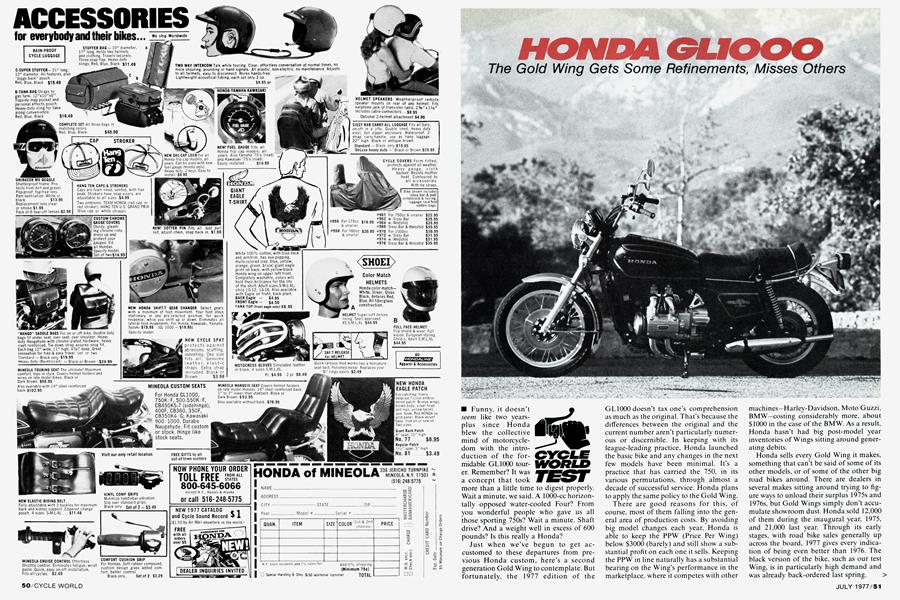

HONDA GL1000

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Gold Wing Gets Some Refinements, Misses Others

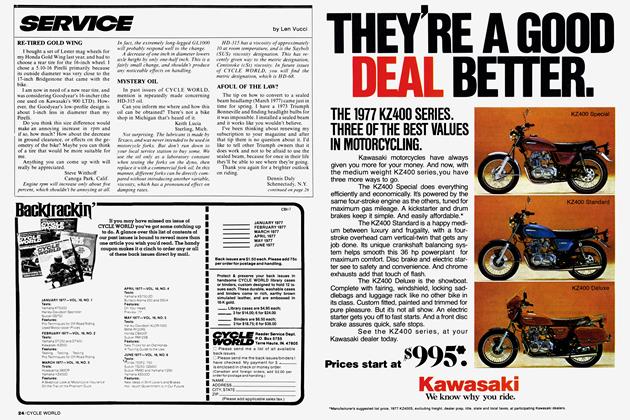

Funny, it doesn’t seem like two years-plus since Honda blew the collective mind of motorcycledom with the introduction of the formidable GL1000 tourer. Remember? It was a concept that took more than a little time to digest properly. Wait a minute, we said. A 1000-cc horizontally opposed water-cooled Four? From you wonderful people who gave us all those sporting 750s? Wait a minute. Shaft drive? And a weight well in excess of 600 pounds? Is this really a Honda?

Just when we’ve begun to get accustomed to these departures from previous Honda custom, here’s a second generation Gold Wing to contemplate. But fortunately, the 1977 edition of the GL1000 doesn’t tax one’s comprehension as much as the original. That’s because the differences between the original and the current number aren’t particularly numerous or discernible. In keeping with its league-leading practice, Honda launched the basic bike and any changes in the next few models have been minimal. It’s a practice that has carried the 750, in its various permutations, through almost a decade of successful service. Honda plans to apply the same policy to the Gold Wing.

There are good reasons for this, of course, most of them falling into the general area of production costs. By avoiding big model changes each year, Honda is able to keep the PPW (Price Per Wing) below $3000 (barely) and still show a substantial profit on each one it sells. Keeping the PPW in line naturally has a substantial bearing on the Wing’s performance in the marketplace, where it competes with other machines—Harley-Davidson, Moto Guzzi, BMW—costing considerably more, about $1000 in the case of the BMW. As a result, Honda hasn’t had big post-model year inventories of Wings sitting around generating debits.

