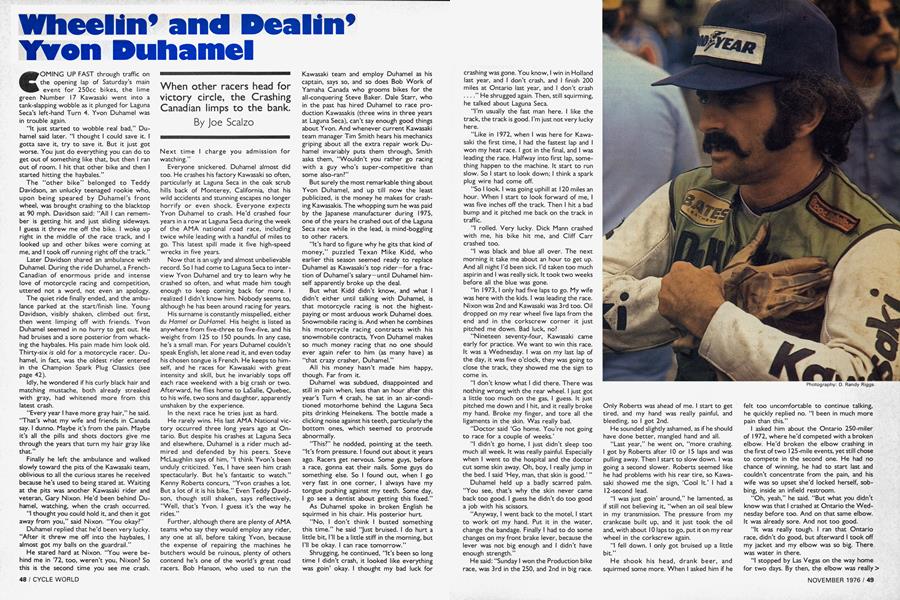

Wheelin' and Dealin' Yvon Duhamel

When other racers head for victory circle, the Crashing Canadian limps to the bank.

Joe Scalzo

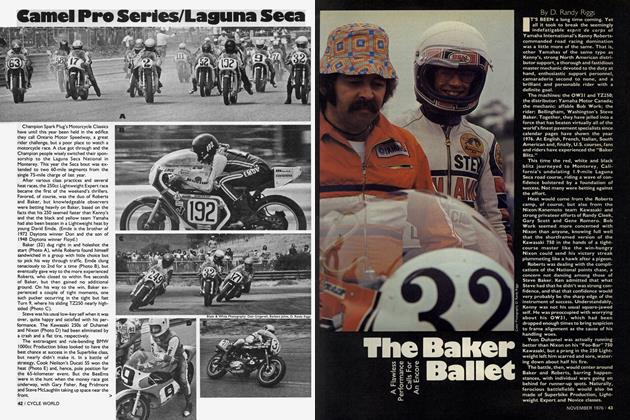

COMING UP FAST through traffic on the opening lap of Saturday's main event for 250cc bikes, the lime green Number 17 Kawasaki went into a tank-slapping wobble as it plunged for Laguna Seca's left-hand Turn 4. Yvon Duhamel was in trouble again.

“It just started to wobble real bad,” Duhamel said later. “I thought I could save it. I gotta save it, try to save it. But it just got worse. You just do everything you can do to get out of something like that, but then I ran out of room. I hit that other bike and then I started hitting the haybales.”

The “other bike” belonged to Teddy Davidson, an unlucky teenaged rookie who, upon being speared by Duhamel’s front wheel, was brought crashing to the blacktop at 90 mph. Davidson said: “All I can remember is getting hit and just sliding sideways. I guess it threw me off the bike. I woke up right in the middle of the race track, and I looked up and other bikes were coming at me, and I took off running right off the track.” Later Davidson shared an ambulance with Duhamel. During the ride Duhamel, a FrenchCanadian of enormous pride and intense love of motorcycle racing and competition, uttered not a word, not even an apology.

The quiet ride finally ended, and the ambulance parked at the start/finish line. Young Davidson, visibly shaken, climbed out first, then went limping off with friends. Yvon Duhamel seemed in no hurry to get out. He had bruises and a sore posterior from whacking the haybales. His pain made him look old. Thirty-six is old for a motorcycle racer. Duhamel, in fact, was the oldest rider entered in the Champion Spark Plug Classics (see page 42).

