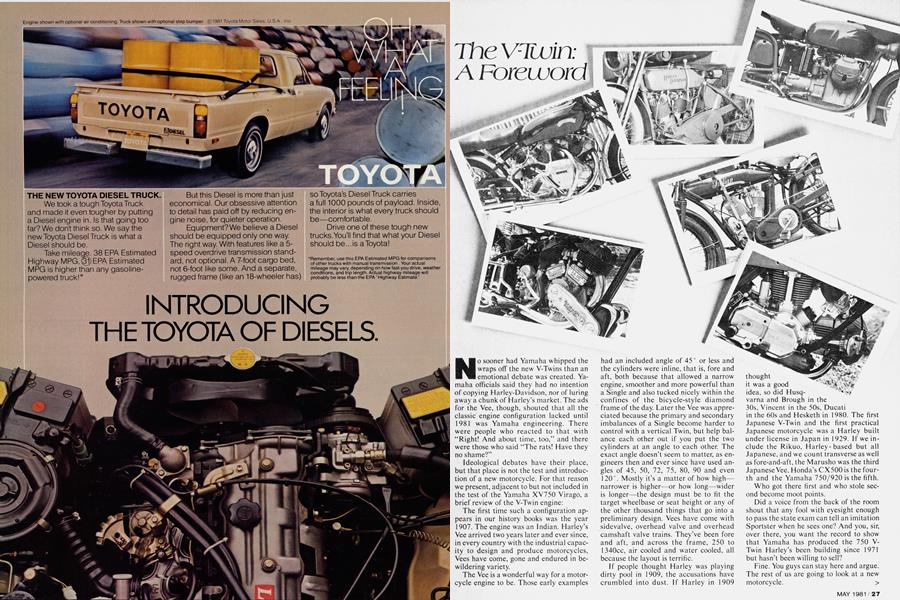

The V-Twin: A Foreword

No sooner had Yamaha whipped the wraps off the new V-Twins than an emotional debate was created. Yamaha officials said they had no intention of copying Harley-Davidson, nor of luring away a chunk of Harley’s market. The ads for the Vee, though, shouted that all the classic engine configuration lacked until 1981 was Yamaha engineering. There were people who reacted to that with “Right! And about time, too,” and there were those who said “The rats! Have they no shame?”

Ideological debates have their place, but that place is not the test and introduction of a new motorcycle. For that reason we present, adjacent to but not included in the test of the Yamaha XV750 Virago, a brief review of the V-Twin engine:

The first time such a configuration appears in our history books was the year 1907. The engine was an Indian. Harley’s Vee arrived two years later and ever since, in every country with the industrial capacity to design and produce motorcycles, Vees have come, gone and endured in bewildering variety.

The Vee is a wonderful way for a motorcycle engine to be. Those early examples had an included angle of 45° or less and the cylinders were inline, that is, fore and aft, both because that allowed a narrow engine, smoother and more powerful than a Single and also tucked nicely within the confines of the bicycle-style diamond frame of the day. Later the Vee was appreciated because the primary and secondary imbalances of a Single become harder to control with a vertical Twin, but help balance each other out if you put the two cylinders at an angle to each other. The exact angle doesn’t seem to matter, as engineers then and ever since have used angles of 45, 50, 72, 75, 80, 90 and even 120°. Mostly it’s a matter of how high— narrower is higher—or how long—wider is longer—the design must be to fit the target wheelbase or seat height or any of the other thousand things that go into a preliminary design. Vees have come with sidevalve, overhead valve and overhead camshaft valve trains. They’ve been fore and aft, and across the frame, 250 to 1340cc, air cooled and water cooled, all because the layout is terrific.

If people thought Harley was playing dirty pool in 1909, the accusations have crumbled into dust. If Harley in 1909 thought it was a good idea, so did Husq varna and Brough in the 30s, Vincent in the 50s, Ducati in the 60s and Hesketh in 1980. The first Japanese V-Twin and the first practical Japanese motorcycle was a Harley built under license in Japan in 1929. If we include the Rikuo, Harley-based but all Japanese, and we count transverse as well as fore-and-aft, the Marusho was the third Japanese Vee, Honda’s CX500 is the fourth and the Yamaha 750/920 is the fifth.

Who got there first and who stole second become moot points.

