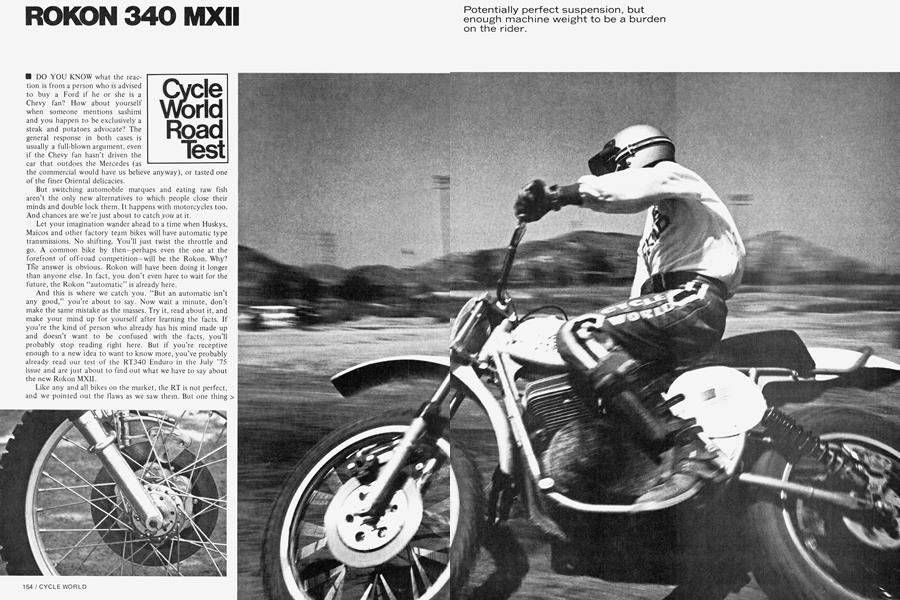

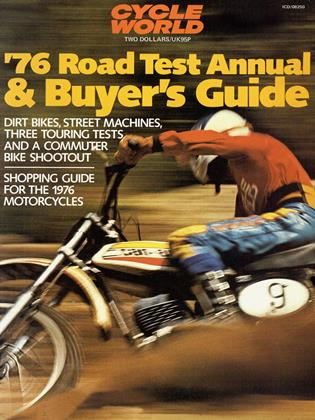

ROKON 340 MXII

Cycle World Road Test

■ DO YOU KNOW what the reaction is from a person who is advised to buy a Ford if he or she is a Chevy fan? How about yourself when someone mentions sashimi and you happen to be exclusively a steak and potatoes advocate? The general response in both cases is usually a full-blown argument, even if the Chevy fan hasn’t driven the car that outdoes the Mercedes (as the commercial would have us believe anyway), or tasted one of the finer Oriental delicacies.

But switching automobile marques and eating raw fish aren’t the only new alternatives to which people close their minds and double lock them. It happens with motorcycles too. And chances are we’re just about to catch you at it.

Let your imagination wander ahead to a time when Huskys, Maicos and other factory team bikes will have automatic type transmissions. No shifting. You’ll just twist the throttle and go. A common bike by then—perhaps even the one at the forefront of off-road competition—will be the Rokon. Why? The answer is obvious. Rokon will have been doing it longer than anyone else. In fact, you don’t even have to wait for the future, the Rokon “automatic” is already here.

And this is where we catch you. “But an automatic isn’t any good,” you’re about to say. Now wait a minute, don’t make the same mistake as the masses. Try it, read about it, and make your mind up for yourself after learning the facts. If you’re the kind of person who already has his mind made up and doesn’t want to be confused with the facts, you’ll probably stop reading right here. But if you’re receptive enough to a new idea to want to know more, you’ve probably already read our test of the RT340 Enduro in the July ’75 issue and are just about to find out what we have to say about the new Rokon MXII.

Like any and all bikes on the market, the RT is not perfect, and we pointed out the Raws as we saw them. But one thing that truly impressed us was the Salsbury torque converter that smoothly transmits the horsepower at the crank to the rear wheel. In our estimation it is a method of future drive that can be had now.

The Rokon MXII is a much improved version of the American-built automatic. Notice the word built rather than manufactured. Rokon uses bits and pieces from suppliers outside the U.S., as well as certain components from this country. The engine is produced in Germany by Sachs, the forks come from Betor in Spain, the variable ratio torque converter is made by an American company, as are the brakes. All of this paraphernalia is then shipped to Keene, New Hampshire, where it is assembled for sale.

Designed with one purpose in mind, motocrossing, the MXII is far superior to the enduro version in all respects. The most noticeable improvements are in the chassis. It doesn’t take a sharp eye to see the liberal use of gussets at possible stress areas. Frame tubes are joined together with quality in mind, not quantity. Each and every weld offers good penetration and a smooth, good looking joint. The frame is finished in a metallic silver-gray. We have used our steam cleaner on the bike several times and have not had the paint flake off as is the case with some bikes.

