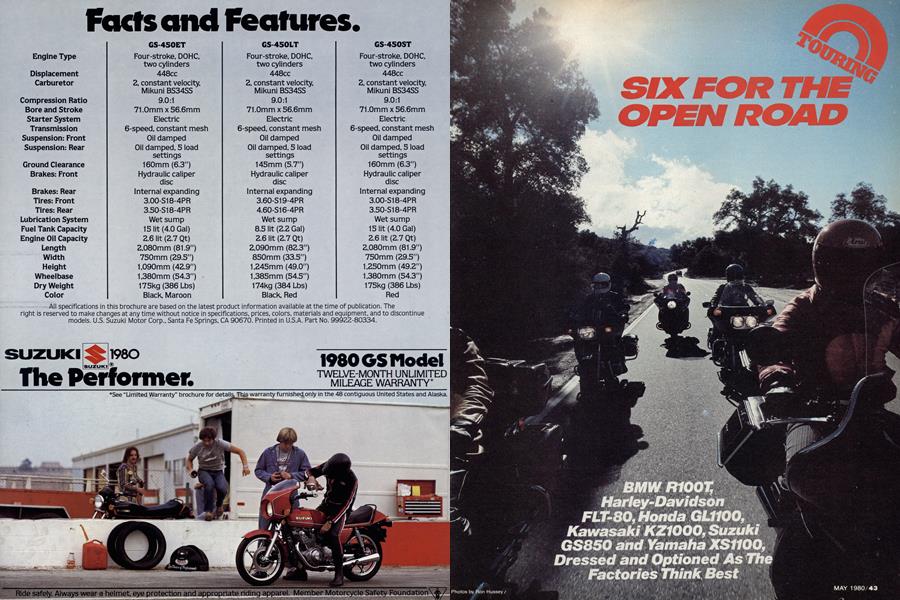

SIX FOR THE OPEN ROAD

BMW R100T Harley-Davidson FLT-80, Honda GL1100, Kawasaki KZ1000, Suzuki GS850 and Yamaha XS1100, Dressed and Optioned As The Factories Think Best

CYCLE WORLD TEST

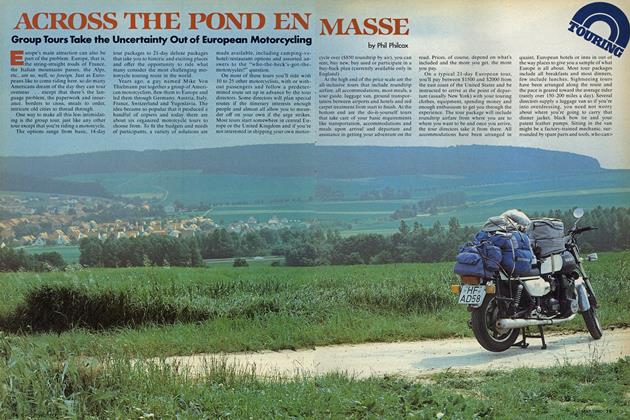

Imagine riding the best six big touring bikes available for a month; taking them on trips, taking them to the store, taking them for a Sunday ride. Finally, after thousands of miles and every possible performance test, there are four questions to be answered: Which bike would you choose to ride on a cross-country trip? Which would you pick for a Sunday ride? Which do you like best regardless of cost? Which, considering cost, would you buy?

Picking the best touring bike isn’t a matter of determining what’s fastest or what’s biggest or what’s cheapest. There’s more to it than that. Besides the quarter mile times and the roll-on tests and mileage figures and weights and measurements, there are subjective evaluations every rider makes. That’s why there are different approaches to the design of touring bikes: we don’t all go touring in the same manner.

But there are differences worth noting.

THE SELECTION

Not all of the touring machines available are that different. Yamaha’s XS1100, Kawasaki’s KZ1000 Shaft and Suzuki’s GS850 all have dohc inline four-cylinder engines set across the frames with a helical gear transmitting power from the transmission countershaft to a driveshaft on the lefthandside of the motorcycle. They’re air cooled, have four carbs, and 4-into-2 exhausts. They’re also good performing motorcycles with impressive quarter mile times in the stock form.

If the three inline Fours are almost identical, the other three bikes; the opposed Twin BMW R100T, the V-Twin Harley-Davidson FLT-80 Tour Glide and the opposed Four Honda GL1100 Gold Wing, are decidedly different. Different from each other and different from other motorcycles. The BMW is a lightweight, shaft drive sporting touring machine with long travel suspension and the simplest design. The Gold Wing, all new for 1980, is liquid cooled, complex, heavy, has an air assisted suspension and if it resembles any other touring bike, it would be the HarleyDavidson that’s even heavier and has an ohv 45° Vee of an engine that’s 1340cc, the largest of the test.

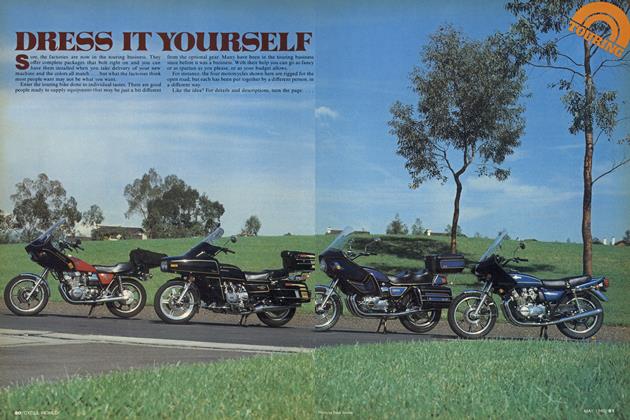

The six machines here were chosen for several reasons. First rule was that each would be equipped as the factory (or distributor) would equip it, for the open road and the long haul. Touring is a popular pastime and all the major factories are deeply involved. They are building or buying for sale under their labels the fairings, bags, etc., that formerly were ordered and installed after the machine itself was delivered. So it seemed appropriate that we use

bikes meant for touring and fitted out with the factory-approved equipment. (Later in this section we’ll deal with the bits and pieces.)

The six test machines here are not the only touring bikes on the market. They are in most cases the largest and/or the most specialized.

Several logical choices are missing. Kawasaki’s KZ1300 and the Suzuki GS1000G aren’t in the group because the importers didn’t have them available as ordered. The U.S. importer was not able to

provide a Moto Guzzi. So instead of having all the touring machines on the market, we have the six that were best equipped and on sale at the start of the season.

THE TESTS

No test or measurement can explain how a bike works on the road, but some can help you decide which motorcycles meet your needs. Some of the charts shown are obvious. Some aren’t. For instance, the sound level shown isn’t the usual stand-bythe-side-of-the-road-with-a-meter test. Instead, the sound meter was mounted to a rider while he rode each bike under identical conditions. The numbers indicate how much noise the rider heard on the various motorcycles. The 30mph and 60mph levels were taken with the bike cruising in high gear. The first gear reading was taken at maximum, full throttle acceleration.

Gas mileage figures were taken on a trip through Southern California, plus figures from the Cycle World mileage loop are included for comparison. Top speed fig-

ures are shown in comparison to the figures for un-equipped motorcycles and provide a measure of the wind drag of the equipment.

