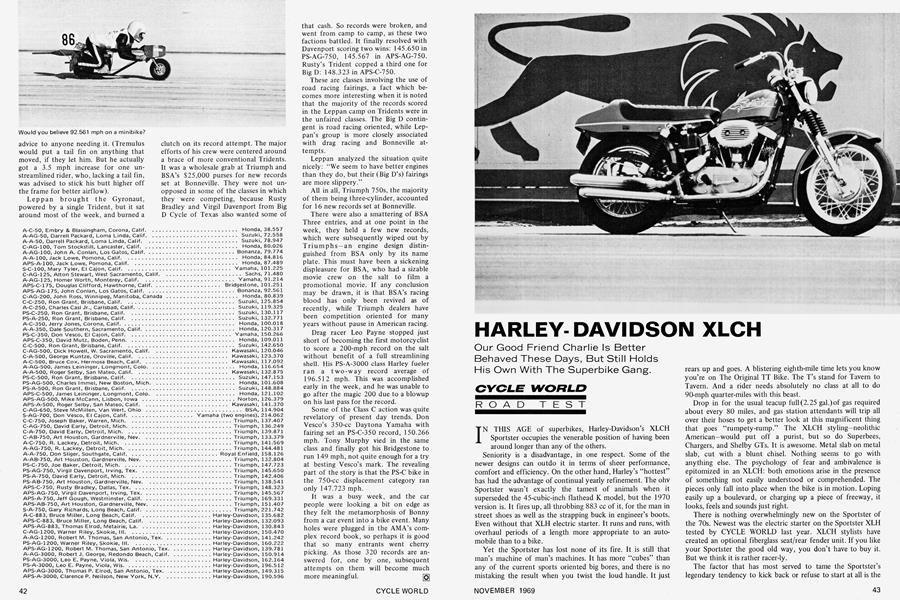

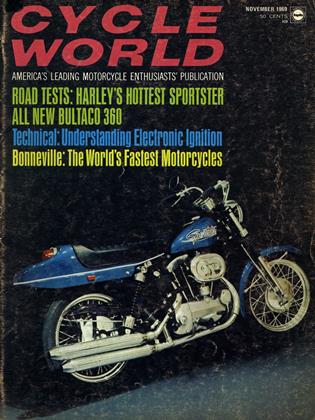

HARLEY-DAVIDSON XLCH

Our Good Friend Charlie Is Better Behaved These Days, But Still Holds His Own With The Superbike Gang.

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

IN THIS AGE of superbikes, Harley-Davidson’s XLCH Sportster occupies the venerable position of having been around longer than any of the others.

Seniority is a disadvantage, in one respect. Some of the newer designs can outdo it in terms of sheer performance, comfort and efficiency. On the other hand, Harley’s “hottest” has had the advantage of continual yearly refinement. The ohv Sportster wasn’t exactly the tamest of animals when it superseded the 45-cubic-inch flathead K model, but the 1970 version is. It fires up, all throbbing 883 cc of it, for the man in street shoes as well as the strapping buck in engineer’s boots. Even without that XLH electric starter. It runs and runs, with overhaul periods of a length more appropriate to an automobile than to a bike.

Yet the Sportster has lost none of its fire. It is still that man’s machine of man’s machines. It has more “cubes” than any of the current sports oriented big bores, and there is no mistaking the result when you twist the loud handle. It just rears up and goes. A blistering eighth-mile time lets you know you’re on The Original TT Bike. The T’s stand for Tavern to Tavern. And a rider needs absolutely no class at all to do 90-mph quarter-miles with this beast.

Drop in for the usual teacup full (2.25 gal.) of gas required about every 80 miles, and gas station attendants will trip all over their hoses to get a better look at this magnificent thing that goes “rumpety-rump.” The XLCH styling—neolithic American—would put off a purist, but so do Superbees, Chargers, and Shelby GTs. It is awesome. Metal slab on metal slab, cut with a blunt chisel. Nothing seems to go with anything else. The psychology of fear and ambivalence is epitomized in an XLCH: both emotions arise in the presence of something not easily understood or comprehended. The pieces only fall into place when the bike is in motion. Loping easily up a boulevard, or charging up a piece of freeway, it looks, feels and sounds just right.

