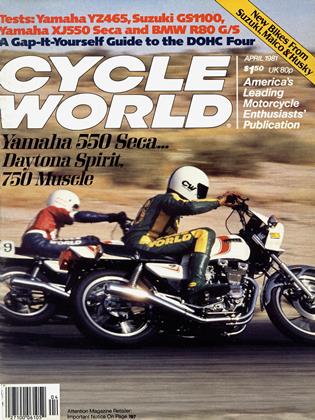

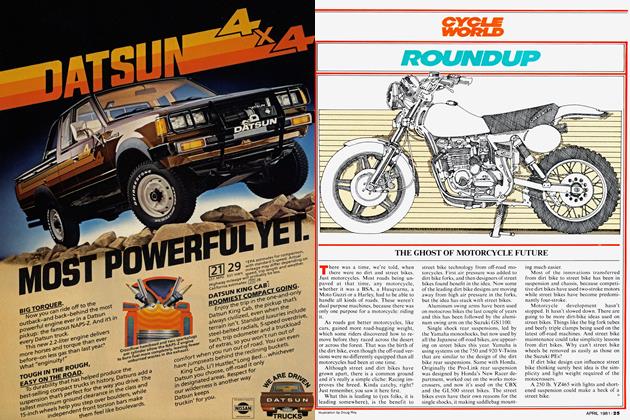

BMW R80 G/S

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Some motorcycle companies offer 50 or more models every year, with engines that are 50 to 1100cc, two-strokes and four, in a selection including mopeds, motocrossers, city scooters, sports racers and fully-equipped touring mounts.

Some motorcycle companies specialize and one of the best-known for this has been BMW. For the past generation BMW has offered what amounts to one engine in a variety of sizes and one usage, the high way. There have been some exceptions, for example the ISDT specials BMW runs once each year but in general, ever since the invention of the pure dirt bike, BMW has not offered anything that didn’t have pavement written under it.

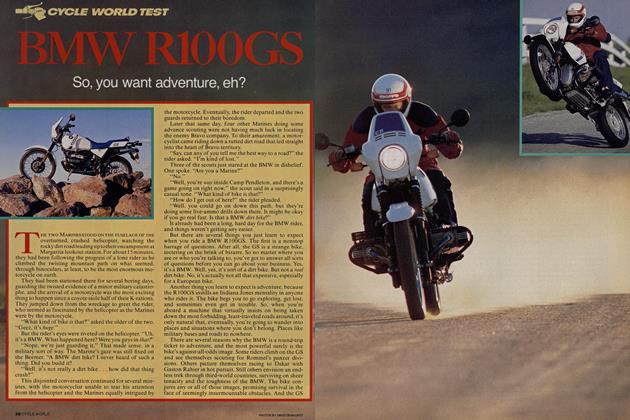

Surprise. Late in 1980 BMW introduced something different. Not quite new, as the R80 G/S (the initials stand for Woods/Street in German) uses the familiar R80 opposed Twin. Not really dirt, because those ISDT bikes are conventional racers, rather than new ideas. Not exactly dual purpose as the 80 G/S isn’t as light as the standard dual-purpose Singles and isn’t really intended for actual rock-bashing and mud-crawling.