Honda sells every Gold Wing it makes, something that can’t be said of some of its other models, or of some of the other big road bikes around. There are dealers in several makes sitting around trying to figure ways to unload their surplus 1975s and 1976s, but Gold Wings simply don’t accumulate showroom dust. Honda sold 12,000 of them during the inaugural year, 1975, and 21,000 last year. Through its early stages, with road bike sales generally up across the board, 1977 gives every indication of being even better than 1976. The black version of the bike, such as our test Wing, is in particularly high demand and was already back-ordered last spring. >

With the Gold Wing thus solidly established in the marketplace, Honda could readily get by w ithout changing a bolt or a stripe, a fact that serves to lend a somew hat different perspective to the differences between the current Gold Wing and its 1975— '76 ancestors. These distinctions may be subtle, but they are nevertheless there. Honda is trying.

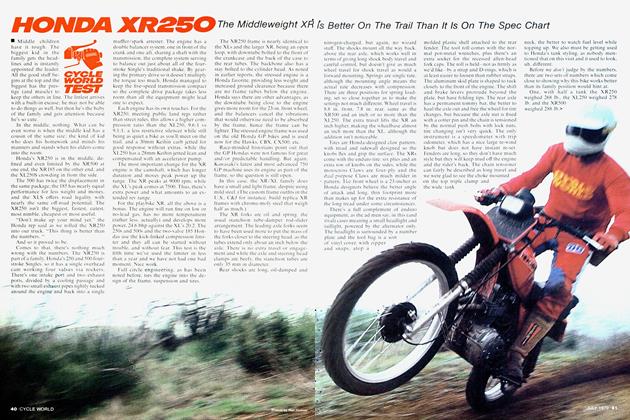

The most visible diff érence between this Gold Wing and the original—besides the snappy black paint job—is a new7 set of touring handlebars. They're 67 mm — about 2!/2 in..—higher than the old ones, affording a more upright riding position in the grand touring tradition. Naturally, this change is going to get mixed review's, just as it did among CW staff members. Riders who see all motorcycles as two-wheeled dive-bombers won’t like the higher bars simply because they’re that much further removed from the cafe look. But for riders whose idea of fun is a weekend run from L.A. to Vancouver and back, these bars will be popular. The riding position seems well calculated to prevent arm and back fatigue, and the width of the bars makes for easy steering in all situations. Oddly enough, the more upright riding position doesn't seem to be at the expense of increased wind resistance. At 60 mph it seemed easier to cut through the air on our Gold Wing than on some other large street and touring machines. We have no windtunnel-backed research to account for this, but the consensus theory is that the radiator affects the bike’s aerodynamics favorably, from the rider’s point of view. This point may be academic, though, since most Gold Wings seem to show up on the street wearing fairings.

A particularly welcome touch in connection with the new bars is new' grips. Honda has abandoned the old plastic waffle-type grips on the 1977 Wing, replacing them with softer rubber ones that are infinitely more comfortable to use. It boggles the mind: Imagine buying a new Honda and not having to immediately replace the grips.

Atop the bars, the rear view mirrors have been re-angled from 125 degrees to 137.

The new two-position saddle is about the only other change that immediately catches the eye on the new Wing, and like the new handlebars draws mixed review at best. The change from the original seat seems to be purely for cosmetic purposes, and staff riders were unanimous in their dislike for the restricted riding position the new seat affords. There is simply no comfortable way of sitting any further back on the seat than Honda seems to think you should sit. and there w'ere also complaints that the forward part of the seat slopes down generating a feeling of sliding forward. Seat materials are well chosen for extended touring, and the relationship between seat and the bike’s various controls works well for most riders, but the twoplane seat design is irritating and a definite backward step in our opinion.