Idly, he wondered if his curly black hair and matching mustache, both already streaked with gray, had whitened more from this latest crash.

“Every year I have more gray hair,” he said. “That’s what my wife and friends in Canada say. I dunno. Maybe it’s from the pain. Maybe it’s all the pills and shots doctors give me through the years that turn my hair gray like that.”

Finally he left the ambulance and walked slowly toward the pits of the Kawasaki team, oblivious to all the curious stares he received because he’s used to being stared at. Waiting at the pits was another Kawasaki rider and veteran, Gary Nixon. He’d been behind Duhamel, watching, when the crash occurred.

“I thought you could hold it, and then it got away from you,” said Nixon. “You okay?” Duhamel replied that he’d been very lucky. “After it threw me off into the haybales, I almost got my balls on the guardrail.”

He stared hard at Nixon. “You were behind me in ’72, too, weren’t you, Nixon? So this is the second time you see me crash. Next time I charge you admission for watching.”

Everyone snickered. Duhamel almost did too. He crashes his factory Kawasaki so often, particularly at Laguna Seca in the oak scrub hills back of Monterey, California, that his wild accidents and stunning escapes no longer horrify or even shock. Everyone expects Yvon Duhamel to crash. He’d crashed four years in a row at Laguna Seca during the week of the AMA national road race, including twice while leading with a handful of miles to go. This latest spill made it five high-speed wrecks in five years.

Now that is an ugly and almost unbelievable record. So I had come to Laguna Seca to interview Yvon Duhamel and try to learn why he crashed so often, and what made him tough enough to keep coming back for more. I realized I didn’t know him. Nobody seems to, although he has been around racing for years.

His surname is constantly misspelled, either du Hamel or DuHamel. His height is listed as anywhere from five-three to five-five, and his weight from 125 to 150 pounds. In any case, he’s a small man. For years Duhamel cöuldn’t speak English, let alone read it, and even today his chosen tongue is French. He keeps to himself, and he races for Kawasaki with great intensity and skill, but he invariably tops off each race weekend with a big crash or two. Afterward, he flies home to LaSalle, Quebec, to his wife, two sons and daughter, apparently unshaken by the experience.

In the next race he tries just as hard.

He rarely wins. His last AMA National victory occurred three long years ago at Ontario. But despite his crashes at Laguna Seca and elsewhere, Duhamel is a rider much admired and defended by his peers. Steve McLaughlin says of him, “I think Yvon’s been unduly criticized. Yes, I have seen him crash spectacularly. But he’s fantastic to watch.” Kenny Roberts concurs, “Yvon crashes a lot. But a lot of it is his bike.” Even Teddy Davidson, though still shaken, says reflectively, “Well, that’s Yvon. I guess it’s the way he rides.”

Further, although there are plenty of AMA teams who say they would employ any rider, any one at all, before taking Yvon, because the expense of repairing the machines he butchers would be ruinous, plenty of others contend he’s one of the world’s great road racers. Bob Hanson, who used to run the Kawasaki team and employ Duhamel as his captain, says so, and so does Bob Work of Yamaha Canada who grooms bikes for the all-conquering Steve Baker. Dale Starr, who in the past has hired Duhamel to race production Kawasakis (three wins in three years at Laguna Seca), can’t say enough good things about Yvon. And whenever current Kawasaki team manager Tim Smith hears his mechanics griping about all the extra repair work Duhamel invariably puts them through, Smith asks them, “Wouldn’t you rather go racing with a guy who’s super-competitive than some also-ran?”

But surely the most remarkable thing about Yvon Duhamel, and up till now the least publicized, is the money he makes for crashing Kawasakis. The whopping sum he was paid by the Japanese manufacturer during 1975, one of the years he crashed out of the Laguna Seca race while in the lead, is mind-boggling to other racers.

“It’s hard to figure why he gits that kind of money,” puzzled Texan Mike Kidd, who earlier this season seemed ready to replace Duhamel as Kawasaki’s top rider—for a fraction of Duhamel’s salary—until Duhamel himself apparently broke up the deal.

But what Kidd didn’t know, and what I didn’t either until talking with Duhamel, is that motorcycle racing is not the highestpaying or most arduous work Duhamel does. Snowmobile racing is. And when he combines his motorcycle racing contracts with his snowmobile contracts, Yvon Duhamel makes so much money racing that no one should ever again refer to him (as many have) as “that crazy crasher, Duhamel.”