There is nothing overwhelmingly new on the Sportster of the 70s. Newest was the electric starter on the Sportster XLH tested by CYCLE WORLD last year. XLCH stylists have created an optional fiberglass seat/rear fender unit. If you like your Sportster the good old way, you don’t have to buy it. But we think it is rather racer-ly.

The factor that has most served to tame the Sportster’s legendary tendency to kick back or refuse to start at all is the substitution of battery and coil for the magneto to provide spark at low kick-over speed. The spark advance is now automatic, so that extra chore of retarding it for the start, by turning the left twist grip (and subsequent pain in the right foot if you forgot), is unnecessary. Of course, that eliminates the fun that could be had in bombarding other boulevardiers with voluntary retarded-spark backfires, but perhaps progress is to be welcomed in this case, with the heat being on, you know. And starting is definitely easy.

The source of the XLCH’s perennial funkiness is that engine, which, like the backward curving handlebars, has a lineage going back to the 61s of board track days. The racing KR has it, the gigantic FLH has it and the Sportster has it—a hefty, galloping sound at low speed, raising to an irresistible machine gun stagger at high rpm.

The overwhelming music is caused by the V-twin configuration, in which the cylinders mount on the crankcase 45 degrees apart. The front cylinder fires, and, 315 degrees of crankshaft rotation later, the rear cylinder fires. Yet another 405 degrees later, during which time the scavenging/intake piston strokes occur, we’re back to the front cylinder for yet another round. This somewhat lop-sided firing sequence is hardly conducive to smoothness, but is necessary if the two pistons are to be allowed to run in-line on a common crankshaft, while keeping the engine in the relatively compact V configuration. What is lost on the firing line is gained in the balancing aspect in that the firing impulses are centered on the crankshaft, avoiding the off-center flexing, with resultant vibration, characteristic of the vertical Twin design. The V-Twin, in effect, is two Singles tied together, the second cylinder helping to smooth the “bang” of the first one. Some of the imbalance problems of the Single are present in the V-Twin, but these relate primarily to high rpm operation, for which the big bore V-Twin was never conceived in the first place.

At any rate, the lope present in the Harley engine is much akin to that of another famous loper, the automotive V-8, which never set records for theoretical or practical smoothness, but is the most ubiquitous and popular engine design in America today. The V-8 feel is substantial, solid, emotionally moving. These adjectives apply equally to the big Harley V-Twin.

To bring the connecting rods together on the built-up crankshaft involves the use of male and female rods. On a common crankpin, set between two flywheels, the front rod slips inside the rear rod, which is forked at the big end. The connecting rods run on roller bearings as do both ends of the crankshaft. The drive side of the crank is carried on a hefty pair of automotive sized tapered Timken bearings. Plain bushings are used for the rod small ends, as well as for the rocker arms. The four cam gears (one for each valve), which operate the overhead valves through roller tappets, pushrods and rocker arms, run on needle bearings.

While on the subject of breathing, it is worth noting that Sportster heads underwent a substantial improvement in early 1969, as the result of a flow testing program conducted by the factory. The intake port contour, in particular, was changed and is now much straighter.

The alloy pistons incorporate a unique Harley feature—an internal cast-in steel expander, which prevents slap, and/or loss of compression. When the pin boss sides of the piston expand, the expander, set vertically to the wrist pin axis, stops the thinner sides of the piston from moving inward.

Shaped in a high, blunt wedge, the sides of which leave room for the valves, the piston delivers a 9:1 compression ratio. It has three rings, two chrome-plated compression rings and a slotted, cast-iron oil control ring.

