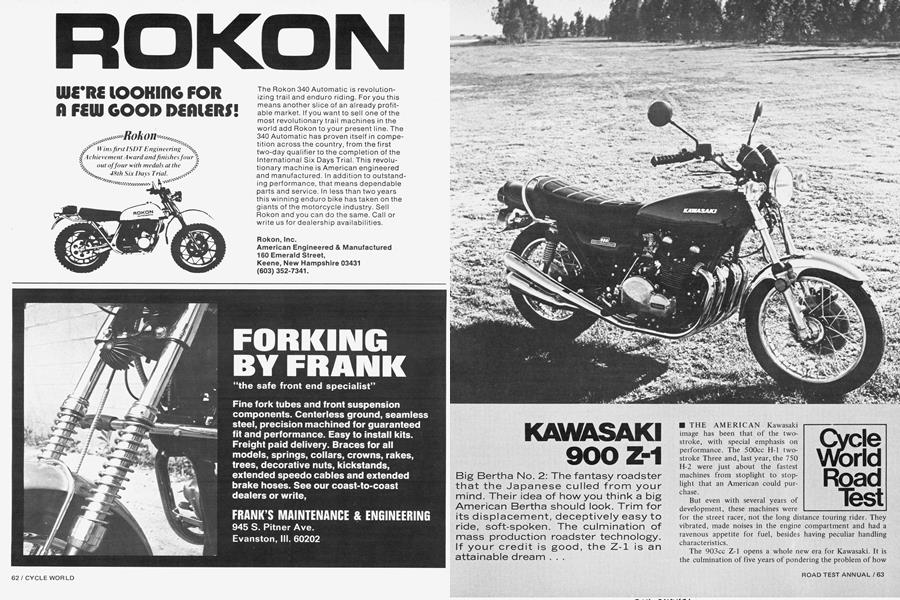

KAWASAKI 900 Z-1

Cycle World Road Test

Big Bertha No. 2: The fantasy roadster that the Japanese culled from your mind. Their idea of how you think a big American Bertha should look. Trim for its displacement, deceptively easy to ride, soft-spoken. The culmination of mass production roadster technology. If your credit is good, the Z-1 is an attainable dream . . .

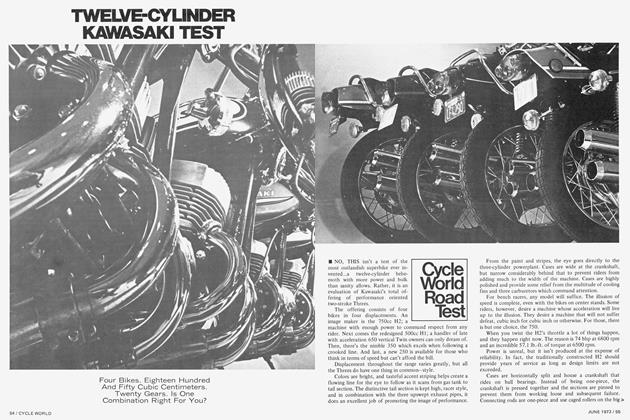

THE AMERICAN Kawasaki image has been that of the two-stroke, with special emphasis on performance. The 500cc H-1 two-stroke Three and, last year, the 750 H-2 were just about the fastest machines from stoplight to stoplight that an American could purchase.

But even with several years of development, these machines were for the street racer, not the long distance touring rider. They vibrated, made noises in the engine compartment and had a ravenous appetite for fuel, besides having peculiar handling characteristics.

The 903cc Z-1 opens a whole new era for Kawasaki. It is the culmination of five years of pondering the problem of how to have your cake and eat it, too, or combining sheer performance with comfort. This Kawasaki gives away nothing in either department.

It is one of the two or three quickest road bikes in production. Yet it is luxuriously big, and politely sibilant. It goes fast in a slow way, covering ground in great bites. The Z-l is one of those shockingly understated GT machines, the kind on which you can look down at the speedometer and discover, “My God, I’m doing 90, I’d better shut down.”

While the Z-l is eclectic, a summation of everything we know about roadster technology, it has no parallel at present. Within the limitations of its weight, it can handle most any accelerating, turning or stopping situation that an expert rider can deal it. Yet the less rabid touring man can find his proper place on the Z-l, too, and not be obliged to wrestle with hair-raising tuning.

It runs on regular gas. And it also runs well with a regular rider.

At first glance the Kawasaki Z-l looks much like the Honda CB750. A transverse Four is not an unusual sight these days, but an investigation of the engine/transmission unit reveals differences from other transverse Fours which are noteworthy and almost unique. The most significant departure from common design practice is the adoption of double overhead camshafts, driven by a chain from between the middle cylinders’ crankshaft area. A twin cam arrangement like this permits the cam lobes to operate directly on caps on the valve stem ends, obviating the need for rocker arms which can flex at high rpm, cause the valve timing to alter slightly, and encourage premature valve float.

