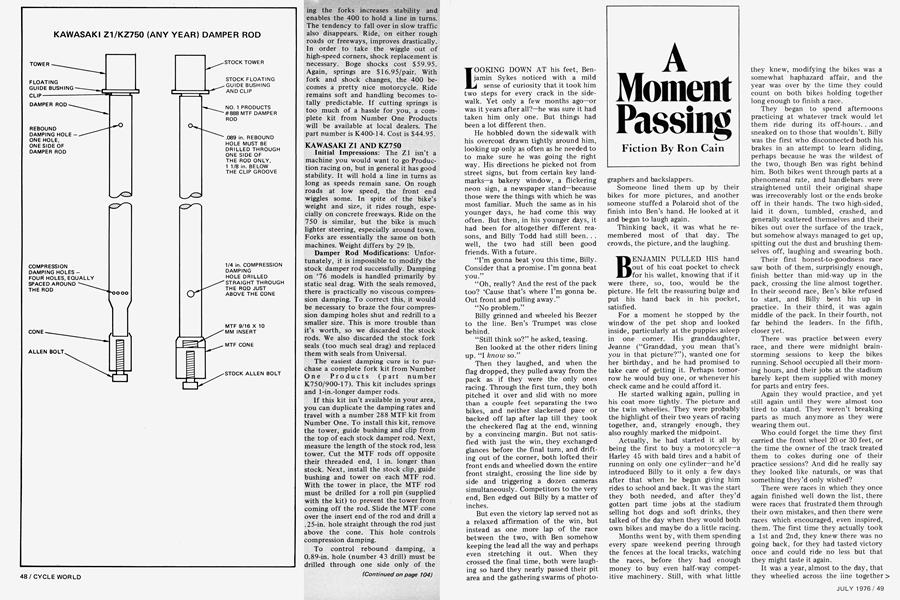

A Moment Passing

Ron Cain

LOOKING DOWN AT his feet, Benjamin Sykes noticed with a mild sense of curiosity that it took him two steps for every crack in the sidewalk. Yet only a few months ago—or was it years after all?—he was sure it had taken him only one. But things had been a lot different then.

He hobbled down the sidewalk with his overcoat drawn tightly around him, looking up only as often as he needed to to make sure he was going the right way. His directions he picked not from street signs, but from certain key landmarks—a bakery window, a flickering neon sign, a newspaper stand—because those were the things with which he was most familiar. Much the same as in his younger days, he had come this way often. But then, in his younger days, it had been for altogether different reasons, and Billy Todd had still been. . . well, the two had still been good friends. With a future.

“I’m gonna beat you this time, Billy. Consider that a promise. I’m gonna beat you.”

“Oh, really? And the rest of the pack too? ‘Cause that’s where I’m gonna be. Out front and pulling away.”

“No problem.”

Billy grinned and wheeled his Beezer to the line. Ben’s Trumpet was close behind.

“Still think so?” he asked, teasing. Ben looked at the other riders lining up. “I know so.”

Then they laughed, and when the flag dropped, they pulled away from the pack as if they were the only ones racing. Through the first turn, they both pitched it over and slid with no more than a couple feet separating the two bikes, and neither slackened pace or backed off lap after lap till they took the checkered flag at the end, winning by a convincing margin. But not satisfied with just the win, they exchanged glances before the final turn, and drifting out of the corner, both lofted their front ends and wheelied down the entire front straight, crossing the line side by side and triggering a dozen cameras simultaneously. Competitors to the very end, Ben edged out Billy by a matter of inches.

But even the victory lap served not as a relaxed affirmation of the win, but instead as one more lap of the race between the two, with Ben somehow keeping the lead all the way and perhaps even stretching it out. When they crossed the final time, both were laughing so hard they nearly passed their pit area and the gathering swarms of photo-

graphers and backslappers.

Someone lined them up by their bikes for more pictures, and another someone stuffed a Polaroid shot of the finish into Ben’s hand. He looked at it and began to laugh again.

Thinking back, it was what he remembered most of that day. The crowds, the picture, and the laughing.

BENJAMIN PULLED HIS hand

out of his coat pocket to check for his wallet, knowing that if it were there, so, too, would be the picture. He felt the reassuring bulge and put his hand back in his pocket, satisfied.

