TURNED LOOSE ON NUMBER ONE

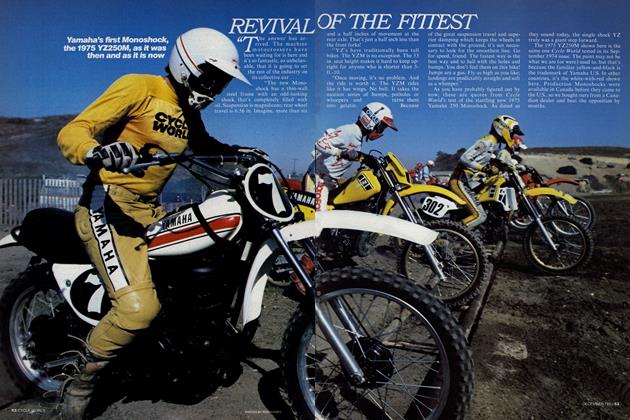

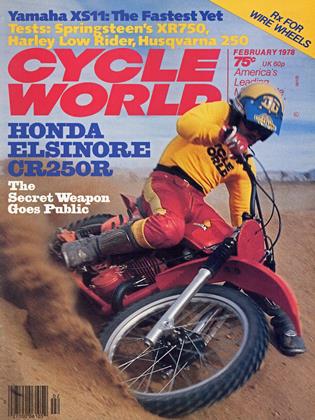

Tony Swan

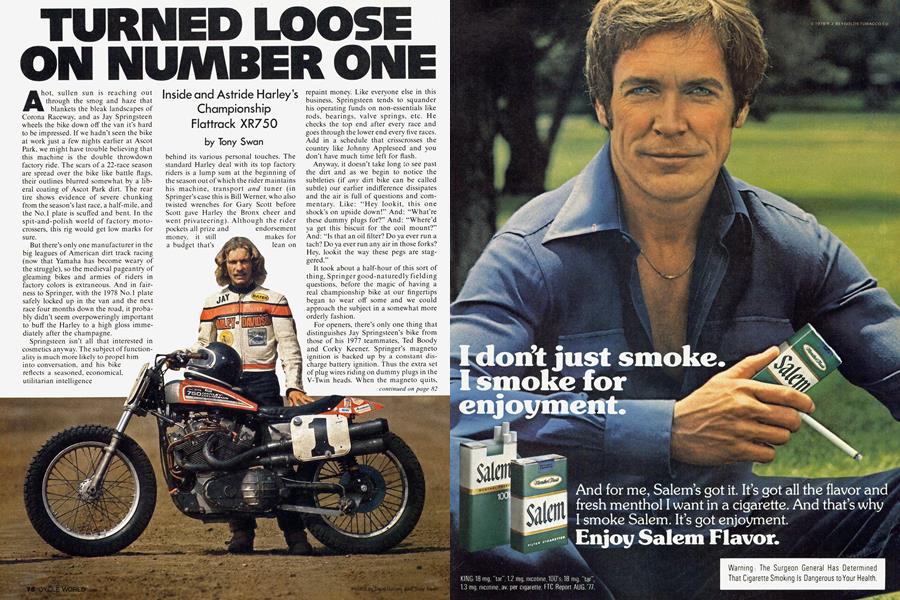

Inside and Astride Harley's Championship Flattrack XR750

A hot, sullen sun is reaching out through the smog and haze that blankets the bleak landscapes of Corona Raceway, and as Jay Springsteen wheels the bike down off the van it's hard to be impressed. If we hadn't seen the bike at work just a few nights earlier at Ascot Park, we might have trouble believing that this machine is the double throwdown factory ride. The scars of a 22-race season are spread over the bike like battle flags, their outlines blurred somewhat by a liberal coating of Ascot Park dirt. The rear tire shows evidence of severe chunking from the season's last race, a half-mile, and the No.1 plate is scuffed and bent. In the spit-and-polish world of factory motocrossers, this rig would get low marks for sure.

But there's only one manufacturer in the big leagues of American dirt track racing (now that Yamaha has become weary of the struggle), so the medieval pageantry of gleaming bikes and armies of riders in factory colors is extraneous. And in fair ness to Springer, with the 1978 No.1 plate safely locked up in the van and the next race four months down the road, it proba bly didn't seem overpoweringly important to buff the Harley to a high gloss imme diately after the champagne.