HONDA

GL1000

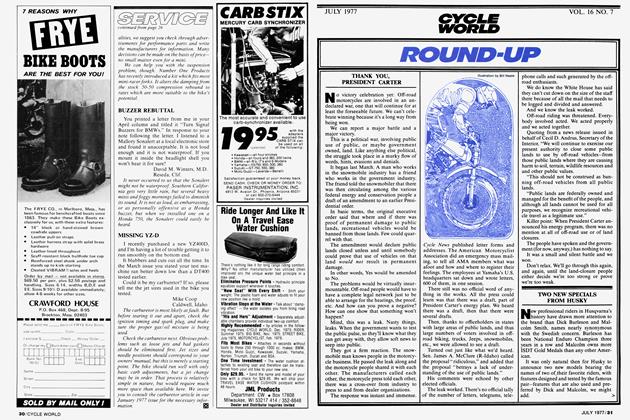

$2938

Description: Showa fork, HD 315 oil Fork travel, in.: 5.7 Engagement, in.: 5.7 Spring rate, lb./in.: 47/66 Compression damping force, lb.: 8 Rebound damping force, lb.: 26 Static seal friction, lb.: 36

Remarks: The fork on the GL is not up to par with the rest of the bike. While having an FEP impregnated top bearing for reduced friction, the fit and design of the lower portion of the stanchion tube causes it to bind in the slider under side loading. Compounding the problem is a seal with unusually high static friction. Replacing the seals with aftermarket items and switching to S&W 35/65 springs will reduce harshness.

Description: Showa shock, gas/oil mix, non-rebuildable Shock travel, in.: 3.7 Wheel travel, in.: 3.8 Spring rate, lb./in.: 100 Compression damping force, lb.: 3 Rebound damping force, lb.: 116 Remarks: Solo touring riders should find the stock shocks acceptable. When riding two-up and/or loaded, the stock springs are inadequate, even when preloaded to their maximum. Heavier springs such as S&W 100/140 dualrates would help. Even better would be a pair of their Air Adjustable shocks, enabling the rider to adjust pressure to suit load. Additionally, slightly heavier damping rates would improve handling.

Tests performed at Number One Products

There have been a couple of small but thoughtful changes to the instrument panel. The speedometer has gotten a second set of numbers, expressing speed in kilometers per hour as well as mph, and the choke control, a frequently used item on this moderately cold-blooded machine, has been relocated slightly higher for easier access. There are other changes, most of them tiny licks of chrome in places that were previously painted, but all are of the hard-to-see-even-when-pointed-out variety.

If there’s been any recurring common mechanical complaint concerning the Gold Wing, it’s about the clutch, which has shown a strong tendency to pack up at the first sign of abuse. The original Gold Wing came with a three-piece cushion clutch, designed to reduce mechanical noise. In the original design only one of the clutch's two steel plates actually bore power, which resulted in a lot of interior rivet-shearing when the hammer was dropped too enthusiastically—and sometimes even under ordinary usage. Honda has redesigned the unit so that both plates carry power, and company engineers think this should help to combat the problem. However, the new arrangement is also vulnerable. as we learned about 10 runs into our acceleration testing when the clutch went away. Honda service people will tell you the Wing’s clutch simply wasn’t designed for hole shots or stoplight warfare, and if this sort of use is avoided it's a compliant, forgiving setup that’s easy to operate the first time out.

Preoccupation with noise seems to be approaching the level of obsession with the Gold Wing engineers. Even though the original bike was one of the quietest we’ve ever tested, Honda has sought to stifle mechanical noise even further by thickening the engine casings all around. The rear of the engine case and the cylinder head covers have been beefed up from 2 Vi to 4 mm, and the front part of the engine cover has gone from 2Vi to 3 mm thickness. Not much noise gets through—just a whirring and a faint turbine-like whine—and since there’s virtually no exhaust note, there are times when you’re not sure whether the Gold Wing’s heart is beating or not.

There's rarely any confusion on this score with the drive line, though, which emits a subdued but insistent howl at highway speeds. This again is one of those things made more audible because there's no exhaust noise to mask the sound and it's tolerable for that reason. In fact, the whole issue of noise is almost academic with this machine, and we only scrutinize it because the noises that do filter through are not very motorcycle-like.

The shaft drive itself is unchanged, which isn’t surprising since there was little enough reason to change. There’s more than a hint of play in the line, with resultant slop, making smooth power roll-ons and roll-offs very touchy. However, the Gold Wing shaft drive produces almost no torque reaction and is thus one of the smoothest units going, just the thing for low maintenance, long distance voyaging.

