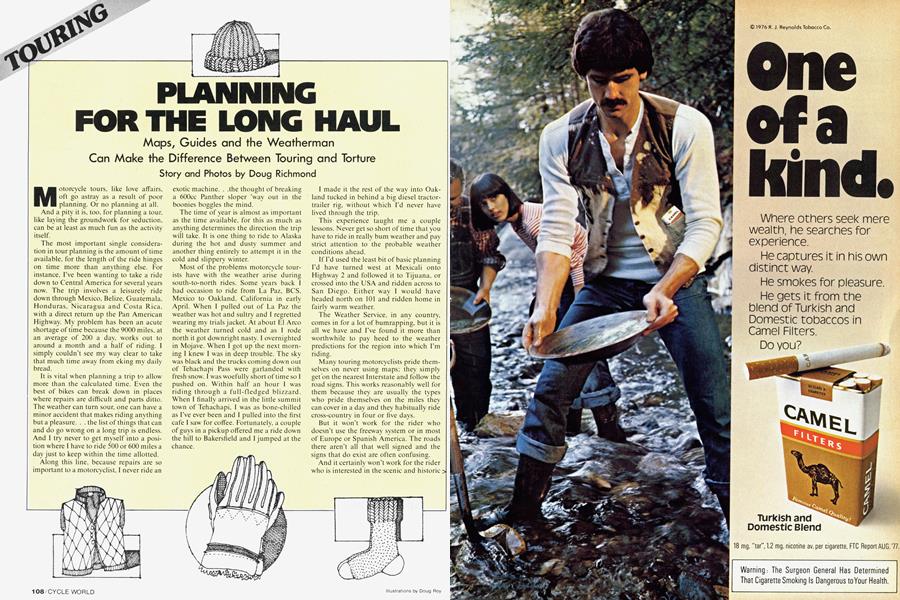

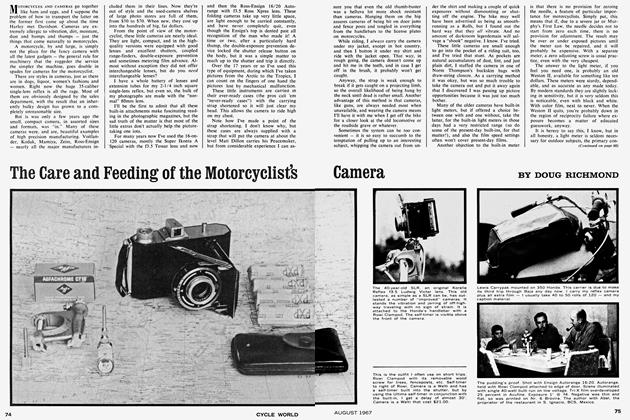

PLANNING FOR THE LONG HAUL

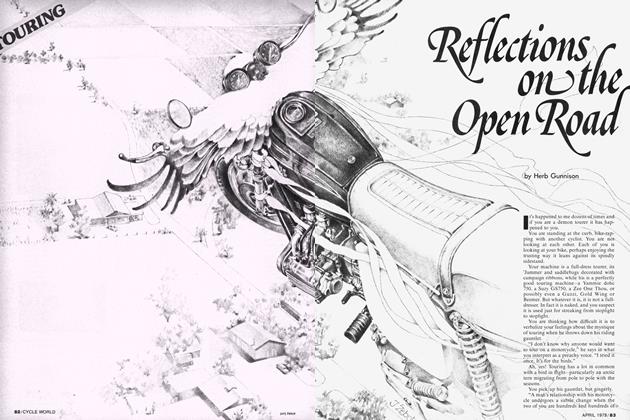

TOURING

Maps, Guides and the Weatherman Can Make the Difference Between Touring and Torture

Doug Richmond

Motorcycle tours, like love affairs, oft go astray as a result of poor planning. Or no planning at all.