Springsteen isn't all that interested in cosmetics anyway. The subject of function ality is much more likely to propel him into conversation, and his bike reflects a seasoned, economical, utilitarian intelligence behind its various personal touches. The standard Harley deal with its top factory riders is a lump sum at the beginning of the season out of which the rider maintains his machine, transport and tuner (in Springer's case this is Bill Werner, who also twisted wrenches for Gary Scott before Scott gave Harley the Bronx cheer and went privateering). Although the rider pockets all prize and endorsement money. it still makes for a budget that's lean on repaint money. Like everyone else in this business, Springsteen tends to squander his operating funds on non-essentials like rods, bearings, valve springs, etc. He checks the top end after every race and goes through the lower end every five races. Add in a schedule that crisscrosses the country like Johnny Appleseed and you don't have much time left for flash.

Anyway, it doesn't take iong to see past the dirt and as we begin to notice the subtleties (if any dirt bike can be called subtle) our earlier indifference dissipates and the air is full of questions and com mentary. Like: "Hey lookit, this one shock's on upside down!" And: "What're these dummy plugs for?" And: "Where'd ya get this biscuit for the coil mount?" And: "Is that an oil filter? Do ya ever run a tach? Do ya ever run any air in those forks? Hey, lookit the way these pegs are stag gered."

It took about a half-hour of this sort of thing, Springer good-naturedly fielding questions, before the magic of having a real championship bike at our fingertips began to wear off some and we could approach the subject in a somewhat more orderly fashion.

For openers, there's only one thing that distinguishes Jay Springsteen's bike from those of his 1977 teammates, Ted Boody and Corky Keener. Springer's magneto ignition is backed up by a constant dis charge battery ignition. Thus the extra set of plug wires riding on dummy plugs in the V-Twin heads. When the magneto quits, which happens frequently, Werner and/or Springsteen simply swing the number plate out and begin switching over. As Springsteen noted, the change can be made on-track, which is “a lot quicker than having to come into the pits” and infinitely quicker than having to go through a complete magneto change. We were fortunate enough to see this switch made twice, once at Ascot just prior to Springer’s qualifying heat in the TT and once at Corona during our test session. If Springer and Werner had been forced to try a magneto swap at Ascot, they’d have been out of the show. But the switch to the battery takes about two minutes, and once we’d watched Springer go through it at Corona (after the bike quit on our test ed in the middle of Turn 4), we wondered why they bother with the magnetos at all.

continued on page 82

Down to basics. All factory XR750s are handed out with the same frame, which is made by Champion. Anyone can buy the same frame, according to Springsteen. (As far as getting consumer model XR750s is concerned, better get your order in now— for the 1979 season. According to sources inside the Harley conspiracy, there will be exactly 100 XR750s available for the 200 buyers who want one this season.)

The frame on Springer’s bike (it’s one of three; he has another half-mile/TT bike as well as one set up for miles) has been heavily gusseted at the swing arm pivot point, and there’s also extra bracing around the rear motor mount, which has a tendency to crack, particularly in TTs. Everything is heavy duty, of course, and singularly without frills.

Both the frame and the swing arm offer two mounting positions for the S&W freon bag shocks, and yes, one is upside down. Springer figures they work better upside down, and admits he also likes the effect this odd combination has on first-time observers—“freaks ’em out,” he says. The left side shock is mounted conventionally to keep the freon bag away from the heat of the exhaust pipes. He has a heat shield on his mile bike, and this lets him run both shocks upside down.

Up front are Ceriani road racing forks, fastened into a 26-deg. head angle. Springer keeps a book on the various tracks, and this steep rake gives him the kind of quick steering he wants at a track like Ascot, although he adds “there really isn’t anyplace else like Ascot.” At any rate, the rake can be altered by moving the Cerianis up and down, giving Springer all the geometry he needs for a season on the circuit.

A beefy steering damper on the left side of the bike says something about how the machine works going straight ahead, and there are adjustable rubber snubs on the steering locks to ward off tank slappers. Tucking in is just a matter of grabbing whatever’s available on this bike, but on the mile machine Springer has a hand grip fastened onto the left side just below the handlebars.

continued on page 88

The bars themselves are chrome-moly, patterned after a popular K&N Products model. They sweep back and afford plenty of leverage. A toggle switch kill button is mounted near the end of the left bar.

The footpegs (both spring-loaded and safety wired), are staggered, and the left one has migrated around on the bike considerably since Springer first joined H-D, traveling as far aft as the swing arm before drifting forward again to its present mounting position at the back of the cases. The brake pedal and shift lever (borrowed from a Sportster somewhere along the way) are both mounted on the right side of the bike, which seemed like an awkward arrangement until Springer told us his racing technique was to get into fourth gear as soon as possible and stay there the rest of the way. This gives him better bite coming out of the turns and he thinks it makes the motor live longer, since at more than 5000 rpm the engine gives all the power he can get onto the track anyway.

