The Care and Feeding of the Motorcyclist's Camera

MOTORCYCLES AND CAMERAS go together like ham and eggs, and I suppose the problem of how to transport the latter on the former first came up about the time Harley met Davidson. Cameras are extremely allergic to vibration, dirt, moisture, dust and bumps and thumps — just the things that come naturally to motorcycles.

A motorcycle, by and large, is simply not the place for the fancy camera with all the latest gadgets — the general rule for machinery that the ruggeder the service the simpler the machine, goes double in spades for cameras for the motorcyclist.

There are styles in cameras, just as there are in dogs, liquor, women's fashions and women. Right now the huge 35-caliber single-lens reflex is all the rage. Most of them are obviously designed by the sales department, with the result that an inherently bulky design has grown to a completely unreasonable size.

But is was only a few years ago the small, compact camera, in assorted sizes and formats, was "in." Many of these cameras were, and are, beautiful examples of high precision manufacturing. Voitlander, Kodak, Mamiya, Zeiss, Ross-Ensign — nearly all the major manufacturers in-

cluded them in their lines. Now they're out of style and the used-camera shelves of large photo stores are full of them, from $30 to $70. When new, they cost up into the hundreds of big, fat dollars.

From the point of view of the motorcyclist, these little cameras are nearly ideal. They are light, compact, and in the highquality versions were equipped with good lenses and excellent shutters, coupled range-finders, double-exposure prevention and sometimes metering film advance. Almost without exception they did not offer interchangeable lenses, but do you need interchangeable lenses?

I have a whole battery of lenses and extension tubes for my 2-1/4 inch square single-lens reflex, but even so, the bulk of my photographs are made with the "normal" 80mm lens.

I'll be the first to admit that all these built-in attachments make fascinating reading in the photographic magazines, but the sad truth of the matter is that most of the little extras don't actually help the picturetaking one iota.

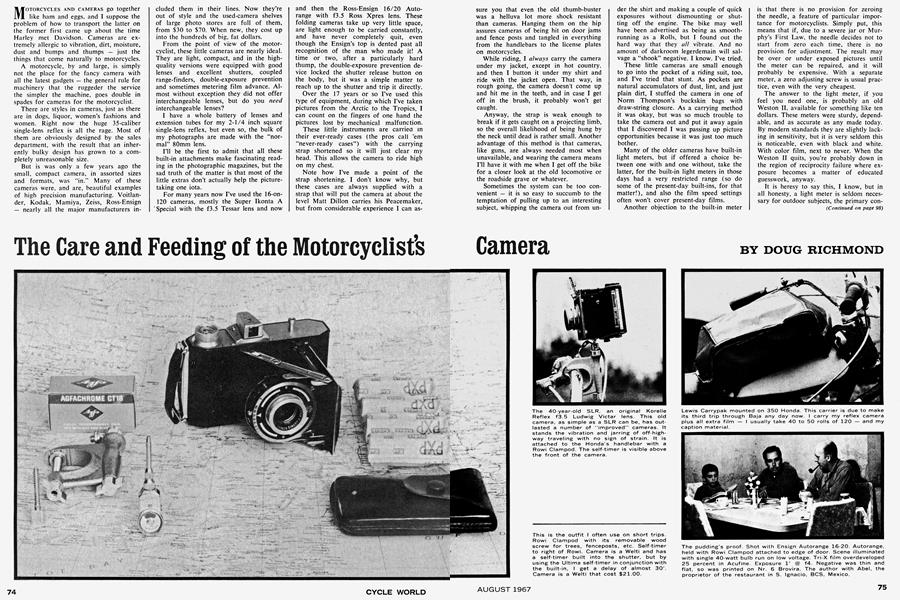

For many years now I've used the 16-on120 cameras, mostly the Super Ikonta A Special with the f3.5 Tessar lens and now

and then the Ross-Ensign 16/20 Autorange with f3.5 Ross Xpres lens. These folding cameras take up very little space, are light enough to be carried constantly, and have never completely quit, even though the Ensign's top is dented past all recognition of the man who made it! A time or two, after a particularly hard thump, the double-exposure prevention device locked the shutter release button on the body, but it was a simple matter to reach up to the shutter and trip it directly.

Over the 17 years or so I've used this type of equipment, during which I've taken pictures from the Arctic to the Tropics, I can count on the fingers of one hand the pictures lost by mechanical malfunction.

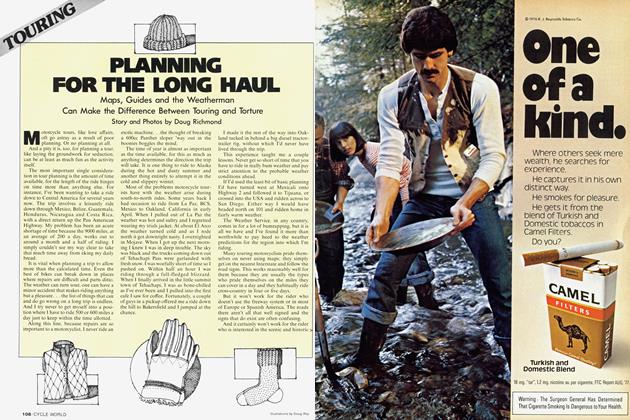

These little instruments are carried in their ever-ready cases (the pros call 'em "never-ready cases") with the carrying strap shortened so it will just clear my head. This allows the camera to ride high on my chest.

