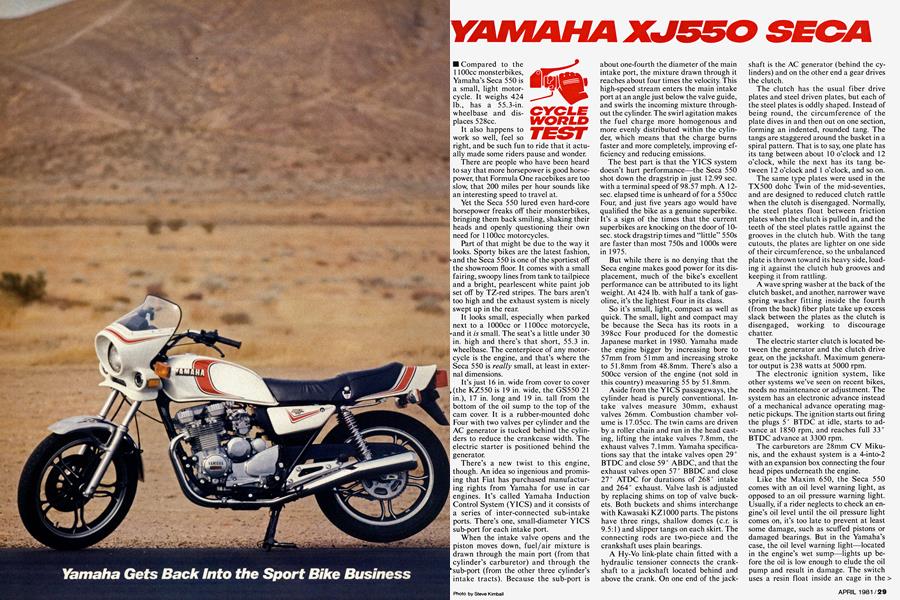

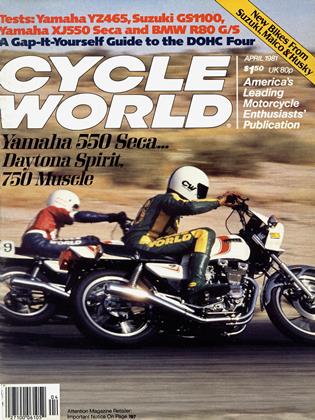

Yamaha Gets Back Into the Sport Bike Business

YAMAHA XJ550 SECA

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Compared to the 1100cc monsterbikes, Yamaha's Seca 550 is a small, light motorcycle. It weighs 424 1b., has a 55.3-in. wheelbase and displaces 528cc.

It also happens to work so well, feel so right, and be such fun to ride that it actually made some riders pause and wonder.

There are people who have been heard to say that more horsepower is good horse power, that Formula One racebikes are too slow, that 200 miles per hour sounds like an interesting speed to travel at.

Yet the Seca 550 lured even hard-core horsepower freaks off their monsterbikes, bringing them back smiling, shaking their heads and openly questioning their own need for 1100cc motorcycles.

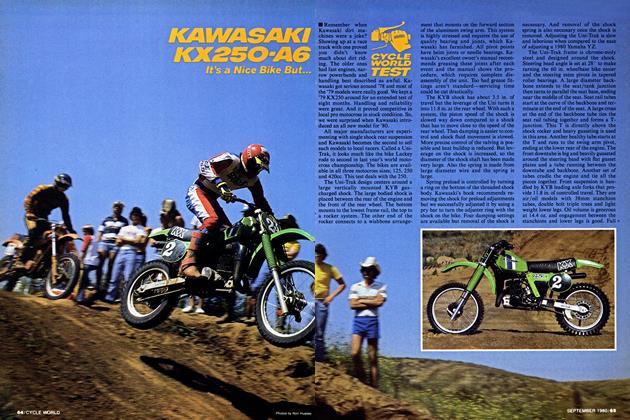

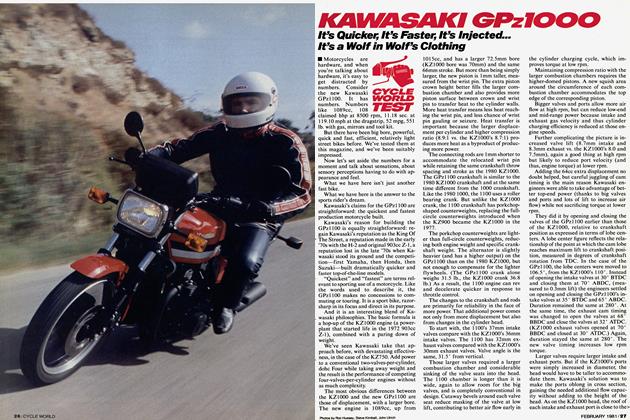

Part of that might be due to the way it looks. Sporty bikes are the latest fashion, and the Seca 550 is one of the sportiest off the showroom floor. It comes with a small fairing, swoopy lines from tank to tailpiece and a bright, pearlescent white paint job set off by TZ-red stripes. The bars aren't too high and the exhaust system is nicely swept up in the rear.