Roll-on tests were made using the CW computer test equipment, ensuring the results were accurate and impartial. Figures were taken with a single 170 lb. rider and two riders whose weight totals 350 lb., an amount representative of a fully loaded touring bike. All the figures were from high gear acceleration, from 30 mph to 80 mph. Relative differences can show if one mo-

torcycle runs particularly well at very low engine speeds or comes on strong only at high speeds. It’s a measurement that’s important because it gives a better indication of on-the-road power than do quarter mile times or dynamometer figures.

„ Load capacity is the difference between the manufacturer’s gross vehicle weight rating and the weight of the motorcycle with a half tank of gas and the accessories on it. Unlike the usual weights and figures, these include the weight of accessories, which take away from the load capacity.>

THE BIKES

BMW R100T

BMW’s middle bike, equipped with the Luftmeister fairing, BMW saddlebags, and top box is a bike of extremes. It has some of the best and worst features of the class. Light weight is its single best feature, giving easy handling on an open road and the ability (unusual in this group) to go down the occasional dirt road without trauma.

For 1980 the BMW gets a new air suction emission system, much like that used by Kawasaki. The air suction system allows richer jetting, which increases power while burning up excess fuel in the exhaust system. There’s also a new easy-change air cleaner assembly and the choke lever has been moved to the handlebars, from the lefthand side of the engine. Our test bike, had a 3.20:1 final drive ratio, the same as that used on the new R80 model and considerably different from the 2.91:1 used on the other BMW thousands. Sales brochures say the 1980 R100T still has the 2.91:1 ratio, so our bike could be a freak. In any case, the lower ratio improved low speed performance and helped make up for any loss of power due to the lower 8.2:1 compression ratio (down from 9.5:1) used on all 1980 BMWs.

Despite its obvious differences, the BMW is in many ways the most normal motorcycle of the test. It doesn’t have milewide handlebars or a two-holer double bucket seat. The pebble-grained seat was relatively flat and, though we’ve never been too fond of the BMW seat, this one was better than some of the other seats in the group.

Some of the other chronic BMW quirks were either less apparent in this test or mitigated by design. Take the sidestand, for instance. Normally the BMW sidestand is hard to extend, doesn’t allow the bike to lean enough to be stable on the stand and quickly springs up as soon as the motorcycle is touched. This BMW never fell over due to the sidestand, a record of sorts. It leans over more than usual and the stand stayed down once extended. It still isn’t convenient to reach and could be better, but progress has been made.

And the signal light switch, once an upand-down lever, is now a back and forth switch, similar to what most motorcycle companies use. Too bad it’s the hardest switch to reach on the left switch collar. The ignition switch is still on the lefthand side of the headlight housing and is difficult to reach with the fairing—any fairinginstalled. Getting to the fuses in the headlight shell is also more work than it should be.

Handling is a peculiar combination of nice and not-so-nice. For years everyone praised the BMW’s suspension as the most comfortable and best on a touring bike. But that was when Triumphs had little suspension and Harleys had none and there wasn’t much else. True, the BMW

has lots of suspension travel. Riding over the potholes of New York City or the frost heaves of British Columbia, the BMW suspension has an advantage over most street bikes. But the long travel isn’t well controlled and the motorcycle makes huge pitching motions whenever the brakes are applied. On a gently curving highway, where the elegant BMW can be steered with deliberation and the cornering demands aren’t of a race course level, the BMW is perfect. There’s adequate cornering clearance, certainly more than some of the bikes, and it’s stable; no wobbles or wiggles for the BMW, no sir.

On straightaways the BMW is still stable, though it’s likely to get blown sideways more by a wind than some of the bigger bikes. Around town the BMW doesn’t fare so well. Even the rider who likes BMWs and expected the R100T to be the ideal around town bike found the suspension allowed too much movement. When crossing dips in the road turning at intersections it can ground the sidestand far too easily because of the suspension travel. Lightweight or not, it’s just a bit clumsy around town and the close coupling of the rider

and passenger footpegs can make it hard for a rider with passenger to move his foot down when coming to a stop.

The engine conspires with the chassis to keep the BMW from being everybody’s favorite. Below 3000 rpm it pings even on good gas, despite the lowered compression ratio, and above 4000 rpm it gets harsh, moreso than the smaller BMWs. It’s happiest when ridden between 3000 and 4000 rpm, which demands use of the five-speed transmission. There’s good low speed power, but the throttle response wasn’t as snappy as many of the other bikes and the Beemer was sluggish around town when throttle response was critical.

Previous lOOOcc BMWs were geared exceptionally high so that fifth gear cruising meant leisurely and relaxed engine speeds. But with the low 3.20:1 gearing of the test bike, engine speed at 60 mph was similar to that of the multis. Being a Twin and having fewer power impulses, it was still more relaxed and less nervous feeling, but not as much so as other BMWs have been.

With gearing not much different from that of the Multis, the BMW performance indicates that it just doesn’t produce the same power as, for instance, the Kawasaki. At the lowest speeds in the roll-ons the BMW was excellent, but at higher speeds its torque couldn’t make up for the horsepower difference. Quarter mile performance was hindered by a clutch that slipped badly at the dragstrip. Even when the clutch diaphragm spring was replaced the clutch performance remained the same. ’Despite the problem, quarter mile times were on a par with the last BMW 1000 tested, an RT that was lighter and had higher compression. No doubt the lower gearing has maintained performance.

Getting underway with the BeeEm is harder than on any other motorcycle because of the clutch. Even after the faulty clutch diaphragm spring was repaired, the clutch wouldn’t engage smoothly and took hold with very little lever travel, a common BMW trait.

Brakes provided reasonable stopping distances only when the test rider used a King Kong grip on the dog-leg lever. With a cable linkage between the lever and the master cylinder that’s hidden under the gas tank, there are friction losses added to the system. In any case, this much pressure shouldn’t be necessary to stop a motorcycle this light. The drum rear brake worked fine and allows for easy rear tire changing, though.

BMW continues to provide numerous small but appreciated features like a tool kit that even includes tire changing and patching tools complete with air pump. There’s a 12v socket for accessories and the large tube backbone of the frame is open so a locking cable can fit right into the frame and not take up any storage space or interfere with riding the bike. The list of accessories offered by BMW and North American distributor Butler and Smith is huge. There are first aid kits and knee cushions and larger tool kits and extra instruments and even an intercom set. Of course there are the usual extras like fairings and saddlebags and trunks, and there’s even a vinyl shield that fits around the forks and fairing and eliminates the updraft and road spray common on full fairings.

Not only are there lots of accessories, but the basic bike handles accessories quite well. The 280 watt alternator has adequate power for most any electrical addition and the 28 amp battery is large enough to help. Mounts for the Krauser saddlebags come standard on the R100T and the bags themselves (see accompanying article, About the Accessories) are excellent. Even with a large fairing, saddlebags and top box the BMW’s handling wasn’t seriously impaired. No wobble or wiggle crept into the machine on tight corners and the accessories didn’t interfere with the enjoyment of the motorcycle as did some others.

