HOW I MET THE INTERCEPTOR..

...AND LEARNED TO CHANGE MY MIND

Freddie Spencer

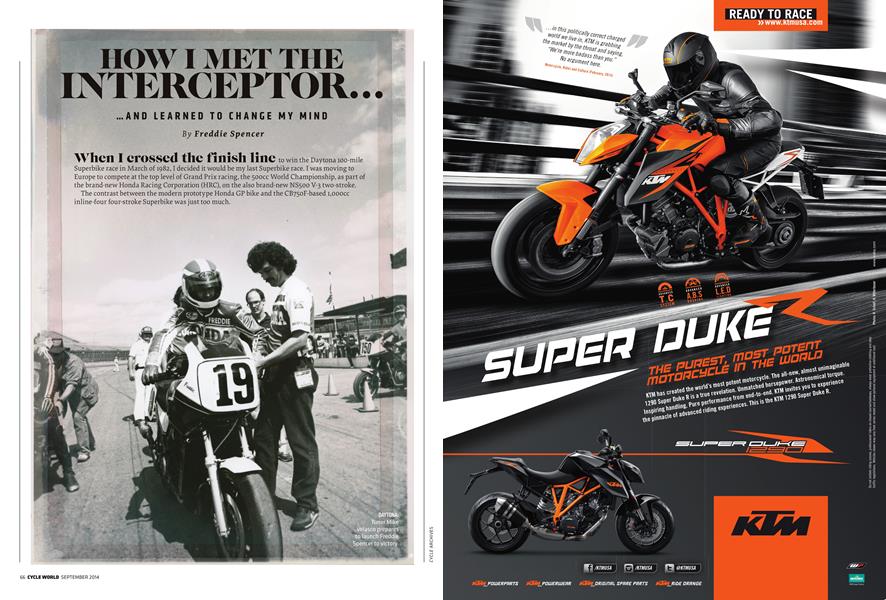

When I crossed the finish line to win the Daytona 100-mile Superbike race in March of 1982, I decided it would be my last Superbike race. I was moving to Europe to compete at the top level of Grand Prix racing, the 500cc World Championship, as part of the brand-new Honda Racing Corporation (HRC), on the also brand-new NS500 V-3 two-stroke.

The contrast between the modern prototype Honda GP bike and the CB750F-based i,ooocc inline-four four-stroke Superbike was just too much.

At that point, I was pushing myself to improve each practice, each race, each lap, and the CB750F didn’t offer me that opportunity, even if it was just one race a year at Daytona.

I had always enjoyed working around various bikes’ issues and limitations, but at that moment I had two goals: win Honda’s first soocc world championship and become the youngest-ever 500CC world champion. I needed to do it in either 1982 or 1983, and I knew that would require a higher focus. I’d need to more sharply define that balance between what I sensed and felt, between my mind-set and the practical, to integrate my pretty good human software with Honda’s best hardware as seamlessly as possible.

For the Daytona 200, my teammate Mike Baldwin and I rode Honda’s new 1000 V-4, the FWS. It was amazing. We battled with Kenny Roberts on his soocc factory GP bike, competed with him straight up. I finished second to Graeme Crosby even after I changed tires twice—one of my favorite races ever. The FWS, precursor to the Interceptor, happened because of the NR500 Grand Prix bike, the famous oval-pistoned V-4 Honda had built to make its return to Grand Prix supremacy in 1979. The NR was not successful on the track and only won two events: a rain-soaked Japanese National Championship race at Suzuka in 1981 and in a five-lap heat race at Laguna Seca that same July where I beat Kenny Roberts. It was only a five-lap heat race, but it was against the World Champion on a factory Yamaha.

When I came into the pits after that win, the NR engineers were so happy that you would have thought I won the British GP! The NR500 is a perfect example of a project that pushed the bar forward in what’s possible. It led to the FWS.

At Daytona in March 1982, the big V-4’s power delivery was amazing, perfectly complementing

THE V-4 FWS1000 WAS A HUGE STEP FORWARD IN GIVING THE RIDER MORE FREEDOM TO CONTROLTHOSE TRANSITIONS, TO ALLOW ME TO GET ON THE THROTTLE SOONER AND STILL BE ABLE TO CONTROL THE BIKE AND MANAGE WHEELSPIN.

what I’d always focused on most: the transition from the point at maximum lean angle to the critical moment of initial acceleration. The linear powerband was an evolution compared to the inline CB’s narrow powerband and brutal throttle response. That is everything! Between what you sense and feel in your right hand with the throttle and its connection to the rear tire, the V-4 FWS1000 was a huge step forward in giving the rider more freedom to control those transitions, to allow me to get on the throttle sooner and still be able to control the bike and manage wheelspin. Dual-compound tires were still in the future then. On that hot Sunday afternoon, a single-compound rear tire had to be hard enough to withstand the tremendous load of the 31-degree banking as well as the demands I would put on the left side coming out of the infield into NASCAR turn one and exiting the chicane into NASCAR turn three. And it had to last the whole 200 miles! That linear, more tractable, and efficient powerband made the difference in managing tire wear. Even though we had to change a rear tire in both fuel stops, we still almost won the race.