Did a voice from the back of the room shout that any fool with eyesight enough to pass the state exam can tell an imitation Sportster when he sees one? And you, sir, over there, you want the record to show that Yamaha has produced the 750 VTwin Harley’s been building since 1971 but hasn’t been willing to sell?

Fine. You guys can stay here and argue. The rest of us are going to look at a new motorcycle. >

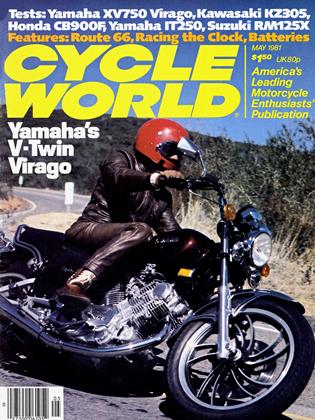

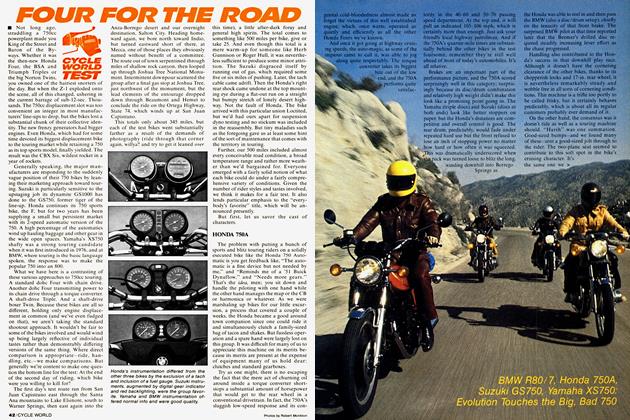

YAMAHA XV750 VIRAGO

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Copycat is an epithet seldom hurled at Yamaha. If such an accusation was made, all the defense would need is to file a bill of particulars: Yamaha persisted with the large vertical Twin long after such engines went out of style. Likewise the two-stroke Twin, ditto the revival of the 500cc road-only Single built in reply to no discernible demand. When all the others scrambled to have 750 Fours, Yamaha replied with a 750 Triple, not long after that engine configuration passed from fashion. The case would never get to the jury, as any judge who knows Munch from Montesa would direct a verdict of not guilty.

Despite what may be said by outside parties, the best guess must be that Yamaha has introduced its V-Twin, in this case the 750 version, because Yamaha wanted to build a V-Twin, which they have done in a manner more Yamaha than anything else built anywhere else.

Beginning with the center of the vee, the engine uses a one-piece crankshaft with roller main bearings and plain connecting rod bearings. Both rods ride sideby-side on the crank’s single throw. Because plain bearings need high oil pressure and rollers prefer lower pressures, there are two oil pumps, with one running at higher psi than the other.

Bore and stroke are 83 x 69.2mm, normally oversquare for big Twins, as it’s calmer to move large pistons quickly than to move smaller pistons over greater distances. The three-ring pistons have nearly flat crowns, providing a compact combustion chamber. Compression ratio is 8.7:1, with two valves per cylinder filling most of the chamber’s roof and the spark plug tucked off to one side.

Now the XV750 becomes different. There are scores of ways the barrels of a VTwin can be laid out. Most common are the, uh, identical Twins; Ducati and Hesketh have the camshaft drives on the same side, the exhausts routed out of the front of each head and the intakes at the back. Due to the demands of space and location, there must be a front barrel and a back barrel, a front head and a rear head. Then there are fraternal twins, like the transverse Honda and Guzzi. These are left and right cylinders, with intakes in the back, exhaust out the front but again, because there are timing chains or pushrods running from the center of the vee, each side is slightly different.

Mirror images, like Harleys and Morinis, have the carbs in the center and the exhausts at the outside of the vee and again, nothing quite swaps.

Yamaha, thanks to a neat twist, has managed to use the same barrel and head, front or rear.

The XV cylinder heads are similar to, but share no parts with, the XT and TT250 Single. Each XV head has one camshaft, driven by Hy-Vo chain. The engine’s included angle is 75° so there’s room for carbs between them—thanks to neat design there, as we’ll see—and the cylinders are offset on the cases, with the rear barrel to the left of the front.