Despite the light weight and stable road manners, the BMW is handicapped when it comes to two-up touring. With a half tank of gas and the accessories installed, there’s only another 308 lb. of load capacity left before the package is up to the gross vehicle weight rating. And with 300 lb. of couple on the bike it would bottom the rear suspension easily on dips and bumps, making loud graunching noises as the rear tire rubbed the fender. A standard size American couple would bring the bike up to maximum weight and there would be no capacity for gear.

Instead, the BMW is a solo tourer or a weekend bike for two-up use. It doesn’t appeal to the rider who enjoys carrying all the comforts of home and wants absolute luxury on the road. For the sports tourer, however, it may be the best of the bunch. The rider who tours on a Honda 400F and put low bars on his CB750 picked the BMW as the bike he’d choose for a crosscountry ride. His reason: “Most of its problems go away on the highway and the seat is better than a poke in the butt with a sharp stick.”

There was also one vote for the BMW as Sunday ride bike because of the generally good handling and the large 6.3 gal. gas tank providing the longest ride between visits to gas stations that are commonly closed on Sundays.

Does that make the BMW the best touring bike? No, but the BMW will continue to appeal to the few people who appreciate its unique qualities. >

HARLEY-DAVIDSON FLT-80 TOUR GLIDE

No laughing out there, please. The Harley-Davidson FLT really does belong in this test. To begin with, it should win the Most Improved Motorcycle award. Surprised? We were.

This isn’t the same Harley dresser we last tested. Fact is, there are only a few parts on this motorcycle that were used on Harley’s older Electra Glide. Only the 80 cu. in. V-Twin engine is shared with other Harleys and even that has had enough new pieces added to change its performance remarkably. The frame, with its extended box-section backbone holding a steering head quite upright so the offset triple clamps can turn easily, is not just new for Harley, it is a novelty for any motorcycle. There’s not even a center post for a seat spring and—better make sure Grandpa is sitting down—all the new frame and suspension pieces allow the graceful Hawg to lean waaaay over in the corners.

Underneath all the new pieces, there’s enough Harley so the Faithful won’t feel forgotten. Sitting on the low stepped seat, legs out in front with feet on the hinged floorboards, hands relaxed at the side while resting peacefully on the big handlebars, you know you’re on a Harley. If the new ignition switch (including fork lock) hasn’t been locked, no key is needed to turn it on and push the starter button and hear the big Twin rumble to life. At idle it even feels like a normal Harley, everything in motion, especially the engine. Then you heft the bike upright, fold back that wonderful locking sidestand (why can’t they all have one like that?), pull hard on the clutch lever, rev it up to, say, 1000 rpm and chug away.

But the Tour Glide is as different from previous Harleys as a Harley is different from other motorcycles and the differences become apparent once the huge ship is underway. So what if it weighs 781 lb? Accepting that nearly half a ton of man and machine can’t be hurried, piloting the FLT is delightful. Vibration fades away as the motorcycle picks up speed, the rubber engine mounts absorbing just the right energy so the engine doesn’t flop around and the whole bike vibrates no more than a steamship. The new five speed transmission shifts much more smoothly and quickly than the previous four-speed, though downshifts still bring about a noticeable klunk. Unlike so many of the high strung multis, the big Twin has no driveability problems. It starts in the morning and it runs when it’s hot and it never misses or coughs or lurches; the engine, instead, just does what the throttle grip tells it to do.

We won’t go so far as to say it handles like a sport bike, though Harley-Davidson will. Instead, it handles like a big athlete, the kind who plays the game because he’s big enough to do things smaller men can’t, yet he’s coordinated enough not to hurt himself. We never grounded anything on a corner. Harley-Davidson says the FLT has a lean angle of 35° loaded. That isn’t in the league with a Honda 750F that has 45°, but it’s on a par with the other big touring bikes.

Those six-ply Goodyears on both ends of the FLT would look at home on a Volkswagen, but on the Harley they take some getting used to. The profile is flat, so the bike wants to go straight and stay upright. Want to turn? Just push on the handlebars down by the knees. The bike turns. It doesn’t take, nor respond to, body English. It doesn’t even take much effort at the handlebars. With the offset triple clamps the FLT has a remarkably steep 25° steering head angle yet the trail is a longer-than-average 5.75 in. that makes for great straight-ahead stability. HarleyDavidson’s not the first company to use offset triple clamps (several Italian roadracers have used the idea), but the FLT is the only modern motorcycle to try the idea and the results are very good. Combined with the throttle set screw, it’s easy for a rider to cruise down the road with both hands off the bars, should one go in for that sort of thing.

Getting used to the handling isn’t so easy. First time Harley riders aren’t likely to lean the Tour Glide over much more than they would if riding on gravel. And the FLT doesn’t flick from side to side as do lighter machines. But given patience and practice the Harley can go down a winding road as fast as most touring riders would ever want to go. It’s surely fast enough to keep up with any group of touring riders.

Tires also limit braking ability. For the first time, a Harley-Davidson has enough brakes, triple discs with 352 sq. in. of swept area, to lock either end in hard braking. Brake lever pressure needed on the Harley is high. Not as much as the BMW. but more than that of the Japanese bikes. Harley has used brake pads with a high metallic content that work exceptionally well in the wet and these simply take more pressure to stop the bike. But they don’t fade and they do work when it rains and if a rider gets used to the Harley brakes, they are fine. Besides, during the braking tests, the Harley was the only bike that kept going straight when the front tire was locked. Sure is stable.

Like BMW, Harley-Davidson doesn’t play by anybody else’s rules so the Milwaukee gang is free to try things that may work better or worse. Things like the signal light switches. These are push buttons on the controls at each handgrip that trigger the blinkers when the button is held in. They’re great for lane changes on the freeway and never stay on after the bike is through the corner, but they aren’t as easy to use, in some situations, as the slide switches used on the other machines. Of course there’s the locking sidestand that doesn’t allow the bike to roll off and fall down. The instruments, a speedo, tach and warning lights, are mounted in front of the steering head in a large housing. They’re large, accurate, readable and especially readable at night when they light up bright but not enough to be irritating.

Not all of the Harley’s pieces are so good. No one liked the seat. No, it’s not because the seat isn’t sprung, it’s just too confining, not allowing a rider to move around with its shape that holds a rider in only one spot, and that not a very good one.

All the other touring bikes have shaft drive. Not the Harley. Shafts are heavy and expensive and take away power and it’s hard to change final drive ratios with a shaft. But chains are messy and don’t last as long and require maintenance. Harley’s answer is a chain enclosure. Just like what European transportation bikes and tiny Japanese tiddlers used 20 years ago. only updated. The chain case is a full enclosure, that is. it contains an oil bath so the final drive chain is always lubricated and never covered with dirt or water. Harley figures the chain should last at least 20.000 miles and the adjustment interval is extended considerably. It’s a good idea, it works and has anyone ever fixed a broken U-joint on a shaft drive bike with a master link?

Noise isn’t a problem on the Harley. There isn’t any. Noise is unwanted sound and the only sounds the FLT makes are joyous ones. In the sound meter test the Tour Glide had the lowest maximum first gear sound and readings comparable to the Yamaha XS1100 at cruising speeds. Only the BMW and Honda were any quieter and they were only slightly quieter at 60mph.