All his money hasn’t made him happy, though. Far from it.

Duhamel was subdued, disappointed and still in pain when, less than an hour after this year’s Turn 4 crash, he sat in an air-conditioned motorhome behind the Laguna Seca pits drinking Heinekens. The bottle made a clicking noise against his teeth, particularly the bottom ones, which seemed to protrude abnormally.

“This?” he nodded, pointing at the teeth. “It’s from pressure. I found out about it years ago. Racers get nervous. Some guys, before a race, gonna eat their nails. Some guys do something else. So I found out, when I go very fast in one corner, I always have my tongue pushing against my teeth. Some day, I go see a dentist about getting this fixed.”

As Duhamel spoke in broken English he squirmed in his chair. His posterior hurt.

“No, I don’t think I busted something this time.” he said “Just bruised. I do hurt a little bit, I’ll be a little stiff in the morning, but I’ll be okay. I can race tomorrow.”

Shrugging, he continued, “It’s been so long time I didn’t crash, it looked like everything was goin’ okay. I thought my bad luck for crashing was gone. You know, I win in Holland last year, and I don’t crash, and I finish 200 miles at Ontario last year, and I don’t crash

----” He shrugged again. Then, still squirming, he talked about Laguna Seca.

“I’m usually the fast man here. I like the track, the track is good. I’m just not very lucky here.

“Like in 1972, when I was here for Kawasaki the first time, I had the fastest lap and I won my heat race. I got in the final, and I was leading the race. Halfway into first lap, something happen to the machine. It start to run slow. So I start to look down; I think a spark plug wire had come off.

“So I look. I was going uphill at 120 miles an hour. When I start to look forward of me, I was five inches off the track. Then I hit a bad bump and it pitched me back on the track in traffic.

“I rolled. Very lucky. Dick Mann crashed with me, his bike hit me, and Cliff Carr crashed too.

“I was black and blue all over. The next morning it take me about an hour to get up. And all night I’d been sick. I’d taken too much aspirin and I was really sick. It took two weeks before all the blue was gone.

“In 1973,1 only had five laps to go. My wife was here with the kids. I was leading the race. Nixon was 2nd and Kawasaki was 3rd too. Oil dropped on my rear wheel five laps from the end and in the corkscrew corner it just pitched me down. Bad luck, no?

“Nineteen seventy-four, Kawasaki came early for practice. We want to win this race. It was a Wednesday. I was on my last lap of the day, it was five o’clock, they was going to close the track, they showed me the sign to come in.

“I don’t know what I did there. There was nothing wrong with the rear wheel. I just got a little too much on the gas, I guess. It just pitched me down and I hit, and it really broke my hand. Broke my finger, and tore all the ligaments in the skin. Was really bad.

“Doctor said ‘Go home. You’re not going to race for a couple of weeks.’

“I didn’t go home, I just didn’t sleep too much all week. It was really painful. Especially when I went to the hospital and the doctor cut some skin away. Oh, boy, I really jump in the bed. I said ‘Hey, man, that skin is good.’ ”

Duhamel held up a badly scarred palm. “You see, that’s why the skin never came back too good. I guess he didn’t do too good a job with his scissors.

“Anyway, I went back to the motel, I start to work on my hand. Put it in the water, change the bandage. Finally I had to do some changes on my front brake lever, because the lever was not big enough and I didn’t have enough strength.”

He said: “Sunday I won the Production bike race, was 3rd in the 250, and 2nd in big race. Only Roberts was ahead of me. I start to get tired, and my hand was really painful, and bleeding, so I got 2nd.

He sounded slightly ashamed, as if he should have done better, mangled hand and all.

“Last year,” he went on, “more crashing. I got by Roberts after 10 or 15 laps and was pulling away. Then I start to slow down. I was going a second slower. Roberts seemed like he had problems with his rear tire, so Kawasaki showed me the sign, ‘Cool It.’ I had a 12-second lead.

“I was just goin’ around,” he lamented, as if still not believing it, “when an oil seal blew in my transmission. The pressure from my crankcase built up, and it just took the oil and, with about 10 laps to go, put it on my rear wheel in the corkscrew again.

“I fell down. I only got bruised up a little bit.”

