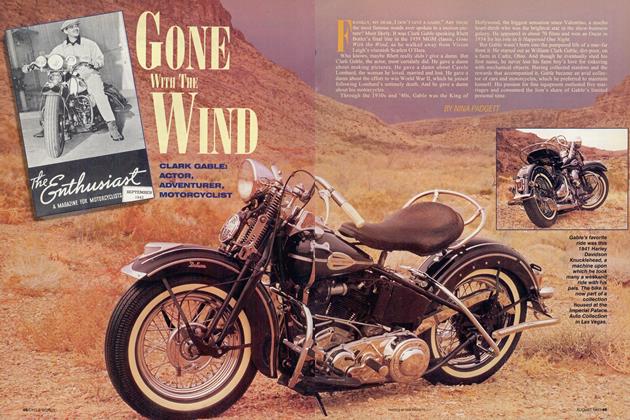

LEE M ARVI N

HOLLYWOOD'S IRON HORSE COWBOY

NINA PADGETT

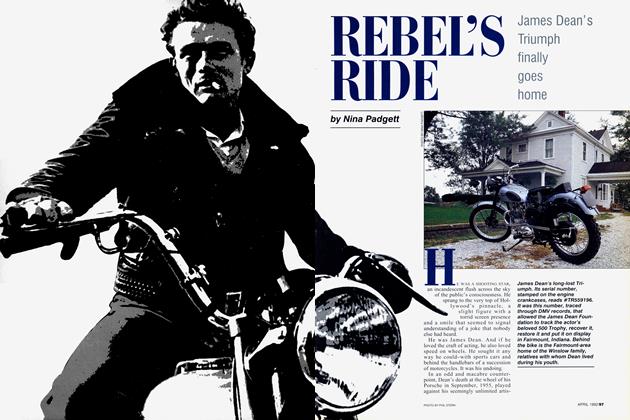

HE WAS THE ARCHETYPAL big-screen bad guy: brash and bold, with a baritone voice that became his signature. No surprise that Lee Marvin was also a rider, an image the actor cemented with his defiant performance as Chino in the infamous cinema classic, The Wild One. Rumbling onto the screen with a beat-up Panhead Harley, Marvin was the incarnation of evil-a loud, drunk, womanizing biker whose outlandish behavior quickly put him behind bars.

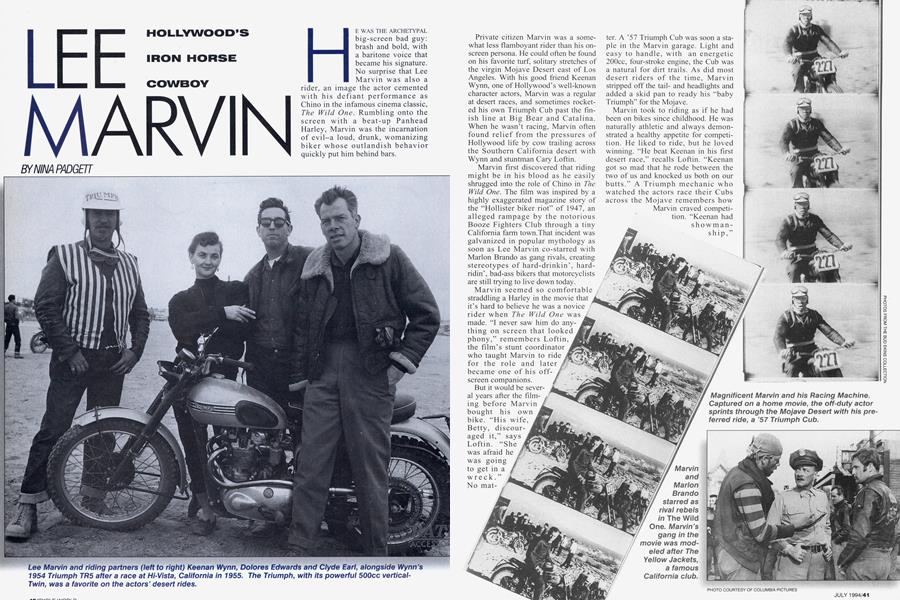

Private citizen Marvin was a some-what less flamboyant rider than his onscreen persona. He could often be found on his favorite turf, solitary stretches of the virgin Mojave Desert east of Los Angeles. With his good friend Keenan Wynn, one of Hollywood’s well-known character actors, Marvin was a regular at desert races, and sometimes rocketed his own Triumph Cub past the finish line at Big Bear and Catalina. When he wasn’t racing, Marvin often found relief from the pressures of Hollywood life by cow trailing across the Southern California desert with Wynn and stuntman Cary Loftin.

Marvin first discovered that riding might be in his blood as he easily shrugged into the role of Chino in The Wild One. The film was inspired by a highly exaggerated magazine story of the “Hollister biker riot” of 1947, an alleged rampage by the notorious Booze Fighters Club through a tiny California farm town.That incident was galvanized in popular mythology as soon as Lee Marvin co-starred with Marlon Brando as gang rivals, creating stereotypes of hard-drinkin’, hardridin’, bad-ass bikers that motorcyclists are still trying to live down today.