Unlike all the other bikes in the test, the Harley didn’t have any optional equipment on it. Yep. this was a stripper. The floor boards and heel-and-toe shifter and fairing and saddlebags and top box and crash bars and rack and seat are all standard. Are there options? Is a bear Catholic? Certainly there are options, a whole page of them. There are radios and CBs and gas gauges and highway pegs and instruments and lots of chrome covers for all the non-chromed parts of the bike. Without options the Harley is as fully equipped as most any touring bike gets. With options it’s a monument to Chromius, the Gaud of bad taste.

Rest assured the Tour Glide can handle the accessories. One wonders if it could handle without them. Designing a motorcycle knowing it’s going to have a fairing and saddlebags and a top box means the engineer doesn’t have to worry about weight distribution changes and variances in the center of pressure and all that technical stuff. Consequently the Harley is stable and the fairing doesn’t hurt the motorcycle in any way.

Being designed to carry two people and a kitchen sink, at 1180 lb. the Harley has the highest gross vehicle weight rating of any of the motorcycles. Even minus its considerable heft it has a load capacity of 400 lb., second highest of the test. Loaded to the gills it loses less than any of the other bikes, due to the low center of gravity and high initial weight. The load becomes a smaller part of the total.

The Harley deserves special mention for its two-up carrying capability. Back seat passengers generally rated the Harley the most comfortable of all the bikes. The seat was large and properly shaped. The backrest was positioned in exactly the right spot to lend support but didn’t interfere with passenger comfort. With the controlled vibration and pleasantly restrained sound, the Harley was an enjoyable traveling machine.

That Most Improved Motorcycle isn’t the only award the Tour Glide should get. In the voting the FLT was everybody’s choice when asked what motorcycle they liked regardless of cost. That’s especially shocking because there are several reformed Harley Haters around the office.

Only the Harley, when ridden down a straight highway, can make a rider smile. Nothing else feels or sounds quite like it, and when you ride a Harley, nothing needs explaining. It’s all said. You feel good just looking at it. But that’s not all.

Even on merit the Harley competes. It was one man’s pick for the Sunday ride and another said it was second choice for the Sunday ride because it’s so much fun to ride. Better yet, three people said they’d really like to take the Harley on the crosscountry trip if they only had a little more confidence in its ability to get there without requiring any maintenance.

See, the big Harley doesn’t have a reputation for being a maintenance free motorcycle and it does need a servicing every 1250 miles, according to the book, while some other bikes have a recommended service interval up to 7500 miles. Disregarding the concerns over service and reliability (only a balky trip odometer reset caused any problems during the test), the FLT would have been the top pick for the long haul. Amazing.

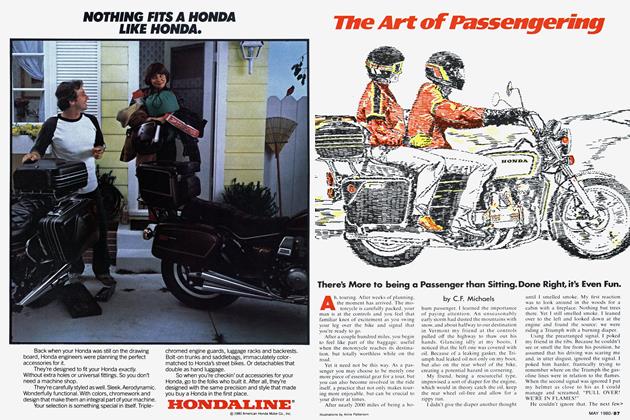

HONDA GL1100 GOLD WING

Call it technical onanism if you will, but Honda’s latest Gold Wing has every possible mechanical detail to be a stupendous touring bike. It’s liquid cooled so it’s quiet and doesn’t overheat and lasts a long time. Naturally there’s shaft drive and overhead cams, a huge plush double bucket seat and provisions for every accessory seen on the pages of Road Rider magazine.

Honda knows who buys Gold Wings and why and even what the bikes are used for once purchased. Consequently the GL is a highly concentrated bike specializing in highway luxury. For 1980 there’s an air assisted suspension at both ends, warning light included for when air pressure is too low. Just the ticket for maintaining control when there’s 400 lb. of load on the bike. The engine is bigger this year, and so are many of the small pieces in the drivetrain and frame so the bike is still in scale and a big scale it is, too.

Not only did the Gold Wing have a fairing and bags and rear box and crash bars, there was also an AM-FM stereo signal seeking digital waterproof shock resistant radio and intercom included. The altimeter, voltmeter, ambient air temperature gauge and quartz clock complete the Interstate package, Honda’s top-of-theline touringmobile.

There’s a fine line separating a real motorcycle from motorized bicycles and there’s an even finer, jagged line separating motorcycles from larger vehicles. For some staff members the Gold Wing passed over that line. If Harley’s unofficial motto is, “anything else is just a bike,” Honda’s motto should be, “anything else is just a motorcycle.”

At 737 lb. the Honda wasn’t the heaviest bike, nor was it the longest. Still, a person with a tape measure could make some money betting riders that the GL wasn’t the biggest touring bike of the test. It felt bigger than any of the others.

Maybe it was the Harleyesque front fender or the wide handlebars or the huge seat, but sitting in the Honda, riding it around town, gave an impression of enormity. Engine shape has something to do with it. With the flat Four there’s no room beside the engine for the rider’s feet, so the footpegs are moved behind the cylinders with the shift lever tucked up under the lefthand cylinders and the brake on the right. Of course the seat must be moved back so the pegs aren’t too far aft and then the handlebars have to stretch aft far enough for a rider to reach, so the amount of motorcycle sticking out in front of the rider is imposing.

There are reasons for the engine configuration. It’s wonderously smooth and lowers center of gravity so even with accessories perched way up high the overall center of gravity is reasonable. But the demands made on rider position are excessive. Most of the test riders complained about the riding position on the Gold Wing. Most riders didn’t like the seat, which was large and soft enough, but it also restricted riders to one seating position. On long rides it’s nice to be able to move around. The Gold Wing’s seat is adjustable fore and aft, but on the Interstate the bolts that hold the seat are next to impossible to reach with the saddlebags in place. All riders agreed the seat was best left in the aft position so the footpegs are farther forward in relationship to the seat. That also moves the rider farther from the handlebars.

By far the most notable ergonomic horror are the crash bars. Crash bars, though the factories don’t call them that, aren’t a bad idea. It’s just that the Honda’s bars stick outboard of the cylinders so far, and extend so far back past the cylinders that it’s impossible for a rider to move his leg without his shin hitting the bars. No one was able to ride the Gold Wing without bruising his shins and that’s just not acceptable.

Just because nobody was comfortable sitting on the Gold Wing doesn’t mean it’s not a comfortable motorcycle. It is. Makes about as much noise as an overhead fan. The ride is as soft as a feather bed. Combined with the excessive heat held in by the fairing lowers, riding the Gold Wing is reminiscent of spending a night in a Far East hotel room.