He shook his head, drank beer, and squirmed some more. When I asked him if he felt too uncomfortable to continue talking, he quickly replied no. “I been in much more pain than this.”

I asked him about the Ontario 250-miler of 1972, where he’d competed with a broken elbow. He’d broken the elbow crashing in the first of two 125-mile events, yet still chose to compete in the second one. He had no chance of winning, he had to start last and couldn’t concentrate from the pain, and his wife was so upset she’d locked herself, sobbing, inside an infield restroom.

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “But what you didn’t know was that I crashed at Ontario the Wednesday before too. And on that same elbow. It was already sore. And not too good.

“It was really tough. I ran that Ontario race, didn’t do good, but afterward I took off my jacket and my elbow was so big. There was water in there.

“I stopped by Las Vegas on the way home for two days. By then, the elbow was really big. I went home to the hospital and a guy looked at it and said, ‘I think it’s broke. It’s got lots of water in there. Going to have to take it out.’

“But the next day I gotta be in Toronto, do a one-hour TV show. I took the plane and went there. I was with Johnny Weismuller, the swimmer. We did the TV show together.

“Next day I went back to the hospital and the doctor looked at the elbow and said, ‘Yeah, it’s broke.’ So he took a needle and took out all the water and put me in a cast. ‘You can’t go and race for at least a month,’ he said. ‘It’s a bad break. Lotta chopped bone and all.’

“That was a Friday. On Saturday I wanted to go out. I couldn’t get a jacket on with the cast. So I took the cast off. Me and my wife went to a restaurant for dinner. Came back on Monday to see the doctor. He looked at it, he said, ‘What happened? Your elbow is gonna get bad, I think there’s still more blood in there.’

“ ‘Just take the blood out and build me a new cast,’ I said. ‘I’ll keep it for two weeks.’

“Ah,” Duhamel went on, smiling, “that’s not so bad. I know more than doctors.” Then he told how he’d raced against doctor’s orders at this year’s Daytona.

“Around Christmas, I’d broken my knee racing snowmobiles. They had to operate. Forty days in a cast. One week before Daytona in March, I took off the cast.

“The doctor had said: ‘I don’t want to see you race before June.’

“So I went and raced at Daytona for Kawasaki. They had to pad the saddle with sponge rubber, then help me on and off the bike, because my knee wouldn’t bend enough. I think I could have run in the top five but the exhaust pipe broke, and the chain started coming off.

“Later I raced at Imola and got 17th. At Paul Richard in France, I got 3rd. Then it was time to come back to see the doctor who’d told me not to race till June.

“ ‘Your knee is still pretty bad,’ he said. ‘You’re not going to be able to play football or hockey or anything like that. Take it easy on it. By June, a couple more months, you’ll be ready to race.’

“Lucky thing for me that doctor don’t read the papers too much, and see that I been racing all over the world. I think he’d really be mad, if he’d known.”

Continuing, Duhamel said, “I’m small, but I do lots of weight-lifting when I was younger. I think my bones are pretty big; my muscles are strong.

“People know me in Canada when I sign for something. I work hard. I tried racing cars and do okay. Snowmobiles, I once won the World Championships at Eagle River with a broken knee. One year I finished 2nd in the standings a week after breaking my back. I still hold the world record of 127 miles an hour. I won the Winnipeg—St. Paul 600-mile race. I don’t think nobody accomplished in snowmobiles, cars and motorcycles what; I have. I race all kinds of motorcycles when I was younger. I did lots of dirt track, speedway, short track, motocross, ice racing—if I’d been a little more lucky, and found a sponsor when I was 20 years old, I think I could probably get Number One in the States.”

He talked about his early motorcycle racing, the hard times. “I was a little French Canadian. I spoke no English. To get to the races I had to travel all night. I was working at my brother’s garage. I worked from six in the morning until 12 at night.

“Saturday nights I closed the garage, jumped in my car —I had the motorcycle in the back seat —and drive to Reading or York, Pennsylvania. Got there six, seven in the morning. Get the bike out, put on the wheels and handlebars. Practice, race, win, crash —all kind of stuff happen to me.

“Get up next morning at six o’clock, take a shower, drive back to Quebec, open the garage. I did that for many, many years and I missed only one dirt track race in all that time. That was in 1964. And that was because of a street accident. I crashed on the street, and they took 40 stitches in my head. I also break my shoulder and foot. This accident happen on a Friday and the race was on a Monday. There was no way they’d let me race. They want me to stay three weeks in the hospital.