In addition to the gussets, the frame also differs from the RT in weight distribution and steering geometry, which makes it turn faster and steer more precisely. The bike is suspended at both ends with what are theoretically the ideal forks and shocks. As we found out on the track, however, that isn’t quite the case. A quick trip to the Number One Products shock dyno reaffirmed our suspicions after the track test.

With the early Betor forks chances were pretty good that after several hundred miles seals would be worn out and start passing oil. It appears that, in an effort to avert this problem, subsequent fork units use modified seals. This was necessary, but it poses more problems than it solved. Actual measured seal friction is 20 lb., which is too much. In comparison, most bikes average about 10 lb. when new; this decreases to about five after a break-in period.

So, this is what we have. When the wheel moves across ripples and braking bumps, not enough force is generated to work the forks, so all of the shock is taken up by the rider’s forearms. In an effort to correct this, light springs (at least for the weight of the bike), are used with a very thin oil, perhaps ATF. This almost makes ripples bearable, but what happens over the larger bumps?

The damper rod has been designed for a heavier weight oil, something in the neighborhood of 20 or 30 weight. When a large bump is encountered, the oil flows freely through the damping passages; at the same time the springs, which are light to begin with, offer little resistance to compression, and the forks bottom out.

This oversight can be rectified by removing the seals and throwing them as far as possible. Replace them with any one of the many accessory pieces available. Also dump the watery liquid that is passed off as damping oil, refill the forks with a heavier weight oil and fit 25or 27-lb. springs. The ratio of compression to rebound damping will remain the same, which is good, but the seal friction will not be an adverse aspect any longer.

As for the rear end, things work great. Red Wing gas/oil shocks now come as standard equipment on the MXII. We were given a pair of these for a product evaluation several months ago and fitted them to a Husky modified to the Mikkola Replica specifications (cantilevered). Results were positive. We found the same to be true with the Rokon. After long periods on the track, we did not notice any decrease in the damping rate. For the weights of our test riders the springs were adequate; however, it was necessary to run with the preload in the highest notch. The only recommendation we can make regarding that is to fit heavier springs that allow more latitude of adjustment.

One advantage of the gas/oil shocks is their capability of being mounted upside-down. This reduces unsprung weight. But because of the type of mounts on the Rokon, this method of mounting is impossible; there just isn’t enough clearance.

Common methods of preventing tire spin while braking or accelerating include using rim locks or screws. Rokon uses neither. Instead, the Sun rims utilized are made with “tits” inside that bite into the bead area of the tire. This method aids in fast tire changes. The front axle does not screw into either fork leg, but is retained only by pinch bolts on each leg.

Kelsey-Hays manufactures the brake components found on the Rokon. Another first for this American bike is the disc brakes used on both wheels. The front caliper is mounted to an arm attached to the fork leg. The caliper is allowed to float and self-center when the brake is applied.

Some people will say that the master cylinder is in a vulnerable place on the handlebars. This may be the case if one has a habit of tipping over, but if the two wheels stay under bike and rider where they belong, then things are fine. The master cylinder is made by the same manufacturer that provides them for Honda.

One thing we must caution Rokon owners about is routing of the brake hose. We had a problem with the front hose working its way around the fork leg and rubbing against the tire. Before long there was a hole in the hose and no brake. After picking up another hose, installing and securely attaching it to the fork leg (this time for sure), we had no further troubles.

Because of hydraulic leverage, it is possible to cut an inch or so off the brake lever to protect it somewhat from possible crash damage. There is still plenty of room to get two fingers on the lever, and that, afterall, is all that’s needed.

After several hours of hard riding the rear brake became difficult to use. It was like a switch, on or off, and required a maximum of effort to operate. The trouble was quickly traced to the stationary puck that was no longer content to stay put. Actually, the screw that holds it in place with the caliper backed out, allowing the puck to rotate and finally wedge between the caliper and disc. By disassembling the caliper, using a locking liquid on the screw threads, and putting the brake back together, the problem was solved.

The basic engine layout and pieces of the MXII are similar to those used in the enduro version. The power plant is a single-cylinder, air-cooled two-stroke. In an effort to reduce friction and heat and improve performance, the piston is fitted with only one ring. In addition to the conventional intake, transfer and exhaust ports, there is a boost port just above the intake. As the piston reaches BDC, a group of holes in the piston open this port and the last bit of fresh gas is forced from the lower end to the combustion chamber.

We asked Rokon to furnish us with a bike equipped with a cylinder ported to its hop-up specifications. This involves raising the exhaust port, opening up the intake to match the optional 44mm carb and cutting the intake skirt of the piston. A different exhaust is also available as an option.

