UP FRONT

DEPARTMENTS

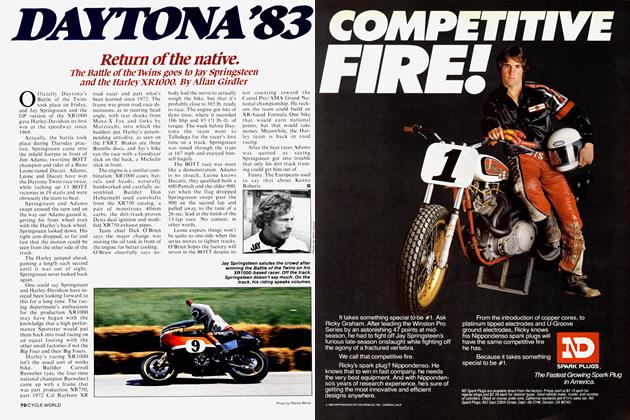

Allan Girdler

IN THEIR DEBT

Because I am on record as having not much respect for the ability of the average driver, and because I was so obviously the guilty party in this incident, I need to set an elaborate stage.

A month or so back I mentioned omens, those signs that maybe you shouldn’t do what you’re about to do. The Sacramento Mile was scheduled for Saturday night, 700 mi. away. Seemed to me it would be a good idea to ride up there, beginning on Friday and finishing Saturday morning, then see the race and ride home Sunday.

On the Thursday before the race I was eating my daily hamburger when in came a mechanic from across the street. He thought whoever was riding the GPzl 100 would like to know the rear tire was holding a big nail. Ha ha, some joke.

No joke. I rode the bike across the street and they had a tube in the tire within the hour. A close call, I thought. I had been especially looking forward to riding the Zl 1, with which 1 have fallen in love, and which I have pulled out of the pool and assigned to me. Out of character, in that my usual choice is Twins or smaller multis, but the sheer power, the clarity of intent, have won me over. My answer to turbocharging, I say to those who ask. The nail, I figured, was merely some trouble taken care of ahead of time.

My plan was to drop by the office on Friday morning, wrap up some minor business and go. I left at 3 p.m., having worked through lunch. Friday afternoon and time to battle across the big city in the worst possible traffic. Rather than wait for the traffic to clear (it never does) I grunted and heaved and zapped and squeaked and fumed to the other side of the metropolitan area.

I pulled off the interstate, ready for

lunch/supper. At the first stoplight I smelled this terrible stench, oil and hot metal. I looked down to make sure it wasn’t my engine.

It was my engine.

I rode into the nearest gas station and looked more closely. Oil was blurping down the front of the cases, the head, onto the pipes. I was blocking traffic to the pumps so without thinking further I banged into gear and lurched across the station, into the bus lane and back into a restaurant driveway.

When I say without thinking I have reference to my having forgotten taking off my goggles.

They fell off the tank bag, into the street.

Into the path of a bus.

Crunch. My goggles, my Climax goggles with prescription lenses by Ellie Taylor, photo gray treatment, the goggles behind which I’d ridden across the desert, through Mexico, to and from work, across Europe and Scandinavia, were now maybe half an inch high. Done for, in other words.

I parked at the restaurant, went in and had a hamburger and a cup of coffee. Then another cup of coffee. I wanted to be calm, relaxed, rational.

Back to the bike, pulse back to normal. Because this is a modern road machine, that is, intricate, I had to take off the saddlebags to get to the harness, so it could come off so I could remove the seat and get the tools. Off came the tank bag so I could remove the tank, after unplugging the outlet hose, the return hose and the electrical connection. No, I didn’t know about the latter two, not until resistance told me the tank was more connected than I'd thought.

Then I learned that if you start the engine with the tank unplugged and off, gas pumps back out the return line. I also learned that rigging the tank so the lines are connected makes it damned difficult to see what’s going on. But one breather hose looked loose, so I walked back to the gas station, bought a clamp, installed it and put back the tank, the lines, the tank bag, the seat, the harness and the saddlebags.

There was still some daylight. I rode off down the nearest surface street, hoping against hope. One mile, no drips. Two miles, a few drops. Three miles, I obviously hadn’t solved the problem.

All I could think to do was limp home. I bought a quart of oil and poured until the sight gauge showed full to the brim. Then I gave the rest to the poor, that is, the kid at the gas station, and headed back down the highway. I didn’t know how fast the oil was pumping out but I hoped to ride 20 miles, check and refill if needed until I got back to the shop. (As it turned out the head gasket had been blown by prolonged over-revving by a car magazine that borrowed the GPz for high speed testing, but I didn’t know that until much later.)

Traffic hadn’t improved. You'd think having the entire population of greater Los Angeles going north when I’d been>

going north would mean empty roads headed south, but no. Still all jammed. My wonderful weekend was turning to, uh, shaving cream.

I was, as they say, one bubble off level.

A week or so before this I’d had one of those days your mother warned you about. It became a day and an evening. When I finally got home I walked in minus helmet and riding suit. My wife looked puzzled. I took the truck, I said, because I was too emotionally upset to be trusted on a bike.

She said she hadn’t known I have that much sense.

Sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t.

Anyway, there I was, distraught, disappointed and going as fast as I dared. My technique in heavy traffic is to run between the fast lane and the next lane, moving with whichever lane is going faster. The idea is that if I use the adjacent car as a shield, nobody from the stopped lane will move over on me. They can’t see us, we all know, but they usually manage to see each other.

The outside lane came to a stop, the inside was cranking along, 40 or 50, me with it when a couple feet ahead a commercial van, no rear window, no rightside mirror, moved to the right edge of his lane.

No malice. No intent. He didn’t cross the white line.

All he did was subtract 12 of the 36 in. I needed for clearance.

There was no time to stop. I jammed down on the bar, jigged right, aiming for the opening, just like in racing when you dive for the hole that isn’t there, diving because there’s no place else to go, concentrating, willing that space to open up because you’ve got to have it . . .

. . . the car next to me moved over. He saw me, the van, read the signs right and gave me the space I needed without putting himself at risk.

I shot through with an inch to spare on each side, safe, sorry and ashamed. I didn’t even stop or slow down because I figured I’d get the lecture I deserved.

The engine pumped out less than a quart in the 100 miles home. I got back to the office and called the airline, got a ticket for the next morning and got to the track in time to watch Springsteen at his best. Elbe Taylor made another pair of goggles and had them here in time for the annual Mexico trip. The head gasket was fixed under warranty: true, the engine had been abused, but the factory authorized the repair because it was they who took the bike back from us to lend to these savagers of good equipment.

So there’s a happy ending after all.

But I don’t think I’ll ever again be quite so smug about the cage drivers in the next lane. E8