There are two camshaft sprockets on the crank, one on each side of the single throw. Each cylinder has its own cam drive tower, on the outside. So, the front cylinder is fitted with the drive on the right, the intake facing the center and the exhaust in front. The rear cylinder is just like the front, except it goes on a half turn around, with drive on the left, intake facing the vee and exhaust pointing to the back. A mirror image, except that the parts are shared.

Except one. The camshafts are installed from different sides, but of course they must run in the same direction, so the two camshafts are, so to speak mirror images of each other.

The XV has two carbs, 40-mm CV Hitachis and they fit within the vee because they bolt together back to front. The intake tubes turn sharply up and are fed by a tunnel through the large (and different) spine frame. Because the carbs are a unit, their controls are swapped and one cable works both throttles from the center of the unit. The exhaust primary pipes run into a common collector below the swing arm pivot and then to separate mufflers, one per side.

The cylinder heads are designed to be stressed, so the head is one casting. No cam cover. Instead there are small caps for valve clearance adjustment and the cams slide sideways into the head casting. There are rocker arms between cam lobe and valve stem and adjustment is with a selflocking nut and a screw at the rocker tip. Actual adjustment is done with a small alien-head wrench, much better than those cursed little square ends seen on other systems of this type.

Firing order is conventional V-Twin, which may surprise some people.

One advantage of the vee engine is that the imbalance of each cylinder tends to cancel the imbalances of the other. In theory this works best with a 90° vee but the difference in practice has been so small that vees have ranged 45 to 120 °, stopping along the way at 50, 72, 75, and 80, with not much loss of not-shaking, so to speak.

Vees work best when treated like a vertical Twin with a 360° crankshaft. With a vertical Twin, both pistons rise and fall together but when one is on the power stroke the other is on the intake stroke, when one is on compression the other is on exhaust and so forth. This means lots of counterweight to balance the paired pistons but there’s a power stroke every revolution.

Now then. A vee works just like this except that the evenness of the strokes is divided by the included angle of the cylinders. One cylinder fires, then 285 ° later— 360 minus 75 in this case—the other cylinder fires, and 435° after that—360 plus 75—the first cylinder fires again.

This works well. The vee has less imbalance to correct for than the vertical, so it’s smoother for its size and you can make a vee with more displacement than a vertical Twin will tolerate, and there is that distinct loping note to the exhaust.

Most of us think Harley when we hear it. But a Vincent does the same thing and so do Ducati, Guzzi and Honda vees. Because they have wider included angles, the note isn’t quite the same and it’s disguised by different mufflers but it’s there.

This point is mentioned here because there seems to be a belief that Harleys aren’t timed this way. They are. The only exceptions are some Harley XR750s that are built by the factory racing team to run as paired Singles, i.e. the rear firing then the front 45 ° later, then nearly two revolutions of silence then another bu-boom. This is a dirt track trick. Our spies tell us the Harley crew picked it up from some Norton tuners. The theory is that the linked Big Bang gives extra traction. Such engines are known as Twingles. Jay Springsteen uses them on infrequent and unpublicized occasions and they sound like no Harley or Vincent or anything else.

Anyway, the XV is timed like any other vee. What it does differently here is run backwards, in opposition to the direction of the road wheels. We’re told this is to feed vibrations into the frame where they can be damped. But because the XS11 engine also runs backward and uses a conventional frame, and is smooth and has shaft drive like the VX750’s, it's more likely that the reverse rotation allows gear primary drive and one less transmission shaft between the mainshaft and the bevel gear to the driveshaft. The engine’s direction cannot be detected on the road.

The cases split vertically, something of a rarity, and the gearbox has five speeds, using normal road ratios. The oil is carried below the crank in a D****i sort of sump.

Some technical highlights here. This is an ingeniously compact engine. Not counting levers, it’s slightly less than 1 5 in. wide. The front of the forward head is only a few inches in front of the sump, the rear head is just above the rear of the gearbox.

Yamaha has traded lightness for compactness and quiet. The dry engine weighs 189 lb. A dry Honda 750 Four, not the lightest in its class, weighs 195 lb. Twins aren’t always much lighter than Fours.

