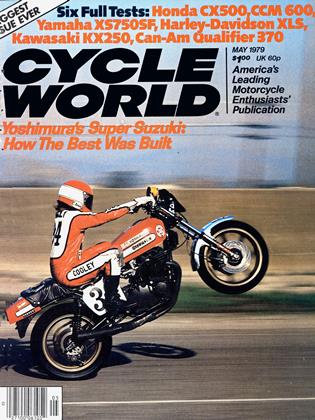

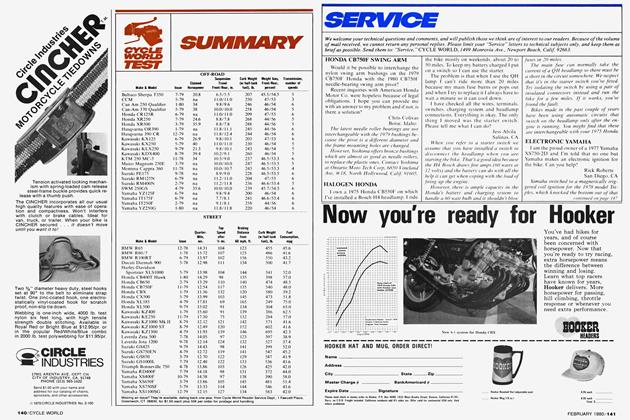

KAWASAKI KX250

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Serious Motocrosser For All Rider Levels

Kawasaki got serious last year with the introduction of the 250 and 125 KX motocrossers. They were promoted as works bikes and had no set retail price. Kawasaki hoped the dealers would spon-

sor a local motocrosser or at least partially sponsor one. The ’78 KX had some fine detailing. Many parts were drilled in an effort to offer as light a machine as possible. Like any new model the KX had a few imperfections. It had a long skinny tank instead of a short, tall one like its competitors, but its biggest flaw' was lack of w heel travel. The Kawasaki Works Replica only had 9 in. of wheel travel while the full production Honda CR250R offered almost 12 in.

With motocross development charging ahead full throttle, it becomes more and more important to try and out guess what the competition is going to produce. Figure in one year or so from finalized prototype to production machine, and the guessing game becomes serious.

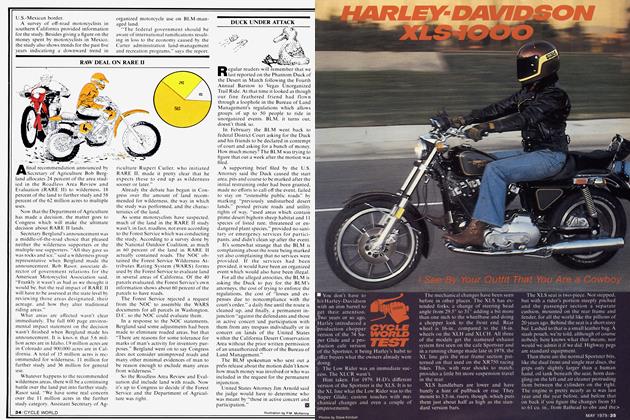

For 1979 the KX250 is right. Suspension travel has been increased by 2 in. and now measures 11 in. at both wheels. The styling has also been modernized with the use of a short fuel tank shaped like the factory racers. The green/black/gold color combination now includes green grips, fork boots and shock springs.

Almost every major part on the ’79 KX has been redesigned and most measurements have changed drastically as a result. Seat height has increased 1.5 in., ground clearance is up 1.5 in. (both due to the> increased suspension travel), footpegs are 2 in. higher (due to suspension travel and relocation), the swing arm has been stretched 2 in. and wheelbase is 1.5 in. longer. (T he wheelbase grew' only 1.5 in. because of a decrease in rake angle and a swing arm pivot relocation closer to the countershaft sprocket.)

These changes have transformed a bike that was only fair into one that is almost perfect.

The ’79 KX 250 has a single down tube frame much like last year’s w ith the head angle pulled back to 29° from 30°. It is chrome-moly steel, giving strength and light weight. A large steering head contains tapered roller bearings. The front dow ntube is large in diameter and heavily gusseted to the backbone. Additionally a smaller tube triangulates this critical area. The engine is cradled by two small pipes that start at the bottom of the front downtube. go under the engine cases and then turn up and forward, ending at the backbone. An equal size tube starts behind the swing arm pivot bolt and goes up and back to the seat rails.

The KX swing arm is a work of art. It is *made from rectangular aluminum stock, has some of the most beautiful welding we have seen, pivots in caged needle bearings and has a rubber chain protector on the drive side to protect the gold anodizing. The arm. 2 in. longer than 1978 models, allows a more severe shock angle and 4longer shocks.

Forks on the KX are terrific. Beefy 38mm stanchion tubes give strength and rigidity. The lower legs are aluminum with leading axle mounts positioned several inches above the bottom, providing plenty of engagement to prevent stickiness and binding. They are adjustable with air pressure, oil weight, oil volume and spring preload. The forks’ working parts are well

protected with rubber boots and pads, lime green naturally. The triple clamps are made from forged aluminum and have double pinch bolts and rear-set bar mounts.

KYB gas/oil shocks with progressively wound springs are standard. Shocks have large shafts and good eyes but don't offer adjustable damping and aren’t rebuildable.

Flexible color impregnated plastic is used for the fenders, FIM side number plates, and fuel tank. It is good stuff' and replacement won’t be necessary.

