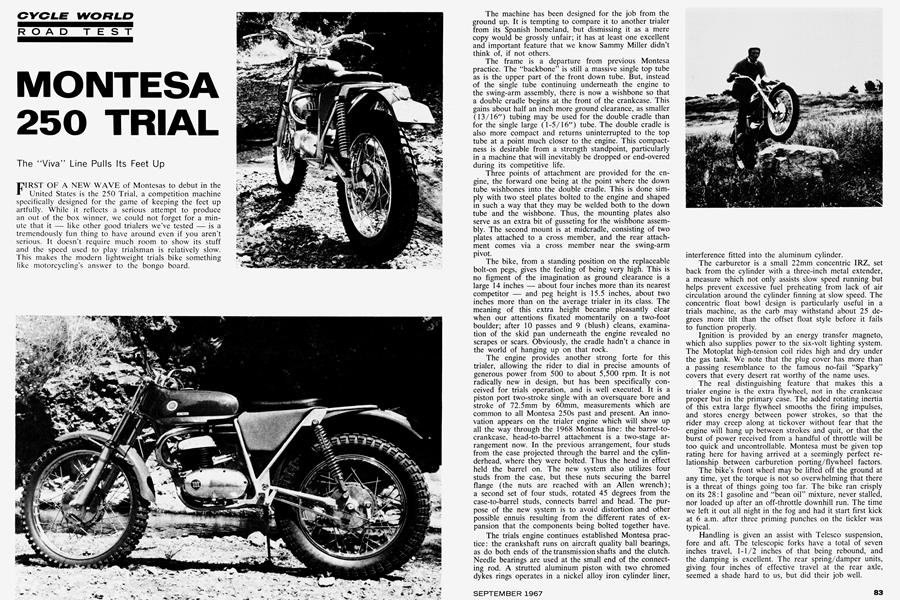

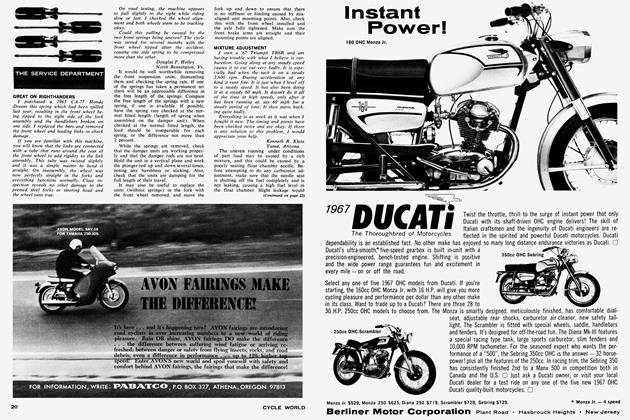

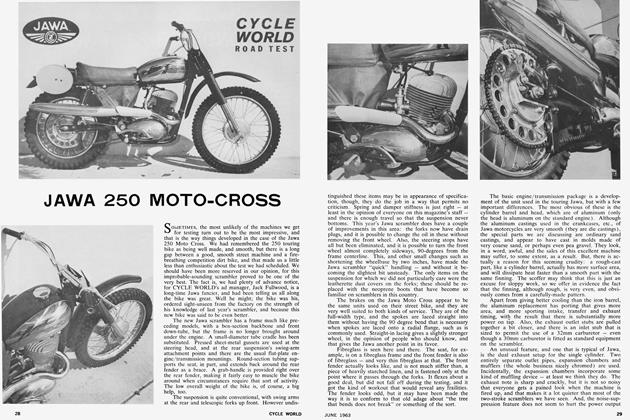

MONTESA 250 TRIAL

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The "Viva" Line Pulls Its Feet Up

FIRST OF A NEW WAVE of Montesas to debut in the United States is the 250 Trial, a competition machine specifically designed for the game of keeping the feet up artfully. While it reflects a serious attempt to produce an out of the box winner, we could not forget for a minute that it — like other good trialers we've tested — is a tremendously fun thing to have around even if you aren't serious. It doesn't require much room to show its stuff and the speed used to play trialsman is relatively slow. This makes the modern lightweight trials bike something like motorcycling's answer to the bongo board.