Which is not to say riding the GL isn’t a pleasant experience. It’s pleasant not because of what you feel when riding it, but because of what you don’t feel. Cruising down the road at any speed there’s just no vibration. The next smoothest motorcycle is only that smooth with the engine shut off. It’s so smooth that when the throttle is closed and the Hy-Vo primary chain rattles a little bit the effect is exaggerated.

This is also the quietest bike going. At 30 mph the sound level is the same as the BMW and H-D and it’s only 1 decibel quieter at full throttle acceleration than the BMW, but it’s noticeably quieter at normal cruising speeds from 50 to 75 mph.

Handling isn’t the Gold Wing’s forte. Neither is it a problem. At the softest suspension pressures the GL grounds easily, scraping the footpeg and centerstand on the left and the crash bars on the right, especially with a passenger aboard. With the suspension pumped up to maximum pressure cornering clearance goes from poorest to not bad. Whether pressure is low or high the motorcycle is stable. It doesn’t wallow. It doesn’t wobble. It can be blown around by high winds and passing trucks, but its actual cornering speed is quite respectable for its size.

Performance is also so-so on the GL. In stock trim the Honda has impressive quarter mile performance and good acceleration at low engine speeds. But the Interstate tested didn’t run well at the dragstrip. Under hard acceleration the engine would miss as though the carbs were starved for gas. As a result the figures show the Honda being noticeably slower than the Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki. Even in roll-on tests the Gold Wing performed

more like the Suzuki and Kawasaki than the other 1 lOOcc motorcycle. Part of the diff erence may be the 100 lb. of accessories the Honda carried, but this particular Gold Wing just plain didn’t run as well as the bike tested earlier. On the road, performance isn’t a concern. The GL is plenty fast enough for carrying people down the highway at any speed they choose.

Only the fuel consumption and gas tank size limits the Gold Wing’s high speed cruising ability. The Interstate went 38.8 mpg on any fuel we could find. Again, that mileage was on a highway trip and a previous GL1100 got better mileage on the CWcity/highway mileage loop. Run until the fumes cry uncle, the Wing will go 205 miles on a tank at normal speeds. Mileage drops sharply at high elevations or when running fast, another consideration. A 200 mi. range isn’t good on a motorcycle designed explicitly for touring. That’s only two-thirds as far as the BMW will go and less than any of the touring bikes except for the Kawasaki, which has a 184 mi. range.

Though it can’t go far between gas stops,

it can run for 7500 mi. between scheduled maintenance. Now that the points have been replaced by an electronic ignition the spark plugs are the only electrical part needing service and the tappets are the only other maintenance concern.

With lighter accessories (the Interstate was 100 lb. heavier than a stock GL1100) the Honda’s load capacity would have been higher. Still, it had a respectable 368 lb. rating. Equipped more like the other bikes it would have had a load capacity on par with the Harley-Davidson. That load carrying ability, combined with the broad powerband and stable handling make the GL an excellent two-up tourer. Passengers generally thought better of the seat than the driver did and the suspension is simply the best of the bunch.

It’s that super suspension, combined with the bike’s absolute trouble-free nature and lack of serious vices that make it the highway favorite of the test. Every test rider but one chose the Honda as the bike for a cross-country jaunt. And all those riders complained that the seat wasn’t right. When it comes time for that mad rush to Daytona and back the Gold Wing will surely be the bike picked because it’s the most comfortable, has less serious quirks and you know you’ll get there.

Everybody appreciated the Honda’s sheer competence on the highway but there wasn’t much affection for the GL. It wasn’t the bike ridden around town and it wasn’t taken for a thrash through the mountains. Honda named it the Interstate and it’s named right.

That’s where it belongs.

KAWASAKI KZ1000 SHAFT

Kawasaki’s shaft drive 1000 is a great bear of a motorcycle. It’s big and strong and does its job in a brutal, honest fashion. If this thing came with a bumper sticker, it would say “My other Peterbilt is a truck.”

It’s basic. An air cooled dohc inline Four operating a five-speed transmission with a shaft drive. Two valves in each cylinder, one carb per piston. Has as many surprises as an unwrapped Christmas present.

Instrumentation consists of a speedometer and a tachometer and a fuel gauge. No turn signal canceller or beeper. No air assisted forks. No adjustable damping. Suspension adjustment refers to setting the preload on the shocks.

Special features on the Kawasaki are things like electronic ignition, carburetor accelerator pump, hidden seat lock, tubeless tires, starter-clutch interlock, four-way flashers, detachable kick starter and the locking gas cap. This isn’t exactly a nofrills motorcycle, but it has less of a plastic feel than some of the more ornate machines.

Potential is what the Kawasaki has. The engine works just as it should, starting instantly with full choke, running without complaint when it’s cold, accelerating hard or easy without any stumble or hesitation and responding precisely to what the right handgrip told it to do. The slide throttle carbs don’t have the jerky response of the CV carbs used on many other motorcycles, while the accelerator pump takes care of low speed throttle response. And because the Kawasaki uses an air suction emission system the carbs can be jetted for best running instead of emissions.

Power? This is a Kawasaki 1000, after all. Aren’t they synomymous? Only the Kawasaki KZ1000 Shaft thrusts the front wheel in the air during quarter mile runs. Performance testing the Kawasaki was easy. There’s no technique involved. Just rev up the engine a little and dump the clutch and away you go. The engine doesn’t stall and the clutch doesn’t slip. Anyone can get good performance out of the Kawasaki. It’s easy.

Even the transmission helps the bike perform. None of the touring bikes shifted as well as the Kawasaki. It never missed shifts or slipped out of gear. Lever pressure was light. The entire motorcycle felt as though a day at a dragstrip, a week for that matter, couldn’t harm it.

Like the engine, the suspension is the same kind of no-nonsense equipment. Done right, a touring bike suspension would work well without unnecessary adjustments. Kawasaki, though, hasn’t done it quite right. There’s lots of travel in the forks, 7.9 in. to be exact. In back there’s 4.5 in. of travel, surely enough to absorb any highway bump without having too stiff a ride. Unfortunately the rear springs are too soft, allowing the Kawasaki to bottom on minor bumps with a single rider and assuring bone-jarring bottoming when a passenger or load is along. Spring rates for the forks are better, but these too are soft, allowing excessive motion when the brakes are applied. Better damping or slightly stifler springs in front would improve the motorcycle.

Carrying capacity of the Kawasaki is good. It’s a match for the loaded Honda Gold Wing, very close to an average for this group. With the accessories on the bike the Kawasaki became the longest motorcycle overall, due as much to the Vetter trunk as anything else. It was also wide, with the saddlebags sticking out more than any of the others. At 39 in. from edge to edge, the bags on the Kawasaki were 9 in. wider than those on the Suzuki and BMW.

One place the KZ lacked carrying capacity was the gas tank. On our highway ride the Kawasaki got the worst gas mileage, 38.3 mpg, and it also had the smallest gas tank with 4.8 gal. capacity. Having an inadequate capacity and range would be bad enough but the Kawasaki tank was shaped so the rear portion of the tank was wider than the front. That made for an awkward seating position because a rider couldn’t keep his legs in out of the breeze; the wide tank forced the rider’s legs too far apart.