And a pity it is, too, for planning a tour, like laying the groundwork for seduction, can be at least as much fun as the activity itself.

The most important single consideration in tour planning is the amount of time available, for the length of the ride hinges on time more than anything else. For instance, I've been wanting to take a ride down to Central America for several years now. The trip involves a leisurely ride down through Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, with a direct return up the Pan American Highway. My problem has been an acute shortage of time because the 9000 miles, at an average of 200 a day, works out to around a month and a half of riding. I simply couldn't see my way clear to take that much time away from eking my daily bread.

It is vital when planning a trip to allow more than the calculated time. Even the best of bikes can break down in places where repairs are difficult and parts ditto. The weather can turn sour, one can have a minor accident that makes riding anything but a pleasure. . . the list of things that can and do go wrong on a long trip is endless. And I try never to get myself into a position where I have to ride 500 or 600 miles a day just to keep within the time allotted.

Along this line, because repairs are so important to a motorcyclist, I never ride an exotic machine. . .the thought of breaking a 600cc Panther sloper 'way out in the boonies boggles the mind.

The time of year is almost as important as the time available, for this as much as anything determines the direction the trip will take. It is one thing to ride to Alaska during the hot and dusty summer and another thing entirely to attempt it in the cold and slippery winter.

Most of the problems motorcycle tourists have with the weather arise during south-to-north rides. Some years back I had occasion to ride from La Paz, BCS, Mexico to Oakland, California in early April. When I pulled out of La Paz the weather was hot and sultry and I regretted wearing my trials jacket. At about El Arco the weather turned cold and as I rode north it got downright nasty. I overnighted in Mojave. When I got up the next morning I knew I was in deep trouble. The sky was black and the trucks coming down out of Tehachapi Pass were garlanded with fresh snow. I was woefully short of time so I pushed on. Within half an hour I was riding through a full-fledged blizzard. When I finally arrived in the little summit town of Tehachapi, I was as bone-chilled as I've ever been and I pulled into the first cafe I saw for coffee. Fortunately, a couple of guys in a pickup offered me a ride down the hill to Bakersfield and I jumped at the chance. I made it the rest of the way into Oakland tucked in behind a big diesel tractortrailer rig, without which I'd never have lived through the trip.

This experience taught me a couple lessons. Never get so short of time that you have to ride in really bum weather and pay strict attention to the probable weather conditions ahead.

If I'd used the least bit of basic planning I'd have turned west at Mexicali onto Highway 2 and followed it to Tijuana, or crossed into the USA and ridden across to San Diego. Either way I would have headed north on 101 and ridden home in fairly warm weather.

The Weather Service, in any country, comes in for a lot of bumrapping. but it is all we have and I've found it more than worthwhile to pay heed to the weather predictions for the region into which I'm riding.

Many touring motorcyclists pride themselves on never using maps; they simply get on the nearest Interstate and follow the road signs. This works reasonably well for them because they are usually the types who pride themselves on the miles they can cover in a day and they habitually ride cross-country in four or five days.

But it won't work for the rider who doesn't use the freeway system or in most of Europe or Spanish America. The roads there aren't all that well signed and the signs that do exist are often confusing.

And it certainly won't work for the rider who is interested in the scenic and historic > out-of-the-way spots, the type to whom motorcycle touring is simply the best sightseeing system yet devised. For these riders, maps—good maps—are a must.

When we first begin to delve into the map situation we are immediately struck by the huge number of maps available for virtually any part of the world. Unfortunately, most of 'em aren't worth the paper they're printed on.

Any road map can be counted on to show the larger cities; I've never seen a map of Spain that didn't show Madrid and Barcelona or a Mexican road map that didn't show Guadalajara and Mexico City. The problem arises when you are interested in Campaspero, Spain or Diabaig, Scotland. My current practice is to get as many maps as I can find and compare them as regards fine detail. . .the finer the detail shown, the better the map.