It looks small, especially when parked next to a 1000cc or 1100cc motorcycle, nd it is small. The seat's a little under 30 in. high and there's that short, 55.3 in. wheelbase. The centerpiece of any motor ycle is the engine, and that's where the Seca 550 is really small, at least in exter rial dimensions.

It's just 16 in. wide from cover to cover (the KZ550 is 19 in. wide, the GS550 21 in.), 17 in. long and 19 in. tall from the bottom of the oil sump to the top of the cam cover. It is a rubber-mounted dohc Four with two valves per cylinder and the AC generator is tucked behind the cylin ders to reduce the crankcase width. The electric starter is positioned behind the generator.

There's a new twist to this engine, though. An idea so ingenious and promis ing that Fiat has purchased manufactur ing rights from Yamaha for use in car engines. It's called Yamaha Induction Control System (YICS) and it consists of a series of inter-connected sub-intake ports. There's one, small-diameter YICS sub-port for each intake port.

When the intake valve opens and the piston moves down, fuel/air mixture is drawn through the main port (from that cylinder's carburetor) and through the sub-port (from the other three cylinder's intake tracts). Because the sub-port is about one-fourth the diameter of the main intake port, the mixture drawn through it reaches about four times the velocity. This high-speed stream enters the main intake port at an angle just below the valve guide, and swirls the incoming mixture throughout the cylinder. The swirl agitation makes the fuel charge more homogenous and more evenly distributed within the cylinder, which means that the charge burns faster and more completely, improving efficiency and reducing emissions.

The best part is that the YICS system doesn’t hurt performance—the Seca 550 shot down the dragstrip in just 12.99 sec. with a terminal speed of 98.57 mph. A 12sec. elapsed time is unheard of for a 550cc Four, and just five years ago would have qualified the bike as a genuine superbike. It’s a sign of the times that the current superbikes are knocking on the door of 10sec. stock dragstrip times and “little” 550s are faster than most 750s and 1000s were in 1975.

But while there is no denying that the Seca engine makes good power for its displacement, much of the bike’s excellent performance can be attributed to its light weight. At 424 lb. with half a tank of gasoline, it’s the lightest Four in its class.

So it’s small, light, compact as well as quick. The small, light and compact may be because the Seca has its roots in a 398cc Four produced for the domestic Japanese market in 1980. Yamaha made the engine bigger by increasing bore to 57mm from 51mm and increasing stroke to 51.8mm from 48.8mm. There’s also a 500cc version of the engine (not sold in this country) measuring 55 by 51.8mm.

Aside from the YICS passageways, the cylinder head is purely conventional. Intake valves measure 30mm, exhaust valves 26mm. Combustion chamber volume is 17.05cc. The twin cams are driven by a roller chain and run in the head casting, lifting the intake valves 7.8mm, the exhaust valves 7.1mm. Yamaha specifications say that the intake valves open 29° BTDC and close 59° ABDC, and that the exhaust valves open 57° BBDC and close 27° ATDC for durations of 268° intake and 264° exhaust. Valve lash is adjusted by replacing shims on top of valve buckets. Both buckets and shims interchange with Kawasaki KZ1000 parts. The pistons have three rings, shallow domes (c.r. is 9.5:1) and slipper tangs on each skirt. The connecting rods are two-piece and the crankshaft uses plain bearings.

A Hy-Vo link-plate chain fitted with a hydraulic tensioner connects the crankshaft to a jackshaft located behind and above the crank. On one end of the jackshaft is the AC generator (behind the cylinders) and on the other end a gear drives the clutch.

The clutch has the usual fiber drive plates and steel driven plates, but each of the steel plates is oddly shaped. Instead of being round, the circumference of the plate dives in and then out on one section, forming an indented, rounded tang. The tangs are staggered around the basket in a spiral pattern. That is to say, one plate has its tang between about 10 o’clock and 12 o’clock, while the next has its tang between 12 o’clock and 1 o’clock, and so on.

The same type plates were used in the TX500 dohc Twin of the mid-seventies, and are designed to reduced clutch rattle when the clutch is disengaged. Normally, the steel plates float between friction plates when the clutch is pulled in, and the teeth of the steel plates rattle against the grooves in the clutch hub. With the tang cutouts, the plates are lighter on one side of their circumference, so the unbalanced plate is thrown toward its heavy side, loading it against the clutch hub grooves and keeping it from rattling.