Nor are they always less complex. The XV750 has two oil pumps. Each of the two cam chains has a slipper on one side and a tensioner on the other. The tensioner is controlled by pressure exerted by a coiled spring with its own housing, the better to be sure chain tension is exactly what it should be and that both chains are balanced. The cam drive gear is actually two gear wheels, one thick and one thin. The thin wheel is spring-loaded. There’s a tiny hole in the hub. The wheels are levered so the teeth are aligned, then the chain is put on and pressure released. Snap, and the chain is under tension. There are wave washers on the bendix drive for the starter to reduce shock and noise there. The little caps for the rocker adjustment have stiffening ribs cast into them. The cam drive cover on the head has a cast-in prong that just clears the bolt that keeps the spocket in place. If that bolt isn’t tight, see, it can’t back out because the prong will block it.

The engine is a stressed portion of the frame, so the cylinders carry weight and are subjected to various loads, in shear, compression and tension, or combinations of all three. The studs from the cases through the barrels and through the heads to the mounting brackets below the backbone are thicker than normal. Plus, because of this stress and the various expansion rates of engine parts working at different temperatures, the head-cylinder surface is machined to be a nearly perfect joint, with lots of contact area. Combustion pressures must also be sealed here so the head gasket is a metallic material wit& a memory; it’s resilient even when the two surfaces are perfectly flush and aren’t exerting pressure on the gasket.

As a result of these and other details, the XV750 engine is strong and small, but not light.

Frame and suspension show equal car®. The frame proper consists of a large and intricate backbone of pressed steel. Many stamped pieces welded together into what’s properly known as a spine frame. No tubes, just one large structure. The steering head fits in one end, the engine hangs from the center, well, just aft of the steering head, and the single shock fits in the other end. Down the center runs a tunnel, ducting air from the filter below the left side of the seat.

The spine curves down to just above the gearbox. The legs of the swing arm join aff of the pivot, for a massive front section that pivots in the back of the cases. There are no frame members proper outboard of the swing arm. Instead what look like castings for the pegs bolt to the engine and run back to carry small tubes that support the seat and fender and various minor parts.

This is nice work and evidence of time spent at the drawing board. The heritagt here must be Vincent. Not because Yamaha used Vincent ideas but because Phil Irving’s Vincent design had a stressed Vee engine with cantilever suspension pivoting on the engine, with an oil tank bolted to the heads and the steering head bolted to the tank. Both were (or have been) done te* best utilize space, to make one component do the work of two or even three. Anil Ducati has a stressed vee as well.

Why? To put the engine in its optimum position. A wide engine, for instance a transverse Four, can't be too low or the cases will drag on corners. A narrow engine, like a Vee Twin, needn’t bother with this worry, so it can be low, for a 1OWG$ center of gravity and a lower seat, tank and so forth.

If there is no separate frame beneath the engine, the engine can be lower still. But unlike the Ducati and Hesketh VTwins, the Yamaha doesn’t have downtubes running from the backbone to tffe crankcase. The Yamaha’s engine provides a greater amount of the frame, which works well with the built-up backbone used on the XV750. The 75° engine angle fits this design perfectly, and the design allows the engine to be as far forward as possible.

And if the engine is forward, and it runs counter to the road wheels and thus can have one fewer shafts in the transmission, then for a given wheelbase the driveshaft can be longer and that means less effect from the shaft on the bike’s rise and fair under power or while coasting. That, by the way, rather than the torque being fed into the rear suspension by the bevel gear driving the gear wheel on the axle, is what causes the old up-down symptom that made shaft drive less than purely sports not long ago. Yamaha shaft drives don't have much of this effect and it’s the long shaft, permitted by the short gearbox, etc., that does it.

Monoshock suspension is now in its sixth year of production, so the introduction of the single horizontal shock for a road-only bike will surprise no one and appear new mostly to those who don’t pay attention to motocross or to grand prix road racing, where all the big guys use variations on the solo shock theme.

What the XV750’s system does, aside from work well, is offer suspension tuning so simple that your kids won’t have to explain it to you. Damping is controlled by a large knob at the edge of the rear fender below the seat center. Next to the knob is a cap covering an air valve. The damping knob gives a choice of six rebound rates. The shock actually has 20 settings, but to widen the remote selection the cables must be moved on the shock body. The variations that came on the bike were sufficient to make that not worth the effort. The rear spring is straight-rate and soft but the air fitting lets the rider adjust the rate. Air pressure is progressive. This allows for suspension settings to match rider weight, payload, and day’s intentions, as in Interstate or mountain madness. The forks have air caps with no damping adjustment, which wasn't missed, and no connection between the two fork legs, which makes tuning the forks as difficult as it is easy to tune the rear suspension.