For a moment he stopped by the window of the pet shop and looked inside, particularly at the puppies asleep in one corner. His granddaughter, Jeanne (“Granddad, you mean that’s you in that picture?”), wanted one for her birthday, and he had promised to take care of getting it. Perhaps tomorrow he would buy one, or whenever his check came and he could afford it.

He started walking again, pulling in his coat more tightly. The picture and the twin wheelies. They were probably the highlight of their two years of racing together, and, strangely enough, they also roughly marked the midpoint.

Actually, he had started it all by being the first to buy a motorcycle—a Harley 45 with bald tires and a habit of running on only one cylinder—and he’d introduced Billy to it only a few days after that when he began giving him rides to school and back. It was the start they both needed, and after they’d gotten part time jobs at the stadium selling hot dogs and soft drinks, they talked of the day when they would both own bikes and maybe do a little racing.

Months went by, with them spending every spare weekend peering through the fences at the local tracks, watching the races, before they had enough money to buy even half-way competitive machinery. Still, with what little they knew, modifying the bikes was a somewhat haphazard affair, and the year was over by the time they could count on both bikes holding together long enough to finish a race.

They began to spend afternoons practicing at whatever track would let them ride during its off-hours. . .and sneaked on to those that wouldn’t. Billy was the first who disconnected both his brakes in an attempt to learn sliding, perhaps because he was the wildest of the two, though Ben was right behind him. Both bikes went through parts at a phenomenal rate, and handlebars were straightened until their original shape was irrecoverably lost or the ends broke off in their hands. The two high-sided, laid it down, tumbled, crashed, and generally scattered themselves and their bikes out over the surface of the track, but somehow always managed to get up, spitting out the dust and brushing themselves off, laughing and swearing both.

Their first honest-to-goodness race saw both of them, surprisingly enough, finish better than mid-way up in the pack, crossing the line almost together. In their second race, Ben’s bike refused to start, and Billy bent his up in practice. In their third, it was again middle of the pack. In their fourth, not far behind the leaders. In the fifth, closer yet.

There was practice between every race, and there were midnight brainstorming sessions to keep the bikes running. School occupied all their morning hours, and their jobs at the stadium barely kept them supplied with money for parts and entry fees.

Again they would practice, and yet still again until they were almost too tired to stand. They weren’t breaking parts as much anymore as they were wearing them out.

Who could forget the time they first carried the front wheel 20 or 30 feet, or the time the owner of the track treated them to cokes during one of their practice sessions? And did he really say they looked like naturals, or was that something they’d only wished?

There were races in which they once again finished well down the list, there were races that frustrated them through their own mistakes, and then there were races which encouraged, even inspired, them. The first time they actually took a 1st and 2nd, they knew there was no going back, for they had tasted victory once and could ride no less but that they might taste it again.

It was a year, almost to the day, that they wheelied across the iine together and earned themselves, perhaps by that one feat alone, a sponsorship from the motorcycle shop they had always frequented. More they could not have asked.

In time, they moved up to Juniors and knew their Expert standing could not be far off. They began to travel to more distant tracks to compete against other riders and other machines. Sometimes Ben would win, but more often Billy, for he took more chances and rode closer to the thin edge of control. Trophies began to fill their rooms to overflowing, and neither could tell you offhand just how many they had. Those who followed the circuit were aware of the newcomers, and, watching them, would usually agree that even though he rode more conservatively, Benny Sykes had the consistency and the potential to become one of the best, to challenge the small handful of riders battling for the Number One plate. Of course, only time would tell.

But along the way, something happened in Ben’s life, something new to him and different. He met Mary.

At first, she only said hello or stopped to talk for a minute between classes at school, but every once in a while, she would come down to the track to watch the races, and neither Billy nor Ben would object to her presence, for she would often sit where they could see her and cheer them on, definitely an inspiration. But when she did not come, Ben felt an emptiness inside, wishing she had, and was annoyed at Billy’s apparent indifference.

Before long, he asked her to come and watch and would pick her up at her house. His racing improved for it, and the competition between the two friends began to grow keener, more intense. The pack was no longer important, since the two were nearly always the leaders. Slides became more radical as they shut off continually later into the turns, and rarely, only rarely, did they back off the throttle when there was a chance the other might slip by.

