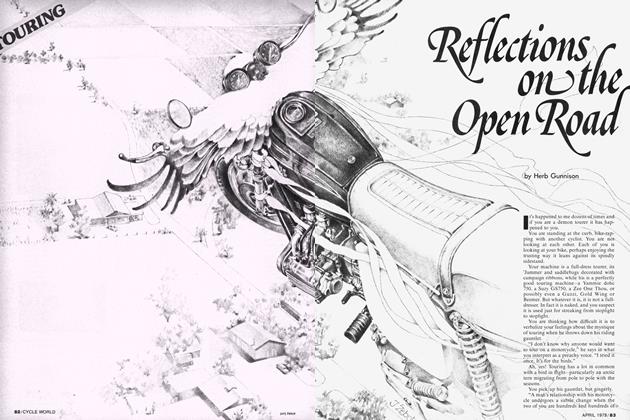

RIGGING FOR THE ROAD

TOURING

What One Experienced Rider Has With Him When The Inevitable Happens

Doug Richmond

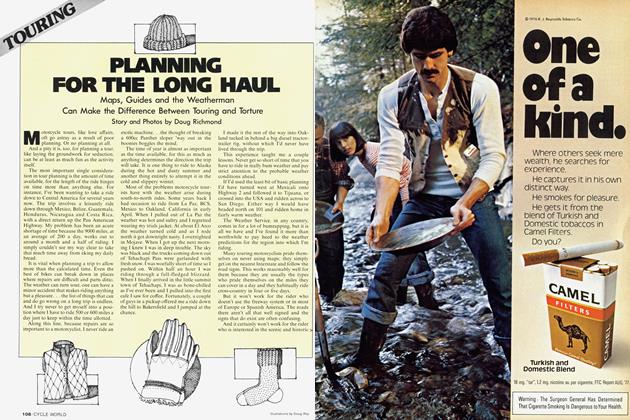

Travelling motorcyclists had best be prepared at all times to effect emergency roadside repairs. Touring is not like riding in circles around town or back and forth to the daily grind. The touring cyclist is always far from the friendly local dealer and his crew of happy parts-changers. And it has been thoroughly demonstrated that parking the bike by the side of the road and hitching a ride to the nearest parts supply is an open invitation to the first rip-off artist who happens along with a pickup truck. Just going to a strange town 60 miles away for a new master link will probably ruin what started out as a fine day's riding.

Fortunately the modern motorcycle seldom breaks down completely. Mostly it is usually something simple like a flat tire or a whiskered plug or a master link that has mysteriously decided to remove itself from service out in the middle of nowhere.

