Choppers

It's more like magic than machine, As if the steel, was forged in dreams, And tempered in some mystic flame Where wild incarnate spirits reign

-Jody Via

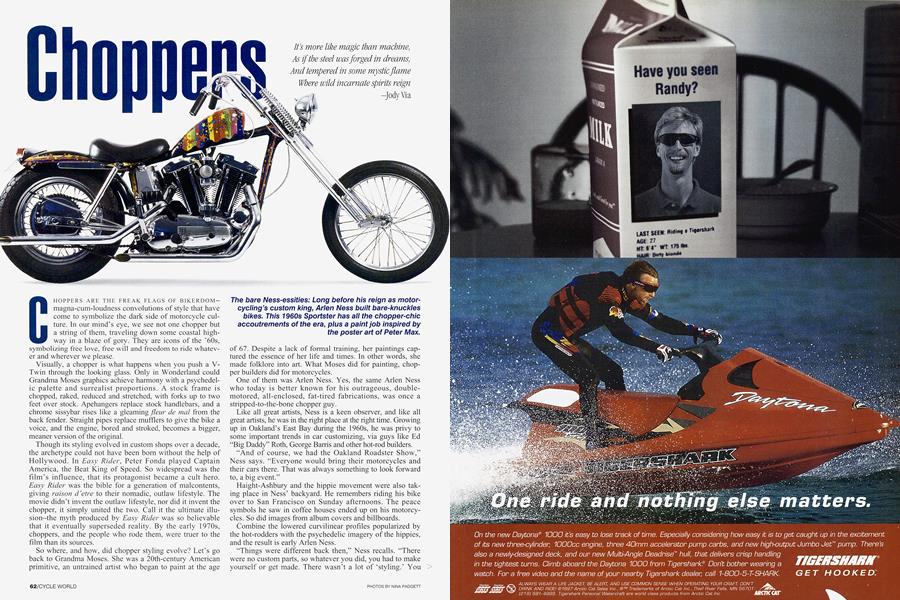

CHOPPERS ARE THE FREAK FLAGS OF BIKERDOM—magna-cum-loudness convolutions of style that have come to symbolize the dark side of motorcycle culture. In our mind's eye, we see not one chopper but a string of them, traveling down some coastal highway in a blaze of gory. They are icons of the '60s, symbolizing free love, free will and freedom to ride whatever and wherever we please.

Visually, a chopper is what happens when you push a VTwin through the looking glass. Only in Wonderland could Grandma Moses graphics achieve harmony with a psychedelic palette and surrealist proportions. A stock frame is chopped, raked, reduced and stretched, with forks up to two feet over stock. Apehangers replace stock handlebars, and a chrome sissybar rises like a gleaming fleur de mal from the back fender. Straight pipes replace mufflers to give the bike a voice, and the engine, bored and stroked, becomes a bigger, meaner version of the original.

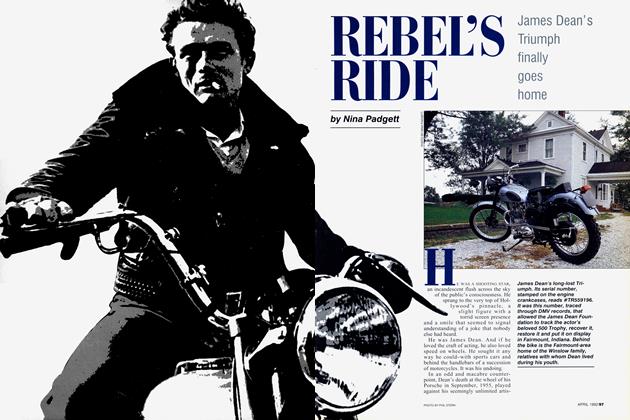

Though its styling evolved in custom shops over a decade, the archetype could not have been bom without the help of Hollywood. In Easy Rider, Peter Fonda played Captain America, the Beat King of Speed. So widespread was the film’s influence, that its protagonist became a cult hero. Easy Rider was the bible for a generation of malcontents, giving raison d’etre to their nomadic, outlaw lifestyle. The movie didn’t invent the outlaw lifestyle, nor did it invent the chopper, it simply united the two. Call it the ultimate illusion—the myth produced by Easy Rider was so believable that it eventually superseded reality. By the early 1970s, choppers, and the people who rode them, were truer to the film than its sources.

So where, and how, did chopper styling evolve? Let’s go back to Grandma Moses. She was a 20th-century American primitive, an untrained artist who began to paint at the age

of 67. Despite a lack of formal training, her paintings captured the essence of her life and times. In other words, she made folklore into art. What Moses did for painting, chopper builders did for motorcycles.

One of them was Arlen Ness. Yes, the same Arlen Ness who today is better known for his outrageous, doublemotored, all-enclosed, fat-tired fabrications, was once a stripped-to-the-bone chopper guy.

Like all great artists, Ness is a keen observer, and like all great artists, he was in the right place at the right time. Growing up in Oakland’s East Bay during the 1960s, he was privy to some important trends in car customizing, via guys like Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, George Barris and other hot-rod builders.

“And of course, we had the Oakland Roadster Show,” Ness says. “Everyone would bring their motorcycles and their cars there. That was always something to look forward to, a big event.”