Almost all maps use fine print for the smaller and more obscure locations, print so fine that I often can't read it at all after I've been in the saddle a while, so I carry a little illuminated magnifying glass called a Magna Lite' that I bought in a stationery store. I've since seen them sold in camera shops and book stores also. In a pinch it will double in brass as a low-power flashlight but it really isn't very good for that purpose. With it I've never seen map detail I couldn't make out.

Most road maps are far and away too big for motorcycle use, because they were primarily intended for use by automobile drivers, but there are several books of maps available that are quite compact. Unfortunately, I've never found one for the Americas. Rand McNally and others put out books of maps of North America but all I have seen are essentially bound volumes of gas station maps, entirely too bulky for cycle use. The most readily available and practical maps of the Americas are of the gas-station type, the kind that used to be free for the asking. To cut down on bulk and to make them easier to handle on windy days I often cut them up into strip maps. And I spray them with clear acrylic varnish (Krylon 1303A) to make them water-resistant and to increase their overall durability.

The best motorcycle maps of Europe I've found to date are contained in the Rand McNally Road Atlas of Europe. This atlas is only 8'/2 x 11 inches and contains over 100 pages . . . about the size of this magazine. Bound in paperback and printed on quite good stock, this atlas is durable and has a comprehensive index. There are a number of other road atlases available in bookstores and newsstands throughout Europe, but I've yet to locate one that is any more convenient to use. The Rand McNally Atlas has the additional advantage of being printed in En-, glish. As it is not too available in Europe I suggest you buy your copy in the United States if a continental tour is your bag.

Unfortunately, this Atlas lacks elevation figures, which most North American road maps have. Elevation can be vital to a motorcyclist because, as a general rule, the higher the altitude the colder the weather. A motorcyclist using maps lacking elevation figures and travelling through Spain might be bitterly surprised to discover that Madrid in winter is colder and more miserable than New York City.

Although there are a few riders who are solely interested in unwinding as much pavement a day as possible, most of us are interested in the history, people and amenities of the areas in which we ride. And the way to find out about them is by reading every guidebook we can get our hands on. The difficulty here is picking the guidebook or books that give us the information we want.

Guidebooks come in all sorts of specialized versions. There are shoppers guidebooks that tell milady how to spend her (old man's) money. There are affluent guidebooks that devote lots of space to tipping and the sort of hotels where a double with bath will set you back a mere $72.64 a night. There are even guidebooks for women, although for the life of me and the lady who often travels with me, we can see no reason why women need different information than men. And there are restaurant guidebooks that, except for the excellent Michelin guides, are the next thing to useless.

What we motorcyclists want is a guidebook that gives us something of the country's facilities and terrain, plus a listing of a few of the more economical hotels. We need to know about a few of the legal problems a traveller is likely to encounter. . .border crossings are much less of a problem in Europe than in Spanish America. And cheap hotels are, as a rule, a great deal more amenable to parking bikes in the lobby than are deluxe establishments. This rule of thumb, by the way, applies to every country I've visited, 17 to date.

Far and away the best guidebooks I've found so far are the books put out by Arthur Frommer for the budget-conscious traveller. Typical titles are Mexico on $10 a Day and Spain and Morocco on $10 and $15 a Day. I won't attempt to list them all because new titles are constantly being added, and the older books undergo a more or less continuous revision. Frommer books are sold at bookstores and the better class of newsstand in Canada, the United States, Mexico and the United Kingdom. They are also sold in other countries, but are liable to be hard to locate—I spent the better part of two days in Barcelona one time looking for a copy of Spain to replace the one I left in my hotel room.

The Council on International Education Exchange (CIEE) publishes very compact guidebooks that contain practical infor-> mation on visas, money and so on. I've used their Student Guide to Latin America and Let's Go: Europe with considerable satisfaction. Available at bookstores.

In the British Isles I've used Nicholson's Guide to Great Britain and was very favorably impressed by its accuracy.