The machine has been designed for the job from the ground up. It is tempting to compare it to another trialer from its Spanish homeland, but dismissing it as a mere copy would be grossly unfair; it has at least one excellent and important feature that we know Sammy Miller didn't think of, if not others.

The frame is a departure from previous Montesa practice. The "backbone" is still a massive single top tube as is the upper part of the front down tube. But, instead of the single tube continuing underneath the engine to the swing-arm assembly, there is now a wishbone so that a double cradle begins at the front of the crankcase. This gains about half an inch more ground clearance, as smaller (13/16") tubing may be used for the double cradle than for the single large (1-5/16") tube. The double cradle is also more compact and returns uninterrupted to the top tube at a point much closer to the engine. This compactness is desirable from a strength standpoint, particularly in a machine that will inevitably be dropped or end-overed during its competitive life.

Three points of attachment are provided for the engine, the forward one being at the point where the down tube wishbones into the double cradle. This is done simply with two steel plates bolted to the engine and shaped in such a way that they may be welded both to the down tube and the wishbone. Thus, the mounting plates also serve as an extra bit of gusseting for the wishbone assembly. The second mount is at midcradle, consisting of two plates attached to a cross member, and the rear attachment comes via a cross member near the swing-arm pivot.

The bike, from a standing position on the replaceable bolt-on pegs, gives the feeling of being very high. This is no figment of the imagination as ground clearance is a large 14 inches — about four inches more than its nearest competitor — and peg height is 15.5 inches, about two inches more than on the average trialer in its class. The meaning of this extra height became pleasantly clear when our attentions fixated momentarily on a two-foot boulder; after 10 passes and 9 (blush) cleans, examination of the skid pan underneath the engine revealed no scrapes or scars. Obviously, the cradle hadn't a chance in the world of hanging up on that rock.

The engine provides another strong forte for this trialer, allowing the rider to dial in precise amounts of generous power from 500 to about 5,500 rpm. It is not radically new in design, but has been specifically conceived for trials operation, and is well executed. It is a piston port two-stroke single with an oversquare bore and stroke of 72.5mm by 60mm, measurements which are common to all Montesa 250s past and present. An innovation appears on the trialer engine which will show up all the way through the 1968 Montesa line: the barrel-tocrankcase, head-to-barrel attachment is a two-stage arrangement now. In the previous arrangement, four studs from the case projected through the barrel and the cylinderhead, where they were bolted. Thus the head in effect held the barrel on. The new system also utilizes four studs from the case, but these nuts securing the barrel flange (the nuts are reached with an Allen wrench); a second set of four studs, rotated 45 degrees from the case-to-barrel studs, connects barrel and head. The purpose of the new system is to avoid distortion and other possible ennuis resulting from the different rates of expansion that the components being bolted together have.

The trials engine continues established Montesa practice: the crankshaft runs on aircraft quality ball bearings, as do both ends of the transmission shafts and the clutch. Needle bearings are used at the small end of the connecting rod. A strutted aluminum piston with two chromed dykes rings operates in a nickel alloy iron cylinder liner, interference fitted into the aluminum cylinder.

The carburetor is a small 22mm concentric IRZ, set back from the cylinder with a three-inch metal extender, a measure which not only assists slow speed running but helps prevent excessive fuel preheating from lack of air circulation around the cylinder finning at slow speed. The concentric float bowl design is particularly useful in a trials machine, as the carb may withstand about 25 degrees more tilt than the offset float style before it fails to function properly.

Ignition is provided by an energy transfer magneto, which also supplies power to the six-volt lighting system. The Motoplat high-tension coil rides high and dry under the gas tank. We note that the plug cover has more than a passing resemblance to the famous no-fail "Sparky" covers that every desert rat worthy of the name uses.