Note how I've made a point of the strap shortening. I don't know why, but these cases are always supplied with a strap that will put the camera at about the level Matt Dillon carries his Peacemaker, but from considerable experience I can assure you that even the old thumb-buster was a helluva lot more shock resistant than cameras. Hanging them on the hip assures cameras of being hit on door jams and fence posts and tangled in everything from the handlebars to the license plates on motorcycles.

DOUG RICHMOND

While riding, I always carry the camera under my jacket, except in hot country, and then I button it under my shirt and ride with the jacket open. That way, in rough going, the camera doesn't come up and hit me in the teeth, and in case I get off in the brush, it probably won't get caught.

Anyway, the strap is weak enough to break if it gets caught on a projecting limb, so the overall likelihood of being hung by the neck until dead is rather small. Another advantage of this method is that cameras, like guns, are always needed most when unavailable, and wearing the camera means I'll have it with me when I get off the bike for a closer look at the old locomotive or the roadside grave or whatever.

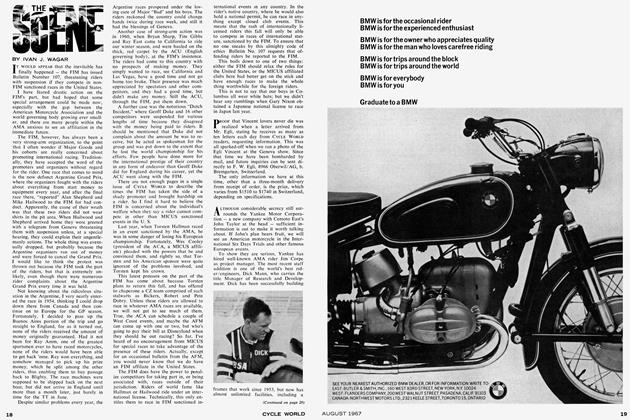

Sometimes the system can be too convenient — it is so easy to succumb to the temptation of pulling up to an interesting subject, whipping the camera out from under the shirt and making a couple of quick exposures without dismounting or shutting off the engine. The bike may well have been advertised as being as smoothrunning as a Rolls, but I found out the hard way that they all vibrate. And no amount of darkroom legerdemain will salvage a "shook" negative. I know. I've tried.

These little cameras are small enough to go into the pocket of a riding suit, too, and I've tried that stunt. As pockets are natural accumulators of dust, lint, and just plain dirt, I stuffed the camera in one of Norm Thompson's buckskin bags with draw-string closure. As a carrying method it was okay, but was so much trouble to take the camera out and put it away again that I discovered I was passing up picture opportunities because it was just too much bother.

Many of the older cameras have built-in light meters, but if offered a choice between one with and one without, take the latter, for the built-in light meters in those days had a very restricted range (so do some of the present-day built-ins, for that matter!), and also the film speed settings often won't cover present-day films.

Another objection to the built-in meter is that there is no provision for zeroing the needle, a feature of particular importance for motorcyclists. Simply put, this means that if, due to a severe jar or Murphy's First Law, the needle decides not to start from zero each time, there is no provision for adjustment. The result may be over or under exposed pictures until the meter can be repaired, and it will probably be expensive. With a separate meter, a zero adjusting screw is usual practice, even with the very cheapest.

The answer to the light meter, if you feel you need one, is probably an old Weston II, available for something like ten dollars. These meters were sturdy, dependable, and as accurate as any made today. By modern standards they are slightly lacking in sensitivity, but it is very seldom this is noticeable, even with black and white. With color film, next to never. When the Weston II quits, you're probably down in the region of reciprocity failure where exposure becomes a matter of educated guesswork, anyway.

It is heresy to say this, I know, but in all honesty, a light meter is seldom necessary for outdoor subjects, the primary concern of the motorcyclist. A little experimenting with the exposures recommended in the folder packed with the film will suffice quite well for a good 95 percent of all picture-taking.

(Continued on page 98)

A method of determining exposure that is very rarely publicized is very effective. On a sunny day, between 9:30 or 10 in the morning, and around 4:00 in the afternoon, with the sun behind or on either side of the photographer, the exposure is f 16 with a shutter speed of 1/ASA speed.

In other words, with a film with an ASA speed of 200, the exposure will be f 16 @ 1/200. If the sun is in front of the camera, give an extra stop or so — go to fil or f8. Shade the lens if possible.

This rough-and-ready system will give pretty good results. Before embarking on serious stuff, shoot a roll or two around the homestead, because all exposure data are merely suggestions and should be modified by the individual photographer to suit his equipment and working methods. With black and white you'll always wind up with printable negatives by using this formula, but with color you'll have a miss now and then, but you'll probably have an occasional miss anyway, even if you use the latest Spot meters! I've encountered several pretty good color photographers who base their exposures on this method for outdoor stuff.