“But I came out of the hospital the next Wednesday. On Sunday I raced at a road race in Canada and won two classes, the 250 and 500. I had to put a handkerchief on my head because I had no more hair, it was all shaved. The stitches were really tender. And I had to wear a brace on my shoulder because my shoulder really hurt when I hit bumps. It was a rough track.

“I had many disappointments with motorcycles. Many many times I be leading, and someone fall down in front of me. All kinda things like that.”

His best moments were when he raced for the Canadian Yamaha importers and had Bob Work as his mechanic. From 1968 through 1970 they enjoyed outstanding success on the AMA tour. Yvon Duhamel wasn’t thought of as a crasher then. But in late 1970 Kawasaki came to him (or he went to Kawasaki) and he was offered a fantastic sum if he’d road race its untested team bikes. Yamaha couldn’t match the offer; no other factory could. Duhamel simply couldn’t say no to that much money, not after all the earlier years of struggle. So he left Yamaha and Bob Work. His new Kawasaki contract forbad Duhamel from doing any dirt track racing, presumably because he might hurt himself and miss road races. Curiously, the restrictive contract allowed him to continue the dangerous snowmobile competition.

Duhamel has been under contract to Kawasaki ever since ... six disappointing, crash-filled years with a total of only five major U.S. victories, but lucrative seasons for all of that.

“How much did Kawasaki actually pay you last year?” I asked.

Duhamel looked at me. He hesitated before answering.

“My manager and I negotiate with Kawasaki in California. And with the Japanese. We talk with Kawasaki’s top men from Japan, from Canada and from the States. Even sometimes from England and France. That’s where you get all that money, little bit here, little bit there.

“Last year Kawasaki paid me $90,000.”

Ignoring the expression of disbelief on my face, he continued: “But that’s not all. Plus my contract with Boge shocks and a magazine in France, I make another $90,000. That’s, what, that’s $180,000.

“But I never count. Because I make money from snowmobiles too. I was making almost $100,000 with snowmobiles. My contract was for seventy thou, plus all my prize money and other contracts.

“I got other businesses. I have a motel at home that with the Olympics it’s pretty busy now. I have a decal business, patches and T -shirts.

“I suppose, last year, all told, I make about $3 15,000.”

I asked him to repeat the incredible figure, just to be certain I’d heard him correctly.

“You must have a very good manager.”

“Oh, yes. The best. Jerry Tremllan. He does ice hockey players too. He does golf players. We’re partners in hotel management. This October 17th we’re opening a motorcycle store.”

Seventeen, Duhamel explained, is a special number to him.

“I been racing 17 years, I been married 17 years, and my bike is number 17. Everything comes up 17.”

“But there’ve been more than 17 crashes,”

I said.

“Oh, yeah. Many more.”

“Doesn’t that stuff bother you?” I asked. “Everyone saying you’re a crasher and all?”

“No,” he said quickly. “You see, when I race with Yamaha I never crash too often. You ask Bob Work. I crash a few times, not many.

“But with Kawasaki, I would say that with 95 percent of crashes, I crash because something happen to my machine.

“Maybe it’s slower than the others, so I have to go faster. I want to win. When you have speed, you get in a corner, you wanta make up time, you gotta just brake a little bit farther down. And you get on the gas a little sooner, take more chances, get sideways.

“Many times I’ve seen Roberts and Baker go sideways, so bad, on Yamaha. At Laguna Seca last year, and the year before. At many race tracks. Those guys make a mistake, they pitch their bikes sideways, the thing goes sideways and makes big black tire marks on the pavement. But they don’t crash.

(Continued on page 59)

Continued from page 50

“Me, I move six inches, I’m down. Like I told that to (Jim) Evans last year when he joined Kawasaki. I told him, Take it easy. Kawasaki’s not a Yamaha. When it starts to go sideways. . . .’”

Evans, after two serious Kawasaki crashes, is now retired from racing.

“The way the Kawasaki frame is made,” Duhamel said, “or the way the engine is placed, something is wrong there. It just wants to lose traction at the rear wheel. It moves six inches and that’s it, it wants to highside you.”

Duhamel, I realized, would never be so candid with a reporter unless something were seriously amiss between himself and Kawasaki. Something was amiss. This year is to be Duhamel’s last with Kawasaki. It may be his last racing season, too, but he seemed relieved to talk about it.