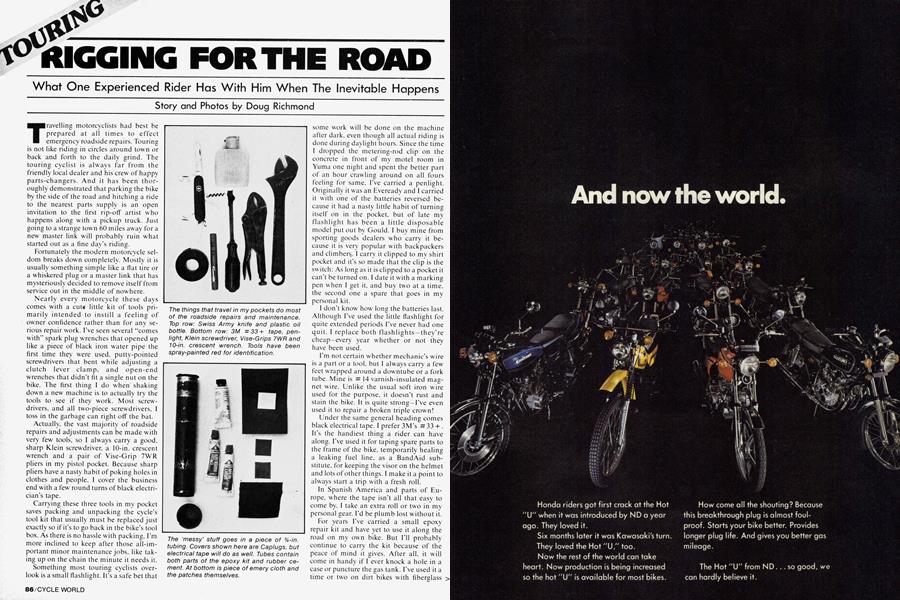

Nearly every motorcycle these days comes with a cute little kit of tools primarily intended to instill a feeling of owner confidence rather than for any serious repair work. I've seen several "comes with" spark plug wrenches that opened up like a piece of black iron water pipe the first time they were used, putty-pointed screwdrivers that bent while adjusting a clutch lever clamp, and open-end wrenches that didn't fit a single nut on the bike. The first thing 1 do when shaking down a new machine is to actually try the tools to see if they work. Most screwdrivers, and all two-piece screwdrivers, I toss in the garbage can right off the bat.

Actually, the vast majority of roadside repairs and adjustments can be made with very few tools, so I always carry a good, sharp Klein screwdriver, a 10-in. crescent wrench and a pair of Vise-Grip 7WR pliers in my pistol pocket. Because sharp pliers have a nasty habit of poking holes in clothes and people, I cover the business end with a few round turns of black electrician's tape.

Carrying these three tools in my pocket saves packing and unpacking the cycle's tool kit that usually must be replaced just exactly so if it's to go back in the bike's tool box. As there is no hassle with packing. I'm more inclined to keep after those all-important minor maintenance jobs, like taking up on the chain the minute it needs it.

Something most touring cyclists overlook is a small flashlight. It's a safe bet that some work will be done on the machine after dark, even though all actual riding is done during daylight hours. Since the time I dropped the metering-rod clip on the concrete in front of my motel room in Yuma one night and spent the better part of an hour crawling around on all fours feeling for same, I've carried a penlight. Originally it was an Eveready and I carried it with one of the batteries reversed because it had a nasty little habit of turning itself on in the pocket, but of late my flashlight has been a little disposable model put out by Gould. I buy mine from sporting goods dealers who carry it because it is very popular with backpackers and climbers. I carry it clipped to my shirt pocket and it's so made that the clip is the switch: As long as it is clipped to a pocket it can't be turned on. I date it with a marking pen when I get it. and buy two at a time, the second one a spare that goes in my personal kit.

I don't know how long the batteries last. Although I've used the little flashlight for quite extended periods I've never had one quit. I replace both flashlights—they're cheap—every year whether or not they have been used.

I'm not certain whether mechanic's wire is a part or a tool, but I always carry a few feet wrapped around a downtube or a fork tube. Mine is # 14 varnish-insulated magnet wire. Unlike the usual soft iron wire used for the purpose, it doesn't rust and stain the bike. It is quite strong—I've even used it to repair a broken triple crown!

Under the same general heading comes black electrical tape. I prefer 3M's #33 4-. It's the handiest thing a rider can have along. I've used it for taping spare parts to the frame of the bike, temporarily healing a leaking fuel line, as a BandAid substitute, for keeping the visor on the helmet and lots of other things. I make it a point to always start a trip with a fresh roll.

In Spanish America and parts of Europe, where the tape isn't all that easy to come by. I take an extra roll or two in my personal gear. I'd be plumb lost without it.

For years I've carried a small epoxy repair kit and have yet to use it along the road on my own bike. But I'll probably continue to carry the kit because of the peace of mind it gives. After all, it will come in handy if I ever knock a hole in a case or puncture the gas tank. I've used it a time or two on dirt bikes with fiberglass > tanks, but never on road machines.

The epoxy is carried in the same piece of VA-IN. thin wall conduit that protects my tire patching outfit. Nothing makes a bigger mess than epoxy or tire cement if it springs a leak and distributes itself all through the outfit.