A wave spring washer at the back of the clutch basket, and another, narrower wave spring washer fitting inside the fourth (from the back) fiber plate take up excess slack between the plates as the clutch is disengaged, working to discourage chatter.

The electric starter clutch is located between the generator and the clutch drive gear, on the jackshaft. Maximum generator output is 238 watts at 5000 rpm.

The electronic ignition system, like other systems we’ve seen on recent bikes, needs no maintenance or adjustment. The system has an electronic advance instead of a mechanical advance operating magnetic pickups. The ignition starts out firing the plugs 5° BTDC at idle, starts to advance at 1850 rpm, and reaches full 33° BTDC advance at 3300 rpm.

The carburetors are 28mm CV Mikunis, and the exhaust system is a 4-into-2 with an expansion box connecting the four head pipes underneath the engine.

Like the Maxim 650, the Seca 550 comes with an oil level warning light, as opposed to an oil pressure warning light. Usually, if a rider neglects to check an engine’s oil level until the oil pressure light comes on, it’s too late to prevent at least some damage, such as scuffed pistons or damaged bearings. But in the Yamaha’s case, the oil level warning light—located in the engine’s wet sump—lights up before the oil is low enough to elude the oil pump and result in damage. The switch uses a resin float inside an cage in the sump. The float is doughnut-shaped, and carries a magnet around its center. The doughnut-shaped float fits around a shaft in the center of the float cage, and a reed switch is positioned inside the shaft at a specific height. When oil level drops, the float lines up with the reed switch, tripping the switch and lighting the warning signal.

Of course, the bike comes equipped with the usual self-cancelling Yamaha turn signals, which turn off after the bike has covered a certain distance or the signals have blinked a certain time, whichever is longer. For example, if the bike sits in a left-turn lane for several moments, the system turns off after the bike has made the left turn and gone down the road. But if the rider is traveling down the freeway at high speed and signals for an exit, that distance could be covered in a flash, so the system reverts to the timed operation mode.

Tricker still is the new Yamaha sidestand cutout switch. If the bike is parked on the sidestand and the transmission is in neutral, the engine will start. But if the rider picks up the bike, pulls in the clutch, and shifts into gear without retracting the sidestand, the engine dies. The engine also will not start in gear if the clutch is not

pulled in, or in gear with the sidestand down and the clutch pulled in. The circuit that controls the system gets its information from switches on the sidestand, the shift drum, and the clutch lever.

There’s also a fuel gauge on the Seca 550, and it’s the first accurate one we’ve seen on a test bike. It’s also outrageously responsive. Grab a handful of throttle and you can watch the gauge needle dive toward E as the fuel in the tank sloshes rearward. At steady speeds the needle is stable.

The chassis is straightforward, with liberal use of plastic for sidecovers, airbox, rear fender, etc. in the interests of saving weight.

Yamaha engineers have made extensive use of stress analysis computer programs in designing recent new models. Those studies allow the engineers to determine exactly what stresses a certain part—say, a frame—is subjected to, and how strong it must be to cope with those stresses safely. The result is that the engineers are free to design a part to be just as strong as it must be without over-designing with an excessive safety margin. Which reduces overall weight.

But concern with weight didn’t make

the Yamaha engineers skimp where it re ally counts for a stocker, which is in the braking department. The Seca 550 comes with a single, large (1 1.7-in.) disc with a 1-9/16 in. pad width. The bike stopped in 30 ft. from 30 mph and in 132 ft. from 60 mph, which are good figures.

One of the most important-and most overlooked-factors in brake control is the distance from the grip at which the front brake lever engages serious stopping action. The ideal distance is determined by how long the rider's fingers are. If, foi example, a bike's front brake lever deliv• ers strong braking action so far out froni the grip that only the rider's fingertips reach the lever, the rider will have more trouble controlling the braking action.

Yamaha avoids any problem by provid ing an adjustable lever. A screw (with locking nut) at the inside end of the lever pushes against the master cylinder piston, so moving the screw in or out changes the point at which lever travel turns into mas ter cylinder piston travel, which deter mines when and how hard the brakes come on.

You might think that adjusting th screw couldn't make much difference, bu it does, and anybody owning a Yamaha with the feature should run out to th garage and experiment with the lever fo awhile just to make sure he's got it ad justed right for his hand.