Aside from increasing noise insulation and brightening up the timing mark on the flywheel with a dab of paint, Honda hasn’t had any reason to fuss with the Gold Wing’s engine. Although this powerplant represented a considerable departure for Honda, it’s worked quite well from the beginning, producing usable power across a broad rpm range for easy cruising and extended engine life. When a Gold Wing rider is in a hurry, the one-liter Four will comply—our original test bike put up an honest 129 mph—without breathing hard. Although the high top end can be accounted for through tall gearing, the Wing also shows up well on the drag strip. When the clutch went south, quarter-mile times were progressing steadily downward toward the high 12s, and our tech editor feels such numbers are within reach—if you don’t mind investing a clutch or two in the effort. No doubt about it, the GL’s Four is a solid piece of work. Although torque and horsepower figures are typically missing from the factory specifications sheet, and are difficult to obtain on a private dyno because of the shaft drive setup, sources close to Honda engineering are talking about Gold Wing horsepower figures in the low 80s. That’s more than enough to get the job done. continued on page 102

continued from page 55

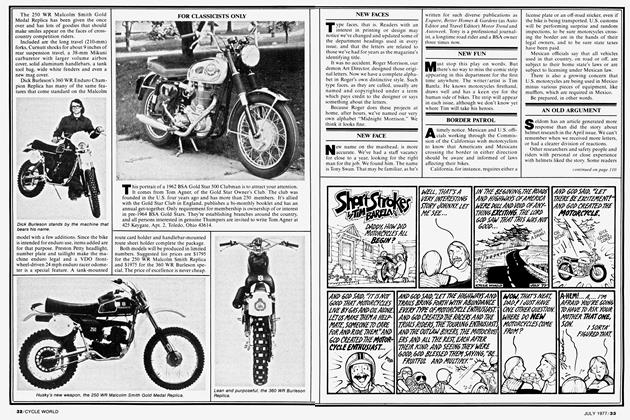

One area where the original Gold Wing drew poor marks was in suspension. Unfortunately nothing has been changed. Front end geometry is good, and damping seems to be about right, but we discovered a manufacturing shortcut on our test bike that doesn’t really square with a quality road machine such as this. The bottom ends of the fork tubes are chamfered rather than machined, leaving a hard edge that can bind inside the stanchion tube and cause scoring in the aluminum walls of same. We found considerable evidence of just this happening on our test bike, which had 4000 miles on the clock. Rear suspension is too soft, and can be bottomed without much difficulty in hard cornering, particularly with two up. Encountering a sharp bump in a hard corner means spooky control problems, although usually by the time you get to this stage you’re already scraping the pegs since cornering clearance isn’t a strong suit with this bike.

Honda has engineered itself into something of a corner with the Gold Wing’s suspension by building in limited suspension travel at both ends. This is most pronounced in the rear (3.4 in.). When you get the bike loaded up with full touring paraphernalia, as many Gold Wing riders seem to do, plus two riders, the suspension problems are magnified. A possible solution might be to install adjustable air shocks. We plan some remedial project work in this area at a later date.

For all its suspension shortcomings and general girth, though, the Gold Wing manages to somehow feel nimble in most handling situations, provided it’s not pressed too hard. The bike’s low center of gravity, augmented by the low fuel tank position, helps considerably in this feeling. So does the braking—one rear disc, two forward—which is outstanding and continues unchanged. The Gold Wing goes commendably and stops even better, with excellent control.

Styling is one of the strong points with this machine. The Gold Wing attracts favorable attention wherever it goes, particularly in its new formal black color. People are impressed by its size and by the general high quality of its overall fit and finish. If it seems rather too large and complex and car-like to motorcyclists who prefer machines they can tweak and twiddle and fix in the privacy of their own garages, it suggests coast-to-coast reliability and comfort to others. Accepting the Gold Wing is a matter of coming to grips with the concept rather than the motorcycle itself. If the long-haul trouble-free big bike approach to motorcycling hasaplaceinyour lifestyle priorities, this second edition of the Gold Wing may just be the bike for you. Its articulation of the concept may not be flawless, but it nevertheless measures up favorably to the best in the business. ^