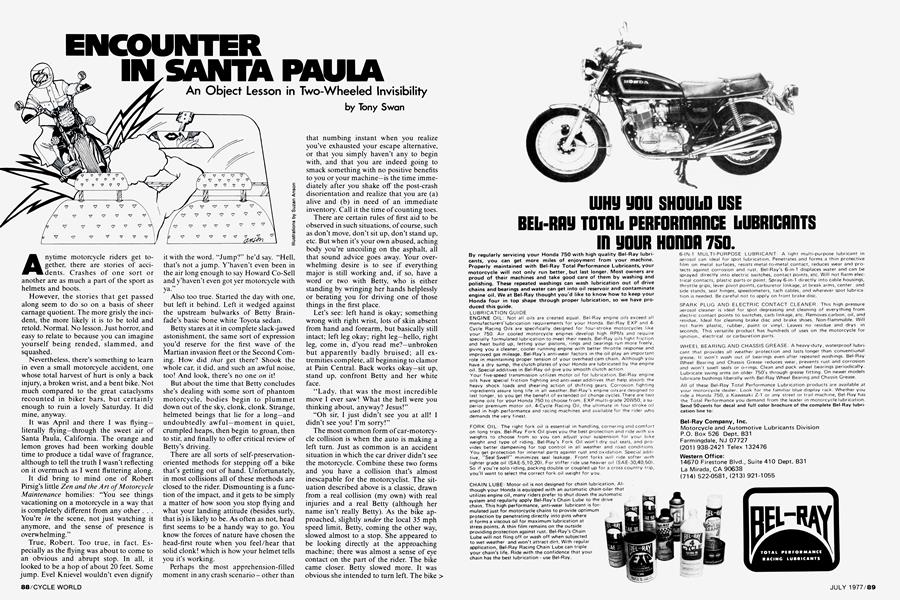

ENCOUNTER IN SANTA PAULA

An Object Lesson in Two-Wheeled Invisibility

Tony Swan

Anytime motorcycle riders get together, there are stories of accidents. Crashes of one sort or another are as much a part of the sport as helmets and boots.

However, the stories that get passed along seem to do so on a basis of sheer carnage quotient. The more grisly the incident, the more likely it is to be told and retold. Normal. No lesson. Just horror, and easy to relate to because you can imagine yourself being rended, slammed, and squashed.

Nevertheless, there’s something to learn in even a small motorcycle accident, one whose total harvest of hurt is only a back injury, a broken wrist, and a bent bike. Not much compared to the great cataclysms recounted in biker bars, but certainly enough to ruin a lovely Saturday. It did mine, anyway.

It was April and there I was flying— literally flying—through the sweet air of Santa Paula, California. The orange and lemon groves had been working double time to produce a tidal wave of fragrance, although to tell the truth I wasn’t reflecting on it overmuch as I went fluttering along.

It did bring to mind one of Robert Pirsig’s little Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance homilies: “You see things vacationing on a motorcycle in a way that is completely different from any other . . . You’re in the scene, not just watching it anymore, and the sense of presence is overwhelming.”

True, Robert. Too true, in fact. Especially as the flying was about to come to an obvious and abrupt stop. In all, it looked to be a hop of about 20 feet. Some jump. Evel Knievel wouldn’t even dignify it with the word. “Jump?” he’d say. “Hell, that’s not a jump. Y’haven’t even been in the air long enough to say Howard Co-Sell and y’haven’t even got yer motorcycle with

ya.”

Also too true. Started the day with one, but left it behind. Left it wedged against the upstream bulwarks of Betty Brainfade’s basic bone white Toyota sedan.

Betty stares at it in complete slack-jawed astonishment, the same sort of expression you’d reserve for the first wave of the Martian invasion fleet or the Second Coming. How did that get there? Shook the whole car, it did, and such an awful noise, too! And look, there’s no one on it!

But about the time that Betty concludes she’s dealing with some sort of phantom motorcycle, bodies begin to plummet down out of the sky, clonk, clonk. Strange, helmeted beings that lie for a long—and undoubtedly awful—moment in quiet, crumpled heaps, then begin to groan, then to stir, and finally to offer critical review of Betty’s driving.

There are all sorts of self-preservationoriented methods for stepping off a bike that’s getting out of hand. Unfortunately, in most collisions all of these methods are closed to the rider. Dismounting is a function of the impact, and it gets to be simply a matter of how soon you stop flying and what your landing attitude (besides surly, that is) is likely to be. As often as not, head first seems to be a handy way to go. You know the forces of nature have chosen the head-first route when you feel/hear that solid clonk! which is how your helmet tells you it’s working.