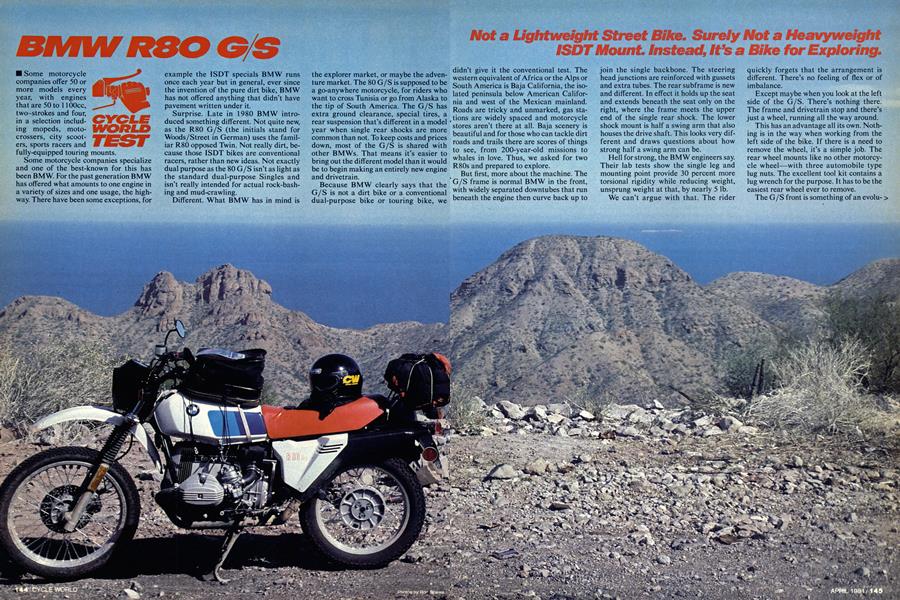

Different. What BMW has in mind is the explorer market, or maybe the adventure market. The 80 G/S is supposed to be a go-anywhere motorcycle, for riders who want to cross Tunisia or go from Alaska to the tip of South America. The G/S has extra ground clearance, special tires, a rear suspension that’s different in a model year when single rear shocks are more common than not. To keep costs and prices down, most of the G/S is shared with other BMWs. That means it’s easier to bring out the different model than it would be to begin making an entirely new engine and drivetrain.

Because BMW clearly says that the G/S is not a dirt bike or a conventional dual-purpose bike or touring bike, we didn’t give it the conventional test. The western equivalent of Africa or the Alps or South America is Baja California, the isolated peninsula below American California and west of the Mexican mainland. Roads are tricky and unmarked, gas stations are widely spaced and motorcycle stores aren’t there at all. Baja scenery is beautiful and for those who can tackle dirt roads and trails there are scores of things to see, from 200-year-old missions to whales in love. Thus, we asked for two R80s and prepared to explore.

Ron Griewe

Not a Lightweight Street Bike. Surely Not a Heavyweight ISDT Mount. Instead, It's a Bike for Exploring.

But first, more about the machine. The G/S frame is normal BMW in the front, with widely separated downtubes that run beneath the engine then curve back up to

join the single backbone. The steering head junctions are reinforced with gussets and extra tubes. The rear subframe is new and different. In effect it holds up the seat and extends beneath the seat only on the right, where the frame meets the upper end of the single rear shock. The lower shock mount is half a swing arm that also houses the drive shaft. This looks very different and draws questions about how strong half a swing arm can be.

Hell for strong, the BMW engineers say. Their lab tests show the single leg and mounting point provide 30 percent more torsional rigidity while reducing weight, unsprung weight at that, by nearly 5 lb.

We can’t argue with that. The rider

quickly forgets that the arrangement is different. There’s no feeling of flex or of imbalance.

Except maybe when you look at the left side of the G/S. There’s nothing there. The frame and drivetrain stop and there’s just a wheel, running all the way around.

This has an advantage all its own. Nothing is in the way when working from the left side of the bike. If there is a need to remove the wheel, it’s a simple job. The rear wheel mounts like no other motorcycle wheel—with three automobile type lug nuts. The excellent tool kit contains a lug wrench for the purpose. It has to be the easiest rear wheel ever to remove.

The G/S front is something of an evolution. The forks are similar to those introduced on the R65. They have more control than the forks on the larger Bimmers, which reduces the softness and excessive pitch under braking of the older models. Front wheel travel for the G/S is 8 in., nearly a dirt bike dimension. The wheel is a 21-incher, also dirt style and the tire is a new dual purpose pattern, a Metzeler design done just for this bike although it will be sold as a replacement for other brands and models. Interesting tread, with pentagonal knobs where the traditional Dunlop and Pirelli universals have square knobs. (The 18-in. rear tire has the same pattern.)

All the larger BMWs will use the new forks for 1981. Spring and damping rates, according to BMW, are unchanged for the lOOOcc BMWs using these new leading axle forks. The same sort of sharing involves engine components, such as the allaluminum cylinders. They have a high silicon content and the working surfaces of the bores are coated with nickel. Heat conductivity is three times better than before, which allows closer piston clearances. That in turn shortens break-in time and reduces oil consumption. As a bonus, the new cylinders are more than 6 lb. lighter than the old ones.

The points and coil ignition has been replaced by an electronic system, the flywheel is 8 lb. lighter and the dry, singleplate clutch is lighter and has a diaphragm spring that reduces effort at the clutch lever.