Back in Europe that year, we won two soocc Grand Prix races and had a good chance to win three more—but mechanical and reliability issues can and do happen in a brand-new team and bike over a long, hard season. I finished third in the 500CC World Championship in 1982.

In October, we went to Daytona to test the NS500 V-3 and the Michelins to get ready for the 200 in March. At the test, Honda had a new prototype superbike for 1983, an all-new 75OCC V-4 Superbike (AMA rules had changed from i,ooocc to 75OCC for 1983). It was a visually inspiring motorcycle; the influence of the NR and FWS was easy to see in its lines. Honda asked me to take a few laps on it to see what I thought, even though everyone was aware of my decision never to race Superbikes again. As I accelerated down pit lane the first time, I already knew for sure I would race it. Honda had built a bike to race first and be a streetbike second. I did five laps and came in; the smile on my face said it all. I told them there was nothing to improve in the chassis or suspension. It was all the things the CB750F could never be. The CB was a muscle car from the ’60s, a raw street car racer at home on your local dragstrip. And the Interceptor was a Porsche 962, at home in the 24 Hours of Le Mans. It had great stability in all areas: braking, direction change, acceleration (thanks to its NR500 smooth-powercharacter heritage). It also had a fundamental quality I would always try to instill in every bike I had a hand in developing: forgivingness.

There was just a connection that you could trust its responses and ride it to the edge and past. There was always more cornering clearance and no excess movement in that chassis and suspension. There was no need to allow extra room under braking or acceleration or exiting corners to allow the bike to gather itself up; it seemed to almost anticipate my directions. It was always predictable, a near-perfect balance of chassis, suspension, and engine that let the rider be in charge. From the oval-piston, eight-valveper-cylinder NR500 to the more conventional round-piston, four-valve-per-cylinder FWS1000, each one was an evolution and each gave the new V45 Interceptor engineers great components to work with to create something very special!

It’s a bike that taught me the value of being able to change my mind; after those five laps I was raring to go to Daytona in March. That Interceptor gave me the gift and privilege of winning the 1983 and 1984 Superbike races and the ultimate—the 1985 Daytona 200. As a matter of fact, in what were absolutely golden, blessed years for me, the Interceptor and I never lost a race together. Thanks to Honda for giving us a sportbike that was designed to race first and provided so many of us with great moments over these past 30 years.

IT HAD GREAT STABILITY IN ALL AREAS: BRAKING, DIRECTION CHANGE, ACCELERATION (THANKS TO ITS NR500 SMOOTHPOWER-CHARACTER HERITAGE). IT ALSO HAD A FUNDAMENTAL QUALITY I WOULD ALWAYS TRY TO INSTILL IN EVERY BIKE I HAD A HAND IN DEVELOPING: FORGIVINGNESS.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

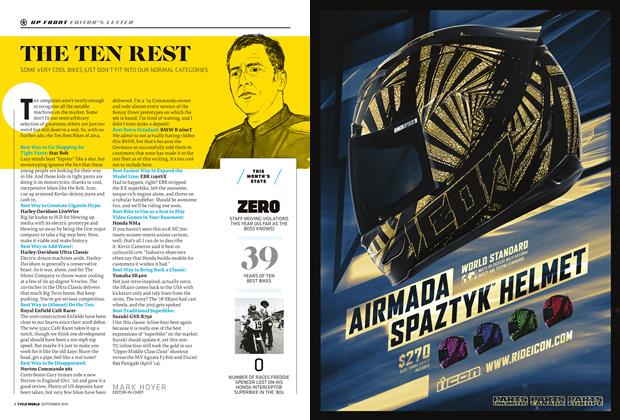

Up FrontThe Ten Rest

September 2014 By Mark Hoyer -

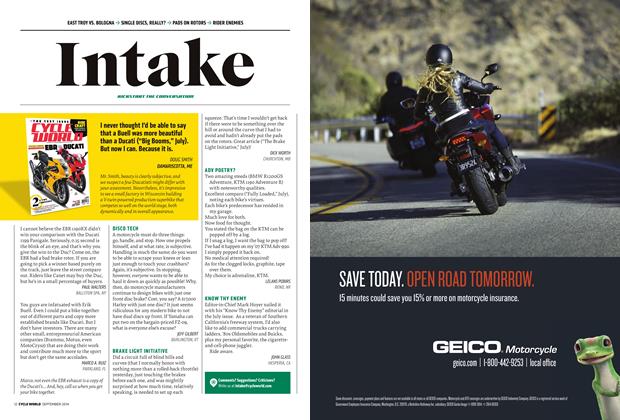

Intake

IntakeIntake

September 2014 -

Ignition

IgnitionNew Racebike, New Ball Game

September 2014 By Allan Girdler -

Ignition

IgnitionThe John Penton Story

September 2014 By Andrew Bornhop -

Ignition

IgnitionYikebike

September 2014 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago September 1989

September 2014 By BC