Discomfort continued to the seat. Riders who didn’t like the two-holers thought the Kawasaki seat might please them until they sat on it. After a ride one person said the only reason the seat was upholstered was to keep it from rusting.

The seating position on the Kawasaki was fine. Pegs were comfortably located for all, the strangely normal handlebars didn’t bring any complaints. Controls worked well except for the throttle that had a much too stiff spring. Return springs this stiff aren’t necessary on any motorcycle and are just plain unacceptable on a touring machine. Nuff said.

Of the six motorcycles, the Kawasaki was the least touring oriented. What it felt like was a performance motorcycle. Even in performance, however, the Kawasaki didn’t work as well as it should have. Its quarter mile times were on a par with the smaller engined Suzuki that weighed nearly as much. Roll-on performance, again, felt good, but the numbers were a match for the Suzuki at most speeds. Because the slide throttle carbs on the KZ don’t limit air velocity, hard acceleration from low speed requires careful modulation of the throttle.

Handling was sub-par too. At high speeds the Kawasaki would wiggle a little bit even in a straight line. During dragstrip testing the handlebars would be moving back and forth slightly by the end of the quarter mile and in top speed runs it wasn’t as stable as most of the other motorcycles. On back roads, the kind of roads motorcyclists look for and car drivers look out for, the Kawasaki was happy if not pressed. Ridden at a leisurely pace, leaning it over no more than 15 or 20°. the KZ was stable and secure. At a sporting pace, the kind of pace that has cars squealing and motorcyclists grinning, the Kawasaki was uncertain. It would lean over and then pick itself up. It was impossible to hold a cornering angle with it. Nothing dragged because nobody trusted it enough to drag

anything. Even the roadracer on our mountain ride asked the tourguide to hold the pace down because he was riding the Kawasaki. Raingrooves also made the KZ wiggle.

Around town, though, the KZ1000 was pleasant enough. The engine helped here, because several of the other motorcycles had difficulty running when first started. Going around corners at intersections and maneuvering through the parking lot was no problem with the KZ. It didn’t fall into turns and considering its size, required little effort to turn. No wonder it got frequent use when people needed a motorcycle for trips to the bank or to take to lunch. That suited the KZ.

What hurt the Kawasaki more than anything else was the vibration and sound it made at cruising speeds. At 30 mph it was the noisiest of all the group. The bike goes through several stages of howling and moaning and sounding lonesome, with all that noise hitting the rider in the face. Without a fairing the Kawasaki doesn’t have much of any noise, but with the

fairing to block wind noise and the sounds being bounced back by the fairing, the din is awful.

Vibration, though, is worse. Maybe the accessories make the vibration seem worse than it is, but the Kawasaki was definitely the worst buzzer of the test. Cruising down the freeway at 65 mph the Kawasaki sends up a vibration that’s guaranteed to tickle your fancy. At other speeds the butt massage is reduced by other parts vibrating. Everywhere on the Kawasaki things vibrate and the tingling bombards the rider and passenger every minute they spend on the motorcycle.

Kawasaki should rubber-mount the engine. Not like the Harley rubber mount, but like the Honda CB900 rubber mount. Four-cylinder inline engines naturally produce torsional vibration. Some, like the Yamaha, damp it with mounts. The Suzuki is small enough not to have a problem.

Conspiring with the engine is a drive ratio that makes the engine spin 3873 rpm when the bike’s going 60 mph. The Kawasaki has enough power: It doesn’t need that low a gearing. Geared up so the engine could relax and turn a slower speed the bike would be much more comfortable and more economical too.

As it is, the Kawasaki was the least liked touring bike of the test. Get rid of the vibration, quiet it down, gear it up, put on a bigger gas tank and stiffen up the rear springs and the KZ would be great.

For sporting riding Kawasaki makes the chain driven KZ 1000s. It’s a shame the Shaft isn’t turned into a touring bike. It’s got enormous potential.

SUZUKI GS850

Being the smallest bike in the test, displacement-wise. should have been a liability to the Suzuki GS850 in a test like this. After all, these are touring bikes, by definition if such a definition exists, large ungainly monsters dedicated to the principle that bigger is better. Yet when all was said and done, the Suzuki’s size was more an advantage than a disadvantage.

Based partly on Suzuki’s GS750 and partly on the GS1000, the shaft drive Suzuki certainly came with sporting credentials. It was geared lower than any of the other bikes to give the smaller engine some leverage. Its short stroke dohc inline Four should have been able to rev higher and might return better gas mileage this year with the new CV carbs and electronic ignition. When the first GS850 was tested last year we were impressed with the comfort and performance of the bike, but put off by some severe drivability problems. With the new carbs and ignition, we thought, the problems might be solved.

Somehow the Suzuki’s smaller size has been well hidden. Even without a top box. the Suzuki weighed 649 lb., only 14 lb. less than the Yamaha XS1100. And the Suzuki’s accessories looked smaller than some of the other bikes, with the saddlebags tucked in nice and close and the smaller fairing being narrower and lower. We never did find out where all the weight is.

The Suzuki may be heavier than it should be. but no one who rode the bike guessed that it weighed as much as it did. Its handling was more like that of a good 750 than a touring bike. It didn’t have to be wrestled into corners and held down or picked up and muscled around. Light pressure on the bars shot the message straight to the frame that the rider wanted to change directions. Not only was it the best handling bike in the test, it’s a fine handling bike. Even the addition of the fairing and saddlebags didn’t detract from the quick response and precise steering.

On mountain roads the Suzuki rider was the fast rider, leading the pack down the highway. It’s so willing to go around corners it entices its rider into enjoying sinfully fast riding. Rain grooves didn’t bother it. nor did bumpy corners or high speed straights. A cross wind at the racetrack couldn’t interfere with the Suzuki’s top speed run because the bike was so stable.

Unlike some of the bikes, the Suzuki's adjustable suspension isn’t there to compensate for problems; it’s there to help a rider find the combination of damping and spring rates that works best. None of the settings work poorly. With minimum air in the forks and the shocks set at the softest damping positions the ride was soft but the handling was still precise. With a load on the bike the forks worked better with higher air pressure and stiffer damping made the bike feel more secure, but the difference was a matter of individual pref-

erence. not absolute necessity. It was always comfortable.

A frame that keeps the Suzuki handling well with a load also makes load carrying safer and more enjoyable. Though the load capacity of the bike was second lowest of the test at 354 lb., the Suzuki lost less of its nimbleness with the addition of a passenger than any of the other motorcycles. Differences in load capacity between the Suzuki. Kawasaki and Honda were slight to begin with.

Part of the Suzuki’s exceptional performance with accessories added stems from the nature of the accessories. Look at the chart showing top speed and the Suzuki’s is the second fastest. That’s a particularly good test of the wind resistance of the accessories and the Suzuki’s accessories added less drag than any of the others.

Of course the Suzuki was also an excellent track performer. Some of the bikes, the Honda for example, didn’t perform as well on the track as they did on the highway. The Suzuki was the opposite. In quarter mile performance it was virtually the equal of the Kawasaki and performed considerably better than the much larger Honda GL1100. That lower gearing, high

revving engine, good clutch and easy controllability helped the bike perform better than several larger but less sporting machines.