“Tell you the truth, right now I don’t like racing as much as I used to. I used to race for nothing, used to spend my pay and my wife’s pay to go racing. And I was really crazy about racing. Taat’s all I could see. But the last three years, I ;;tart to slow down. I start to think more. A août what could happen.

“But what really put me out of racing is that late last year Kawasaki told me they’re not going road racing anymore.

“I don’t like the way they told me. I was always doing my best for them. Always. I was trying to win races even when I don’t feel like it because I was in pain. But they just say to go away.

“I must know maybe 50 people at Kawasaki. Japanese, American, Canadian. But not one of those people come up and told me. It was somebody else that I never saw in my life. Just came and told me ‘We’re not going racing anymore.’ Without any explanation.

“So I said, ‘Well, that’s funny.’ I think at least one of the big bosses from Kawasaki would tell me, ‘Yvon, let’s go out for food,

I have bad news for you.’

“Jerry, my manager, couldn’t believe it when Kawasaki said they were not going to race. He turned white. Luckily I had a twoyear contract or I wouldn’t be racing this year. Or today. Because Kawasaki said we’re not going racing, and that’s it. I said ‘What about my contract?’ They said, ‘Your contract is up.’ I said, ‘No, I got another year.’ They said, ‘Well, it’s no good anymore.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’

“So I finally had my lawyer look at it. And the contract was really made good. And because it was made good, Kawasaki had to go back racing, but I had to accept less money.”

I asked Duhamel if it were true that Kawasaki had offered Mike Kidd a dirt track and road racing deal, apparently planning to make Kidd Duhamel’s successor.

Duhamel said he knew nothing about it. “All I know,” Duhamel said, “is that it’s not right to turn a guy out cold after he’s been five years with a company. I think I been a very good worker for Kawasaki. We don’t win all the races, but we try. They didn’t even offer me another job or anything. They said, This is it. Goodbye.’ No, it’s not right.”

He mumbled something about having no solid plans for 1977, but if he did race again he hoped it would be for Bob Work and Yamaha Canada, teamed with Steve Baker. “My butt’s starting to throb,” he said next, ending the interview abruptly.

Duhamel was never a threat in the following day’s Champion Classic, his posterior continuing to ache, but he still refused to surrender positions gracefully. He only finished 7th overall, but he did finish. That night he flew home to Quebec. American fans wouldn’t see him again until October 3rd at Riverside, California, his and Kawasaki’s swan song.

Later I asked Bob Work about Duhamel. Work said he would love to have Duhamel back on a Yamaha. Steve Baker would be his number one rider, Duhamel his number two, and they would be the world’s outstanding road race team. But Work worried that Yamaha Canada couldn’t afford Duhamel, whose reported asking price is $150,000.

I asked Bob Hanson, who used to run the Kawasaki race team, about Duhamel. He said Yvon was a great rider. Like Duhamel, he faulted the machines Yvon was given to race. If the Kawasaki road racers didn’t lack speed, they lacked handling. Even when the bikes were faster than anything on the track they experienced ruinous fuel economy, guzzling so much gas they needed extra, timeconsuming pit stops. Except for 1973, when Kawasaki dominated, the bikes were either too new and untested or too old and slow. In six years Duhamel rarely started a road race National on level footing with the other teams. He was always handicapped in some way. He always had to ride harder, take more chances than anyone else if he was to win. Winning was what he was being paid all that money for. And so he crashed a lot trying.

“I want to prove that I’m good, and that when I race, I race to win,” Duhamel once said. “I race because I want to do a good job.” “You could have won more races if you’d stayed with Bob Work,” I said.

“Yeah. But then I’d had to win about every race in the world to make half the money Kawasaki pays me now.”

“So it’s the money that’s become important, more than winning?”

“The money is in there, sure. Especially when I’m 36 years old. I mean, I’m not 17 anymore. Only my number is.”

And that, basically, is the sad thing about Yvon Duhamel.

Where would he be today if, six years ago, he hadn’t changed teams and, in effect, swapped victories for cash? Less wealthy, certainly. Yet happier, less battered and by now possibly the greatest road racer in the world instead of the richest.

He did go after the big buck. Who, in Yvon Duhamel’s place, wouldn’t have done exactly the same thing?