It really isn't a part of my touring kit, for I'm never without it, but my Swiss Army knife has been a lifesaver time and again. Mine is a fairly small model with clip and spey blades, plus corkscrew, leather drill, can opener, bottle opener and screwdriver bit. I regrind the can opener and screwdriver blades to give a large and small screwdriver. A small oilstone in a plastic protective envelope goes in my kit. Most sporting goods stores have these.

A motorcycle engine in good repair seldom goes wrong, but every now and then a spark plug goes west. I'll never forget the time my BMW lost both plugs at the same time just as I started up out of a deep valley in Chiapas. It was about 120 F. in the shade and there was not a speck of usable shade within miles. Of course I had plugs, but installing new plugs in that hot engine remains one of the worst experiences of my motorcycling career.

With a four-cycle machine I carry a single change of plugs. With two-stroke bikes, I carry two changes. And I make it an ironclad rule to always replace plugs immediately. I've known riders who changed plugs and then a day or two later needed another plug and suddenly remembered they hadn't gotten new ones. Embarrassing . . . and a nuisance.

When I get a new plug I remove it from its box, gap it, and apply electrical tape to protect the points and keep dirt from working its way up around the insulator. To save room I don't replace the box as the tape gives all the protection needed.

Flat tires are funny-peculiar. A guy can ride for years and years and never have one and then have three or four within a couple hundred easy miles. Many riders install one kind or another of the proprietary sealants and swear by 'em, but I use nothing but air in my tubes. I did use sealant at one time, but when I got a puncture too big for the sealant to cope with I discovered to my eternal disgust that the patch wouldn't stick! It took hours and a whole tube of rubber cement to get the tube repaired. Since then I've relied on tire patching exclusively, although I'm told there are sealants on the market now that are chemically compatible with tire patching adhesives.

The last few years I've used Camel brand patches, but one make seems to be about as good as the next. There is one thing to look out for: Make absolutely sure that the patch kit is fresh, as both the patching material and the rubber cement seem to deteriorate with age. My practice is to replace the patch outfit every year.

The patching outfit goes in the Va-in. electrical tubing with the epoxy, along with a small piece of coarse emery cloth for preparing the tube for the cement.

You can't repair a flat tire unless you can get it off the rim. Most cycle dealers sell tire irons specifically designed for motorcycle use. These are the best investment a rider can make. They last two days past forever and largely eliminate pinched tubes. I've seen riders attack a flat with a couple of screwdrivers and wind up with more leaks than they started out with.

For some obscure reason most cycle dealers don't regard tire pumps very highly, and many don't even stock them. My current pump is one I bought from a bicycle dealer and it has lasted several years. One of my Hodakas came with a dandy little pump built along the same general lines as a bicycle pump but when it finally wore out the local Hodaka dealers were out of stock. I resorted to the nearest Schwinn dealer.

Most riders are aware of the practical necessity for valve stem caps, but generally content themselves with the plastic jobbies that came on the machine (if any). But I much prefer the type made of metal that not only seal in any possible valve core leakage but also double as core wrenches. Nothing is more irritating than to have to sit and hold a match or twig or something on the valve to let the air out when fixing a flat when you know that with the correct cap you could have unscrewed the valve and relaxed while the tube was deflating.

After a tire is patched the balance must be checked. Although there are balance weights especially made for motorcycles, I simply put a foot or so of Vs-in. solid or resin-core solder somewhere on the bike for re-balancing purposes.

Some part of the flat problem lies in the reluctance of most riders to replace casings before they're almost down to the cord. I figure out the length of a prospective trip and if I figure the tire won't go the distance I replace them before I start out. New tires are not as prone to punctures as well-worn tires.

continued on page 92

I don't carry spare tubes for ordinary touring. When I used to spend all my spare time riding Baja, back in the dear departed days before pavement, I usually taped a spare inner tube to the downtube just in case. But even in Baja I'll have to admit that I never used a tube.