Marvin seemed so comfortable straddling a Harley in the movie that it’s hard to believe he was a novice rider when The Wild One was made. “I never saw him do anything on screen that looked phony,” remembers Loftin, the film’s stunt coordinator who taught Marvin to ride for the role and late became one of his offscreen companions.

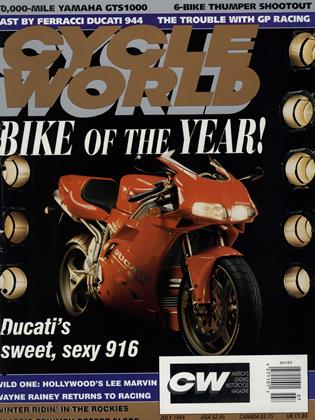

But it would be several years after the filrning before Marvin bought his own bike. “His wife, Betty, discouraged it,” says Loftin. “She was afraid he was going to get in a wreck.” No matter. A `57 Triumph Cub was soon a sta ple in the Marvin garage. Light and easy to handle, with an energetic 200cc, four-stroke engine, the Cub was a natural for dirt trails. As did most desert riders of the time, Marvin stripped off the tailand headlights and added a skid pan to ready his "baby Triumph" for the Mojave.

Marvin took to riding as if he had been on bikes since childhood. He was naturally athletic and always demonstrated a healthy appetite for competition. He liked to ride, but he loved winning. “He beat Keenan in his first desert race,” recalls Loftin. “Keenan got so mad that he rode between the two of us and knocked us both on our butts.” A Triumph mechanic who watched the actors race their Cubs across the Mojave remembers how Marvin craved competition. “Keenan had showmanship,” says Clyde Earl. “But Lee wanted to win.”

Yet Marvin never let his riding or acting success go to his head. From the start, he was “one of the guys.” Earl remembers Marvin as a private type, down-to-earth and friendly. “There were so many phonies in Hollywood at the time,” adds Earl. “Lee wasn’t like that. He talked our language, and drank beer along with everybody.”

It makes sense that Marvin chose to spend his private moments away from the Hollywood scene. He came into acting by accident, and it remained, throughout his career, a job, not a lifestyle.

After being discharged from the Marine Corps due to a spinal injury, the young Lee Marvin was working as a plumber at a theater building in Woodstock, New York, when he got his big break. Short one actor, the director eyed Marvin, who was busily fixing a toilet. The role which needed filling was that of a tall, loud-mouthed Texan. The 6-foot-2 Marvin fit the bill, and was hired.

For that role as a hard-fighting rebel, and the dozens that followed, Marvin could draw on his experience in real life. He was kicked out of a string of learning institutions, both public and private, before enlisting in the Marine Corps in 1942. Marvin went right to the front lines of World War II. His spinal injury came about during a battle in Saipan, earning him a Purple Heart.

Shortly after his debut at the theater in Woodstock, Marvin found work at the American Theater Wing in New York under the G.I. Bill. There, director Harry Hathaway spotted him and whisked him off to Hollywood for a minor role in the Gary Cooper comedy, You ’re in the Navy Now. Marvin returned to New York for several Broadway appearances, then found work with touring companies. He eventually was discovered by Hollywood agent Meyer Mishkin, who convinced Harry Cohn to sign him to a picture-topicture contract for Columbia.

Whether it was because of his imposing stature, convincing sneer or his notorious bouts of public drunkenness, Lee Marvin soon became Hollywood’s most popular heavy. He was the killer in Violent Saturday, John Wayne’s gun-running adversary in The Commancheros, one of Robert Ryan’s thugs in Bad Day at Black Rock and the ugly American in Ship of Fools. He received an Oscar for his leading role in Cat Ballou as Kid Shelleen-the nastiest (and drunkest) gun in the West.

When Marvin did play the good guy, it was within his personal, idiosyncratic frame of reference. In The Dirty Dozen, he took on the role of Major Reisman, a merciless but devoted soldier who whips 12 court-marshalled convicts into shape for a highly treacherous mission against the Nazis.

Off-screen, Marvin’s bullish, raucous behavior sometimes played havoc with his personal life. Cary Loftin recalls: “I was in a bar called The Retake one night with some friends, and Lee was loaded. I knew that he had to work the next day, so I put him in my car to take him home. I didn't know how to get to his house, and he refused to give me directions. He said, `You're the smart aleck who wants to take me home. You figure it out."

That kind of conduct didn’t sit well with his wife, and Marvin’s marriage disintegrated. Other personal problems (including a much-publicized palimony suit brought by one of his mistresses) eventually forced Marvin to give up his motorcycling hobby.

He left L.A. and took up residence in Tucson, Arizona, where he spent the last years of his life. He continued to make movies until his death, in 1987, of a heart attack.

But in theaters the world over, Marvin still lives as one of Hollywood’s best-known motorcycle rebels. “Lee used to tell me that he could go anywhere in the world and his fans would recite lines from The Wild One" says Clyde Earl. Though he played more significant roles, none seemed to capture the man behind the myth better than Chino. A rider and a rebel, Marvin remained “the wild one” long after he said good-bye to the character he made famous. □