“Even in fourth gear 1 can spin the tire halfway down the straights,” he says.

Aside from the back-up ignition system there isn’t much to distinguish the bike’s electrics, although there is a nice little rubber biscuit slung from the underside of the backbone just ahead of the tank to cushion the coil from the engine’s vibrations. Springer and Werner have also doped out a neat interconnecting fuel line setup, a legacy of the 1976 Peoria TT when Springer had a petcock quit feeding while he was leading the race. Too much gas can be as big a problem as too little, and Springer guards against this with some stout rubber bands to hold the choke levers down on the 36mm Mikuni carbs.

Instead of an oil cooler, Springer uses an oil filter on the Harley, its extra capacity obviating the need for the cooler.

A diamond #520 chain sends power to the rear wheel—we’d expected to see some-thing a good deal heavier—and it spins a sprocket that’s been cut down considerably to save weight.

Depending on track conditions. Springer’s Harley will wear either Goodyears, Pirellis or Carlisles, favoring the last two on the more slippery circuits.

The technically oriented reader may notice a certain sparseness of detail concerning the XR750 engine. This is not quite an omission. More in the nature of a trade secret.

AMA rules require the 750s to be production engines, in this case production meaning a run of at least 200. Harley does meet this rule. The factory doesn’t go much beyond the rule, that is, the XR750 is not a de-stroked Sportster engine in a special frame.

The XR750 did begin life that way. When the AMA changed the rules and allowed overhead valves for 750s, H-D kept in the game for one year with 750cc versions of the then-new 883cc Sportster engine. Since then the XR has been mostly alloy. It’s sort of based on the street engine, being of course the 45-deg. ohv V-Twin, etc., but the XR engine is built for racing and sold only to racers.

The outside is fairly well known, i.e. two carbs, tuned exhausts, two ignition systems, one of which works. And the Harley engineering department says the XR engine, complete with everything except exhaust pipes, weighs 175 lb. while the lOOOcc Sportster engine, with electric start and all, weighs 202 lb. Not the difference the layman would expect.

Inside the engine is something else. No other motor sport pays as much tribute to the tuner, for what looks like good reason. Professional boat racers buy and discard surplus engines. The Formula One car chaps buy their engines from outside suppliers, in fact half the rival teams buy their engines from the same supplier.

The AMA wrenches and tuners, though, all begin with the basic Harley XR package and tune from there. Within the prescribed limits of bore, stroke, stock cylinder head casting and a few other items, Werner and rivals are free to hone, stroke, persuade, bully and massage their handmade units into works of privately held art.

Further, Werner and peers don’t just build a racing engine. They build a selection of XR750 engines, in as many variations as there are AMA-recognized tracks.

For the Astrodome, tightest of all and with next to no traction, Werner may give Springsteen a grunter XR, all torque and no more than 60 bhp.

For a mile track with a tacky surface, that is, a track that needs all the power the tuner can provide, Werner’s magic shop delivers a high-rev engine with 90 bhp and nothing under 4000 rpm. Or something like that, Werner not being anxious to discuss details.

In short, what we could see, Jay would talk about. If we couldn’t see it, we weren’t told about it, which struck us as being a fair restriction. There always is next year.

And that’s yr. winning Harley XR750. Not as exotic as we maybe expected but even with Werner’s wizardry the XR says a lot about young Jay. He wins against a flock of guys whose tuners begin with pretty much the same equipment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsThe Troubleshooters

February 1978 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1978 -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

February 1978 By A.G. -

Roundup

RoundupShort Strokes

February 1978 By Tim Barela -

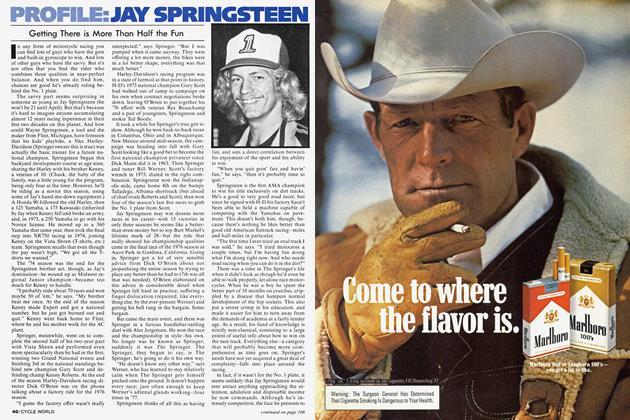

Features

FeaturesProfile: Jay Springsteen

February 1978 -

Competition

CompetitionThoughts From the Back of the Wrecker

February 1978 By Peter Vamvas