PARTS PRICING

A deficit of 175cc is a lot to be giving away against 500-class competition. The standard 340 will run with the 360 Bultaco Frontera but wouldn’t stand a chance against a full race bike in that class. Why not sell the MX with the trick porting? The answer has to do with the number of parts that must be inventoried. At this stage of the game, only one cylinder must be kept in stock instead of two.

The trick port job is necessary if the MXII is going to be pitted against the “big boys” on the track. And if the optional pipe and carburetor are going to be used, prepare yourself for laying out another $140 in addition to the port job that will cost at least $30. That isn’t all; yet another area must be modified before all that horsepower can be used: the torque converter.

The torque converter is the odd-looking set of pulleys attached to the left side of the power plant. Here is how it works. The drive and driven pulleys are connected by means of a toothed belt. From idle speed up to 2749 rpm the drive pulley spins on the end of the crankshaft while the belt remains loose. At 1750 rpm the outside ramp of the drive pulley moves in toward the engine, and at the same time begins to spin the belt. The belt turns the driven pulley. As the speed is increased, the diameter of the driving pulley increases, which, in terms of effect, is like changing from a 14 to a 15-tooth countershaft sprocket, and so on.

Before the hop-up kit can be used, the converter rollers and springs must be replaced with stronger ones. This costs approximately another $20. These parts increase the engagement speed by 1000 rpm.

The casting that fits next to the cylinder on the right side of the engine has been removed on the race version. This cover housed the regulator and the wiring connections for the lights on the enduro bike. It has now been machined off and the resulting hole covered by a flat piece of aluminum.

With the casting removed, the starter housing has been rotated 90 degrees, thus keeping the starter handle out of the way of the rider’s knee as he slides forward on the seat. At best the starting procedure is awkward, more so than before. To start, stand on the right side of the bike holding the throttle and brake lever with the left hand. Pull the starter rope with the right hand while holding the throttle open slightly. Perhaps the one redeeming factor is that one or two pulls of the starter rope are all that it takes to start the engine.

On the opposite side of the starter housing is the flywheel magneto that furnishes spark to the engine. The cover is installed with a bead of silicone rubber to seal the ignition parts from moisture.

Seating is high to accommodate the 8 in. of travel at the rear end. Once in motion, we didn’t notice the height. Standard rubber is by Carlisle, a 3.00-21 in front and a 4.00-18 in the rear. A 4.00 seems small for a 500-class bike but it’s perhaps the widest 4.00 around. The actual width is greater than that of most 4.50s. Following the MX is like being behind a 450 Maico; it can really throw the dirt and rocks.

Frequent checks for loose spokes proved a waste of our time. We were surprised to note that they didn’t need retightening once. The rigidity of the Sun rims is somewhere between that of the shoulderless Akronts and D.I.D.s.

Power characteristics of the engine are a little deceiving at first, attributable to an ever-so-slight lag in the torque converter before it couples up with the engine. Once we got the hang of it, power could and had to be applied sooner than on a conventional bike when coming out of a corner. And come out it will. During the course of our test, we encountered many different track conditions . . . everything from drenched to parched. That 4.00 tire gets hold of the ground and slingshots the MX into the next corner.

ROKON 340 MXII

$1745

SUSPENSION DYNO TEST

Remarks: Damping in this Betor fork is unusual in that seal friction is inordinately high, and thus dampens considerably more than the viscous forces that are usually the prime damping factor. The result is that the forks bind over small bumps and bottom over large ones. The solution is to install a freer seal (such as a universal) and an oil with more viscosity than the ATF originally used. This should both free the forks from binding and restore proper viscous damping.

Remarks: The rear wheel on this bike has an average mechanical advantage on the shock of 2.3:1. To work properly, a shock mounted with a mechanical advantage this high must have higher damping forces than a conventionally mounted unit. In the Rokon application, the Red Wing shock characteristics are excellent, and ride is comparable to that of a G.P. Maico with the advantage of two additional inches of travel. For riders over 160 lb., however, we recommend a heavier spring.

Tests performed at Number One Products

The so-called best line happened to be anywhere we were on the track. With improved steering geometry and weight distribution, any line could be changed at will without fear of having the front end wash out. Steering is similar to that of a Maico; the Rokon is precise and can be steered around any corner or bounced off a berm with the back sliding sideways.

Jumping and crossing up in the air can be done with relative ease, even though the bike weighs in at a hefty 256 lb.

Improving the forks will make the Rokon a perfect bike to ride in short MX races, but after 30 or 45 minutes its weight will tire even the toughest. On the other hand, this bike would make an ideal desert sled. Its ease of operation and plush suspension lend themselves well to the wide-open spaces. Even as an enduro bike the weight isn’t out of the ball park.

Now that you’ve listened to our test impressions, the next step is to take your own test ride before you make up your mind about “automatic” motorcycling. And by the way, at dinner tonight . . . don’t order the steak and potatoes again. ÊÖ

View Full Issue

View Full Issue