The G/S exhaust system is designed for off-road use. The headpipes roll under the cylinders, joining at the rear of the cases before they enter the left side high mounted silencer. Although the headpipes are tucked in tightly, they could use a crash guard or skid plate to protect against rocks and such.

Footpegs, shift lever and rear brake pedal are made especially for the G/S. The pegs are folding motocross designs with saw-toothed tops and strong return springs. The stamped steel shift lever pivots on the frame and connects to the transmission via linkage. It looks strange in its reversed position; the pivot in front, the shift rubber end to the rear. The brake pedal also has a saw-toothed foot surface. Neither lever folds but then it’s not as necessary on the BMW because both are somewhat protected (!) by the protruding cylinders.

Fuel tank capacity is a whopping 5.1 gal. Only one petcock is used, on the left side. It is a simple down for on, sideways for off, and up for reserve.

The 80G/S has its own orange colored seat. The base is plastic and the foam is thicker than that used on the street versions. But we’ll talk about the comfort later in the test. It’s quickly removable from the bike by simply pushing a button at the back. The button is fitted with a key lock to prevent unwanted removal and keeps thieves from the excellent tool kit that rests in a tray under the seat. A tire pump comes with each G/S and is neatly stored in the frame’s backbone tube. A nice German cold patch kit is also packed in the tool kit tray, so flats won’t pose much of a problem for the G/S rider.

Instrumentation consists of a pod that surrounds the quartz-halogen headlight and holds the speedometer, a panel of warning lights for the signals, oil pressure, neutral, alternator and high beam, and the ignition—the fork lock is separate— switch. It’s a neat enough collection, although having green for turn signals and green for neutral can be confusing. The G/S doesn’t get signal beepers, hurray. The odometer has a push-button reset which looks useful but first, the rubber cover fell off and rain water leaked inside and didn’t dry out for three days, second the push sometimes stuck on zero and needed jiggling to restart.

Because the adventure bike is intended for a variety of uses it’s offered with a long list of options. You can get different final drive ratios, a side stand—more about that later—a rear shock with reservoir, a luggage rack for the rear fender and a solo saddlebag for the right side only. The factory could only supply one bag and one rack, so the local dealer fitted our second G/S with an aftermarket rack. It was higher than the BMW item, and looked, uh, as if it had been added at the last minute, but it worked.

The saddlebag is the BMW unit sold for other models so it’s shaped to clear a shock and it goes on the right. Odd, in that if they used the left side, they could have a larger bag. But then the high-mounted muffler might get in the way. The bag will open and close without locking and snaps on and off the brackets without the key also, so it’s quick and easy. The tongue for the lock attaches to the bracket with two visible bolts: a thief would not be deterred.

With 648 mi. on one bike and 1058 mi. on the other, we packed up and headed for Baja. The plan was to head down the freeway to the Mexican border, a mere 100 mi. from our offices, get Mexican insurance, then head south to the end of available Land, a place called Cabo San Lucas. We ftgured eight to 10 days would give us time to effectively evaluate the bike in sur roundings it was designed for. Baja has nly one paved road that goes to the end of the peninsula, Mexican Hwy 1. It mean lers around, starting on the Pacific Ocean ;ide of Tijuana, then crossing the narrow

land mass about half way down, running on the Gulf of California through Santa Rosalia, Mulege and Loreto before swing ing back to the middle of the peninsula for a couple hundred miles, then turning back to the Gulf at La Paz. From La Paz it's only 140 mi. to the tip at Cabo San Lucas. Baja's paved roads are poorly paved and

poorly maintained. The original pave ment, put down five years ago, wasn't very thick. Overloaded Mexican trucks and ex treme winters have made many sections rougher than dirt roads; encountering a section of nasty chuckholes at speed is common, and of course, there's no warn ing. Also, some interesting places can be: explored by venturing down the rock and dirt roads in Baja.

Two hundred year old missions, neat little ranches nestled in green valleys and beautiful white beaches that’re completely deserted are available to the curious. Perfect for an adventure bike.