One of the very best places to buy European guidebooks is in the many bookstores and newsstands of London, which makes it handy for Americans because so many of us go to Europe by charter flight to London.

But don't feel limited by my remarks. Seek out for yourself every bit of written information on the region in which you're interested. Haunt the local libraries. Don't neglect books that are long out-of-print, either. Even technical journals often have interesting and practical articles for the traveller if you can wade through their generally-turgid prose.

Note that I've not mentioned the National Geographic magazine—it's deliberate. The reason is that the Geographic habitually looks at the world through rosecolored glasses, and a persistent reading of the Geographic will give a very misleading picture of an area. I've been in places that were later covered in Geographic features and didn't even recognize them. For example, the Geographic did an article on Belize (neé British Honduras) and there was not a single photograph of a black person. If you've been there you know it was quite a trick to do the illustrations for an entire article and not show any black people. (But they did run the obligatory shot of the topless Indian lady.)

For my money, a passport is a necessity for anyone who travels outside his own country, even though the country in which he is travelling doesn't require it. Canada and Mexico are two examples of this, but I have found that having a valid passport eliminates a lot of cross-examination and downright hassling at border crossings with both Canada and Mexico.

A note of caution regarding Mexico: If you are entering the Republic from Central America you can't count on getting your tourist permit at the border as we do going from these United States into Mexico. Better play it safe and get your tourist permit from the Mexican Consul in one of the Central American countries rather than take a chance and wind up riding back a hundred miles or so because you didn't have it!

International Driving License: I've never found the need for one in the Americas, but if you're going to tour Europe it is best to have it. Get yours at the nearest office of the American Automobile Association.

Lots of cycle tourists camp out on their journeys. I don't ifl can possibly avoid it.

To begin with, it takes lots of time to camp out. even under ideal conditions. Setting up and breaking camp, cooking, washing-up are not only time-consuming but actually very tiring in themselves after a long day on the handlebars. I prefer to check into a small motel or hotel early in the evening in a little town where I can park the bike well away from the street and casual thieves, peel off the riding gear, take a leisurely shower, and then go for a stroll around town to get the kinks out of my legs, after which I have a few belts and the best meal available, preferably with wine and candles and all the trimmings.

Obviously this is a personal view. The touring rider who does 300 miles a day and stays in motels is simply a different type tourer than the rider who goes coast-tocoast non-stop, and a different type than the rider who does 200 miles a day from campsite to campsite. Lots of people like to camp. With a little practice they manage to get tent and bedroll and stove safely loaded on the bike. The only planning note needed here is a recommendation that when the camping biker shops for maps, he also looks for guidebooks with campsites, state parks and the like.

Overnighting is where the advantages of reading up on a region beforehand pays off. A few years ago, through a singular lack of foresight, I managed to miss the ferry from Dover. I regard Dover as one of the Queen's less attractive towns, so I got out my Nicholson's Guide and started prospecting for pleasant nearby places to put up for the night and came up with a place nobody ever heard of, Broadstairs. Although Broadstairs really isn't all that near to Dover, I'd only ridden down from London that day so I got back aboard the Royal Enfield and headed up the narrow country roads. Turned out to be as interesting a place as advertised. I was fortunate enough to find a pub on the waterfront where for 2 I could get bed and breakfast and a dry place for the bike in the shed out back. The locals were extremely friendly, although a mite hard to understand, and I .had a fine time until the Guv'nor called, "Time, gents. Drink up!" In fact, I also contrived to miss several other ferries, but counted it as time well spent.

I've saved finances to the last because no two riders take the same route with money. The way I do it, I allow $25 á day in Canada and the United States, $20 U.S. in the U.K. and Northern Europe, and $15 U.S. in Latin America and Southern Europe. Plus a cushion of at least 50 percent for emergencies. I carry Visa and Master Charge credit cards.

And I have yet to spend my daily allotment.