Oddly enough though, after a while, Ben began to miss practice sessions occasionally, and was sometimes late to the races, still half-asleep and blearyeyed, becoming alert just seconds before the Bag dropped. The time came when he even missed a race entirely because, as Billy later found out, Mary’s house needed painting. And another time when her friends were taking a drive up north “and would he like to come?”

Billy was aware of the changes taking place in Ben, but said nothing, hoping, perhaps, that things might return to normal if he did not interfere.

It wasn’t long before Ben began to finish behind Billy fairly regularly. And slowly, more and more of the pack was getting past, especially on the days when Mary was absent.

Once, Billy slowed just a little, hoping to draw Ben into a private race for the lead again, but Ben, in a clumsy attempt to pass, cut him off and nearly put him into the wall. Hurt, Billy followed in dogged pursuit, got by on the inside, and never again looked back, stretching out a devastating lead.

Even those rare practice sessions that Ben did attend were changed. He always brought Mary along, and she would sit on the fence, pretending to hide her eyes from the perilous wheelies they attempted. Once again, Ben displayed the skill which had brought him this far, as he would pass Billy in a feet-up slide, showering Mary in a playful roostertail of dirt. And once again, they would laugh together. Laughter, perhaps, but somehow more refined and carefully guarded; not the same as before, neither as carefree nor as happy. Because now there were three.

On one lap, though, as Billy was drifting through the turn, feet on the pegs and sliding, he moved his weight a bit farther to the rear than normal, and for the last half of the turn actually held the front end rakishly in the air with the rear wheel still sliding. It was, without a doubt, the perfect slide, and once on the straight, he turned to catch Ben’s reaction. But either Ben mistook Billy’s glance or was trying to maintain an image to Mary. At any rate, he tried the same stunt, but lofted the front wheel too high, and though for one hopeful split-second it looked as if he might save it, the rear end swept around, and he went down. The bike landed on top of him, and together they went end over end, taking out a section of fence and hay bales. Mary screamed and ran to him. It was Billy who called the ambulance.

RECOVERY WAS SLOW and

painful, for he’d broken three ribs, his collarbone, and his leg in several places. Once or twice, Mary would push his wheelchair up to the fence at the local track, and together they’d watch Billy win his class and waggle his front wheel in the air for their benefit on the victory lap.

Ben would wave, but he and Mary would be talking of other things and would scarcely see him.

In October, with Ben just out of the wheelchair, he and Mary were wed.

Billy was the best man and tried to smile, but somehow he was awkward and could not. He and Ben joked nervously, but all talk of racing was avoided.

In November, Billy began racing as an Expert, and Ben, still recuperating, became a full-time salesman for a helmet manufacturer.

On weekends, he came out to help pit Billy’s bike and to take pictures, but he would not ride, for he could no longer afford to be injured. Billy said he understood, but talked very little, laughed hardly at all, and raced a bit more wildly.

In April, Ben sold his pickup truck, his old Harley, and his specially prepared Triumph to buy a family car. He also took a promotion that doubled his salary, provided he did some traveling. Every third week, he’d be home—that was a promise.

And for a while, he was. But gradually it became a month between visits. And then two. And three. The months lapsed into years, the years began to pile up, and he came home only a pitifully few number of times.

Benjamin stepped gingerly off the curb and crossed the street. A chilly wind kicked up, and he stuffed his hands deep into his pockets. In them were loose threads, a small hole, and little else. Quickly, out of habit, he checked for his wallet again. It was there, and he relaxed.

Strange how quickly the years had passed when he settled into a fairly changeless routine. It seemed he’d scarcely started as a salesman before he was promoted again, and yet again. He became a father almost before he knew it, needed a newer more expensive car, and gradually settled into a secure comfortable niche in life. With Mary, time was passing, and he felt satisfied, with no regrets.

IT he HAD got a BEEN call from maybe the five owner years of when the shop that had originally sponsored him. Occasionally, they worked together in business deals and still kept in touch.

“Ben? Finally. You know, I’ve had one hell of a time tracking you down.” “Carl, is that you? What’re you doing calling me in New York? Isn’t this long distance?”