The 19-in. front wheel and 16-in. rear are cast alloy, in Yamaha’s swirl pattern and carry tubeless tires, Bridgestone Mag Mopus in our bike's case. There’s one front disc and one rear drum, a combination that works in wet and dry and saves unsprung weight. The importance of this model is underscored by the battery. There’s not much room below the seat, what with the suspension living there, and the airbox, so behind the righthand cover lives the longest, highest and thinnest battery we've ever seen. Yes, the Yamaha people said, we needed the shape to match the space so Yuasa engineered a battery for the Vees.

The rest of the XV750 details follow current Yamaha thinking. The XV has a low-oil-level warning light, self-cancelling turn signals, a self-attached security chain and a cut-out switch that kills the engine if it’s put into gear with the sidestand down. It doesn’t have the sidestand-down warning light used on the Seca 750 but then, having the engine die once and remembering why may be a better teacher than the light would be.

Styling borders on Custom. Yamaha was the first to really develop the high bar, stepped seat, tiny tank idea, at first with existing models but since then with bikes like the Maxim, which had frames and such designed to work with the style, which they usually do. The XV750 is done this way. Tank capacity excepted—3.2 gal. isn’t much for a 750—the seat and bars and pegs are at least usable, if not perfect for sports or touring.

Then, also a Yamaha method, there’s the name. The official designation is XV750H, but the name on the side and in the literature is Virago.

Umm. The dictionary says a virago is a woman of great strength and courage, or a loud, overbearing woman. Either way, it’s not the sort of name one expects to find on a motorcycle.

Unless one studies how language works. Apache, for example, is a Navaho word. It means enemy. Hard to imagine why an airplane company would call a new model Enemy. But in that case, by the time airplanes were invented the Navaho’s enemy had become a tribal name, then a synonym for courage and daring and besides, Piper had the habit of naming models after Indian tribes, as in Cherokee, Commanche and so forth. Hence, the Piper Apache.

Bonneville was a French explorer who found a big lake and some dried salt. But when Triumph needed a model name everybody knew Bonneville meant speed, which gave us the Triumph Bonneville.

Same thing for the XV750. Yamaha doubts the power of engine capacity to identify motorcycles in today’s new buyer market. Names, as in Exciter, Seca, Maxim and Venturer, are thought to have more staying power. And a Vee engine needs a Vee name. Vixen? Viper? Virago is easier to say than it is to find in the dictionary. If history repeats, the translation of Toug£ Chick will follow the path of the street fighters next door.

Well. What is the Virago, and what does it all mean? First off, the Virago doesn’t fit some of the ideas traditionally applied to V-Twins. As mentioned, the 750 Twin engine isn’t appreciably lighter than some 750 Fours. Nor it much simpler. Fewer pistons, more timing chains and tensioners. The number of cylinders isn’t the deciding factor here. Flathead Harley and Indian engines were marvels of basicness. The Vincent was one of the most complicated and demanding engines ever built We live in an age of foolproof drivetrains and engines surrounded by miles of wiring and electronic gear. When carburetors leaked, one carb was less trouble than four. Now, though, carbs don’t leak and if the black box goes, it goes with no regard to the number of cylinders it served. Fooked at from this viewpoint, the Yamaha XV750 is no more or less complicated than the Yamaha 750 Seca.

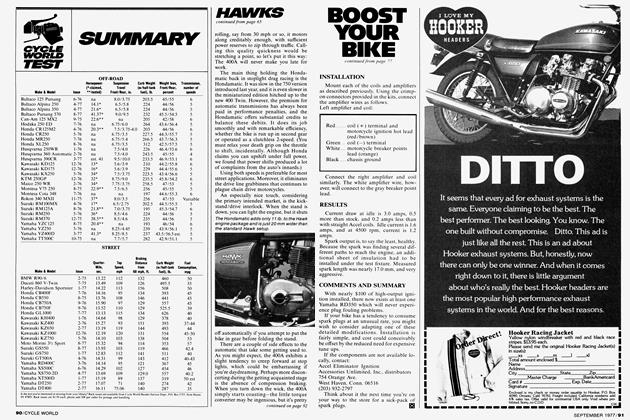

Next, weight. In test trim, with half a tank of fuel, the Virago weighed 498 lb. For reference . . .