Haight-Ashbury and the hippie movement were also taking place in Ness’ backyard. He remembers riding his bike over to San Francisco on Sunday afternoons. The peace symbols he saw in coffee houses ended up on his motorcycles. So did images from album covers and billboards.

Combine the lowered curvilinear profiles popularized by the hot-rodders with the psychedelic imagery of the hippies, and the result is early Arlen Ness.

“Things were different back then,” Ness recalls. “There were no custom parts, so whatever you did, you had to make yourself or get made. There wasn’t a lot of ‘styling.’ You >

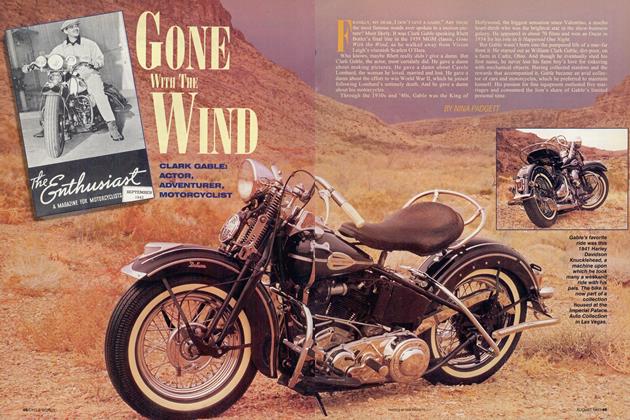

just changed the bike around so it didn’t look stock, like a hot-rod. My first bike was a ’47 Knucklehead. I probably customized the thing five times. Every year, I would take apart and redo it in a different way or a different fashion because I didn’t have the money to buy another bike.”

One of the trademarks of folk art is its regionalism. African masks are a good example; masks from different regions are marked by distinct differences in style and imagery. Early choppers were distinctly regional.

“Different areas did different things,” says Ness. “In Los Angeles, they used to put on those big, long front ends and gooseneck frames, all that stuff. Myself, I never really cared for that really out-of-proportion look. I kept the proportions more moderate-not too long a front end.”

Back in South Dakota, a teenager named Denny Berg (see “Rock & Roll,” this issue) and his friends were also building choppers, based on what they saw in the magazines, and using materials they could find on the farms where they lived.

“We only had maybe five or six months of riding time,” says Berg. “We had a lot of downtime to customize. I grew up on a ranch 50 miles from nowhere, so I just learned how to fix things and build things with what we had laying around. If you look at some of the older choppers, the headlights may be Volkswagen backup lights, spotlights off a truck or tractor, whatever was laying around. That’s what we had available and it was cheap.”

What brought chopper owners together back in the early days wasn’t lifestyle so much as love of fabrication. Building bikes and riding them was an adventure.

“Back in those days, Sturgis was the most incredible motorcycle gathering ever,” Berg recalls. “We’d look at all the bikes and ask, ‘How did you do this? What’s this part off of? What gave you that idea?’ It was a real camaraderie because it was a kind of frontier thing.”

To this day, it is the process of creative visualization, conceiving and fabricating, rather than pleasure in the finished object, that Berg is most interested in. “I find myself building a bike, finishing it, enjoying it for a very brief period of time and then it’s on to the next thing,” he says. “I’m not interested in keeping things...it’s the painting of the painting, not having the painting hanging on the wall in my home.”

As chopper style evolved through the 1960s and early ’70s, the motorcycles became less about the scattered efforts of a small group of customizers and more about the expression of a language. That language, though visual, was highly iconographie, with specific philosophical and political implications.

In Christian religious art, it is not just the imagery but its location within the church that gives it meaning. A similar hierarchy applies to chopper art. Tony Ramirez’s Knucklehead, shown on these pages, is a good example. On the tank-essentially the head of the bike-is a mural of an Indian brave and an eagle, both images central to the outlaw biker lifestyle. Not only do both images represent popular marques (Indian and Harley), they also symbolize freedom and the pioneer spirit.

The images on Ramirez’s bike don’t end with these traditional symbols. The feathers on the rear fender are more personal-they represent his three children. After almost two decades of owning and riding his chopper, Ramirez considers it a member of the family. He freely admits that he could never part with it. As such, it makes perfect sense that the decoration is partly autobiographical.

Andy Mendez, owner of the Top Dead Center bike shop in Oxnard, California, still rides the Knucklehead chopper he built 17 years ago. His rig is ripe with outlaw symbolism-swastika on the sissybar, green flames on the tank (his personal challenge to the myth about green bikes being bad luck) and 25-inch extended forks.

There is a certain amount of resentment among guys of Mendez’s generation toward the Johnny-come-lately new riders, who’ve bought into the outlaw style that riders of the ’60s and ’70s created.

“Back then, you had to pay dues,” Mendez huffs. “You saw a guy running down the road on a chop like yours; you knew you had a lot in common and you wanted to meet that guy. Everybody was like brothers. Now, things have changed; there’s no dues to pay. They buy their Harley and they get their full biker uniform.”

What hasn’t changed, though, is the chopper’s image of independence, free thinking and freewheeling. They bring out the bad guy in all of us. Be we doctors, lawyers, nurses or teachers, deep down there’s a part of each and every one of us that wants to be an outlaw.

-Nina Padgett

View Full Issue

View Full Issue