The Tillotson carburetor, which single-handedly feeds both cylinders, has also benefited from flow testing in the last few years. It can be a cantankerous beast to get functioning properly, and, in spite of the fact that it has adjustable low, intermediate and high speed jets, the task should be left to a qualified mechanic. Once in good fettle, it works beautifully, and the automotive diaphragm feature, which provides an extra squirt of raw fuel when the throttle is opened quickiy, provides instantaneous and positive acceleration. The rider should beware of a few things: i.e., indiscriminate fiddling with the jet adjustments when something else (usually) is at fault with engine tune, cranking the throttle too much during the starting procedure (which causes quick blueing of exhaust pipes), and leaving the fuel taps open when the engine is stopped (which may cause gasoline to drain into the cylinders if the diaphragm comes to rest in the wrong position).

Lubrication is accomplished by a double feed/scavenge pump housed in one pump body. Oil is force-fed to lower connecting rod bearings, timing gears and bushing, generator drive gear, rocker arm bearings, valve stems, valve springs, pushrods and tappets. Spray thrown off by the crankshaft and connecting rods, and oil draining from the rocker boxes through to two holes at the base of each cylinder, lubricates the cylinder walls, pistons, piston pins and main bearings. The scavenging section of the oil pump provides lubrication to the rear chain as well as returning oil to the separate supply tank.

The Sportster owner should keep a close check on his oil supply, incidentally, as normal oil mileage varies from 250 to 500 miles a quart, depending on how the bike is driven and its state of tune. A good safety feature is the automotive style oil pressure light found on the panel over the headlight; when things are working properly, the light should go out at any speed above idle.

The Sportster’s four-speed transmission rates among the smoothest and most effort-free to be found in the big-bore category. It makes no grinding or clunking sounds during gear changes, and requires neither forcing of the foot lever nor a delay in timing when shifting at high rpm. In spite of this fact, the Harley service people have run into trouble from some of their heavy-footed clients, and have seen fit to eliminate the spline connection between the gear lever and actuation shaft in favor of a smooth joint, which will slip if it encounters resistance. The transmission is of conventional constant mesh mainshaft/countershaft design, but the liberal use of ball, roller and needle bearings on friction surfaces contributes greatly to its efficient, light operation.

Ratios in the XLCH befit the bike’s short-haul demeanor; overall gearing is shorter than the electric starting XLH. Result is a good set-up for the eighth mile, corresponding to aforementioned “TT” runs, but rather inconvenient spacing for the quarter mile. A knowledgeable XLCH owner interested

in improving his time at the drags (or perhaps changing the gear spread to pull a higher top cog for more relaxed cruising) will take advantage of a number of internal ratios interchangeable from the racing KR. In addition, alternate countershaft sprockets, ranging from 17 to 25 teeth, are available.

The clutch seems indestructable, judging by its unfaltering performance during repeated drag strip runs. The lever requires surprisingly moderate pressure, and the gradation between free and fully engaged is both long and even. It is of the dry, multiplate variety (seven metal drive plates and seven friction plates), with pressure controlled by six clutch springs. Located in the primary case, it picks up its power from the engine sprocket by means of a triplex chain.

Much verbiage has been spilled pro and con about the Sportster’s handling. Of course, it is the most nimble of Harley’s big-bore street machines, and was created (in the K days) in an attempt to attract riders to the H-D fold who might otherwise be put off by the blimpish riding qualities of the 74s.

Keeping in mind that the XLCH is no lightweight at 495 lb., it handles rather well, as long as the rider doesn’t attempt to “stuff it” through the turns. The steering is somewhat neutral with understeer being more prominent at high speeds. The understeer and the long wheelbase will aid the average rider in staying out of trouble, although it will tend to make him exit wide if he enters a bend too hot or runs too narrow an angle before the apex.

Two basic factors will tend to inhibit confidence in all-out riding of bends, these being the high eg created by the long-stroke V design (not to mention the iron barrels), and the short pivot on which the swinging arm has to operate. The understeer compensates well for the high eg and works against the potential tendency of all that top weight to fall down when the bike-is leaned into the turn. The short swinging arm pivot, and the not-too-sturdy looking swinging arms will lend themselves to side waggle under banzai conditions, but will be adequate for moderate doses of play racing.