Even if you use a camera with all the latest gadgets, or carry a fancy exposure meter, there always seems to come the time when the meter is left out of the kit, or its battery is flat, or the built-in meter goes on the hog, so it is pretty good to have something to fall back on.

And the little formula can save you a lot of that most valuable commodity — time. I'd like to have a peso for every minute I've waited while some camera bug diddled with the exposure meter.

When it comes to film, it is everyone to his own taste; but I personally recommend a slow-to-medium film for outdoor scenes, simply because with fast film on a bright day one winds up with over-exposure at 1/500 and f22, the fastest shutter speed (marked shutter speed, that is) and smallest stop generally available. This means that for all practical purposes it is impossible to use selective focus or selective shutter speed to concentrate interest on a foreground object, such as a pretty girl or a fancy bike, by throwing the background out of focus, or blurring the movement of the leaves in the picture.

On the other hand, very slow films are unable to see into the shadows very well, and particularly in the desert and at high altitudes, the shadows tend to go black and lose all detail.

Sky darkening and general contrast increasing is the most common use of filters in black-and-white photography, but I seldom bother with them. As far as I'm concerned, they are just that many more bits and pieces to pack around. I've found it is easier to burn-in a sky than it is to dig the filters out my pockets.

I did quite a bit of experimenting with filters for color work and came to the conclusion that the writers who recommend their use as a constant thing must be doing something I don't do, because I discovered that the UV's, etc, didn't do a thing I liked. I suggest you experiment a little yourself — anything you can eliminate while motorcycling is all to the good.

For color I use Agfachrome Daylight Reversal, simply because I like the color rendition — and the processing by Agfa — but if you're a dyed-in-the-wool color fan, you'll have your own preferences.

Regardless of the type of camera, I never never use a lens cap — I've seen more pictures completely lost through failure to remove the lens cap than any one thing. Most scratches on lenses are caused by improper cleaning, and anyhow, most folding cameras have a metal shield in front of the lens when folded. When unfolded it is for the purpose of taking pictures.

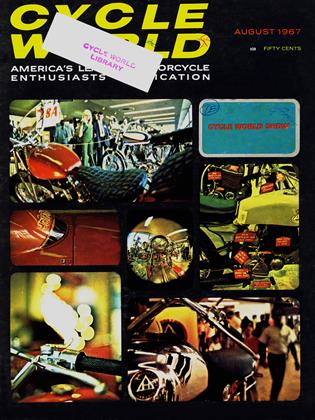

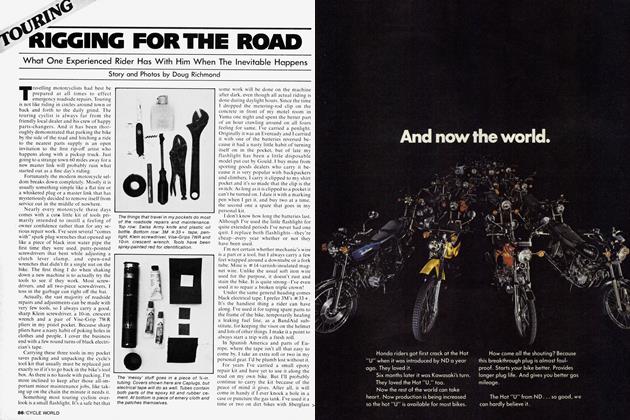

For the out-and-out camera bug who finds it necessary to carry a second camera or oodles of paraphernalia, the best answer seems to be the Carripak put out by D. Lewis, Limited. I paid $9.00 for mine four years ago and have used it on three Mexican trips. The Carripak is a bag with zipper closure that straps on the fuel tank. The zipper is covered with a hinged map holder of clear plastic that folds over the top of the Carripak and snaps at the bottom rear with three sturdy snap fasteners. The map-holder alone makes it worth hauling, but it is absolutely water-tight in actual use, and you know how hard it is to keep things dry on a bike in a driving rain!

As you may have surmised by now, by and large I'm against gadgets, but there are a couple of exceptions.

Most of the higher-quality folding cameras have a timing device incorporated in the shutter, allowing delayed action shutter release and permitting the photographer to include himself in the picture.

It has another use — it gives as nearly vibration-free shutter tripping as can be obtained, much steadier than manual tripping, even with a properly-used cable release. If the camera doesn't include this feature, I carry a $2.50 delayed action release in the same case in which I pack my Rowi Clampod.

The Clampod is a little C-clamp affair with a ball-joint camera holder. A woodscrew is buried inside the clamp which allows the camera to be mounted on fenceposts, stumps and the like. I've used the clampod directly on handlebars, luggage carriers, water pipes and such.

Although my remarks on cameras are aimed specifically toward the still camera user, they apply generally to the moviemaker, too.

One warm afternoon I encountered another oldish rider on a battered BMW up in Tioga Pass and stopped for a chat. We soon got around to talking photography, and he opened the front of his Barbour jacket to display a very experienced-looking Cine Kodak Special, slung 'round his neck on a length of web strap.

He told me he'd done a lot of experimenting over the years, but had never been able to evolve a better method of carrying a camera on a bike.

Neither have I.