Perhaps the most apprehension-filled moment in any crash scenario - other than that numbing instant when you realize you’ve exhausted your escape alternative, or that you simply haven’t any to begin with, and that you are indeed going to smack something with no positive benefits to you or your machine—is the time immediately after you shake off the post-crash disorientation and realize that you are (a)

alive and (b) in need of an immediate inventory. Call it the time of counting toes. There are certain rules of first aid to be observed in such situations, of course, such as don’t move, don’t sit up, don’t stand up, etc. But when it’s your own abused, aching body you’re uncoiling on the asphalt, all that sound advice goes away. Your overwhelming desire is to see if everything major is still working and, if so, have a word or two with Betty, who is either standing by wringing her hands helplessly or berating you for driving one of those things in the first place.

Let’s see: left hand is okay; something wrong with right wrist, lots of skin absent from hand and forearm, but basically still intact; left leg okay; right leg—hello, right leg, come in, d’you read me?—unbroken but apparently badly bruised; all extremities complete, all beginning to clamor at Pain Central. Back works okay—sit up, stand up, confront Betty and her white face.

“Lady, that was the most incredible move I ever saw! What the hell were you thinking about, anyway? Jesus!”

“Oh sir, I just didn’t see you at all! I didn’t see you! I’m sorry!”

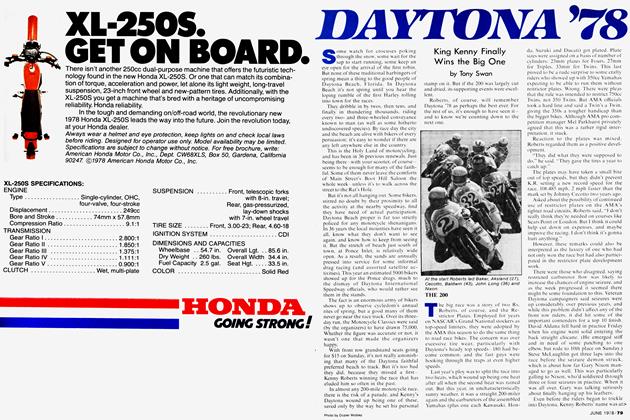

The most common form of car-motorcycle collision is when the auto is making a left turn. Just as common is an accident situation in which the car driver didn’t see the motorcycle. Combine these two forms and you have a collision that’s almost inescapable for the motorcyclist. The situation described above is a classic, drawn from a real collision (my own) with real injuries and a real Betty (although her name isn’t really Betty). As the bike approached, slightly under the local 35 mph speed limit, Betty, coming the other way, slowed almost to a stop. She appeared to be looking directly at the approaching machine; there was almost a sense of eye contact on the part of the rider. The bike came closer. Betty slowed more. It was obvious she intended to turn left. The bike > came closer still-maybe 40 feet away. Betty slowed and stopped. She must see it, right? Big bright headlight.White helmets. And the bike, a Honda GLIOOO, is harder to miss than most. With perhaps 30 feet to go, no doubt remains. Betty sees. Betty knows. Betty will stay put and not spoil this fragrant day.

Wrong. With an ambush instinct that would be more at home in Rhodesia or Northern Ireland, she lunges into the path of the oncoming bike. No time for anything but the merest touch of brakes before impact. It turns out that Betty is coming home from work, and the turn she’s making is into her driveway. In cases like that, the vision of most drivers gets to be extremely selective. Betty was seeing only her driveway and the prospect of getting home to relax. It would have taken something much bigger than a motorcycle to catch her eye.

The point is this: We all have our Bettys out there waiting for us somewhere, and in many cases it won’t be a situation quite so benevolent to the motorcyclists as this one was. Approach speed could easily have been higher, for example, or the car might center-punch the bike rather than vice versa.

I recall a conversation with a gas station attendant a day before departing on this ill-starred voyage to the threshold of Betty’s driveway. He was talking about a nasty accident he’d seen a day or two earlier involving a bike and a left-turning vehicle.

“See, what happened is the driver didn’t even see the guy,” he said.

“Yup,” I said. “I always assume they don’t see me. Saves a lot of nasty surprises.”

But not all nasty surprises. How are we to defend against this? Honk at all oncoming left-turners? Could help. Wear bright clothing? Yield right of way wherever practical? Wave? The lesson of Betty’s Toyota is that there’s no foolproof formula. But the following approach could eliminate a lot of surprises: When you face the left turner, besides slowing down, attempt to attract his attention and elicit some sort of response, like a wave or a nod. If Betty still comes across the median to nail you after a cheerful little wave, it’s no longer an accident; it’s assault with a deadly weapon.EI