Most tubes are ruined either because of a blowout, in which case a spare tube will be of doubtful help, or because the valve stem has pulled out. This last is extremely rare with modern tubes, and very unlikely with properly inflated tires on touring machines.

The electrics on modern bikes give very little trouble. But just to be on the safe side I carry a spare set of points and condenser if the bike I'm using has 'em, a few fuses, headlight bulb if used, a couple feet of # 14 automotive primary wire, and four or five Scotchloks, the little twist-on wire connectors used by electricians to make pigtail splices.

It is important to use only Scotchlok connectors, rather than one of the jillion or so makes of look-alikes; Scotchlok is the only wire nut I know of that will withstand vibration.

All the electric spares are packed in plastic foam and stuffed behind the headlight, inside the nacelle.

Many authorities advise taping spare cables alongside the regular cables. I used to follow this practice myself but stopped once and for all the day I caught the brake cable and the spare on a piece of pipe jutting out of the back of a pickup truck. The cable was jerked out by the roots and the spare taped alongside was kinked beyond use. Fortunately there was a simpático Islo dealer in town (Tuxtla Gutierrez) with facilities for making up cables. He had me back on the road in a jiffy.

My practice nowadays is to coil up a spare throttle and front brake cable and either secure them to the underside of the seat with tie wraps or to slide them between the springs and the padding.

Because a clutch cable is more of a convenience than a necessity to a motorcyclist I never carry a spare clutch cable.

Chains give very little trouble on touring bikes, but still and all, every experienced rider has had chain problems at one time or another. Once while riding in the low Sierras I picked up a small oak stick that got wedged between the case and the chain and shoved the master link out of its keeper. About a mile later the chain fell off and I thanked my lucky stars that I had a master link aboard.

There are almost as many places to carry spare chain links and master links as there are cycles. Many riders simply assemble the master links over a cable and let it go at that. Others put them in the tool compartment. I carry a single master link over a cable, and several more, together with several links of chain, in my personal kit as spares. I've never actually had occasion to use them, but having the spare along is wonderful for my confidence.

I've stopped and helped a number of touring riders afflicted with chain problems at one time and another. Either they didn't have spare master links, or they didn't have a chain breaker. Or both.

My pet touring chain breaker is the extremely compact Beaver Tooth. This is far and away the smallest breaker I've ever seen and takes up somewhat less room than the average spark plug. It is intended for emergency roadside repairs only, and cannot be reasonably expected to stand up to day in, day out professional shop work. When I get a new one I lubricate the screw's threads with Never-seeze before packing it on the bike. It's so compact that I can (usually) stow it in the tool compartment.

Most touring riders know about chain lubrication but now and then, I see a chain as dry as a Baja back road, so I'll touch on this hackneyed subject.

My favorite chain lube is 90 or 140 weight differential oil, aka "gear grease," which is readily obtainable anywhere. This is applied liberally with a squirt bottle. My current bottle is a 3 oz. plastic hair oil bottle with a spout that shuts off when folded over, small enough to be carried in a pocket of my riding outfit. In the rare instances when gear oil has been unobtainable I've also used ordinary motor oil. the heavier the better, with equal success. And I lubricate the chain each and every time I take on gas and at the end of the day's riding. Religiously.

As much of my touring nowadays is in Spanish America, where dirty gasoline is the rule rather than the exception, I've made it a practice for some years now to install a filter in the fuel line. These filters are sold at most cycle shops and auto parts stores and very rarely plug up, even with extremely dirty fuel. But when one does plug it can be restored to service by simply removing it and blowing through it backward. After clearing, it is vital to install it without reversing it in the line, otherwise the bits and pieces that weren't blown out are likely to work their way loose and wind up in the carb. This is in addition to the fuel filters installed by the manufacturers which, I've found by hard experience don't always work as advertised.