The only drawback of such a cam system is the necessity of substituting valve top cups of differing thicknesses when it becomes necessary to adjust valve clearance. Because of the fewer number of moving parts in the valve area, valve adjustments should not be necessary very often, in spite of the high engine operating speeds permitted by such a design. Engine red line rpm is 9000, which is strange when you consider that the cam timing is very mild indeed.

With one of the design criteria being low emissions, the Z-l employs flat top pistons with three rings which give a compression ratio of 8.5:1. During extensive testing it was found that the Z-l would run without detonating even on the poorest quality regular gas. Since the exhaust valve seats are made of a special sintered material, premature wear will not occur with low-lead and no-lead gasolines. Also helping in the battle against emissions is an air/oil separator on top of the crankcase in the transmission area. This device allows blow-by gases from the crankcase to be separated from any oil and then be directed into the bottom of the rubber plenum which leads from the carburetor inlets to the air filter. By reburning these crankcase vapors, the output of hydrocarbons is lowered by nearly 40 percent.

Four 28mm Mikuni carburetors attach to four smoothly contoured inlet stubs on the cylinder head. A push-pull throttle cable arrangement like the Honda CB500 Four ensures positive closing of the carburetors’ slides and is set to require only moderate effort by the rider’s right hand to keep the throttle open to the desired setting. Also, with an arrangement like this the carburetors are more easily kept synchronized.

The crankshaft looks more like it came out of a racing automobile than from a touring motorcycle. One-piece connecting rods ride on caged needle bearings and the crankshaft is a pressed together unit comprising nine pieces. Almost all other four-cylinder non-racing engines have plain babbit bearings at the bottom of each connecting rod, and although this type of bearing develops more heat, it is capable of withstanding greater low-speed loadings. Due to the Z-l’s intended use, the lower friction (and lower heat) needle bearing setup was chosen which allows high revs with safety due to the slightly lighter weight of the one-piece rod. Another plus is that such a rod is usually narrower in cross section than a two-piece rod, keeping down unwanted engine width.

Because less heat is developed in the Kawasaki’s crankshaft area, a gear-type oil pump, driven from a gear on the crankshaft between the number one and number two cylinder, feeds oil at low pressure (in the neighborhood of 6 lb./sq. in.) through the filter to the engine through three passages. One passage leads to the crankshaft main bearings and crank pins and excess oil lubricates the pistons, cylinder walls and other parts by splash. The second passage divides into two passages, travels to the top of the engine, and lubricates the camshafts’ plain bearings and the valve gear. The third passage directs oil to the transmission gears and shafts.

The Z-l oil supply is carried totally in the engine’s sump, unlike the CB750 Honda which has a dry-sump oil system with a separate oil tank. Kawasaki has managed to contain more than 7 pt. of oil in the engine without raising the already tall power unit, and without having to use external oil lines. A convenient sight glass is provided in the side of the clutch cover for checking the oil level.

Power from the crankshaft to the clutch is transmitted by spur gears, one of which is located on the crankshaft, inboard of the number four cylinder flywheel. This is another effort to keep the engine narrow and although a gear drive is inherently noisier than a chain, there are no noises coming from that area of the Z-l.

The clutch is an enormous 8-plate unit which will take much abuse and slipping without giving any trouble. Transmission gears are robust and both the mainshaft and the layshaft feature needle and ball bearings to support them. Shifting is practically effortless and the shift lever travel is decidedly short and crisp. However, the end of the shift lever is a little too close to the bulge on the left hand end of the engine, in which the alternator is housed, for folks with big feet. It was occasionally necessary to move the left foot farther back on the footpeg to keep from touching the bulge.

The right hand end of the engine is narrow, because the only items inside that cover are the two sets of points and the automatic spark advance mechanism. Electric starting seems to be the norm these days and the Z-l has one of the best executed units we’ve seen. The starter motor rides on the left hand side of the engine just above the gearbox and transmits its power through a reduction gear to the crankshaft.

Anticipating short rear chain life from a machine with so much torque and high speed potential, the engineers at Kawasaki wisely saw fit to develop a larger rear chain (3/4-in. pitch) and provide a supplemental positive rear chain oiler with its own oil tank. This pump is located at the left end of the gearbox casing and delivers oil at the rate of 3cc per hour at normal highway speeds.

The rear chain is a one-piece unit. Special stops allow the rear wheel to be moved forward enough to get it off to fix a flat tire without taking the chain apart. Still, Kawasaki recommends hand lubrication of the chain every few hundred miles or after riding through rain or washing the machine. Rear chain life will most definitely be a problem if the machine isn’t ridden conservatively and the rear chain isn’t maintained religiously. And rear tire life can’t be expected to be long either.

But spirited riding is just what the Z-l thrives on. Even though cornering power is somewhat limited by the center stand on the left hand, the large machine can be swooped through a series of S-bends with complete confidence if the rear shock absorber springs are adjusted up a notch or two from their softest position. The personnel at Kawasaki Motors Co. had adjusted the rear shocks to their third (middle) position before we received the Z-l for test, and we were curious to see why. With the springs on their lowest (softest) position the ride was more comfortable, but the rear end would “wallow” in sharp or high speed turns. Preferring stability to slightly better comfort, we returned the springs to the middle adjustment.