The real distinguishing feature that makes this a trialer engine is the extra flywheel, not in the crankcase proper but in the primary case. The added rotating inertia of this extra large flywheel smooths the firing impulses, and stores energy between power strokes, so that the rider may creep along at tickover without fear that the engine will hang up between strokes and quit, or that the burst of power received from a handful of throttle will be too quick and uncontrollable. Montesa must be given top rating here for having arrived at a seemingly perfect relationship between carburetion porting/flywheel factors.

The bike's front wheel may be lifted off the ground at any time, yet the torque is not so overwhelming that there is a threat of things going too far. The bike ran crisply on its 28:1 gasoline and "bean oil" mixture, never stalled, nor loaded up after an off-throttle downhill run. The time we left it out all night in the fog and had it start first kick at 6 a.m. after three priming punches on the tickler was typical.

Handling is given an assist with Telesco suspension, fore and aft. The telescopic forks have a total of seven inches travel, 1-1/2 inches of that being rebound, and the damping is excellent. The rear spring/damper units, giving four inches of effective travel at the rear axle, seemed a shade hard to us, but did their job well.

Just why on earth Montesa should elect to mount such a tread pattern up front (3.00 x 21 Pirelli motocross), or the 4.00-18 Firestone Motor Sports (resembling the Grasshopper) in the rear is beyond us. Both these patterns have a rounded profile, which, while quite effective in its proper place, is of questionable value on a trialer. Yes, a rounded profile keeps the same amount of tread on the ground no matter how the bike is leaned. But the experienced trials rider would argue that it is better to have a flat profile (such as the Dunlop Trials Universal) giving optimum tread contact straight up and down, then compensating for turns and off-camber situations with the appropriate inward body lean.

We have another complaint that has to do with the steering lock, which is not as much as it might be, and this seems to have happened only because the tres chic gasoline tank styling somehow got ahead of the priority of function. Fortunately, the amount of lock, necessary for making super-sharp turns where "faking it" with body lean won't do, may be increased a few degrees on each in simple fashion, using only a file or hacksaw and a bit of restraint. The control cables should be carefully rerouted so they aren't pinched between the fork stanchions and tank. And while you're at it, you can throw away the waffle pattern hand grips, which look like the real thing in rubber, but are really hard plastic and cut through a pair of gloves to dig into the rider's hands. We were at first inclined to raise our eyebrows at the smart-looking leather side pads which attach as a unit with the seat to the frame. After all, what was this, country-squire styling on a purist's machine? But after our first ride we were converts. They provided excellent non-slip grip for the calves of the leg — an extremely substantial "plus" in the control department. This clever piece of industrial design also serves to hide a good sized intake filter box and a long exhaust silencer, which brings the noise down to proportions not quite fit for in-town consumption but well enough so as not to provide selfharassment for the rider. If the bike is used in dry brush areas, the housing provides another service by making it almost impossible for direct exhaust gases to contact the foliage.

Gear spacing is according to the "modern'" pattern, with three closely spaced lower gears and then a walloping lurch to an overdrive fourth for between-section cruising at about 40 mph. To our tastes, third is too close to second, but, for the buyer who agrees with us, a change is easy to make from Montesa's existing assortment of gear ratios. First and second cogs seem just right. Placement of the gear shift lever is good, just forward enough so that it won't be hit accidentally by the toe. The shifting seemed stiff, but as there were other symptoms indicating the 13-plate all metal disc clutch wasn't freeing up completely, we would suspect this to be a matter of adjustment.

As for other bits and pieces, we liked the positioning of both the kick starter, which gives most effective starts from a standing position on the pegs, and the rear brake lever, which becomes a useful part of your body after a few moments on the bike. The bars, at 32 inches wide, are proper and well-positioned for a large person. The lights really do work. The side stand clanked against the swing-arm, but otherwise was effective and troublefree.

The welding is typically Spanish, which is to say that they make it look very difficult. In spite of this, the 250 Trial must be one of the most beautiful trialers in existence.

Taken as a whole, the machine is a success and, for the U.S. buyer, will require little changing after the purchase is made. ■

MONTESA

250 TRIALS

SPECIFICATIONS