Braking performance was as good as engine performance. It was the only bike tested with noticeably shorter braking distances than the others. Even with the load of equipment it stopped in 138 ft. from 60 mph, better than many unequipped motorcycles. The brakes are strong and feed back a feel of the front tire and the tires have excellent grip, yielding the short stopping distances.

As good as the track performance was, day-to-day engine performance left a lot to be desired. As a touring bike the Suzuki’s engine characteristics were terrible. At low throttle openings and low rpm, especially anything below 3500 rpm, the engine would miss on one or two cylinders. The Suzuki would stutter and miss at normal engine speeds until the engine was spinning fast enough, and the throttle opened enough, then the bike would rocket forward. It felt as though the bike had twostage carbs with a secondary barrel opening up once the bike was moving. A characteristic CV carb jerkiness remained at all times, though the Suzuki’s drivetrain doesn’t have any sloppiness that adds to the problem.

Lean carburetion is most likely the cause of the Suzuki’s engine troubles, but it didn’t return good gas mileage. On the highway the Suzuki would go 40 miles on a gallon of any kind of fuel we found, but that’s not exceptional. At least the gas tank was larger than average at 5.8 gal. And. unlike some of the other new Suzukis. there’s still a reserve position on the vaco uum operated petcock on the GS850. Still, a range of 232 mi. isn’t anything to write home about and the Suzuki should do better.

While throttle response was the Suzuki’s most frustrating problem, it’s a problem that could be solved with some carburetion work. Its noise problem is another matter. At 60 mph the Suzuki was twice as loud as the next loudest motorcycle. Part of the reason is the gearing that makes the engine run faster than the other bikes at cruising speed, but that’s not the entire problem. The Suzuki’s engine produces more noise than the other engines. The primary drive gears are noisy and there’s intake noise and there’s other mechanical noise. A different exhaust wouldn’t solve the problem. And it is a problem. An hour’s ride on the Suzuki was enough to make most people want to get off the bike and rest their ears. Acceleration noise was even worse. With a reading of 114 db(A) on the sound meter, the Suzuki was twice as loud during maximum acceleration as the next loudest Yamaha. The type of sound contributed to the irritation. The Suzuki’s road sound wasn’t as enjoyable as the Harley’s quiet rumble or even the BMW’s muted exhaust note. This isn’t the sound of an engine doing work, it’s the sound of an engine room on a steamship.

Without a fairing the Suzuki’s sound wouldn’t be as objectionable. The fairing cuts down wind noise and bounces engine noise back and there’s no escape. A fullface helmet with an Apple Warmer closing off the bottom reduced the sound, but it was still there.

Maybe nothing could be done about the noise, but something could be done with the seat other than sitting on it. The stock Suzuki GS850 has one of the best seats on a motorcycle. It’s wide and relatively flat and very soft and everyone who rode the stock 850 liked the seat. Back in the college dorms guys used to sneak up behind their friends, grab the back of the underwear and give it a sharp tug. This was called a “snuggie” and this is what the Suzuki’s optional seat does to the rider. There’s no big hand grabbing at your shorts, instead the first hole slopes forward so the rider is constantly sliding down toward the front where the seat slopes up and crushes one’s manliness. This seat must have been designed by the fellow who came up with the Honda’s crash bars. Do you suppose he’s responsible for the BMW’s sidestand?

Other than the seat, the Suzuki’s riding position was fine. The bars didn’t offend anybody and the simple instruments (a gas gauge in addition to the tach and speedo) were pleasant. One man found the shifting to be notchy but others liked the positive shifting of the Suzuki.

One big advantage of the Suzuki is its price. At $3099 for the stock bike the Suzuki was $550 less than the next least expensive. That’s quite a bargain for a motorcycle that’s fun to ride and performs as well as the Suzuki. Because several people felt the carburetion could be fixed and the noise could be lived with and everything else is really exceptional, the Suzuki was the pick for Best Value. When asked what bike they’d buy if they were paying for it, the Suzuki was everyone’s pick.

One rider also chose the GS850 as his Sunday Ride bike because of its better handling and smaller, lighter feeling. The Suzuki has its problems, but they can be lived with or corrected. The carburetion is the worst problem, but there are fixes. What Suzuki needs to do is quiet the motorcycle and fix the carbs. >

YAMAHA XS1100

Having been named Cycle World's favorite touring bike for the past two years in a row, the Yamaha XS1100 came to the office faced with high expectations. We knew it was enormously powerful and had a huge load carrying capacity and had a nice soft ride, but we had never ridden a full dress Eleven. Would a full dress Yamaha work as well as a stock XS1100?

Now that there are other 1 lOOcc motorcycles and even a 1300cc Six available, the XS1100 doesn’t seem as huge as it used to. Equipped as it was, the Yamaha wasn’t the largest motorcycle. Weighing 663 lb. the XS was lighter than the Kawasaki and only 14 lb. heavier than the Suzuki 850. It was 74 lb. lighter than the full dress Honda. Even in figures like overall length and width the Yamaha measured up about in the middle of the pack.

Of the Japanese touring bikes, the Yamaha is the only one that drew comments about its attractiveness. The two-tone grey paint was tasteful and good looking. The accessories matched the original color and looked good on the motorcycle. There wasn’t too much chrome and no part of it had that Made in Japan look that occasionally mars the styling of otherwise good bikes.

Styling aside, the Yamaha is noteworthy because of its engine. Two years ago the XS1100 was amazing because of the enormous torque at low speeds and the peak horsepower the air cooled, dohc inline Four produced. All that power at every engine speed doesn’t come from trick items like six cylinders or a 16 valve head. It comes from good sound engineering. The only novelty in the engine is the vacuum advance unit on the ignition. Other than that, and even the Honda GL1100 now uses a similar ignition advance, the XS1100 is all straightforward stuff, no different from the KZ1000 or the GS850.

Power is this bike’s specialty and power is everywhere. The Yamaha was the roll-on champ with one rider or a full load. The Yamaha was the quarter mile winner and it had the highest top speed. Best of all, it was easy to use the Yamaha’s power. Where the Suzuki had to be pushed to go fast and the Kawasaki felt powerful and brutal, the Yamaha never lost that soft feeling. The test rider, after the quarter mile runs, suspected the Yamaha’s time wouldn’t be any better than the Kawasaki, yet the difference was substantial. Rather than spinning its tire or jerking the front end in the air, the Yamaha just sort of gathers up its skirt and hurries along to the end of the strip, having picked up all that speed in the process.

Yamaha has also done a good job of making the engine run while meeting emission requirements. Full choke and the engine fires up instantly. Instead of spin-

ning the engine at 4000 rpm with full choke as some of the bikes do, the Yamaha choke allows the engine to run at a pleasant enough speed, around 2000 rpm. It can be ridden away as soon as started without trauma.

Normal CV carb throttle twitchiness is a slight problem for the Yamaha, but it’s not as serious a problem as it is on the XS750 or XS850. There are no flat spots in acceleration and the engine responds to throttle twisting at any engine speed.