Cruising down the Interstates and maintained highways reminded us once again of just how nice a lightweight road bike and a big Twin can be. The Metzeler universals were quiet, the engine just lazed along in top gear with nothing except an authoritative low-frequency shake to remind the rider that the engine is booming out the miles. Before we began, we wondered how having one saddle bag would affect the handling. Before we reached the border we’d not only forgotten to worry, we’d forgotten the bag was there.

Shifting is much improved with the new clutch and lighter flywheel; no clunk or clank, but there is a tendency to hang up between gears. The shift throw is long and combined with the hitch in the middle of each shift, takes a little getting used to. Otherwise a neutral pops up. The shift from neutral to first feels sticky and the tranny doesn’t always go into low with the first prod. Both problems had almost disappeared by the test’s end, though.

Both brakes also take time to seat before becoming fully effective. After a couple of thousand miles both start working smoothly and need less force to operate. The front still requires more muscle than comparable Japanese discs, but not nearly as much as the older BMWs. And the unit is strong enough to slide the front tire on paved surfaces.

Twisty sections of secondary pavement are pure pleasure on the G/S. It zips in and out of corners like the lightweight street bike it is. Nothing drags or grinds itself away; cornering speeds are determined by the rider, not the bike’s exterior parts. Directional control is excellent. The GS goes where it’s pointed, no hassle or head of its own. The bike is an extension of the rider.

The handlebars are, naturally, a compromise. They fit dirt use fine; on the street they are okay at low speeds but the straight up riding position they dictate lets the wind buffet the rider at higher speeds. The blast of wind on the rider’s chest also causes arm ache and fatigue at an accelerated rate. A small quarter fairing and slightly lower bars would help the bike’s high speed comfort a bunch and wouldn’t bother the dirt use enough to matter.

Other on-road handling is normal BMW. The bike doesn’t dart around on grooved pavement and the tall top gear ratios let the engine almost idle at posted highway speeds. And engine sounds almost disappear completely; no whine, buzz or other annoyances. The rider can sit back and enjoy the scenery without distraction.

In-town riding takes a little getting used too. The abundance of torque at low engine speeds makes the shift from low to second touchy. A normal shift and clutch release will cause a leap ahead. Winding the engine in low a little and slowing the clutch release smoothes the shift. It just takes a little practice.

Keeping with the explorer theme we ventured off the pavement and up various dirt roads on the way down the peninsula. Dirt suits the G/S right down to the semiknobbies. Assuming the rider remembers it isn’t a YZ465 or an XR750, that is, assuming speeds are held down and a hazard around the next curve is expected, the G/S works quite well. Rocks make the bike’s weight felt and one never forgets those cylinders sticking ’way out. We never actually bashed one but we did have a spare rocker cover along just in case we forgot that the G/S is the world’s widest dual-purpose bike.

In sand, the G/S was not as good. Better than a road bike, but not good. The front is simply too heavy and the 3.00 section tire knifes for the bottom while the long frame and short swing arm set up a wobble.

Sliding a dirt turn with the GS is, well, different. The cylinders are right where your foot should go. Thus, the rider has to put his foot behind the cylinder, loading the bike too far to the rear. The rear loading and short swing arm cause severe sawing through the corner. Best to forget about putting your foot down in corners; the bike will saw less and better control is maintained. Putting your foot down on a bike that weighs over 400 lb. isn’t going to do much anyway, unless you’re a professional football tackle.

Suspension is pretty good for a dual purpose bike. The single shock rear works better than the front. The rear soaks up bumps and holes well until the limits of its travel are reached, then naturally bottoms, but not hard. The forks aren’t as comfortable. They transmit some shock to the rider, don’t bottom harshly, but do top anytime the front wheel leaves the ground. The topping is constant when the bike is ridden in the dirt, especially if the ground is littered with rocks. Drilling a bigger hole in the top of the damper rod would probably cure the topping; too bad the factory didn’t do it.

The orange seat that looks so comfortable is pure torture for long rides. Fifty miles at a sitting is the limit. And the second 50 gets longer. After a couple of days in the saddle, moving around constantly, trying to find a spot or position that’s comfortable takes a lot of the fun out of riding the bike. Three days into the trip, (1200 mi.), we couldn’t stand sitting on the seat any longer and decided to spend a day in La Paz. Lying in the sun and walking around town brought the feeling back to our butts. Heading back we made about 75 mi. before the ache was back. After that we vowed to stop and rest at 50 mi. intervals no matter where we were. A $4800 bike deserves a better seat—much better.

