back on the Chuo (ChewOh), the speed limit is usually about 70 kilometers per hour, 40 on the exit ramps. Driving time from Tokyo to the end of the line is about one and a half hours.

If you prefer to wind down the Pacific coast on your way to Fuji you can take the Tomei (Tomay) Expressway from Tokyo and get off at the Gotemba exit. From there drive west on national route 138 through Yamanakako, and up over a huge ridge of hills toward Mt. Fuji. You can take the Subaru line up Fuji just by continuing on past the entrance to the Chuo Expressway.

(Continued on page 156)

Continued from page 154

After ascending Fuji you can return via the Chuo or, if you came by it, return by Tomei. Or, by following national route 139, you can encircle the base of Mt. Fuji and hit the Tomei at Fuji City. This route passes by the five lakes of Mt. Fuji and yields an everchanging view of the sacred mountain. From Fuji City you can return to Tokyo or head southwest to Kyoto, still on the Tomei, so you needn’t fear getting lost.

If you want to take a secondary road to Mt. Fuji, there is national route 20 which pretty much parallels the Chuo expressway and ends up in the same place at Yamanakako. In fact, you will have to travel some 15 or 20 kilometers down NR 20 before you come to the entrance of the Chuo, which is on the edge of Tokyo. Actually, national route 20 originates at Nihonbashi, considered the very center of Tokyo. All roads that lead to Tokyo lead to Nihonbashi and signs showing distances to Tokyo really mean distances to Nihonbashi, which is very close to Ginza.

The choice of roads is yours, but there is very little traffic on the expressway during the week so you’ll have more time to enjoy the scenery.

If you do wish to go on south from Mt. Fuji to the Kyoto area, your best bet is to hike back on to the Tomei and head Nagoyaward at the Fuji or Gotemba interchanges. A couple of hundred klicks and you are in Nagoya. Just outside Nagoya, in Toyota, is the Toyota factory. Toyota is Japan’s biggest automaker.

At Nagoya the Tome becomes the Meishin (Mayshin), but you wouldn’t notice it except for the signs. The two roads are directly connected. The Meishin is older than the Tomei and gas stations are farther between so it is best to top off your tank every time you come to one. The Meishin will take you to Kyoto and Osaka.

Kyoto is a must to visit, with cultural treasures, magnificent temples, shrines and castles you could spend a large part of your life investigating. The city is situated in a valley nestled under massive Mt. Hiei, famous for a sect of Buddhism that has left tranquil temples scattered across the mountain. A toll road leads to the summit where you can get a beautiful view of Kyoto and Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan. The night view is best. There are also wild monkeys scampering about, if you can find them. There are monkey-crossing signs along the roadway, too. From Hiei you can drive down to Biwako before returning to Kyoto.

(Continued on page 158)

Continued from page 156

From Kyoto, a short drive south on route 24 takes you to Nara with its 1200-year-old temples. These include the Daibutsuden, which is the largest wooden building in the world, and houses one of Japan’s great meditating Buddha statues. Nearby Wakakusa mountain has a toll road up it that provides a panoramic view of the Yamato Plain, site of much of Japan’s early history and legend.

From Nara you can return to Kyoto and take the Meishin on into Osaka, site of Expo ’70, or you can take a toll road directly from Nara to Osaka.

South of Osaka there are no more expressways, so you’ll have to do any touring on secondary routes of poor quality amid more countrified citizenry. If you are on a short schedule you could return to Tokyo from Osaka and not really miss too much.

From Tokyo there are several short trips you could make to surrounding areas. Kamakura, once capitol of Japan in feudal days, is only some 50 or 60 kilometers from Tokyo. It is the site of the other large sitting Buddha. Both figures face each other across the distance. From Tokyo you can take the Daisankeihin and connecting routes directly to the Kamakura Enoshima area. Enoshima is a famous island once inhabited by renegade samurai and pirates.

Chiba may also be reached via expressway, but it is an industrial center you may or may not care to visit. However, the eastern coastline of the Boso Penninsula, upon which Chiba is located, has some fine coastline with sand dunes and huge waves sweeping ashore after crossing 8000 miles of ocean with majestic abandon. You will have to navigate backcountry roads to get there, but it is worth it.

I mention toll roads frequently because they are very common in Japan, but for the cycle rider they are no great financial problem. Often the toll for a bike is less than three cents.

A bike tour through Japan is an adventure undertaken by few people. If you are going to the Far East or plan to visit Japan, don’t think you have to leave your bike behind. Your trip will be a thousand times better if you go by motorcycle. Try it.