“Ben, where’ve you been. I’ve been trying to get ahold of you for days now. I’ve tried every branch office your people could think of. I’ve. . . .”

“Carl, what’s wrong? You sound upset.”

“I’ve got some bad news, Ben. You remember that Bill Todd kid you used to ride with?”

“Yeah, of course. What about. . .?” (Continued on page 106) There was a pause. “He’s dead, Ben. Goin’ on two weeks now.” ,

Continued from page 51

Ben listened to the voice in the receiver and could not focus clearly on the words. Billy dead? No, that can't. . .well, I mean that's not possible. What? Dead? No, I, uh. . . .

“How did it happen?” he asked quietly, numbly detached from his own voice.

“Up in Sacramento. The Nationals. He was first into the turn and lost it. In front of the whole pack, and he lost it. Didn’t even make it to the hospital. We already had the funeral, Ben. I tried to get ahold of you, but you know how much you skip around. I tried but. . .I’m sorry.”

“Yeah, well. . .thanks, Carl. I appreciate your calling.”

“Sure thing, Ben. Just thought you’d want to know.”

“Yeah. Uh, goodbye.”

“Yeah, bye.”

Ben tried to quit his job that night, to stop this perpetual moving around, but instead got talked into settling down to a desk job back home. For weeks, he hated himself for it, but gradually he got used to it, and once again, routine slipped the years past.

When his son wanted a bicycle four years later, it took quite a lot of soul-searching, and it came with great reluctance. He encouraged him to take up baseball and football and, in time, even sky diving, but somehow motorcycles were put quietly to the side.

Eventually, his son followed him into business. His daughter grew up and went into law. And Mary, loving Mary, died of cancer. Thirteen years ago.

NOW, a parking BENJAMIN lot, through LIMPED rows across of motorcycles, and into the door of a bike shop. A display bike, a Triumph flat tracker of the early ’60s, much like the one he once owned, sat off to one side. He went to it.

At the counter, the owner was looking up a number in the parts book for a young boy and went into the back to get something. He came out a minute later with a small box, gave it to the boy, who paid for it and started to leave. Only then did the owner notice Benjamin.

“Come to buy it yet, Mr. Sykes?” “No, not yet, Charley. Maybe next week, though, when the check comes.” “Well, feel free to look around.”

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 106

“Yeah, thanks.”

He straddled the machine, and the young boy came up to him.

“You gonna buy that thing?”

“I was thinking about it.”

“What’re you going to do with it? You can’t ride it anywhere. The Ecomonitors would pick up the pollution output in minutes.”

Almost by way of comparison, he nodded toward the other bikes on the display floor. Hydrogen-oxygen powered. Exhaust emissions: water. Weighing little more than 140 pounds, and putting out better than 50 horses at little more than a whisper.

Ben looked them over, but did not seem impressed. They were too spindly looking and just didn’t feel right when he sat on them.

“I own a small track out west,” he said, mumbling. “I just might ride it there.”

The boy winked at one of the salesmen, and they both chuckled. Ben saw it but said nothing. Did they think him so old and senile that he was becoming blind and deaf? Or that he was just fantasizing?

The boy left, and Ben closed his eyes. The feel of the bike—the bars, the seat, the pegs—all pulled him back into the past. As if no time at all had passed since his racing days, he could almost feel the pulsing, throbbing roar of the engine and the flying roostertail of dirt coming from Billy off to his side. He imagined the lightness of the front end, and could feel it dangling precariously in the air as he crossed the finish line on the rear wheel, saw the bursting flashbulbs, and cast a quick glance over to Billy, his front end equally suspended. The smell of gas. The dust. The crowds and the laughter. It was all there.

But he opened his eyes, and it ruthlessly disappeared. Carefully, he took the picture out of his wallet. It was considerably yellowed, a bit torn and dog-eared, but the two laughing faces in it were still young, still fresh, still alive. He blinked, and a tear rolled off one cheek.

Slowly, almost reluctantly, he put the picture away, got off the bike with a little difficulty, and started for the door.

He had the picture, the very same picture given to him more than 50 years ago, and maybe one day soon, God willing, the bike too. But the crowds were gone, the sights and smells of racing. Billy was gone too. And perhaps most of all, so was their laughter. gj

View Full Issue

View Full Issue