Front suspension is nearly ideal with more than adequate travel and superb action. At no time did we feel that the front forks could be improved upon for general road riding, although a racing application would call for slightly stiffer springing.

Much of the Z-l’s excellent handling must be attributed to the frame. It is a double cradle affair with large (1.26-in.) diameter tubing used for the main section. Liberal gusseting at the steering head and, just as important, at the swinging arm pivot point, help keep the heavy machine on an even keel. The swinging arm is a massive (1.61-in. diameter) affair and its pivot bolt has a safety lock nut on the end to prevent its loosening. As with most Japanese frames, the welding looks a little crude here and there, but penetration appears to be excellent.

Braking is an extremely important aspect of any high performance motorcycle and the Z-l again came through with flying colors. The 11.65-in. diameter front disc brake, which provides most of the stopping power, took stop after stop without a trace of fade. It takes a really firm grip on the front brake lever to slide the front wheel on dry pavement, but we managed to skid the wheel a few times during our 60-0 mph deceleration tests. As a point of interest, the right hand fork leg has disc brake caliper mounting lugs already cast on, so it wouldn’t be too difficult to mount another disc on the right side. Even though we feel the single disc is adequate, the addition of another disc would reduce the lever pressure necessary and give a power brake feel.

The rear brake is a healthy 7.9x1.4-in. unit in a massive cast aluminum hub which also contains rubber blocks to separate the hub from the rear sprocket. This practice, often called a cush drive, reduces the strain on the fear chain and the transmission components during ultra low rpm running and during gear shifting.

Styling of the Z-l is very assertive, in a subtle way. From the front chromed, slightly valanced, fender up the forks to the neatly arranged instrument cluster the lines flow well and blend into a businesslike combination. The instrument panel and the rear view mirrors are finished in flat black to obviate glare from the sun getting into the rider’s eyes. All controls are within easy reach of the rider’s hands and work perfectly. Even the ignition key is located where it should be: right in the center of the instrument panel instead of under the gas tank or the seat.

The gas tank has a pleasant teardrop shape which belies its 4.7-gal. capacity. A wide, soft seat gives ample support to the rider’s backside for long stretches in the saddle. The rear portion of the seat is also wide, but is firmer than the front. Our pillion passengers didn’t complain, however, and more than one commented on the lack of vibration coming up through the rear footpegs. The seat also locks down, keeping the tools and personal belongings the rider might carry in the clever map case in the rear of the seat safe.

Typically Kawasaki, the rear seat extension looks a little odd, but serves as a mounting point for the taillight.

Rakishly upswept mufflers that emit the low sound level of 84dbA and the stylish plastic side covers complete the sleek appearance of the Z-l, one of the most desirable machines to come from Japan in a long time.

Riding the Z-l is a thrill that can hardly be described. Extremely cold-blooded, the Z-l must be warmed up for a couple of minutes before it can be ridden without the choke. Once warm, the idle speed settles down to 1200 rpm and soft, smooth whirring sounds come from the engine. Withdraw the clutch lever, snick the gear lever down into low gear and prepare to experience the smoothest trip ever. Due to its mild state of tune, the Z-l can be made to pull from 1000 rpm up without hesitation or bucking. Good power comes on as low as 2500 rpm and doesn’t fall off until well past 8500 rpm. This is truly one of the most flexible machines we’ve ever sampled.

Our day at the drag strip proved to be the highlight of the week. With such power, the Z-l proved to be a real challenge to get off the line. Too many revs and dropping the clutch provided so much wheelspin that the machine nearly swapped ends before the throttle could be shut off. Insufficient throttle would cause the Z-l to bog down slightly, but it would still pull away from the start smartly enough to turn quarter-mile times in the high 12s at over 100 mph.

With much practice we were able to turn our best time in 12.61 sec. with a terminal speed of 105.63 mph. In more than a dozen runs down the strip the times never varied more than three-tenths of a second or three mph! Nor was a single clutch adjustment required all day.

Getting a top speed reading was not as difficult, but was hardly fair to the machine: we only had a fraction over 1/2 mile in which to accelerate up to the top speed we recorded with our radar of 120 mph. With another 1/2 mile we feel that another five or six mph could have been obtained. It’s a shame that people must go to Nevada to ride the Z-l to its limits legally!

Overall finish of the Z-l is first-rate. Electrical components are without fault except for the meek sound the horn emits, and the overall aura of the machine is scintillating. It won’t replace the Harley-Davidson Sportster as the ultimate stud bike, or the BMW as the ultimate touring machine, but it has created a special niche in motorcycling into which many riders will find their way.

KAWASAKI 900 Z-1

$1895

View Full Issue

View Full Issue