Hand controls took some getting used to. BMW has adopted the left-right turn switch, as opposed to the old up-down system and we approve of that. But on the G/S the horn button, dimmer switch and turn switch are bunched together, a good reach from the left grip. A gloved finger can’t quite fit between any two and it was all too common at first for the intended turn signal to emerge as a flash of the brights at some innocent oncomer or the car just ahead. Or the horn button doesn’t get found—you dare not look for it—until the hazard is past. The dog-legged anodized levers are fine and the grips are normal cone-shaped BMW rubber, as in some like ’em, some don’t.

The gear-drive, straight-pull throttle keeps the cable tucked out of harm’s way but the effort to work it seems a bit much for only two CV carbs. The G/S doesn’t come with the optional set-screw but the housing is tapped for it, so we had the screws installed on both test bikes. Good for highway cruising but awkward in town until you remember to back off the tension.

Oh, yeah, the stand. Every test since the invention of the boxer Twin has griped about the BMW snap-up sidestand, the one that retracts as soon as you want, if not before. So for 1981 BMW has gone to a stand that isn’t hidden when up and that locks when down.

And for the G/S, the side stand is an option. What you get standard is a center stand that hides itself when up. When lowered the stand’s outboard peg is cleverly placed exactly inboard of the left peg. The one with teeth on it. Step down and pull up in the usual way and you get the peg snapped into your shin. Only way it works is to put the sole of your right boot on the back of the stand, cock your leg behind the peg and pull, haul and pivot all in one motion. Leaning the bike against a tree is easier. We haven’t tried the optional side stand, but it’s got to be worth whatever it costs.

We were gone long enough to ride the G/S in all kinds of weather. It blows around in side winds and meeting large trucks on narrow roads is quite a thrill; it darts around like a wounded guppy. Muddy roads are handled with much better control than one would have with a pure street bike and street only tires. Wet roads pose no problem; the tires grip well on wet surfaces. Tire wear is rapid. With 3000 mi. on the bikes the rear tire was worn smooth.

Baja is a great place for road hazard surprises. Most danger spots are unmarked and roadracing into a sweeper at 80 plus can cause fear for the body. One such corner turned to pea gravel part way through, no warning of course. The G/S did some heavy duty sliding and shuddering but didn’t go down or off the road. It could have been a grim situation with road tires and a softly sprung suspension.

Gas mileage of the G/S won’t win any awards. It produced 51 mpg on our mileage loop but only averaged 35 mpg during the Baja trip. But then we rode harder while in Baja and fuel quality was marginal.

After 2400 mi. of Baja, both on and offroad, we have to rate the GS80 as a worthwhile design. It doesn’t work as well offroad as we’d like but will get the job done if ridden carefully. It’s better off-road than any other 800cc bike we can think of.

Problems were few; the leaky speedo on one bike we already talked about, the Bing carburetors on both bikes started leaking with the engine off, and one carb leaked slightly the whole trip, running or not. One bike decided it didn’t want to start in gear, requiring the rider to search for neutral before starting each time. The poor quality Mexican gas caused considerable pinging if the engines were bogged but it didn’t create a big problem. Still, a bike designed for back country use should have a little lower compression ratio so pinging wouldn’t be a problem with low octane fuel. The new aluminum cylinders have cured the oil using problems of past BMWs. Each bike covered the 2400 mi. without needing oil. Both burned less than a quarter of a quart. The new clutch makes pulling the clutch lever much easier and there’s no more clutch slip or noise when power shifting. And we didn’t burn it up at the drag strip like many past BMW clutches.

Engine performance isn’t breathtaking, in fact the bike is rather slow for an 800.^ Quarter mile times were in the high 13s with terminal speeds around 94 mph. Top speed after a half mile was 105 mph. Braking distances were a little disappointing also. The narrow rear tire slides and goes up in smoke easily during panic stops.

With the 80G/S long trips through countries with marginal or almost no roads'1 are suddenly possible. And the high speed freeways or autobahns on the way won’t intimidate the bike. Almost any trip can be made with the confidence the bike will endure. All in all, the 80 G/S is a great machine for getting away from it all. Wonder how long a trip from the tip of SouthAmerica to California would take?

BMW R80 G/S

$4800