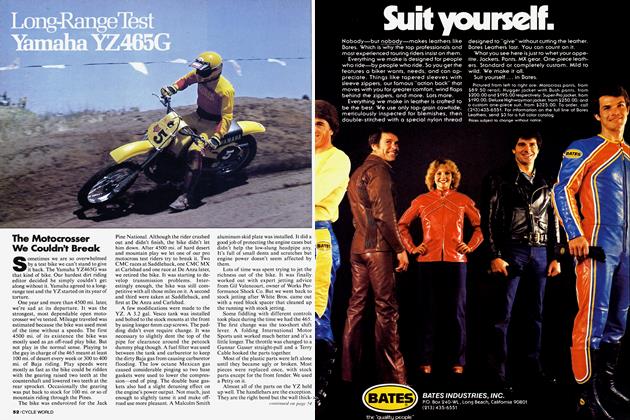

Contributing to the Seca's stopping ability are the tires. Our test bike came with Yokohamas, a 3.00-19 Y990 front and a 110/90-18 Y987 rear. (Secas will also come with Bridgestone L303 front ires and S7 16 rear tires.) Not only are the Yokohamas easy to control when braking, but they work reasonably well for high speed sport riding and don't follow high way rain grooves. A good place to see how a sport bike works overall is the racetrack, and that's where we took our test Seca 50, in the company of another Seca set up for box stock racing by a couple of Ya maha Motor Co., U.S.A. technicians.

The stocker worked better than antici ated. It was easy to ride fast, and didn't ave a ground clearance problem. The ires stuck better than most OEM, and [rastically better than the original tires on he Kawasaki KZ550. In fast, sweeping urns, the tires were the limiting factor in peed, the bike starting to work its way oward the outside in little, controllable teps as the rear tire reached its limits of rip and started sliding. The rider had ex ellent feedback from the tires and never ôund himself sideways without warning, omething known to happen on other ikes.

With the shocks on the lowest preload ;etting, the bike handled fine with a 140lb. rider aboard, except for wallowing ;lightly as the tires slid in one fast turn. The bike dragged the footpegs in tight cor ers and the centerstand tab and sidestand in tighter corners. That was with the rider ianging off per standard box-stock-racing technique.

With a heavier (I 8U lb.), street-oriented rider who doesn't hang off, everything Iragged sooner and more, and the exhaust ;ystem touched briefly in some turns. But on't believe anybody who says that the eca 550 has a ground clearance problem, because there just isn't anything that ouches down in normal street use and Nhat does touch down on the racetrack sn't a problem.

The bike set up for box stock racing was ¶tted with aftermarket tires (a Michelin PZ2 up front and a Pirelli Phantom in the ear, and the tires just didn't slide. But the ike also had stiffer-than stock rear shocks md heavier-than-stock front fork oil. With m 140-lb. rider, the "racebike" wobbled a [ittle in a wide-open, top-gear left-hander. (`hat was probably the result of making he suspension too stiff, the first thing most people do to their bikes and possibly the asiest way to induce wobbling. The sus pension should be set up as compliant and ms soft as possible without encountering continual bottoming and/or problems with ground clearance. With a medium weight rider, the Seca 550 has no clearince problem with the softer, stock sus ension and actually handles better than with suspension mods.

There is no doubt that the Seca 550 is ompetitive in sport riding and on the road race track as far as handling goes. Will it be fast enough to win? With a 12.99 sec~ .t. it would seem so, since that's faster Lhan the 1980 KZ550 went. But we're not pure how fast the sporty, 1981 GPz55O Ka wasaki is, a machine Kawasaki claims has Five more horsepower than the standard KZ550, so we can't make a prediction ibout which one will be the box stock class hampionof 1981.

We do know, however, that the Seca 550 ounds terrific as it flashes by on the ;tràightaway, the exhaust system meeting ill the usual requirements without losing ts appealing, throaty sound. We also know

that the Seca 550 is more comfortable than the Kawasaki 550, with a better seat, and better suspension compliance (mean ing it soaks up those annoying little street bumps and concrete roadway expansion joints). It's also an entirely different-feel ing motorcycle.

The Yamaha is redlined at 10,000 and riding fast demands a lot of rpm. The en gine really comes alive about 6500 rpm, unlike the much torquier Kawasaki, and that may be one reason the Yamaha-in spite of YICS-used more fuel on the Cy cle World mileage test ioop, delivering 56.9 mpg to the 1980 KZ550's 63 mpg.

The high-revving, silky-smoothness of the Yamaha may have something to do with the rider's perception of being on a sporty bike. The feel, the air, the aura of the machine is sporty, from that wailing,

quick-revving engine to the small fairing mounted on the front end. No matter that tucking in is complicated by windshield distortion, or that the fairing directs the windblast right at the helmet faceshield on medium-height riders. No matter that the bars aren't perfectly flat-they actu ally work pretty well on street and track.

This bike's reason for being, its effect on its riders is purely, simply, fun in the con text of sport riding.

For anybody who considers himself (or herself) a sport rider, who likes the semi cafe look, who doesn't want a Monsterbike but wants, well. . . fun. . . the Seca 550 is waiting. Around here, though, the test bike didn't wait for lon2.

Somebody was alwa's ready to ride it away.

YAMAHA XJ550 SECA

$2529