Kawasaki KZ750, 492 lb.

Honda CB750F, 538 lb.

Triumph Bonneville (kick start), 425 lb

While the Virago is light for a 750, it isn’t light for a big Twin and it’s closer to other 750s than to other 750 Twins.

Performance. Measured at the drag strip, the Virago again is something of a median 750. It did the standing quarter mile in 13.6 sec. Against that, the KZ750 does 12.26, the 750F does 12.54, the GS750 does 12.33 and the Bonneville does 13.86, so the XV750 is quick for a Twin, not so quick for a 750.

Top gear pull, though, is a little more the way big Twin fanciers would expect. A comparison of 40 to 60 and 60 to 80 mph roll-on figures shows the Virago to be i« mid-pack of the 750s. It’s not quite as fast as the Kawasaki KZ750, but it’s faster than the CB750, despite being geared higher.

Then comes fuel efficiency. The XV clocked 53 mpg around the test loop. The other 750s were; KZ750, 47; CB750F, 48, and GS750, 51.5. The Virago does show a superiority here, but not by much.

Some of these results are linked. Twins usually aren’t high-revving motors, simply because they aren’t in perfect balance and the longer—as a rule—stroke means a lower redline. This applies in part here Only in part, as the Honda CB900F has the same stroke as the XV750 and the Honda Four will happily turn 9500 rpm while the Yamaha’s redline is 7000. What this gets us is lower numerical gearing. At 60 mph, the XV is turning 4013 rpm, compared with 4500 and fractions for the three 750 Fours and 3992 for the Triumph and BMW R80. Gearing for less revs on the road hurts at the drags, in the form of a full second in this case, and helps at the gas station, but not by much.

Another way to look at all these figures is to pretend we’ve been riding around on 750 Twins for 10 years and have just gotten hold of a 750 Four. Look, we’d all say. You can build a Four with no great weight penalty, it will get nearly as many miles from a gallon of gas and wow, is it ever smooth and quick! Turns out the 750 Four is a pretty darn good way to build a motorcycle, which is why so many good ones have been built.

This can be extended into handling behavior. Remember, the V-Twin engine itself is narrow. Taking advantage of this, Yamaha stressed the engine and eliminated the engine cradle and put the engine as low as it could go.

This is something of a compromise. The goal here may have been a low seat. The Virago has that, and because the engine is narrow and so is the tank, the rider’s legs go straight down to the ground, making the seat seem even lower than it is. The low seat brings low pegs, else the rider’s legs would be cramped.

The trade-off here is cornering clearance. The XV drags the right peg and the left peg plus centerstand, and they touch down at lower speeds than the same riders could use on the Fours—we had samples of them along—on the same corners.

This isn’t a problem in itself. Yamaha has also introduced a 750 Four, the Seca. One is in our garage at this writing and will be tested in the June issue. The Seca is a sports bike.

The Virago isn’t. The engine will be used for AMA Winston Pro racing, on the miles and half-miles, but the complete machine isn’t designed for production racing or carving through the mountains on Sunday. The Virago owner who tries to keep up with his pals on Secas will find he's got the wrong bike.

Most of the above sounds more negative than it should be. To appreciate the Virago, it must be judged not as a 750, but as a Yamaha V-Twin.

The Virago sits wonderfully. The low seat and narrow engine and high and narrow bars feel absolutely perfect, completely motorcycle. Your feet are firmly on the ground, your hands are in the position of command.

Flick the bar-mount choke onto full, thumb the starter button and the Vee fires, sounding like ... a V-Twin. Yamaha knows the difference between sound and noise and the XV, like the XS850 Triple and XS650 Twin and 550 Seca, makes good sound without undue noise.

Another offbeat note, as it were, is that Twins usually have narrower rev ranges than Fours. Not less torque at a given speed, necessarily, but while a 750 Four will work from 2000 rpm up to 8500 or 9000 rpm, Vees can be built to pull from 2000 to 7000, or—as in Honda’s CX500, they’ll rev to 9500 and not be worth diddly-squat below 4000.