The new design plastic tank is shaped like last year’s Kawasaki factory motocrossers—short and high with its own distinctive shape. Fuel capacity has been increased to 2.4 gal. so 45 min. motos won't pose a problem. This shorter tank design lets the rider slide way forward in slippery or tight corners and still be on the seat.

Seat shape is changed slightly and the seat has been moved forward on the frame. It has thick foam, just the right density, and is covered with a good vinyl. The seat base is molded from nylon that is light and strong.

Wheels are strong and pleasant to look at. Rims are gold anodized D.I.D.s, conical hubs are magnesium and light, spokes are large, and the rear backing plate pivots in needle bearings as does the static arm. Tires are first class; Dunlop K190s, w hich work well on most surfaces.

Like last year, most bolts have dished heads and the larger ones have drilled shafts. Even the brake cams have drilled shafts and cams. Attention to lightness shows every place but nothing has been lightened to the point of being weak, just unecessary bulk removed.

Care has been taken to produce a light engine. The most unusual part of the design is the Electrofusion cylinder. Cylinder bores undergo a coating process whereby high carbon steel and molybdenum wires are exploded by high-voltage charges, effectively spraying the high-carbon steel and molybdenum on the cylinder walls. Six explosions of 1.15mm molybdenum wire using 16.000 volts and nine explosions of 1.6mm carbon-steel wire using 13.000 volts produce a porous Electrofusion surface approximately 0.070mm thick. The thin coating transmits heat very quickly, enabling smaller piston-to-cylinder clearances because cylinder expansion very closely follows piston expansion.

Because the surface is somewhat porous, it holds lubricating oil better than chromed bores. Kawasaki says the surface is more resistant to seizure due to lean mixtures, and, if seized, develops less scuffing. The Electrofusion cylinder is several pounds lighter than a conventional steelsleeved cylinder, easier and cheaper to produce than a chromed cylinder, but it can't be rebored.

A two-ring piston has two large holes in the intake skirt so premix enters the lower end as soon as crank pressure drops. Yamaha used a tw in hole piston similar to the KX design for several years, but recently started removing most of the intake skirt, leaving only a small edge of the intake skirt tied together with an arch. Both have advantages and disadvantages; fuel flow' is interupted by the skirt area below' the holes on the KX design but piston life is good.

Fuel flow isn’t disturbed with the YZ design but piston life is shortened. Theoretically, the arched skirt will furnish a slight pow'er advantage, but Kawasaki has chosen the design that gives the longest piston life.

An intake tract-mounted reed (with Boyensen fiber petals) controls fuel flow from the huge 38mm Mikuni carburetor. Ignition is by CDF Transmission retains five speeds, but low and second have new' ratios, both taller. Overall ratio for 1st on the '78 KX was 22.35:1, the '79 is 20.50:1. Second has been changed less; 16.38:1 in '78. 16.60:1 for'79. This change eliminates the jump between 1st and 2nd and generally makes the ratios more useable on most motocross courses. Shifting is smooth and precise—no one missed a shift or had any complaints about the shifting or ratios. Like last year, the countershaft sprocket is quite a distance from the swung arm pivot, but has excellent sealed bearing rollers above and below' the pivot to control chain tension. In addition, an aluminum chain guide with rub pads is mounted close to the rear sprocket. A good D.I.D. TR chain is also standard. The engine is solidly mounted in the frame in four places in addition to a head stay.

One kick usually brings the KX to life. The start lever is ribbed and non-slippery, and the pegs don't interfere with the lever or the operator's feet. All controls are properly placed and the bars are the right width and height for the machine.

The first 10 feet on a 1979 KX will tell an experienced rider the bike is right; balance is good, power plentiful, and there’s a solidness never felt in a Japanese MXer before. Steering is precise and the front wheel stays on the ground (hard to steer when it’s in the air) unless the rider wants> it up, then it’s easy to fly the front wheel simply by giving the bars a little tug. When up the machine doesn’t try to loop or fall over sideways, it just stays w here you want it. Thanks to the neutral handling corners may be taken high, low, on the berm or the flat. The rider chooses, not the bike.

KAWASAKI KX250

SPECIFICATIONS

DIMENSIONS

FEATURES

Power delivery is responsive and competitive, and the useable power spread is generous. Gymnastics aren't required to ride the KX either. Find a position that fits and enjoy it, the bike doesn’t care. If you like to move around on a machine, go ahead, it will w'ork well that w'ay too, and moving around is easy w ith the short tank and long seat.

Forks on the KX are the best we have experienced on a production motocrosser. They seem to be perfect on any kind of terrain. Small irregularities go unnoticed, yet they seldom bottom on large ones. Harshness is never felt in the bars and the hefty 38mm tubes don’t flex or flop around.

Rear shocks aren’t nearly as good as the forks but are usable. After the first day of riding we called them poor. They felt sticky and let the rear wheel skip across the top of high speed bumps. By the end of our second day of testing they were loosening up and starting to follow the terrain. By the end of day three they were working fine. We would guess seal friction is high until they are used for a few' days. Most people won’t replace them until they are worn out, (they aren’t rebuildable) unless a favorite brand is preferred.

The brakes on the KX are also good. Required muscle power is just right and quick chatter-free stops are normal.

The 1979 KX250 is an extremely competitive motocrosser that is easy to ride. A novice, intermediate or pro will feel comfortable on the new' KX as it is one of those rare machines that seems to meet the requirements of all rider classifications.