The front fork damping hides the Sportster’s weight well, and lunging could be induced only under extreme conditions. The angle of the rear shocks, as Harley personnel will readily admit, is more appropriate to the easy placement of saddlebags than anything else. Canted forward as they are, the travel of the plungers is less, per given deflection of the swinging arm, than it would be if the units were more vertical. Hence rear damping is less than it might be. But, to put things in perspective, nobody buys a Sportster to go road racing.

Braking is surprisingly good, with relatively little fade. Stopping distances from 30 and 60 mph are on a par with any production big-bore manufactured today.

One improvement in rolling gear, standard on the Sportster, is the “safety rim” wheel, the same as used on California Highway Patrol Harleys. Similar to an automobile wheel, the rim is stepped in an L shape to provide a firm anchor for the tire bead, serving to hold the tire on the wheel when a blowout occurs. Goodyear tires of special design to accommodate the new rim pattern are fitted to the Sportster.

Also of interest is the new externally mounted mini-battery, which translated from Harley language turns out to be a normal-to-large sized motorcycle battery. The sides are transparent, so the fluid level may be conveniently checked against the reference marks without removing caps or battery box covers.

The general finish on the XLCH has few equals in the motorcycle industry, as befits a machine costing as much as a small sedan. The instruments are attractive and easy to read, although the speedometer, 10-plus mph optimistic, stretches the credibility gap to an extreme.

All in all, good friend Charlie does pretty much what is claimed for him. He wasn’t meant to be much of a tourer; even with newer, bigger mufflers his heady rumblings wear on the endurance after several hours of riding. Fortunately, for trip takers, an optional 4-gal. gas tank will render him much more practical for the job than he is now.

In a way, though, it would be a shame to eschew that funny little tank which is part of Charlie’s charm. Charlie is in a league by himself—a stud machine for studs. He doesn’t make much pretense about being functional. Quite simply, he’s a fun guy to have around. \Q\

HARLEY-DAVIDSON

XLCH

$1767

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

November 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

November 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1969 -

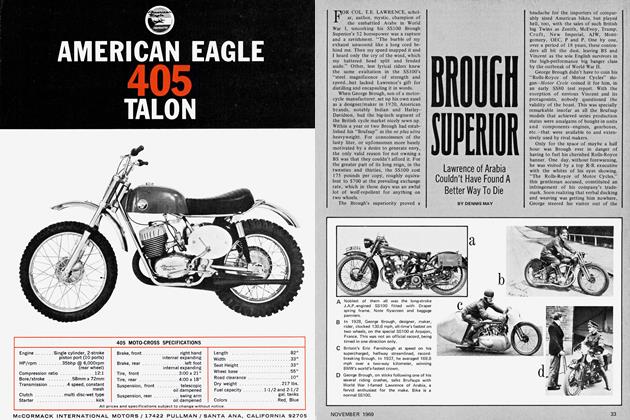

Features

FeaturesBrough Superior

November 1969 By Dennis May -

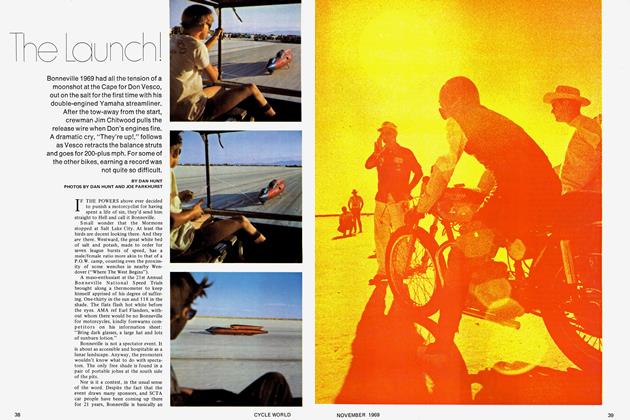

Special Feature

Special FeatureThe Launch!

November 1969 By Dan Hunt