The XV750 idles with uncanny smoothness. Less shake and throb than any Twin in our experience. It sits ticking away at 1000 rpm so still that you have to check the tach to be sure the engine’s running. Right off idle it has a problem. The engine will pull from 2000 up, but it won't cruise. In town, in any gear above 1st, rolling back on the throttle brings a buck-andstumble. A brief survey of XV750 owners, only a couple because there weren’t that many on the street at the time, tells us ours was not uncommon. We’d guess carbs, something to do with the CV habit of not liking tiny throttle openings, and perhaps the jetting, about which we have some ideas we haven’t tried yet. Until then, the Virago runs best when treated like— gasp!—a two-stroke. Power on, fine, power off, fine, cruising, not good.

What the V-Twin likes best is being used. Once above 3000 on to redline and beyond, it runs well and has that super crisp hammering, from the exhaust and through the bars, of a big Twin working right. Top gear and the open road and it burbles along, spinning a little too fast for a lope, but sounding right. There’s torque and power and if the figures aren’t that impressive, well, the XV feels fast and powerful and who has a stopwatch, anyway?

Redline on the XV is a puzzle. The Honda 900 has the same stroke and a higher limit. Plus, the XV will rev past the 7000 mark quick as a blink, with no drop in power or feeling of strain. Because we don’t lift until we have to, the Virago went through the half-mile clocks at 11 1 mph, although 7000 rpm in top gear is 105 mph. Doesn’t seem to mind, but even though pre-production testing was done with an 8000 rpm limit, and the engine lived, still, we suspect it’s on the side of caution but we can’t advise exceeding it. Usually the factory knows best.

The brakes were a puzzle. The specifications are normal and conventional, i.e. front disc, rear drum. At low speeds, especially when rolling backward out of the garage or parking space, they make the loudest squeal in our experience.

Behavior is normal in town and on the road, but under heavy use, as in the braking tests, front and rear developed what can best be described as a lack of linear effect. Up to a point, they felt right. But beyond that, especially in front, the brakes felt remote. Indirect, as if the rider’s hand was working some control which told some other agency to apply the brake. Not quite flex, not exactly sponginess, more of a vague feeling. Because the riders couldn’t tell exactly where they were on the way to just this side of locking the front wheel, they tended on the side of caution and the stopping distances were longer than we’d expected from the XV750’s weight and brake system.

Clutch travel and gearshift are long, soft and broad and shifting is okay once the rider gets used to having to go all the way up each time. There were no complaints about the controls, except perhaps that having two petcocks gives one the chance to forget and ride on the back cylinder until remembering that the right petcock must be switched onto reserve, too. And the small tank, looks good, might be larger, in case Octopus Oil Co. has placed its stations more than 150 mi. apart.

Yamaha has had time to get the Customs right. The Virago’s wheelbase is long enough, and the bars and seat less extreme enough to make the bike workable for most conditions. The upright riding posture goes unnoticed in town and on the highway for an hour or so, or until a headwind reminds of why sports bikes have low bars and touring bikes have fairings.

Handling is a one-size-fits-all sort of word. The XV won’t keep up with scratchers. That is not to say it doesn’t handle well, because—within design limits—the Virago handles very well.

It steers beautifully. Feels lighter than it is, goes right where it’s pointed. The low center of gravity pays off here. With the settings on the soft end of the scale both ends even out the bumps and pitches. The tires grip right to the lean angle that touches the pegs, and they nibble as you approach that angle, which is as it should be. The Virago tracks on the highway and is nimble in town, thundering ahead here, powering out of corners there. It doesn’t do a good Kenny Roberts impression but it has Uee Marvin right down to the swagger. In a sense the form has limited the function, but hasn’t compromised it.

Don't look for Nortons, Vincents, Harleys, Triumphs and Ducatis in the trade-in section of your local Yamaha store. This isn’t that kind of big Twin.

With the Virago Yamaha has done another good thing. A tradition has been enlarged without infringement. The spiritual forebear of the 750 V-Twin has to be the Yamaha 650 vertical Twin, not because they are alike but because Yamaha engineers saw a basic outline and said we could do that well, which they have, and the Yamaha sales and dealer people said people might like that. And they will.

YAMAHA XV750 VIRAGO

$2998