While the clutch has a light pull and holds up well to hard use, the Yamaha’s transmission is not an easy shifting unit. A loud clunk accompanies each shift and it’s normal to miss the third to fourth shift if shifting isn’t done slowly and deliberately. Shifting is the Yamaha’s only real drive train problem and the enormous torque of the Eleven’s engine makes shifting optional much of the time.

Besides the incredible power, Yamaha has done an excessive job of making the XS1100 comfortable. The suspension isn’t just cushy, it’s mushy. And the suspension is particularly overworked with accessories installed and loaded. Minimum air pressure in the forks and the lightest damping on the adjustable damping rear shocks

(installed on both the standard and special this year) make the XS ride like a cloud. Unfortunately, it also handles like a cloud and have you ever tried to steer a cloud?

The softest settings of the Yamaha’s suspension make it wallow at speeds touring riders normally see. Going onto the Interstate at the cloverleaf the Yamaha would lean over and then stand up, not able to maintain a constant angle. No one scraped anything on the Yamaha because no one trusted it not to fall over and therefore wouldn’t ride it hard enough to scrape.

At least this is one motorcycle that has suspension adjustments worth having. Pump up the forks with 20 psi of air and the front end lifts an inch. Set the shocks at the maximum of the four settings and things settle down remarkably.

Even at the firmest settings the Yamaha was the least confidence-inspiring machine on a twisty road. The front end falls into corners at low speeds and requires more effort to turn at high speeds than the other bikes. At least the stiffer settings minimize straight line wiggles the Yamaha occasionally had.

. Comfort requires more than a plush suspension and the Yamaha scores well on rider and passenger seating. It offered the only bucket seat that people thought was comfortable. Unlike most of the other double buckets, the Yamaha seat didn’t slope forward. It was soft, yet offered support, low enough so the rider could control the bike at low speeds. The handlebars irritated several riders and the grips, with a flared end, griped riders because their hands rested on the flared end of the grips. Footpegs were in the right place, the instruments were readable and the throttle return spring was manageable. The Yamaha, like the Gold Wing, is an Interstate armchair. Only the Yamaha is more like a motorcycle with a conventional motorcycle design and conventional motorcycle feel.

BMW

R100T

$7936

Harley-Davidson

FLT

$6013

Honda

GL1100

$5473

Kawasaki

KZ1000

$4690

Suzuki

GS850

$3765

Yamaha

XS1100

$4756

One of its biggest features is cargo capacity. This was the highest in the test at 427 lb., more than the Harley-Davidson and more than the Honda Gold Wing. It didn’t have the greatest gross vehicle weight rating, but the Yamaha is lighter than the other super size touringmobiles. Considering its less than precise handling, the Yamaha didn’t suffer too badly with the addition of more weight.

Adapting well to carrying big loads doesn’t mean it adapts well to carrying accessories. There are some problems with the bike when accessories are installed, at least the accessories Yamaha installs.

When the motorcycle was first delivered, test riders were put off by a loud resonance at 55 to 58 mph. It felt like a mighty rattle of some piece of the motorcycle and the reverberations extended through the entire machine. Checking fairing and lowers and saddlebags and every other piece we could didn’t turn up the villain. The loud rattle persisted throughout the test, but riders accepted the noise more as they rode the bike.

Another strange noise occurred at higher speeds, anywhere from 65 to 80 mph and not always at the same speed. This was a howl that sounded like King Kong blowing across the top of a 10 ft. Coke bottle. It was another awful, irritating sound that made riders immediately complain about the Yamaha and avoid riding it. Neither of these sounds was heard on any stock Yamaha XS1100. And while the rattle doesn’t appear to be created by the accessories, the accessories either cause or amplify the sounds. We can’t say whether other accessories would encourage these sounds to the same extent, but it remains a concern.

Between resonant frequencies the Yamaha is a generally quiet place to sit. At 30 mph it’s nearly as quiet as the quietest bikes. At 60 mph it’s as quiet as the Harley and significantly quieter than the other inline Fours. Only at maximum first gear acceleration is the Yamaha loud and that’s not a big problem.

Vibration control on the Yamaha is very good. It’s not a Gold Wing, but it’s smoother than either of the other inline Fours and it has the largest engine so Yamaha must be doing something right. As long as speed is held above the 55 mph buzz and below the 65 mph howl, it’s a peaceful highway tourer.

Perhaps we were expecting too much of the Yamaha this time around. So it isn’t as silky smooth as the Gold Wing or as sporting as the Suzuki. After we got over an initial disappointment with the Yamaha’s handling and the irritating noises we began to rediscover its charms. Power corrupts and the Yamaha is the most corrupt motorcycle of the test. Ridden at the right speed it’s comfortable and smooth and pleasant. The few irritations it has are things we can live with or work around.

When it came time to pick favorites the Yamaha was a strong second to the Gold Wing for the cross country ride. People who weren’t sure about riding the Harley on a long trip picked the Yamaha as the second choice. Even the rider who liked the BMW best chose the XS1100 as a second-place machine.

Of the conventional design motorcycles the Yamaha is the highway champion. And it’s still competitive with the other bikes when it comes to pure comfort.

Now if they’d tighten up the handling and put on a bigger gas tank. ... >

CONCLUSION

Surprisingly, there is a high degree of agreement among the riders. What works, works for everyone and what doesn’t work is apparent to all. But touring is not as easy to define as touring bike and picking an overall winner wouldn’t be fair. Instead, there are class winners.

What most commonly is thought of as the best touring bike, that is, the best highway cruiser, is the Honda. It’s designed for the job and offers qualities that none of the other bikes can offer. It’s the cross country champ and if we had to pick an overall winner, this is the category we’d consider the championship.

Harley-Davidson, at the beginning of this test, was awarded the Most Improved Motorcycle award. The FLT also is Miss

Congeniality. It was the motorcycle we all liked the most, the one we tried to keep for ourselves on the long ride. It was fun and we enjoyed every minute spent on it.

Suzuki makes the most sporting touring bike, or maybe that’s because the GS850 isn’t just a touring bike. It’s also a sports bike that happens to have a shaft. Whatever it’s called, with a list price of $3099 it’s also a bargain. Give it the Value for Money award.

Yamaha still makes the most powerful touring bike and an excellent all-around tourer. Along with the Harley-Davidson, it deserves an honorable mention for crosscountry cruising. It may not offer the maximum in comfort any more, but the tremendous engine is enough to make us admire it.

BMW will have a small but stable market for their unusual combination of attributes for as long as they want. Nobody else makes a lightweight shaft drive touring bike, let alone a bike with the BMW’s simple design. For occasional unpaved roads no other touring bike can match the BMW and its large gas tank and good mileage make it the cruising range champ, all important considerations for some people. The BMW certainly has its niche.

Kawasaki, sad to say, is the only motorcycle in the test that doesn’t have a niche. It’s got enormous potential with a strong, reliable engine, but it doesn’t have a specialty as do the other motorcycles. Perhaps this motorcycle was designed by people who don’t ride touring bikes.

And now for the accessories. SI